8.1 The Study of Human Development

human development

A DAY IN THE LIFE

The Study of Human Development

A DAY IN THE LIFE

Montgomery, Illinois: Mondays are especially hectic for working mom and college student Jasmine Mitchell. The 31-year-old starts the day at 5:00 a.m. with a morning workout of hip-swaying, shoulder-shimmying Zumba® dance. Then, in between catching her breath and folding laundry, she wakes up her 14-year-old daughter Jocelyn and her 5-year-old son Eddie. At 7:00 a.m., two more children appear at Jasmine’s doorstep, a 14-year-old nephew and a 9-year-old niece. Jasmine takes care of the kids in the morning to help out her mother, who is their legal guardian. It is now 7:15 a.m., and Jasmine is fixing eggs and sausage for a house full of children.

Meanwhile, in Austin, Texas, 22-year-old Chloe Ojeah is dropping an array of multicolored pills into her grandparents’ pill dividers. This painstaking task is something she needs to do carefully because it’s critical that both her grandmother and grandfather take the correct medication in the morning and again at night. Her 79-year-old grandmother is struggling with Alzheimer’s disease and her 85-year-old grandfather is recovering from a stroke. After skipping breakfast herself, Chloe heads out the door and drives to Austin Community College, where she is working toward a degree in communications and, down the road, a career in teaching.

Back in Illinois, the time is now 8:30 a.m., and Jasmine has already dropped off the four children in her early morning care at three different schools. She returns home, cleans up the mess from breakfast, showers, and then starts her homework. Jasmine is studying to become a social worker at Waubonsee Community College, where she also works 40 hours a week as a receptionist. Not much time remains for studying, because Jasmine needs to arrive at work by 11:00 a.m.

Right around the time Jasmine walks into the office, Chloe is returning home from her morning class. She checks in with her grandparents’ caregiver (How did the morning go? Do we need anything from the store?), chats with her grandfather, grabs lunch, and hits the books. Within a few hours, she is cooking dinner—enchiladas, a cheeseburger pie, or something else warm and comforting—and dispensing her grandparents’ evening pills. During supper, they discuss the news, the family business, or whatever happens to be on their minds. Sometimes in midconversation, Chloe’s grandmother stares blankly at the window, a sign that she has lost track of the conversation.

Back in Illinois, Jasmine is just about to leave work. Around 8:30 p.m., she arrives at the home of her mother, who has picked up the kids at the end of their school day and cooked dinner for them. Once home, Eddie heads straight to bed and Jocelyn stays up late, working on homework. After finishing her own homework and tying up some odds and ends around the house, Jasmine finally goes to bed at 11:00 p.m.

It’s nighttime in Texas, and Chloe is sitting footsteps away from her grandparents’ bedroom. They’ve long since retired. She likes to stay close by, though, until 11:00 p.m., just in case they need her for some reason. Finally, in the silence of the night, Chloe climbs the stairs and crawls into bed.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

after reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- LO 1 Define human development.

- LO 2 Describe three longstanding discussions in developmental psychology.

- LO 3 Identify the types of research psychologists use to study developmental processes.

- LO 4 Examine the role genes play in our development.

- LO 5 Discuss how genotype and phenotype relate to development.

- LO 6 Identify the progression of prenatal development.

- LO 7 Summarize some developmental changes that occur in infancy.

- LO 8 Describe the theories explaining language acquisition.

- LO 9 Examine the universal sequence of language development.

- LO 10 Summarize the constructs of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.

- LO 11 List the key elements of Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development.

- LO 12 Identify how Erikson’s theory explains psychosocial development through puberty.

- LO 13 Give examples of significant physical changes that occur during adolescence.

- LO 14 Explain how Piaget described cognitive changes that take place during adolescence.

- LO 15 Identify how Erikson explained changes in identity during adolescence.

- LO 16 Summarize Kohlberg’s levels of moral development.

- LO 17 Name some of the physical changes that occur across adulthood.

- LO 18 Identify some of the cognitive changes that occur across adulthood.

- LO 19 Explain some of the socioemotional changes that occur across adulthood.

- LO 20 Summarize the four types of parenting proposed by Baumrind.

- LO 21 Describe how Kübler-Ross explained the stages of death.

Other Voices: Allie Fuentes

Jasmine Mitchell and Chloe Ojeah are actual college students with real-world responsibilities. They are pursuing challenging degree programs, launching careers, and finding their place in the world. Both women are making their way through a busy, often tumultuous, period of life called young adulthood. At the same time, they are up to their necks in issues pertinent to other stages of life: childhood and adolescence for Jasmine, the young mother, and late adulthood for Chloe, the caretaker of two elderly family members.

Here, we feature the stories of these young women because they are people whose lives, in many respects, may resemble your own. Psychologists often focus their research on “normal” or “average” individuals, as it helps them uncover universal or common themes and variations across the life span.

Allie Fuentes: How does being a parent affect your work and school?

LO 1 Define human development.

Developmental Psychology

What do psychologists mean when they say “development”? Obviously, humans do not stay the same from conception to death. Development refers to the changes in our bodies, minds, and social functioning. The goal of developmental psychology is to examine these changes. The study of development is, in many ways, an attempt to understand the struggles and triumphs of everyday people at different stages of their lives. Many of the topics presented in this chapter, such as personality, learning, and emotion, are covered elsewhere in this book. Here, we focus on how these change over the course of a lifetime, homing in on three major categories of developmental change: physical, cognitive, and socioemotional.

Physical Development

Physical development begins the moment a sperm unites with an egg, and it continues until we take our final breath. Human development is influenced by the genes we inherit from our biological parents, the hormones circulating in our bloodstream, and many other biological factors. The physical growth beginning with conception and ending when the body stops growing is referred to as maturation. For the most part, this maturation follows a progression that is universal in nature and biologically driven, as these changes are common across all cultures and ethnicities, and generally follow a predictable pattern. Most babies, for example, become physically capable of sitting up alone at approximately 5½ months (ranging from 4 to 9 months; WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, 2006). After maturation, physical changes continue, but not necessarily in a positive or growth direction; for example, many older adults begin to have trouble seeing at night (Stuen & Faye, 2003).

Cognitive Development

Changes in memory, problem-solving abilities, decision making, language, and intelligence all fall under the umbrella of cognitive development. Like physical development, cognitive development tends to follow a universal course early in life. Infants, for example, begin to babble around the age of 7 months and say their first words around 12 months. But there is enormous variation in the way cognitive abilities change, particularly as people get older (Skirbekk, Loichinger, & Weber, 2012; Small, Dixon, & McArdle, 2012; von Stumm & Deary, 2012). Chloe’s 85-year-old grandfather won’t necessarily have the same cognitive abilities as his 85-year-old neighbor, whose memory and wit may not be as sharp.

Socioemotional Development

Socioemotional development refers to social behaviors, emotions, and the changes people experience with respect to their relationships, feelings, and overall disposition. A developmental psychologist studying Jasmine and her family might look at how Jasmine’s relationship with her mother has changed over time, or how her children have developed close bonds with their cousins. They might be interested in learning how Jasmine’s approach to motherhood changed in the decade between Jocelyn and Eddies’ births.

Biopsychosocial Perspective

In this chapter, we draw on the biopsychosocial perspective, which recognizes the contributions of biological, psychological, and social forces shaping human development. We consider the intricate interplay of heredity, chemical activity, and hormones (biological factors); learning and personality traits (psychological factors); and family, culture, and media (social factors). When examining and explaining complex psychological phenomena, it is important to incorporate a variety of approaches.

Three Debates

LO 2 Describe three longstanding discussions in developmental psychology.

Science is, at its core, a work in progress, full of unresolved questions and areas of disagreement. In developmental psychology, longstanding debates and discussions tend to cluster around three major themes: stages and continuity, nature and nurture, and stability and change. Each of these themes relates to a basic question: (1) Does development occur in separate or discrete stages, or is it a steady, continuous process? (2) What are the relative roles of heredity and environment in development? (3) How stable is one’s personality over a lifetime and across situations?

Stages or Continuity

Some aspects of development occur in discrete stages; others in a steady, continuous process. Abrupt changes are often related to environmental circumstances. High school graduation, for example, marks the time when many young people feel free to move out of the family home. This response is not universal, however. Chloe graduated from high school years ago, but she is living with her grandparents so she can care for them. Physical changes may also occur in stages, such as learning to walk and talk, or developing the physical characteristics of a sexually mature adult.

One line of evidence supporting developmental stages with definitive beginnings and endings comes to us indirectly through the animal kingdom. Konrad Lorenz (1937) was one of the first researchers to document the imprinting phenomenon, showing, for example, that when baby geese hatch, they become attached to the first “moving and sound-emitting object” they see, whether it’s their mother or a nearby human. Lorenz made sure he was the first moving creature several goslings saw, and he found that they followed him as soon as they could stand up and walk, becoming permanently attached to him because he was that first “object.” But there appeared to be a limited time frame within which this imprinting occurred. Experiences during a critical period for this type of automatic response result in permanent and “irreversible changes” in brain function (Knudsen, 2004). Critical periods are a type of sensitive period of development, during which “certain capacities are readily shaped or altered by experience”. Young barn owls, for example, learn how to navigate their environment during a sensitive period in which auditory information is used to create a type of mental map, but this period is not considered critical because it is not characterized by irreversible brain changes (Knudsen, 2004).

How does all this talk of geese and owls relate to people? Some psychologists suggest there is a critical period for language acquisition. Until a certain age, children are highly receptive to learning language, but after that critical period ends, it is difficult for them to acquire a first language that is age-appropriate and “normal” (Kuhl, Conboy, Padden, Nelson, & Pruitt, 2005). Others suggest that language acquisition is not subject to a critical period, but rather to sensitive periods that all children experience (Knudsen, 2004). (For more on this topic, read about Genie the “feral child” later in this chapter.)

Although some aspects of development occur in stages, others occur gradually, without a clear distinction between them (McAdams & Olson, 2010). Observing a toddler making her transition into early childhood, you probably won’t be able to pinpoint her shift from the “terrible twos” to the more emotionally self-controlled young child.

Hereditary and Environmental Influences

Psychologists also debate the degree to which heredity (nature) and environment (nurture) influence behavior and development, but few would dispute the important contributions of both (Mysterud, 2003). Researchers can study a trait like impulsivity, which is the tendency to act before thinking, to determine the extent to which it results from hereditary factors and environment. In this particular case, nature and nurture appear to have equal weight (Bezdjian, Baker, & Tuvblad, 2011). Later in this chapter, we will examine the balance of nature and nurture in relation to brain and intellectual development, a longstanding, sometimes controversial debate in psychology and beyond.

Stability and Change

How much does a person change from childhood to old age? Some researchers suggest that personality traits identified early in life can be used to predict behaviors across the life span (McAdams & Olson, 2010). Others report that personality characteristics change as a result of the relationships and experiences we have throughout life (Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2011). Psychologists often discuss how experiences in infancy can set the stage for stable cognitive characteristics, particularly when it comes to early enrichment and its long-term impact on intellectual abilities (more on this topic later).

Three Methods

LO 3 Identify the types of research psychologists use to study developmental processes.

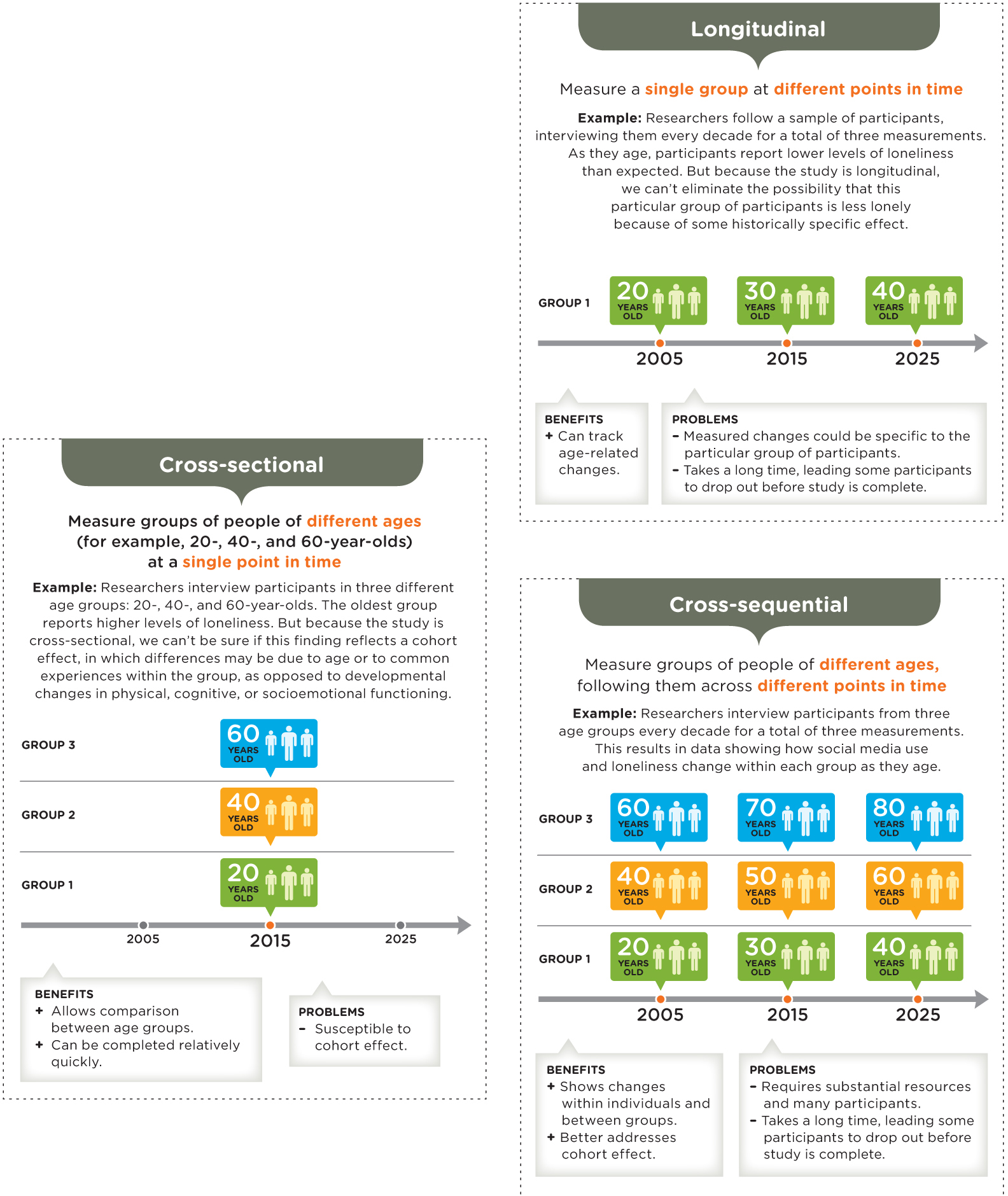

Developmental psychologists use a variety of methods to study differences across ages and time (Infographic 8.1).

The Cross-Sectional Method

The cross-sectional method enables researchers to examine people of different ages at one point in time. For example, Castel and his colleagues (2011) used the cross-sectional method to investigate developmental changes in the efficiency of memory recall. They divided their 320 participants into groups according to age (children, adolescents, younger adults, middle-aged adults, young-old adults, and old-old adults) and compared the scores of the different groups to see if changes occur across the life span. One advantage of the cross-sectional method is that it can provide a great deal of information quickly; by studying differences across age groups, we don’t have to wait for people to get older.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 6, we described recall as the process of retrieving information held in long-term memory without the help of explicit retrieval cues. Here, we will see how these memory processes change as a function of development.

But a major problem with the cross-sectional method is that it doesn’t tell us whether differences across age groups result from actual developmental changes or common experiences within groups, a phenomenon known as the cohort effect. Members of each age group have lived through similar historical and cultural eras, and these common experiences may be responsible for some differences across groups. For example, the “old-old adults” in the memory recall study described above probably have different perspectives than those in the younger adult group. They were not raised on cell phones, iPads, computers, Google, or Facebook. The authors of the study were quick to point out this pitfall: “The present design was cross-sectional, whereas (in some ways) a longitudinal design would allow for stronger conclusions regarding…changes with age” (Castel et al., 2011, p. 1562).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described confounding variables as unaccounted factors that change in sync with the independent variable, making it very hard to discern which one is causing changes in the dependent variable. Here, we consider how a cohort can act as a confounding variable.

The Longitudinal Method

Researchers can avoid the cohort effect by using the longitudinal method, which follows one group of individuals over a period of time. Curious to find out what “lifestyle activities” are associated with age-related cognitive decline, one team of researchers studied 952 individuals over a 12-year period (Small, Dixon, McArdle, & Grimm, 2011). Every 3 to 4 years, they administered tests to all participants, assessing, for example, cognitive abilities and health status. The more engaged and socially active the participants were, the better their long-term cognitive performance. Using the longitudinal method, we can compare the same individuals over time, identifying similarities and differences in the way they age. But these studies are difficult to conduct because they require a great deal of money, time, and participant investment. Common challenges include attrition (people dropping out of the study) and practice effects (people performing better on measures as they get more “practice”). The advantage, though, is that changes are tracked within the same people, to avoid the cohort effect of an era or generation.

The Cross-Sequential Method

The cross-sequential method, also used by developmental psychologists, is a mixture of the longitudinal and cross-sectional methods. You might call it the best of both worlds. Participants are divided into age groups as well as followed over time, so researchers can examine developmental changes within individuals and across different age groups. One team of researchers used this approach to identify the age at which cognitive decline becomes evident (Singh-Manoux et al., 2012). They recruited 10,308 participants, assigning each to a 5-year age group (45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, and 65–70), and then followed them for 10 years. Using this approach, they could observe changes in individuals as they aged and identify differences across the five age groups.

INFOGRAPHIC 8.1: Research Methods in Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychologists use several research methods to study changes that occur with age. Imagine you want to know whether using social media helps protect against feelings of loneliness over time. How would you design a study to measure that? Let’s compare methods.

Human development is very complex. Some processes are universal; others are specific to an individual, and it is this combination that makes the field so fascinating. As you learn about the development of Chloe, Jasmine, and their families, you may be struck by the degree of similarity (or differences) in your own family.

show what you know

Question 8.1

1. A 3-year-old decides he doesn’t need diapers, and much to his parents’ surprise, he starts using the toilet. This physiological change likely results from his maturation, which follows a progression that is universal and biologically driven. This is an example of human ________, which includes changes in physical, cognitive, and socioemotional characteristics.

development

Question 8.2

2. Explain the three longstanding discussions of developmental psychology.

Developmental psychologists’ longstanding discussions have centered on three major themes: stages and continuity; nature and nurture; and stability and change. Each of these themes relates to a basic question: (1) Does development occur in separate or discrete stages, or is it a steady, continuous process? (2) What are the relative roles of heredity and environment in human development? (3) How stable is one’s personality over a lifetime and across situations?

Question 8.3

3. A researcher is interested in studying developmental changes in memory recall. She asks 300 participants to take a memory test and then compares the results across five different age groups. This researcher is using which of the following methods?

- cross-sequential

- longitudinal

- cross-sectional

- biopsychosocial

c. cross-sectional