An Introduction to Consciousness

consciousness

MIND-ALTERING MEDICINE

An Introduction to Consciousness

MIND-ALTERING MEDICINE

Robert Julien, M.D., did not choose a typical 9-to-5 job. His profession involves paralyzing people, interfering with their memory formation, and numbing their senses—but only temporarily. Dr. Julien is an anesthesiologist, a medical doctor whose primary responsibility is to monitor a patient’s vital functions (for example, respiration and pulse) and manage pain before, during, and after surgery. With the help of powerful drugs that manipulate the nervous system, Dr. Julien has eased the pain and anxiety of over 30,000 patients undergoing procedures that otherwise would likely have been very unpleasant.

In ancient times, people may have sought pain relief by dipping their wounds in cold rivers and streams. They concocted mixtures of crushed roots, barks, herbs, fruits, and flowers to ease pain and induce sleep in surgical patients (Keys, 1945). Many of the plant chemicals discovered by these early peoples are still given to patients today, although in slightly different forms. Opium was used by the ancient Egyptians (El Ansary, Steigerwald, & Esser, 2003), and its chemical relatives are used by modern-day physicians and hospitals all over the world (for example, morphine for pain relief and codeine for cough suppression).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

after reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- LO 1 Define consciousness.

- LO 2 Explain how automatic processing relates to consciousness.

- LO 3 Describe how we narrow our focus on specific stimuli to attend to them.

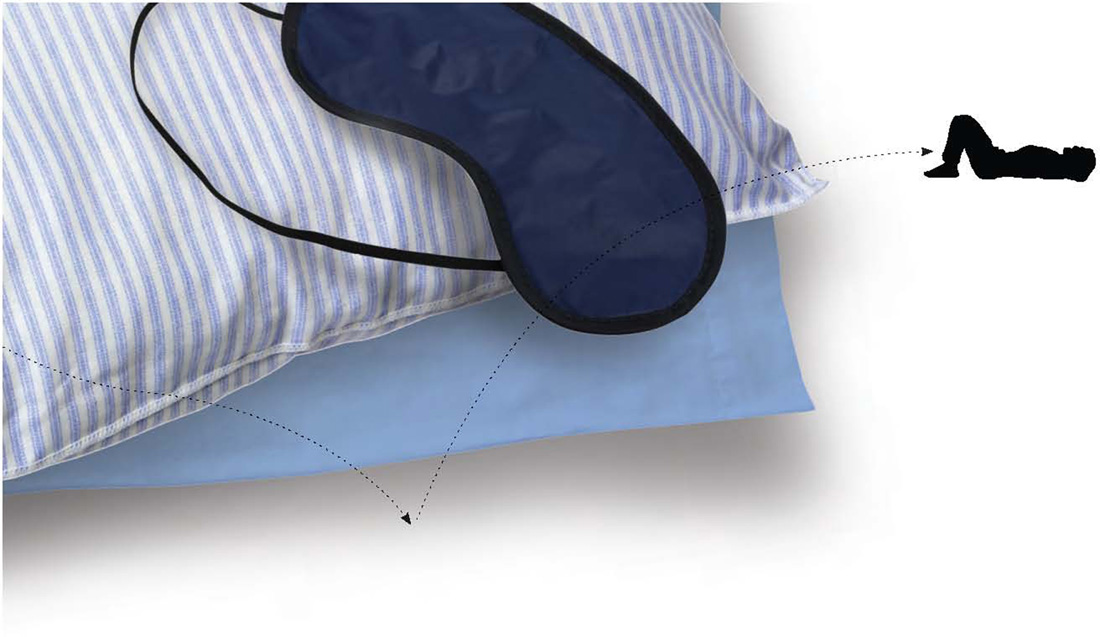

- LO 4 Identify how circadian rhythm relates to sleep.

- LO 5 Summarize the stages of sleep.

- LO 6 Recognize various sleep disorders and their symptoms.

- LO 7 Summarize the theories of why we dream.

- LO 8 Define psychoactive drugs.

- LO 9 Identify several depressants and stimulants and know their effects.

- LO 10 Discuss some of the hallucinogens.

- LO 11 Explain how physiological and psychological dependence differ.

- LO 12 Describe hypnosis and explain how it works.

Nevertheless, anesthesia’s routine use during surgery did not occur for centuries. Before the mid-1800s, surgery was so painful, patients writhed and screamed on operating tables, sometimes held down by four or five people (Bynum, 2007). During the Mexican-American War, a band would play when Mexican soldiers had their limbs amputated so the men’s cries would not be heard by others (Aldrete, Marron, & Wright, 1984). The only anesthetic available may have been whiskey, wine, or a firm blow to the head, that is, patients were literally knocked out. Fortunately, the science of anesthesia has come a long way. It is now possible to have a tooth extracted or a mole removed without a twinge of discomfort. A patient undergoing open heart surgery can lie peacefully as surgeons pry open his chest and poke around with their instruments, then leave the hospital with no memory of the actual surgery. But anesthesia is a curious thing. Drugs used to ease pain and anxiety also influence sensations, perceptions, and one’s awareness of self and the environment: They can dramatically alter “conscious” experiences.

Note: Unless otherwise specified, quotations attributed to Dr. Robert Julien and Matt Utesch are personal communications.

What is Consciousness?

LO 1 Define consciousness.

People usually think of consciousness as the state of being awake and unconsciousness as what happens when you are asleep, but as you will learn in this chapter, consciousness is a concept that can be difficult to pinpoint. Although some psychologists disagree about its precise definition, G. William Farthing offers a good starting point: Consciousness is “the subjective state of being currently aware of something either within oneself or outside of oneself” (1992, p. 6). Consciousness is best defined as the state of being aware of oneself, one’s thoughts, and/or the environment. According to this definition of subjective awareness, one can be asleep and still be aware (Farthing, 1992). Consider this example: You are dreaming about a siren blaring and you wake up to discover it is your alarm clock; you were clearly asleep but aware at the same time, as the sound registered within your brain. This ability to register a sound while asleep is very important in the production of not only alarm clocks but also smoke detectors and fire alarms. Human factors researchers have conducted numerous studies to determine the types of sounds most likely to arouse a sleeping person, as well as individual differences (for example, age, gender, sleep deprivation, hearing ability, and sleep stage) that affect whether a person will register and/or wake up to a sound (Bruck & Ball, 2007). This ability to remain aware of our environment even while sleeping has served us well, allowing our ancestors to be vigilant about dangers day and night.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we considered the subfield of human factors engineering. Just as we can study sensation and perception as they relate to machines and equipment, human factors engineers must be aware of issues related to consciousness and the design of machines.

Consider this story: Several years ago, Dr. Julien had a patient who didn’t want to have general anesthesia during her hysterectomy, an operation to remove the uterus. Anesthesiologists typically put patients “to sleep” for hysterectomies, but Dr. Julien agreed to honor the patient’s unusual request. He gave her a drug called Versed (midazolam) to help her relax, but not enough to knock her out. (Versed belongs to a class of calming drugs called depressants, which you will learn about later.) The woman seemed to be wide awake throughout the two-and-a-half hour procedure, chatting with doctors and nurses and even requesting that certain music be played in the operating room (much to the dismay of the surgical team).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced the evolutionary perspective. The adaptive trait to remain aware even while asleep has evolved through natural selection, allowing our ancestors to defend against predators and other dangerous situations.

At 11:00 p.m. that night, Dr. Julien received a phone call from a nurse indicating that the patient was furious because he had used general anesthesia during the operation. Apparently, she could not remember any of the experience. The drug Dr. Julien had used to help the patient relax can also cause memory loss for events experienced while under its influence. Unable to remember the surgery, the patient logically assumed she had been given general anesthesia. “I went to the hospital at midnight to explain to the patient that I had honored her request and that she had been wide awake during the procedure but was unable to form memory proteins because the Versed had blocked their formation,” Dr. Julien explained. In other words, the Versed had interfered with the production of a protein needed for memory creation. “To this day, I’m not sure she ever accepted my explanation or forgave me for taking away any memory of the procedure” (Julien & DiCecco, 2010, p. 11).

Consciousness and Memory

Would you say Dr. Julien’s patient was conscious during the operation? If consciousness is a “subjective state of being currently aware” (Farthing, 1992, p. 6), then it would appear she was conscious during the surgery. She was alert and talking, yet her awareness of the event vanished within hours, so was she conscious after all? Let’s not confuse consciousness with memory. It appears she was conscious at the time but later had no memory of the event. As Dr. Julien explained to her, a failure occurred in the process involved in memory formation, for example, in the encoding or storage of the event (Chapter 6).

Millions of Americans suffer from memory problems similar to that experienced by Dr. Julien’s patient. They are aware, alert, and able to have meaningful conversations, yet they cannot form new memories (they may suffer from Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia; Chapter 6). Then there are those who cannot form memories because they are taking consciousness-altering drugs. In very rare cases, people taking certain types of prescription sleeping pills have been known to “sleep-drive” or get behind the wheel in a trancelike state (Dolder & Nelson, 2008; Southworth, Kortepeter, & Hughes, 2008; Zammit, 2009). If such a person causes a fatal accident while in this sort of state, is she to blame? Keep this question in mind as we delve the depths of consciousness in the pages to come.

Studying Consciousness

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the contributions of these early psychologists. Wundt founded the first psychology laboratory, edited the first psychological journal, and used experimentation to measure psychological processes. Titchener was particularly interested in examining consciousness and the “atoms” of the mind.

The field of psychology began with the study of consciousness. Wilhelm Wundt and his disciple Edward Titchener founded psychology as a science based on research that examined consciousness and its contents. Another early psychologist, William James, was also interested in studying consciousness. According to James, consciousness can be thought of as a “stream” that provides a sense of day-to-day continuity (James, 1890/1983). Think about how this “river” of thoughts is constantly rushing through your head. An e-mail from an old friend appears in your inbox, jogging your memory of the birthday party she threw last month, and that reminds you that tomorrow is your mother’s birthday (better not forget that one), and you need to swing by the mall after class to pick up a gift for her. You notice your shoe is untied. You think about dinner last night, school starting tomorrow, your utility bill sitting on the counter; all of these thoughts might cross your mind within a matter of seconds. Thoughts interweave and overtake each other like currents of flowing water; sometimes they are connected by topic, emotion, events, but other times they seem to not be connected by anything other than your stream of consciousness.

Although psychology started with the very introspective study of consciousness, American psychologists John Watson, B. F. Skinner, and other behaviorists insisted that psychology as a science should only study observable behavior. This attitude persisted until the 1950s and 1960s, when psychology underwent a revolution of sorts. Researchers began to direct their focus back on the unseen mechanisms of the mind. Cognitive psychology, the scientific study of conscious experiences such as thinking, problem solv ing, and language, emerged as a major subfield. Today, understanding consciousness is an important goal of psychology, and many believe science can be used to further investigate its mysteries.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we presented the concept of objective reports, which are free of opinions, beliefs, expectations, and values. Here, we note that descriptions of consciousness are more subjective in nature, and do not lend themselves to objective reporting.

Although advanced technology for studying brain processes and functions has added to our growing knowledge, there are several barriers to studying consciousness. One is that consciousness is subjective, pertaining only to the individual who experiences it. Because of this, it is impossible to objectively study another’s conscious experience (Blackmore, 2005; Farthing, 1992). To make matters more complicated, consciousness is constantly changing; there is great variety in the conscious experiences within a person from moment-to-moment. Right now you are concentrating on these words, but in a few seconds you might be thinking of something else or slip into light sleep. In spite of these challenges, researchers around the world are inching closer to understanding consciousness by studying it from many perspectives.

Wrap Your Mind Around This

How exactly do psychologists understand this concept we call “consciousness”? We must first agree on what topics are relevant to the study of consciousness. There are many elements of conscious experience, including desire, thought, language, sensation, perception, and knowledge of self—simply stated, any cognitive process is potentially a part of your conscious experience. Memory is definitely a key player, as conscious experiences usually involve the retrieval of memories. Let’s look at what this means, for example, when you go shopping on the Internet. Your ability to navigate from page to page hinges on your ability to recognize visual images (Is that the PayPal home page or my e-mail log-in?), language aptitude (for reading), and motor skills (for typing and clicking). As you scroll through a page, or click on a hyperlink, your mind might wander from what you are looking at onscreen to a variety of memories (such as which link you just clicked, the shoes you saw last week while shopping, and the homework you were supposed to be doing)—all of this is part of your consciousness, your stream of thought.

try this

Stop reading and listen. Do you hear background sounds you didn’t notice before—a soft breeze rustling through the curtains or a car passing by? You may not have picked up on these sounds, but your brain was keeping tabs. You are constantly monitoring all this activity whether you are aware of it or not.

Automatic Processing

LO 2 Explain how automatic processing relates to consciousness.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we introduced the concept of sensory adaptation, which is the tendency to become less sensitive to and less aware of constant stimuli after a period of time. This better prepares us to detect changes in the environment, which can signal important activities that require our attention. Here, we see how this can occur through automatic processing.

One of the important distinctions often made regarding consciousness is between cognitive activity that happens automatically (without effort, control, or awareness on our part) and cognitive processes that require us to focus our attention on sensory input (with effort, we choose what to attend to and we are aware of this focus). Our sensory systems absorb an enormous amount of information, and one of the major functions of the brain is to sift through that information, determining what is important and needs immediate attention, what can be ignored, and what can be processed and stored for later use if necessary. This automatic processing allows information to be collected and saved (at least temporarily) with little or no conscious effort (McCarthy & Skowronski, 2011; Schmidt-Daffy, 2011). If it weren’t for automatic processing, we would be overwhelmed with data. Just imagine assuming some of your brain’s behind-the-scenes responsibilities (for example, keeping track of your heart rate or filtering unimportant noises) while taking a psychology midterm exam.

Automatic processing can also refer to the involuntary cognitive activity guiding some of our behaviors. We are seemingly able to behave and act without focusing our attention. Behaviors seem to occur without intentional awareness, and without getting in the way of our other activities (Hassin, Bargh, & Zimerman, 2009). A few examples are in order here. Do you remember the last time you drove a car on a familiar route, daydreaming the entire time? Somehow you arrived at your destination without noticing much about your driving, the traffic, and so forth. Or have you ever found yourself listening to music while cleaning the kitchen, and then realizing you are almost finished cleaning up without once being aware that you had scrubbed the countertop or mopped the floor? You managed to be conscious enough to complete complex tasks, but not conscious enough to truly realize that you were doing so.

Although unconscious processes guide a great number of our behaviors, we are also able to focus our attention, making conscious decisions about what to attend to. When driving, you might focus intently on a conversation you just had with your friend or an exam you will take in an hour. With this type of conscious activity we deliberately channel or direct our attention.

Selective Attention

LO 3 Describe how we narrow our focus on specific stimuli to attend to them.

This brings us to an important concept in understanding consciousness; although we have access to a great deal of information in our internal and external environments, we can only focus our attention on a small portion of that information at one time. This narrow focus on specific stimuli is known as selective attention. Researchers have found selective attention can be influenced by emotions. Anger, for example, increases our ability to selectively attend to something or someone (Finucane, 2011). So too does repeated exposure to stimuli (Brascamp, Blake, & Kristjánsson, 2011). We also get better at ignoring distractions as we age (Couperus, 2011).

This doesn’t mean other information isn’t being processed. We generally adapt to continuous input, ignoring the millions of unimportant sensory stimuli constantly bombarding us. Yet, we are designed to pay attention to abrupt, unexpected changes in the environment, and to stimuli that are unfamiliar or especially strong (Bahrick & Newell, 2008; Daffner et al., 2007; Parmentier & Andrés, 2010). Think about how you approach reading this chapter, for example. Your sensory systems are hard at work, but your focus remains on your reading.

Imagine you are studying in a busy courtyard. You are aware the environment is bustling with activity, but you fail to pay attention to every person. If something changes, though, your attention might be directed to that novelty. The same thing occurs when you are in a crowded room talking to someone. You are able to pay attention to your conversation despite all the noise from the many other conversations. This is known as the cocktail-party effect; you can block out the chatter and noise of the party and get lost in a deep conversation, a very efficient use of selective attention (Koch, Lawo, Fels, & Vorländer, 2011).

Inattentional Blindness

Selective attention is great if you need to study for a psychology test while others are watching TV, but it can also be dangerous. Suppose a friend sends you a hilarious text message while you are walking into a busy intersection. Thinking about the text can momentarily steal your attention away from signs of danger, like a car turning right on red without stopping. While distracted by the text message, it is completely possible you step into the intersection—without seeing the car turning in your path. This “looking without seeing” is referred to as inattentional blindness, and it can have serious consequences (Mack, 2003).

Ulric Neisser was the first to illustrate just how blind we can be to objects directly in our line of vision. In one of his studies, participants were instructed to watch a video of men passing a basketball from one person to another (Neisser, 1979; Neisser & Becklen, 1975). As they diligently followed the basketball with their eyes, counting each pass, a partially transparent woman holding an umbrella was superimposed walking across the basketball court. Only 21% of the participants even noticed the woman (Most et al., 2001; Simons, 2010); the others had been too fixated on the basketball to see her (Mack, 2003).

Levels of Consciousness

People often equate consciousness with being awake and alert, and unconsciousness as being passed out or comatose. But the distinction is not so clear, because there are different levels of conscious awareness including wakefulness, sleepiness, drug induced states, dreaming, hypnotic states, and meditative states, to name but a few. One way to define these levels of consciousness is to determine how much control you have over your awareness at the time. A high level of awareness might occur when focusing a lot of attention on a task (using a sharp knife); a lower level might occur when daydreaming, although you are able to snap out of it as needed. Sometimes we can identify an agent that causes a change in the level or state of consciousness. Psychologists typically delineate between waking consciousness and altered states of consciousness that may result from drugs, alcohol, or hypnosis—all topics covered later in the chapter.

Consciousness is like a swirling plume of smoke, always changing, seemingly impossible to grasp. But wherever your attention is focused at this moment, that is your conscious experience. There are times when attention essentially shuts down, however. What’s going on when we lie in bed motionless, lost in a peaceful slumber? Sleep, fascinating sleep, is the subject of our next section. Welcome to the world of consciousness and its many shades of gray.

show what you know

Question 4.1

1. When researchers try to study participants’ conscious experiences, one barrier they face is that consciousness is __________, pertaining only to the individual who experiences it.

subjective

Question 4.2

2. While studying for an exam, your sensory systems absorb an inordinate amount of information from your surroundings, most of which you are not aware of. Because of __________, generally you do not get overwhelmed with incoming sensory data.

- consciousness

- automatic processing

- depressants

- encoding

b. automatic processing

Question 4.3

3. Inattentional blindness is the tendency to “look without seeing.” Researchers have determined that most people do not notice a variety of events. Given what you know about selective attention, what advice would you give someone about defending against “looking without seeing”?

Answers will vary. The ability to focus awareness on a small segment of information that is available through our sensory systems is called selective attention. Although we are exposed to many different stimuli at once, we tend to pay particular attention to abrupt or unexpected changes in the environment. Such events may pose a danger and we need to be aware of them. However, selective attention can cause us to be blind to objects directly in our line of vision. This “looking without seeing” can have serious consequences, as we fail to see important occurrences in our surroundings. Our advice would be to try to remain aware of the possibility of inattentional blindness, in particular when you are in situations that could involve serious injury.