8.4 Adolescence

THE WALKING, TALKING HORMONE

Jocelyn is no longer a cute little bundle of girlhood; nowadays, she is a “walking, talking hormone,” says Jasmine. “Boys, make-up, and friends are the center of her world now.” At age 14, Jocelyn can also be mouthy; she cares a lot about what other people think of her; and she is mortified by her 31-year-old mother whom she thinks of as “so old.” There are times when Jocelyn blatantly disregards her mother’s instructions. She might, for example, go to a friend’s house even after Jasmine has explicitly denied her permission to do so.

Jocelyn is no longer a cute little bundle of girlhood; nowadays, she is a “walking, talking hormone,” says Jasmine. “Boys, make-up, and friends are the center of her world now.” At age 14, Jocelyn can also be mouthy; she cares a lot about what other people think of her; and she is mortified by her 31-year-old mother whom she thinks of as “so old.” There are times when Jocelyn blatantly disregards her mother’s instructions. She might, for example, go to a friend’s house even after Jasmine has explicitly denied her permission to do so.

Jocelyn’s behaviors are stereotypical of teenagers, or adolescents. Adolescence refers to the transition period between late childhood and early adulthood, and it can be challenging for both parents and kids. As you may recall from earlier in the chapter, Jasmine proved to be quite a challenge for her own mom when she was a teen, skipping school and carousing until late at night with friends. “At 14, I had already started the crazy life,” says Jasmine, who considers herself blessed to have a daughter like Jocelyn, who gets As and Bs in school, doesn’t use drugs or alcohol, and participates in her school’s volleyball, basketball, and dance teams.

Allie Fuentes: How has your relationship with your son changed as he's entered adolescence?

In the United States, adult responsibilities often are distant concepts for adolescents. But, this is not universal. For example, in underdeveloped countries, children take on adult responsibilities as soon as they are able. In some parts of the world, girls younger than 18 are already married and dealing with adult responsibilities. In Bolivia, girls can legally marry at 14 years old (Nour, 2009). However, adolescence generally allows for a much slower transition to adult duties in America. Although adolescents might develop adult bodies, including the ability to become parents, here their schooling and training generally do not occur at the same adult level, in part because of longer periods of required education and dependence on parents and caregivers.

Physical and Cognitive Development in Adolescence

Physical Development

LO 13 Give examples of significant physical changes that occur during adolescence.

Adolescence is a time of dramatic physical growth, comparable to that which occurs during fetal development. The “growth spurt” includes rapid changes in height, weight, and bone growth, and usually begins between ages 9 and 10 years for girls and ages 12 and 16 years for boys. Sex hormones, which influence this growth and development, are at high levels.

Puberty is the period during which the body changes and becomes sexually mature and able to reproduce. During puberty, the primary sex characteristics or reproductive organs (ovaries, uterus, vagina, penis, scrotum, and testes) mature. In addition, the secondary sex characteristics, which are not associated with reproduction, become more distinct and include the development of pubic, underarm, and body hair. Breast changes also occur in boys and girls (with the areola increasing in size), and fat increases in girls’ breasts. Adolescents experience changes to their skin and overall body hair. Girls’ pelvises begin to broaden, while boys experience a deepening of their voices and broadening of their shoulders.

It is during this time that girls will experience menarche (ˈme-ˌnär-kē), the point at which menstruation begins. Menarche can occur as early as age 9 or after age 14; but typical onset is around 12 or 13. Boys experience spermarche (ˈspər-ˌmär-kē), their first ejaculation, during this time period as well. But, when it occurs is more difficult to specify, as boys may be reluctant to talk about the event (Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, & Graber, 2010).

Not everyone matures at the same time, however. Some evidence suggests that early maturing adolescents face a greater risk of engaging in unsafe behaviors, such as drug and alcohol use (Shelton & van den Bree, 2010). Compared to their peers, girls who mature early seem to experience more negative outcomes than those who mature later, such as increased social anxiety; they also appear to face a higher risk of emotional problems and delinquent behaviors (Blumenthal et al., 2011; Harden & Mendle, 2012). Early maturing girls are more likely to smoke, drink alcohol, have lower self-confidence, and later take on jobs that are “less prestigious.” There are certain factors that can reduce such risks, though, including parents who show warmth and support (Shelton & van den Bree, 2010).

Boys who mature early generally have a more positive experience and do not show evidence of increased anxiety (Blumenthal et al., 2011). But, when researchers examine the “tempo,” or speed, with which boys reach full sexual maturity, they find that rapid development can be associated with a range of problems, including aggressive behavior, cheating, and temper tantrums (Marceau, Ram, Houts, Grimm, & Susman, 2011).

Adolescence is a time when sexual interest peaks, yet teenagers don’t always make the best choices when it comes to sexual activity. A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2008a) found that over 25% of girls (approximately 1 of every 4) between ages 14 and 19 are infected with “at least one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases”. Over half of new sexually transmitted infections affect young people ages 15–24; keep in mind that this group represents only 25% of the sexually active population (CDC, 2013). Sexually transmitted infections are especially risky for adolescents because they often go untreated and can lead to a host of problems, including long-term sterility.

Cognitive Development

LO 14 Explain how Piaget described cognitive changes that take place during adolescence.

Alongside the remarkable physical changes of adolescence are equally remarkable cognitive developments. As noted earlier, children in this age range are better able to distinguish between abstract and hypothetical situations. This ability is an indication the teenager has entered Piaget’s formal operational stage, which begins in adolescence and continues into adulthood. During this period, the adolescent begins to use deductive reasoning to draw conclusions and critical thinking to approach arguments. She can reason abstractly, classify ideas, and use symbols. The adolescent can think beyond what is going on in the moment, pondering the future and considering many possibilities or hypothetical situations. She may also begin to contemplate what will happen beyond high school, including career choices and education.

A specific type of egocentrism emerges in adolescence. Before this age, children can only imagine the world from their own perspective, but during adolescence they begin to become aware of others’ perspectives. Egocentrism is still apparent, however, as they believe others share their preoccupations. For example, a teenager who focuses on his appearance will think that others are focusing on his appearance as well (Elkind, 1967). Adolescents also tend to believe that everyone thinks the same way they do.

Adolescent egocentrism also helps explain the sense of uniqueness many teenagers feel. This intense focus on the self may lead to a feeling of immortality, which can result in risk-taking behaviors (Elkind, 1967). Because they have not had many life experiences, adolescents may fail to consider the long-term consequences of their behaviors. Nor is the logic used by adolescents the same as that used by adults. In particular, adolescents may not think about what might happen if they participate in risky behaviors (such as unprotected sex or drug use). Their focus on the present (for example, having fun in the moment) outweighs their ability to assess the potential harm in the future (pregnancy or addiction). So to help adolescents stop engaging in risky behaviors such as smoking, we might focus on short-term consequences, like bad breath when kissing a partner, rather than long-term dangers such as lung cancer (Robbins & Bryan, 2004).

The Adolescent Brain

Risk taking in adolescence is thought to result from characteristics of the adolescent brain. The limbic system, which is responsible for processing emotions and perceiving rewards and punishments, undergoes significant development during adolescence. Another important change is the increased myelination of axons in the prefrontal cortex, which improves the connections within the brain involved in planning, weighing consequences, and multitasking (Steinberg, 2012). But the relatively quicker development of the limbic system in comparison to the prefrontal cortex can lead to risk-taking behavior. Because the prefrontal cortex has not yet fully developed, the adolescent may not foresee the possible consequences of reward-seeking activities that are supported by the reward center of the limbic system. Changes to the structure of the brain continue through adolescence, resulting in a fully adult brain between the ages of 22 and 25, and a decline in risk-taking behaviors (Giedd et al., 2009; Steinberg, 2010, 2012).

Given this state of affairs, should adolescents be tried as adults in our legal system? In 2005 the U.S. Supreme Court ended the juvenile death penalty with its Roper v. Simmons decision (Borra, 2005). But the studies on brain structure provide results for groups, which may not apply to every individual. We cannot use such findings to draw definitive conclusions about individual teenagers (Bonnie & Scott, 2013).

Socioemotional Development in Adolescence

Adolescence is also a time of great socioemotional development. During this time, children become more independent from their parents. Conflicts may result as the adolescent searches for his identity, or sense of who he is based on his values, beliefs, and goals. Until this point in development, the child’s identity was based primarily on the parents’ or caregivers’ values and beliefs. Adolescents explore who they are by trying out different ideas in a variety of categories, including politics and religion. Once these areas have been explored, they begin to commit to a particular set of beliefs and attitudes, making decisions to engage in activities related to their evolving identity. One word of caution is in order: Their commitment may shift back and forth, sometimes on a day-to-day basis (Klimstra et al., 2010).

Erikson and Adolescence

LO 15 Identify how Erikson explained changes in identity during adolescence.

Erikson’s theory of development addresses this important issue of identity formation (Erikson & Erikson, 1997). The time from puberty to the twenties is the stage of ego identity versus role confusion, which is marked by the creation of an adult identity. The adolescent strives to define himself. If the tasks and crises of Erikson’s first four psychosocial stages have not been successfully resolved, the adolescent may enter this stage with distrust toward others, and feelings of shame, guilt, and inadequacy. In order to be accepted, he may try to be all things to all people.

It is during this period that one wrestles with some important life questions: What career do I want to pursue? What kind of relationship should I have with my parents? What religion (if any) is compatible with my views, beliefs, and goals? This stage often involves “trying out” different roles. A person who resolves this stage successfully emerges with a stronger sense of her values, beliefs, and goals. One who fails to resolve role confusion will not have a solid sense of identity and may experience withdrawal, isolation, or continued role confusion. However, just because we reach adulthood doesn’t mean our identity stops evolving. As we will soon see, there is still plenty of growth throughout life.

Parents and Adolescents

What role does a parent play during this difficult period? Generally speaking, parent–adolescent relationships are positive (Paikoff & Brooks-Gunn, 1991), but conflict does increase during early adolescence (Van Doorn, Branje, & Meeus, 2011), and it frequently relates to issues of control and parental authority. Often these parent–teen struggles revolve around everyday issues such as curfew, chores, schoolwork, and personal hygiene. Fortunately, conflict tends to decline as both parties become more comfortable with the adolescents’ growing sense of autonomy and self-reliance (Lichtwarck-Aschoff, Kunnen, & van Geert, 2009; Montemayor, 1983).

Friends

Friends become increasingly influential during adolescence. Some parents seem to be concerned about the negative influence of peers; however, it is typical for adolescents to form relationships with others of the same age and with whom they might share beliefs and interests, among other things—this only tends to support what parents encouraged during childhood (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). Adolescents tend to behave more impulsively in front of their peers than do adults. It appears that social pressure may inhibit their ability to “put the brakes on” impulsivity in decision making (Albert, Chein, & Steinberg, 2013). But peers can also have a positive influence, supporting prosocial behaviors (for example, getting good grades or helping others; Roseth, Johnson & Johnson, 2008; Wentzel, McNamara Barry, & Caldwell, 2004).

With the use of smart phones and tablets, these negative and positive influences are often transmitted through digital space. Peer pressure can be exerted through posts on Facebook walls and texts and tweets sent out through mobile devices. To what extent do teens connect through these digital platforms, and what is the nature of their online activity?

SOCIAL MEDIA and psychology

Around 95% of American teens use the Internet, and 80% of them have established identities on social media sites, primarily Facebook. Twitter is less popular, but still used by a substantial 16% (Lenhart et al., 2011). Most teenagers have cell phones, which means they can engage in digital communication virtually 24 hours a day (Lenhart, 2012).

Around 95% of American teens use the Internet, and 80% of them have established identities on social media sites, primarily Facebook. Twitter is less popular, but still used by a substantial 16% (Lenhart et al., 2011). Most teenagers have cell phones, which means they can engage in digital communication virtually 24 hours a day (Lenhart, 2012).

How does all this social media activity affect young people? Networking sites are places where friendships are created and cultivated, but some experts worry that teens place excessive importance on the number of online interactions they have, rather than the depth of those interactions (FoxNews.com, 2013, March 20). Others are concerned that overreliance on digital communication is making teenagers less attuned to facial expressions and social cues normally conveyed in real-life interactions (Stout, 2010, April 30). Social media sites can also serve as staging grounds for negative behaviors like bullying. Just take a look at some data from a survey of several hundred Internet-using teenagers (Lenhart et al., 2011): Approximately 8% say they have been bullied online in the past year; 88% have observed others being “mean or cruel” on a social media site; 25% say their interactions through social media have led to offline arguments; and 8% claim their online conversations have served as the impetus for physical fights.

NETWORK BULLIES AND FRIENDS

But it’s not all bad news. The majority of teens who use social media also say that their interactions on these sites have made them feel better about themselves and more deeply connected to others (Lenhart et al., 2011). Online communities provide teens with a space to explore their identities and interact with people from diverse backgrounds. They serve as platforms for the exchange of ideas and art (sharing music, videos, and blogs), and places for students to study and collaborate on school projects (O’Keeffe, Clarke-Pearson, & Council on Communications and Media, 2011).

Social media is here to stay, and it will continue to impact the socioemotional development of adolescents. The challenge for parents is to find ways to direct this online activity while still recognizing their child’s need for space and autonomy (Yardi & Bruckman, 2011). What steps do you think parents should take to ensure that teenagers are using social media in a positive way?

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

LO 16 Summarize Kohlberg’s levels of moral development.

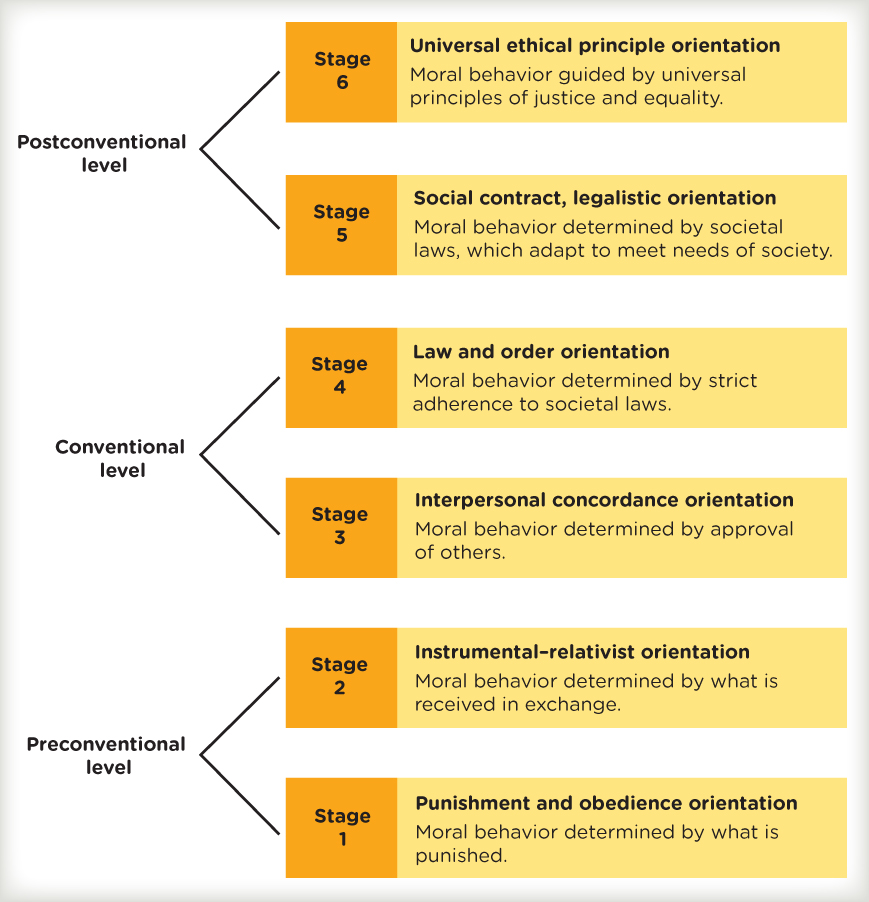

Moral development is another important aspect of socioemotional growth. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–1987), influenced by the work of Piaget, proposed three levels of moral development that occur in sequence over the life span. These levels, which are further divided into two stages, focus on specific changes in beliefs about right and wrong (Figure 8.5.).

Kohlberg used a variety of fictional stories about moral dilemmas to determine the stage of moral reasoning of participants in his studies. The Heinz dilemma is a story about a man named Heinz who was trying to save his critically ill wife. Heinz did not have enough money to buy a drug that could save her, so after trying unsuccessfully to borrow money, he finally decided to steal the drug. The two questions asked of individuals in Kohlberg’s studies were these: “Should the husband have done that? Was it right or wrong?” (Kohlberg, 1981, p. 12). Kohlberg was not really interested in whether his participants thought Heinz should steal the drug or not; instead, the goal was to determine the moral reasoning behind their answers.

Although Kohlberg described moral development as sequential and universal in its progression, he noted that environmental influences and interactions with others (particularly those at a higher level of moral reasoning) support its continued development. Additionally, not everyone progresses through all three levels; an individual may get stuck at an early stage and remain at that level of morality throughout life. Let’s look at these three levels.

Preconventional Moral Reasoning

From the time a toddler or preschooler begins to understand the connection between behavior and its consequences, she can begin to think about moral issues, and make decisions about what is right and wrong. Preconventional moral reasoningusually applies to young children, and it focuses on the consequences of behaviors, both good and bad. For children in Stage 1 (punishment and obedience orientation), “goodness” and “badness” are determined by whether a behavior is punished. Behavior is motivated by showing respect and obedience to avoid being punished. For example, a child decides not to cheat on a test because she is worried about getting caught and then punished. Thus, consequences drive the belief about what is right and wrong. Regarding the Heinz dilemma, a child at this level may say the husband should not steal the drug because he may go to jail if caught. Children in Stage 2 (instrumental–relativist orientation) behave in accordance with a “marketplace” mentality, looking out for their own needs most of the time. The world is seen as an exchange of goods and services, so giving to others does not occur out of loyalty or fairness, but for the hope of reciprocity (“You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours”; Kohlberg & Hersch, 1977).

Conventional Moral Reasoning

At puberty, conventional moral reasoning is used, and determining right and wrong is informed by expectations from society and important others, not simply personal consequences. The emphasis is on conforming to society’s rules and regulations. In Stage 3 (interpersonal concordance orientation), actions that are helpful or please others are considered “good.” Gaining the approval of others (being a “good boy” or “nice girl”) is an important motivator. Faced with the Heinz dilemma, the adolescent might suggest that because society says a husband must take care of his wife, Heinz should steal the drugs so that others won’t think poorly of him. In Stage 4 (law and order orientation), the focus is on rules and social order. Duty and obedience to authorities define what is right. Heinz should not steal because stealing is against the law. Cheating on exams is not right because one is obligated to uphold a student code of conduct (Kohlberg & Hersch, 1977).

Postconventional Moral Reasoning

The third level of Kohlberg’s theory is postconventional moral reasoning. Right and wrong are determined by the individual’s beliefs about morality, which may be inconsistent with society’s rules and regulations. Stage 5 (social contract, legalistic orientation) reasoning suggests that laws should be followed when they are upheld by society as a whole; but, if a law does not exhibit “social utility,” it should be changed to meet the needs of society. In other words, a law and order approach isn’t always morally right. Someone using this type of reasoning might suggest that Heinz should steal the drug because the laws of society fail to consider his unique situation. In Stage 6 (universal ethical principle orientation), moral behavior is determined by universal principles of justice, equality, and respect for human life. An understanding of the “right” thing to do is guided not only by what is universally regarded as right, but also by one’s conscience and personal ethical perspective. With regard to the Heinz dilemma, someone using postconventional moral reasoning would thoughtfully consider all possible options, but ultimately decide human life overrides societal laws.

Criticisms

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the importance of collecting data from a representative sample, whose members’ characteristics closely reflect the population of interest. Kohlberg’s early research included only male participants, but he and others generalized his findings to females. Generalizing from an all-male sample to females in the population may not be justifiable.

Kohlberg’s stage theory of moral development has not been without criticism. Carol Gilligan (1982) leveled a number of serious critiques, suggesting that the theory did not represent women’s moral reasoning. She noted that Kohlberg’s initial studies included only male participants, introducing bias into his research findings. Gilligan suggested that Kohlberg had discounted the importance of caring and responsibility and that his choice of an all-male sample was partially to blame. Another issue with Kohlberg’s theory is that it focuses on the moral reasoning of individuals, and thus is primarily applicable to Western cultures; in more collectivist cultures, the focus is on the group (Endicott et al., 2003). One last concern about Kohlberg’s theory is that we can define and measure moral reasoning, but predicting moral behavior is not always easy. Research that examines moral reasoning and moral behavior indicates that the ability to predict moral behavior is weak at best (Blasi, 1980; Krebs & Denton, 2005).

Emerging Adulthood

When does a child become an adult? There isn’t one particular age that distinctly marks the boundary between a nonadult and an adult. In the United States, the legal age of adulthood is 18 for some activities (voting, military enlistment) and 21 for others (drinking, financial responsibilities). These ages are not consistent across cultures and countries (the legal drinking age in some nations is as young as 16). Many cultures and religions mark the transition into adulthood by ceremonies and rituals (for example, Jewish bar/bat mitzvahs, Australian walkabouts, Christian confirmations, Latin American quinceañeras), starting as early as age 12.

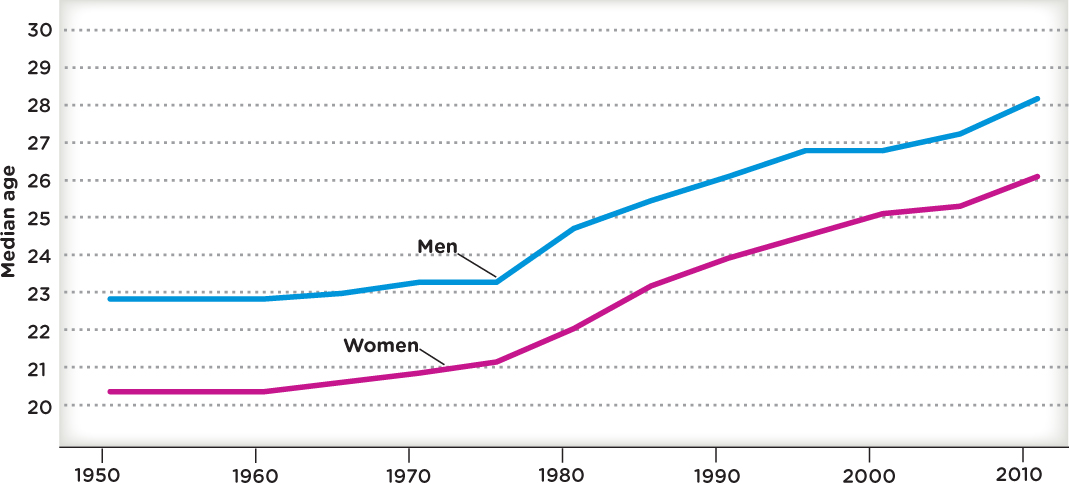

Complicating the demarcation between adolescence and adulthood is the fact that young people in today’s Western societies now remain dependent on their families for longer periods of time. In the past, young people in the United States left their families’ homes much earlier as indicated by marriage data. In 1970, for example, women were marrying for the first time at approximately 21 years of age, and men at 23. In 2010 the age at first marriage was 26 for women, and 28 for men (Arnett, 2000; Elliott, Krivickas, Brault, & Kreider, 2012; Figure 8.6). Psychologists now propose a phase known as emerging adulthood, which is the time of life between 18 and 25 years of age. It is neither adolescence nor early adulthood because it is a period of exploration and opportunity. The emerging adult has neither the permanent responsibilities of adulthood nor the dependency of adolescence. By this time, most adolescent egocentrism has disappeared, which is apparent in intimate relationships and empathy (Elkind, 1967). There are opportunities to seek out loving relationships, education, and new views of the world before settling into the relative permanency of family and career (Arnett, 2000).

The transition from adolescence to young adulthood can be rocky at times. It is by exploring and then committing to their own identities that adolescents often become their own people. Trying out relationships and careers during this period allows them to emerge into adulthood.

show what you know

Question 8.14

1. The physical changes not associated with reproduction, but that become more distinct during adolescence, are known as

- primary sex characteristics.

- secondary sex characteristics.

- menarche.

- puberty.

b. secondary sex characteristics.

Question 8.15

2. Your cousin is almost 14, and she has begun to use deductive reasoning to draw conclusions and critical thinking to support her arguments. Her cognitive development is occurring in Piaget’s

- formal operational stage.

- concrete operational stage.

- ego identity versus role confusion stage.

- instrumental–relativist orientation.

a. formal operational stage.

Question 8.16

3. ________ moral reasoning usually applies to young children, and it focuses on the consequences of behaviors, both good and bad.

Preconventional

Question 8.17

4. “Helicopter” parents pave the way for their children, troubleshooting problems for them, making sure they are successful in every endeavor. How might this type of parenting impact an adolescent in terms of Erikson’s stage of ego identity versus role confusion?

Answers will vary. During the stage of ego identity versus role confusion, an adolescent seeks to define himself through his values, beliefs, and goals. If a helicopter parent has been troubleshooting all of her child’s problems, the child has never had to learn to take care of things for himself. Thus, he may feel helpless and unsure of how to handle a problem that arises. The parent might also have ensured the child was successful in every endeavor, but this too could cause the child to be unable to identify his true strengths, again interfering with the creation of an adult identity.