Dreams

Matt: What sorts of medications help to control narcolepsy?

Sleep is an exciting time for the brain. As we lie in the darkness, eyes closed and bodies limp, our neurons keep firing. REM is a particularly active sleep stage, when the brain waves are fast and irregular. During REM, anything is possible. We can soar through the clouds, kiss superheroes, and ride roller coasters with frogs. Time to explore the weird world of dreaming.

SLEEP, SLEEP, GO AWAY

Just 2 months before graduating from high school, Matt began taking a new medication that vastly improved the quality of his nighttime sleep. Taking this drug at set intervals was a key element in the dramatic improvement he experienced over the next few years. He also began strategic power napping, setting aside time in his schedule to go somewhere peaceful and fall asleep for 15 to 30 minutes. “Power naps are probably the greatest thing a person with narcolepsy can do,” Matt insists. The naps helped eliminate the daytime sleepiness, effectively preempting all those unplanned naps that had fragmented his days. Matt also worked diligently to create structure in his life, setting a predictable rhythm of going to bed, taking medication, going to bed again, waking up in the morning, attending class, taking a nap, and so on.

Just 2 months before graduating from high school, Matt began taking a new medication that vastly improved the quality of his nighttime sleep. Taking this drug at set intervals was a key element in the dramatic improvement he experienced over the next few years. He also began strategic power napping, setting aside time in his schedule to go somewhere peaceful and fall asleep for 15 to 30 minutes. “Power naps are probably the greatest thing a person with narcolepsy can do,” Matt insists. The naps helped eliminate the daytime sleepiness, effectively preempting all those unplanned naps that had fragmented his days. Matt also worked diligently to create structure in his life, setting a predictable rhythm of going to bed, taking medication, going to bed again, waking up in the morning, attending class, taking a nap, and so on.

Now a college graduate and working professional, Matt manages his narcolepsy quite successfully. All of his major symptoms—the spontaneous naps, cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations—have faded. “Now if I fall asleep, it’s because I choose to,” Matt says. “Most people don’t even know I have narcolepsy.”

Not everyone with narcolepsy is so fortunate. The disorder is often mistaken for another ailment, such as depression or insomnia. Most people with narcolepsy don’t even know they have it, and by the time an expert offers them a diagnosis (sometimes years after the symptoms began), they have already suffered major social and professional consequences (Stanford Center for Narcolepsy, 2012). While several medications are available to help control symptoms, there is no known cure for narcolepsy. Scheduling “therapeutic naps,” avoiding monotonous activities, and controlling emotional highs are all behavioral treatments for narcolepsy.

Now when Matt goes to sleep at night, he no longer imagines people coming to murder him. And instead of having nightmares, he dreams about soaring through the skies like Superman. Sometimes he cruises at the altitude of an airplane; other times he penetrates the earth’s outer atmosphere and barrels into outer space to visit the planets. “All my dreams are now pleasant,” says Matt, “[and] it’s a lot nicer being able to fly than being stabbed by a butcher knife.” And if you wonder what Matt is doing these days, he works at a credit union (he was just promoted) and is very busy remodeling his new home. Onward and upward, like Superman.

In Your Dreams

LO 7 Summarize the theories of why we dream.

What are dreams, and why do we have them? Dreams have been interpreted as messages from God, revelations of the future, and communication from spirits. People have contemplated the significance of dreams for millennia, resulting in many theories to explain why we dream.

Psychoanalysis and Dreams

The first comprehensive theory of dreaming was developed by the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (Chapter 11 and Chapter 14). In 1900 Freud laid out his theory in the now-classic The Interpretation of Dreams, proposing that dreams were a form of “wish fulfillment,” or a playing out of unconscious desires. As Freud saw it, many of the desires expressed in dreams are forbidden ones that would produce great anxiety in a dreamer if she were aware of them. In dreams, these desires are disguised so they can be experienced without danger of discovery. Freud believed dreams have two levels of content: manifest and latent. Manifest content, the apparent meaning of the dream, is the actual story line of the dream itself—what you remember when you wake up. Latent content contains the hidden meaning of the dream, which represents unconscious conflicts and desires. During therapy sessions, psychoanalysts use the latent content of dreams to uncover the unconscious, by looking deeper than the actual story line of the dream. Freud would ask patients to recount the manifest content and then look for symbols and other clues that might expose what is otherwise hidden because of its threatening nature; that is, the latent content.

Here’s an example: A painter arrives at Freud’s office and recounts a dream in which his wife destroys the canvas he has been working on for weeks. Freud might suggest the brush used by the painter’s wife is a symbol of the painter’s fear of his mother controlling his sexual activity. But critics of Freud’s approach to dream analysis would note there are an infinite number of ways to interpret any dream (all impossible to prove wrong). For example, maybe the underlying conflict in the painter is the lack of control he feels about his own work. Either interpretation could be correct, or perhaps his disturbing dream was simply the result of indigestion.

Activation-Synthesis Model

In contrast to Freud’s theory, the activation-synthesis model suggests that dreams have no meaning whatsoever (Hobson & McCarley, 1977). During REM sleep, the motor areas of the brain are inhibited (remember, the body is paralyzed), but sensory areas of the brain hum with the excitement of a great deal of neural activity. According to the activation–synthesis model, we respond to the random neural activity as if it has meaning. The brain tries to interpret this sensory excitement, which really is nothing more than neural chatter. This model suggests that our creative minds make up stories to match the neural activity. The brain is also trying to make sense of activity in the vestibular system, which is active during REM sleep. If the vestibular system is active while we are lying still, then the brain can interpret this as floating or flying—both common experiences reported by dreamers.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we noted that the vestibular system is responsible for our balance. Accordingly, if its associated area in the nervous system is active while we are asleep, the sensations normally associated with this system when we are awake will be interpreted in a congruent manner.

Neurocognitive Theory of Dreams

The neurocognitive theory of dreams proposes that a network of neurons exists in the brain, including some areas in the limbic system and the forebrain, that is necessary for dreaming to occur (Domhoff, 2001). People with damage to these areas of the brain either do not have dreams, or their dreams are not normal in some way. Another indication of the underlying neurocognitive nature of dreams is that children seem to develop the ability to dream, as their dreams are not like those of adults. For example, until children are around 13 to 15 years old, their reported dreams are less vivid and seem to have less of a story line. The underlying neural network must develop or mature before a child can dream like an adult. And as noted earlier, memory consolidation seems to be facilitated by sleep, with some theorists emphasizing the important role REM sleep plays in this process. The neurocognitive theory of dreams does not suggest, however, that dreams serve a purpose. Instead, they seem to be the result of how sleep and consciousness have evolved in humans (Domhoff, 2001).

Dream a Little Dream

Most dreams feature ordinary, everyday scenarios like driving or sitting in class. The content of dreams is repetitive and in line with what we think about when we are awake, and includes similar ideas about relationships, bad luck, people, and negative feelings. In fact, even over long periods of time and across cultures, the content of dreams is relatively consistent. Unfortunately, dreams are more likely to include sad events than happy ones. Despite popular assumptions, less than 12% of dream time is devoted to sexual activity (Yu & Fu, 2011). If you’re one of those people who believe they don’t dream, you are probably wrong. Most individuals who insist they don’t dream simply fail to remember their dreams. If you’re still skeptical, ask a bedmate to wake you next time it looks like you are in REM sleep (typical signs include eyes flitting side to side beneath the eyelids, and fingers and toes twitching). If awakened during a dream, you are more likely to be able to recall it at that moment than if asked to remember it at lunchtime. The ability to remember dreams is dependent on the length of time since the dream.

Most dreaming takes place during REM sleep and is jam-packed with rich sensory details and narrative. Dreams also occur during non-REM sleep, but they lack the vivid imagery and storylike quality of REM dreams. The average person starts dreaming about 90 minutes into sleep, then goes on to have about four to six dreams during the night. Add up the time and you get a total of about 1 to 2 hours of dreaming per night. Dreams happen in real time. In one early study investigating this phenomenon, researchers roused sleepers after they had been in a 5-minute REM cycle and again after a 15-minute REM cycle, asking them how long they had been dreaming (5 or 15 minutes). The majority of the participants—four out of five—gave the right answer (Dement & Kleitman, 1957).

Have you ever experienced the realization that you are in the middle of a dream? A lucid dream is a dream in which you are aware you are dreaming, and research suggests that about half of us have had one (Gackenbach & LaBerge, 1988). There are two parts to a lucid dream: the dream itself and the awareness that you are dreaming. Some suggest lucid dreaming is actually a way to direct the content of dreams (Gavie & Revonsuo, 2010), but this is a controversial claim because there is no way to confirm people’s subjective reports; dreams cannot be experienced by an outsider.

Fantastical, funny, frightening dreams can take many forms. Freud suggested that dreams unlock the mysteries of the unconscious mind. Contemporary scholars suspect that dreams are the result of neurocognitive activity. Others posit that dreams mean nothing and are merely the product of the brain’s efforts to make sense of the electrical traffic from sensory networks. What do dreams mean, and why do they happen? These are two of the great puzzles facing today’s psychologists. We know dreams represent a distinct state of consciousness, and consciousness is a fluid, ever-changing entity. But now it’s time to explore how consciousness transforms when chemicals are introduced into our bodies.

show what you know

Question 4.1

1. Freud believed dreams have two levels. The ________ refers to the apparent meaning of the dream, whereas the ________ refers to its hidden meaning.

manifest content; latent content

Question 4.2

2. According to the ________, dreams have no meaning whatsoever. Instead, the brain is responding to random neural activity as if it has meaning.

- psychoanalytic perspective

- neurocognitive theory

- activation-synthesis model

- evolutionary perspective

c. activation–synthesis model

Question 4.3

3. What occurs in the brain when you dream?

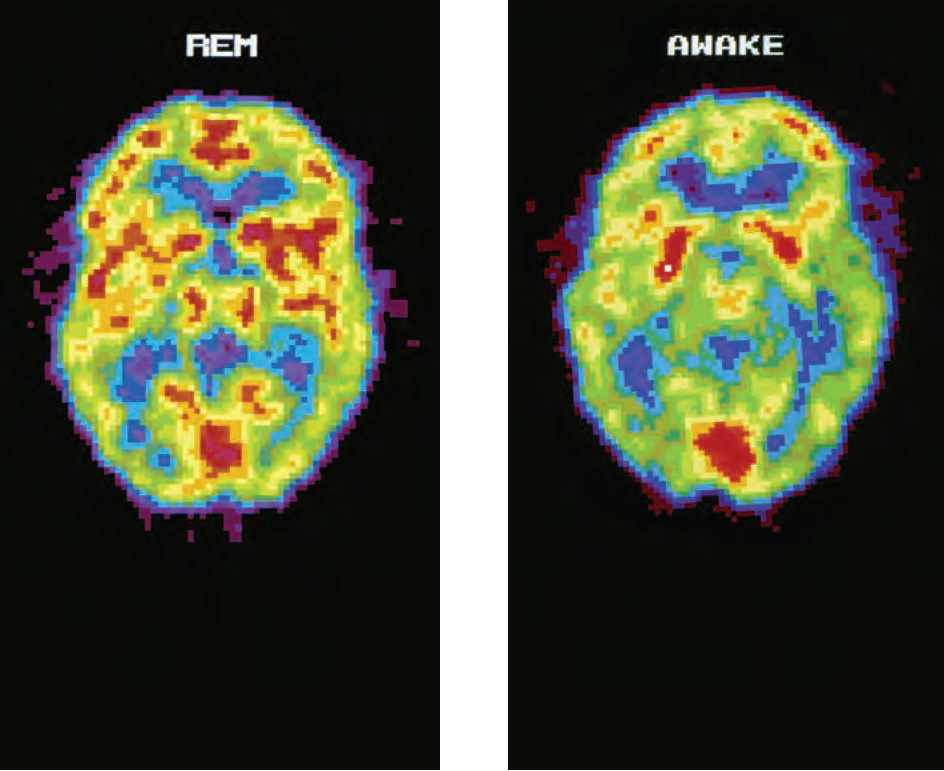

Electroencephalogram (EEG) and PET scan technologies can demonstrate neural activity of the sleeping brain. During REM sleep, the motor areas of the brain are inhibited, but a great deal of neural activity is occurring in the sensory areas of the brain. The activation–synthesis model suggests dreams result when the brain responds to this random neural activity as if it has meaning. The creative human mind makes up stories to match the neural activity. The vestibular system is also active during REM sleep, resulting in sensations of floating or flying. The neurocognitive theory of dreams proposes that a network of neurons in the brain (including some areas in the limbic system and forebrain) are necessary for dreaming to occur.

Question 4.4

4. Your 6-year-old cousin does not have dreams with a true story line; her dreams seem to be fleeting images. This supports the neurocognitive theory of dreams, as does the fact that:

- until children are around 13 to 15 years old, their reported dreams are less vivid.

- dream content is not the same across cultures.

- children younger than 13 can report very complicated story lines from their dreams.

- dream content is the same for people, regardless of age.

a. until children are around 13 to 15 years old, their reported dreams are less vivid.