6.4 The Reliability of Memory

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced the concepts of expectations and bias, noting that these can produce inaccuracies in thinking and research. Here, we will describe the ways in which our memories can fail. As accurate as our thoughts and memories may seem, we must be aware that they are vulnerable to error.

Why do we need computers to help us keep track of the loads of information flooding our brains throughout the day? The answer is simple. We can’t remember everything. We forget, and we forget often. Sometimes it’s obvious an error has occurred (I can’t remember where I left my cell phone), but other times it’s less apparent. Have you noticed that when you recall a shared event, your version is not always consistent with those of other people? As you will soon discover, memories are not reliable records of reality. They are malleable (that is, capable of being changed or reshaped by various influences) and constantly updated and revised, like a wiki. Let’s see how this occurs.

Misinformation

LO 11 Explain how the malleability of memory influences the recall of events.

Elizabeth Loftus, a renowned psychologist and law professor, has been studying memory and its reliability for the last 40 or more years. During the course of her career, she has been an expert witness in over 200 trials. The main focus of her work is the very problem we just touched upon: If two people have different memories of an event, whom do we believe? Loftus suggests that we should not expect our accounts of the past to be identical to those of other people or even of our own previous renditions of events. According to Loftus, episodic memories are not exact duplicates of past events (recent or distant). Instead, she and others propose a reconstructionist model of memory “in which memories are understood as creative blendings of fact and fiction” (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994, p. 5). Over the course of time, memories can fade, and because they are permeable, they become more vulnerable to the invasion of new information. In other words, your memory of some event might include revisions to what really happened, based on knowledge, opinions, and information you have acquired since the event occurred.

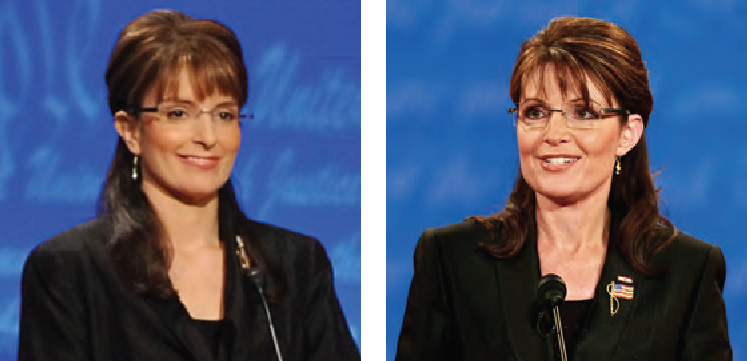

Suppose you watch a debate between two presidential candidates on live television. A few days later, you see that same debate parodied on Saturday Night Live. Then a few weeks later, you try to remember the details of the actual debate—the topics discussed, the phrases used by the candidates, the clothes they wore. In your effort to recall the real event, you may very well incorporate some elements of the Saturday Night Live skit (for example, words or expressions used by the candidates). Pulling information out of storage is not like pressing “play” on a digital recorder. The memories we make are not precise depictions of reality, but representations of the world as we perceive it. With the passage of time, we lose bits and pieces of a memory, and unknowingly we replace them with new information.

The Misinformation Effect

If you witnessed a car accident, how good do you think your memory of it would be? Elizabeth Loftus and John Palmer (1974) tested the reliability of people’s memories for such an event in a classic experiment. After showing participants a short film clip of a multiple-car accident, Loftus and Palmer quizzed them about what they had seen. They asked some participants, “About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” Replacing the word “smashed” with “hit,” they asked others, “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” Can you guess which version resulted in the highest estimates of speed? If you guessed “smashed,” you are correct.

One week later, the researchers asked the participants to recall the details of the accident, including whether they had seen any broken glass in the film. Although no broken glass appears in the film, the researchers nevertheless predicted there would be some “yes” answers from participants who had initially been asked about the speed of the cars that “smashed” into each other, as opposed to those who had heard the cars “hit” each other. And their predictions were correct. Participants who had heard the word “smashed” apparently incorporated a faster speed in their memories, and were more likely to report having seen broken glass. Participants who had not heard the word “smashed” seemed to have a more accurate memory of the filmed car collision. The researchers concluded that memories can be changed in response to new information. In this case, the participants’ recollections of the car accident were altered by the wording of a questionnaire (Loftus & Palmer, 1974). This research suggests that eyewitness accounts of accidents, crimes, and other important events might be altered by a variety of factors that come into play after the event occurs. Since memories are malleable, one must be careful when questioning people about the past, whether it’s in a therapist’s office, a police station, or at home talking with friends. The wording of questions can change the way events are recalled.

Researchers were fascinated with the findings from this initial study involving the car accident and have since conducted numerous studies on the misinformation effect, or the tendency for new and misleading information to distort one’s memory of an incident. Studies with a variety of participants have resulted in their “remembering” a stop sign that was really a yield sign, a screwdriver that was really a hammer, and a barn that did not actually exist (Loftus, 2005).

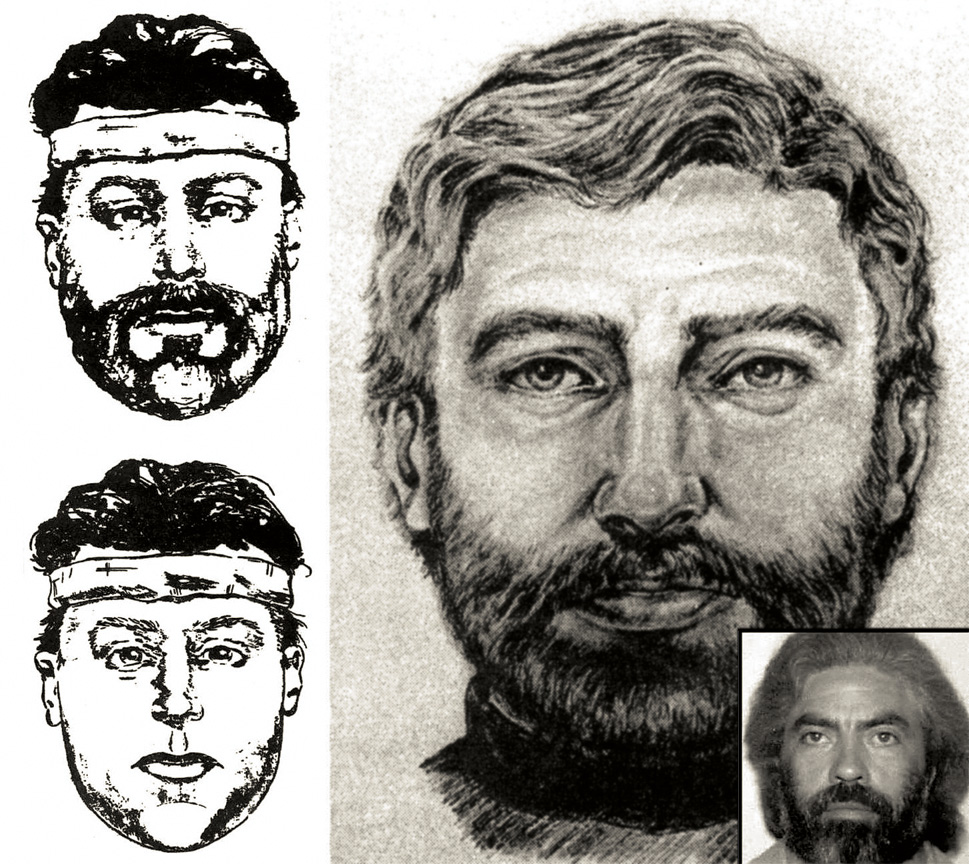

Prosecutors often tell people who have witnessed crimes not to speak to each other, and with good reason. Suppose two people witnessed an elderly woman being robbed. One eyewitness remembers seeing a bearded man wearing a blue hoodie swiping the woman’s purse. The other noticed the blue hoodie but not the beard. If, however, the two eyewitnesses exchange stories of what they saw, the second eyewitness may unknowingly incorporate the beard into his “memory.” Information learned after the event (that is, the “fact” that the thief had a beard) can unknowingly get mixed in with memories of that event (Loftus, 2005; Loftus, Miller, & Burns, 1978). If we can instill this type of “false” information into a “true” memory, do you suppose it is possible to give people memories for events that never happened? Indeed, it is.

False Memories

LO 12 Define rich false memory.

Elizabeth Loftus knows firsthand what it is like to have a memory implanted. Tragically, her mother drowned when she was 14 years old. For 30 years, she believed that someone else had found her mother’s body in a swimming pool. But then her uncle, in the middle of his 90th birthday party, told her that she, Elizabeth, had found her mother’s body. Loftus initially denied any memory of this horrifying experience, but as the days passed, she began to “recall” the event, including images of the pool, her mother’s body, and numerous police cars arriving at the scene. These images continued to build for several days, until she received a phone call from her brother informing her that her uncle had been wrong, and that all her other relatives agreed Elizabeth was not the one who found her mother. According to Loftus, “All it took was a suggestion, casually planted” (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994, p. 40), and she was able to create a memory of an event she never witnessed. Following this experience, Loftus began to study rich false memories, that is, “wholly false memories” characterized by “the subjective feeling that one is experiencing a genuine recollection, replete with sensory details, and even expressed with confidence and emotion, even though the event never happened” (Loftus & Bernstein, 2005, p. 101).

Would you believe that about 25% of participants in rich false memory studies are able to “remember” an event that never happened? Using the “lost in the mall” technique, Loftus and Pickrell (1995) showed just how these imaginary memories take form. The researchers recruited a pair of family members (for example, parent–child or sibling–sibling) and then told them they would be participating in a study on memory. With the help of one of the members of the pair (the “relative”), the researchers recorded three true events from the pair’s shared past and created a plausible story of a trip to a shopping mall that never happened. Then they asked the true “participant” to recall as many details as possible about each of the four events (remember, only three of the events were real), which were presented in a book provided by the researchers. If the participant could not remember any details from an event, he was instructed to write, “I do not remember this.” In the “lost in the mall” story, the participant was told that he had been separated from the family in a shopping mall around the age of 5. According to the story, the participant began to cry, but was eventually helped by an elderly woman and was reunited with his family. Mind you, the “lost in the mall” episode was pure fiction, but it was made to seem real through the help of the participant’s relative (who was working with the researchers). Following a series of interviews, the researchers concluded that 29% of the participants were able to recall either part or all of the fabricated “lost in the mall” experience (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995). These findings may seem shocking (they certainly caused a great uproar in the field), but keep in mind that the great majority of the participants did not “remember” the fabricated event (Hyman, Husband, & Billings, 1995; Loftus & Pickrell, 1995).

CONTROVERSIES

The Debate over Repressed Childhood Memories

Given what you learned from the “lost in the mall” study, do you think it’s possible that false memories can be planted in psychotherapy? Imagine a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist who firmly believes that her client was sexually abused as a child. The client has no memory of abuse, but the therapist is convinced that the abuse occurred and that the traumatic memory for it has been repressed, or unconsciously pushed below the threshold of awareness. Using methods such as hypnosis and dream analysis, the therapist helps the client resurrect a “memory” of the abuse (that presumably never occurred). Angry and hurt, the client then confronts the “abuser,” who happens to be a close relative, and forever damages the relationship. Believe it or not, this scenario is very realistic. Consider these true stories picked from a long list:

Given what you learned from the “lost in the mall” study, do you think it’s possible that false memories can be planted in psychotherapy? Imagine a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist who firmly believes that her client was sexually abused as a child. The client has no memory of abuse, but the therapist is convinced that the abuse occurred and that the traumatic memory for it has been repressed, or unconsciously pushed below the threshold of awareness. Using methods such as hypnosis and dream analysis, the therapist helps the client resurrect a “memory” of the abuse (that presumably never occurred). Angry and hurt, the client then confronts the “abuser,” who happens to be a close relative, and forever damages the relationship. Believe it or not, this scenario is very realistic. Consider these true stories picked from a long list:

- With the help of a psychiatrist, Nadean Cool came to believe that she was a victim of sexual abuse, a former member of a satanic cult, and a baby killer. She later claimed these to be false memories brought about in therapy (Loftus, 1997).

- Under the influence of prescription drugs and persuasive therapists, Lynn Price Gondolf became convinced that her parents molested her during childhood. Three years after accusing her parents of such abuse, she concluded the accusation was a mistake (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994).

- Laura Pasley “walked into her Texas therapist’s office with one problem, bulimia, and walked out with another, incest” (Loftus, 1994, p. 44).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 4, we described hypnosis as an altered state of consciousness that allows for changes in perceptions and behavior that result from suggestions made by the hypnotist. Here, we discuss the use of hypnosis in a therapeutic setting, in which the hypnotist is a therapist trying to help a client “remember” an abuse that the therapist believes has been repressed.

In the history of psychology, few topics have stirred up as much controversy as repressed memories. Some psychologists believe that painful memories can indeed be repressed and recovered years or decades later (Knapp & VandeCreek, 2000). The majority, however, would agree that the studies supporting the existence of repressed memories have many shortcomings (Piper, Lillevik, & Kritzer, 2008). Although childhood sexual abuse is shockingly common, affecting some 30–40% of girls (about 1 in 3) and 13% of boys (about 1 in 8) in the United States (Bolen & Scannapieco, 1999), there is not good evidence that these traumas are repressed. Even if they were, retrieved memories of them would likely be inaccurate (Roediger & Bergman, 1998). Many trauma survivors face quite a different challenge—letting go of painful memories that continue to haunt them. (See the discussion of posttraumatic stress disorder in Chapter 12.)

REAL OR IMAGINED?

The American Psychological Association (APA) and other authoritative mental health organizations have investigated the repressed memory issue at length. In 1998 the APA issued a statement offering its main conclusions, summarized below:

- Sexual abuse of children is very common and often unrecognized, and the repressed memory debate should not detract attention from this important issue.

- Most victims of sexual abuse have at least some memory of the abuse.

- Memories of past abuses can be forgotten and remembered at a later time.

- People sometimes do create false memories of experiences they never had.

- We still do not completely understand how accurate and flawed memories of childhood abuse are formed (APA, 1998a).

The main message of this section is that memory is malleable, or changeable. What are the implications for eyewitness accounts, especially those provided by children? If we are aware of how questions are structured and understand rewards and punishments from the perspective of a child, then the interview will produce fewer inaccuracies (Sparling, Wilder, Kondash, Boyle, & Compton, 2011). Researchers have found that having children close their eyes increases the accuracy of the testimony (Vrede-veldt, Baddeley, & Hitch, 2013), but relying solely on their accounts has contributed to many cases of mistaken identity. In addition, the presence of someone in a uniform appears to put added pressure on child eyewitnesses, resulting in more guessing and inaccurate recall (Lowenstein, Blank, & Sauer, 2010).

Before you read on, take a minute and allow the words of Elizabeth Loftus to sink in: “Think of your mind as a bowl filled with clear water. Now imagine each memory as a teaspoon of milk stirred into the water. Every adult mind holds thousands of these murky memories…. Who among us would dare to disentangle the water from the milk?” (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994, p–4). What is the basis for all this murkiness? Time to explore the biological roots of memory.

show what you know

Question 6.15

1. The __________ refers to the tendency for new and misleading information to distort memories.

misinformation effect

Question 6.16

2. Your uncle claims he attended a school play in which you played the “Cowardly Lion.” He has described the costume you wore, the lines you mixed up, and even the flowers he gave you. At first you can’t remember the play, but eventually you seem to. Your mother insists you were never in that school play, and your uncle wasn’t in the country that year, so he couldn’t have attended the performance at all. Instead, you have experienced a:

- curve of forgetting.

- state-dependent memory.

- savings score.

- rich false memory.

d. rich false memory.

Question 6.17

3. Loftus and Palmer (1974) conducted an experiment in which the wording of a question (using “smash” versus “hit”) significantly influenced participants’ recall of the event. What does this suggest about the malleability, or changeability, of memory?

A reconstructionist model of memory suggests that memories are a combination of “fact and fiction.” Over time, memories can fade, and because they are permeable, they become more vulnerable to the invasion of new information. In other words, memory of an event might include revisions to what really happened, based on knowledge, opinions, and information you have gained since the event occurred. The Loftus and Palmer experiment indicates that the wording of questions can significantly influence recall, demonstrating that memories can change in response to new information (that is, they are malleable).