8.5 Adulthood

A WORK IN PROGREES

At the very beginning of this chapter, we introduced Chloe Ojeah, a 22-year-old community college student caring for two aging grandparents, a 79-year-old grandmother with Alzheimer’s disease and an 85-year-old grandfather recovering from a stroke. Like Jasmine, Chloe is immersed in young adulthood, a time when many people are continuing to forge their identities and lay the groundwork for enduring lifelong relationships. Many of the “Who am I?” type of questions that pop up in adolescence may spill over into this stage of life. Chloe, for example, still hasn’t decided where she stands politically, even though her family clearly leans in a certain direction. Nor has she settled on a religious faith, despite her exposure to at least two different churches. “It’s not a decision I can make with my family,” says Chloe, who wants to find answers on her own terms. “I’m still questioning everything.”

At the very beginning of this chapter, we introduced Chloe Ojeah, a 22-year-old community college student caring for two aging grandparents, a 79-year-old grandmother with Alzheimer’s disease and an 85-year-old grandfather recovering from a stroke. Like Jasmine, Chloe is immersed in young adulthood, a time when many people are continuing to forge their identities and lay the groundwork for enduring lifelong relationships. Many of the “Who am I?” type of questions that pop up in adolescence may spill over into this stage of life. Chloe, for example, still hasn’t decided where she stands politically, even though her family clearly leans in a certain direction. Nor has she settled on a religious faith, despite her exposure to at least two different churches. “It’s not a decision I can make with my family,” says Chloe, who wants to find answers on her own terms. “I’m still questioning everything.”

Like many young adults, Chloe is also beginning to explore her capacity to form deep and loving relationships. Her first serious romantic relationship evolved out of a close friendship she had established while living in Houston. Chloe trusted this boyfriend; she was committed to him; she even loved him, though she wouldn’t say she was “in love” with him. “More than anything,” Chloe insists, “we just enjoyed being around each other.” But spending time together was not much of an option when Chloe relocated to Austin to care for her grandparents. Since they split a little over a year ago, Chloe has remained on good terms with her exboyfriend and his relatives.

As Chloe is just beginning to experience her first meaningful relationships, her grandfather, J. M. Richard, is enjoying his 61st year of married life. When you ask Mr. Richard what he considers his most important achievements, the first thing he says is “marrying my wife.” The last few years have been trying, given her battle with Alzheimer’s disease, but Mr. Richard continues to be deeply committed to her. As he himself offers, “We still love each other.”

Looking back on nearly nine decades of life, Mr. Richard says he feels satisfied: “I am happy with my life, and I am happy with my accomplishments.” His fulfillment does not just stem from marriage and fatherhood. “I am also deep into the Baptist church,” Mr. Richard notes. “I have met most of my spiritual needs with the people of the church and the God I know…. The other thing I have been blessed with up until a year ago was good health.” Before the stroke, Mr. Richard was able to drive his car, which allowed him the freedom to take care of business at his funeral home, maintain the various buildings he rents out to tenants, and oversee building projects on his properties. Now he has nerve damage on the left side of his body, which causes persistent pain. He walks with a cane, is visually impaired, and can no longer drive.

But Mr. Richard hasn’t thrown in the towel. Far from it. With the help of an occupational therapist, he hopes to get behind the wheel again one day. And unlike most people, even those who are half his age, he spends 30 to 40 minutes pedaling on his exercise bike each day. Not only does physical exercise improve his muscle tone and cardiovascular health; it may also help preserve his memory by upping the birthrate of new brain cells (more on this to come). Mr. Richard also maintains a vibrant intellectual life. He is very much involved in the day-to-day activities of the funeral home, talking with his employees on the phone several times a day.

What do you hope to accomplish by the time you reach Mr. Richard’s age? Do you want to have a satisfying marriage and a house full of grandkids? An intense and rewarding career? Perhaps you dream of becoming an accomplished musician, businessperson, or filmmaker. Whatever you want from life, you are most likely to pursue and attain it during the developmental stage known as adulthood. Developmental psychologists have identified various stages of this long period, each corresponding to an approximate age group: early adulthood spans the twenties and thirties, middle adulthood the forties to mid-sixties, and late adulthood everything beyond.

Physical Development

LO 17 Name some of the physical changes that occur across adulthood.

The most obvious signs of aging tend to be physical in nature. Often you can estimate a person’s age just by looking at his hands or facial lines. Let’s get a sense of some of the basic body changes that occur through adulthood.

Early Adulthood

During early adulthood, our sensory systems are sharp, and we are at the height of our muscular and cardiovascular ability. But some systems have already begun their downhill journey. Hearing, for instance, often starts to decline as a result of noise-induced hearing impairment that commences in early adolescence (Niskar et al., 2001). The body is fairly resilient at this stage, but lifestyle choices can have profound health consequences. Heavy drinking, drug use, poor eating habits, and sleep deprivation can make a person look, feel, and function like someone much older.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we described causes for hearing impairment. Damage to the hair cells or the auditory nerve is sensorineural deafness. Conduction hearing impairment results from damage to the eardrum or the middle-ear bones that transmit sound waves. Exposure to loud sounds, such as listening to music through earbuds, may play a role in hearing impairment starting in adolescence.

As we head toward our late thirties, fertility-related changes occur for both men and women. Women experience a 6% reduction in fertility in their late twenties, 14% in their early thirties, and 31% in their late thirties (Menken, Trussell, & Larsen, 1986; Nelson, Telfer, & Anderson, 2013). Men also experience a fertility dip, but it appears to be gradual and results from fewer and poorer quality sperm (Sloter et al., 2006). It is not until age 50 that male fertility declines substantially, however (Kidd, Eskenazi, & Wyrobek, 2001).

Middle Adulthood

In middle adulthood, the skin wrinkles and sags due to loss of collagen and elastin, and skin spots may appear (Bulpitt, Markowe, & Shipley, 2001). Hair starts to turn grey and may fall out. Hearing loss continues and may be exacerbated by exposure to loud noises (Kujawa & Liberman, 2006). Eyesight may decline. The bones weaken. Oh, and did we mention you might shrink as well? All this sounds awful, but do not despair. There are measures you can take to slow the aging process. For example, genes influence height and bone mass, but research suggests we can limit the shrinking process through continued exercise. In one study, researchers followed over 2,000 people for three decades. Everyone in the study got shorter (the average height loss being 4 centimeters, or about 1.6 inches), but those who had engaged in “moderate vigorous aerobic” exercise lost significantly less (Sagiv, Vogelaere, Soudry, & Ehrsam, 2000). The good news is that to maintain your stature and overall physique, you would be wise to participate in lifelong moderate endurance activities such as jogging, walking, and swimming.

For women, middle adulthood is a time of major physical change. Estrogen production decreases, the uterus shrinks, and menstruation no longer follows a regular pattern. This marks the transition toward menopause, the time when ovulation and menstruation cease, and reproduction is no longer possible. Menopausal women can experience hot flashes, sweating, vaginal dryness, and breast tenderness (Newton et al., 2006). These symptoms may sound unpleasant, but many women consider menopause to be a temporary inconvenience, reporting a sense of relief following the cessation of their menstrual periods, as well as increased interest in sexual activity (Etaugh, 2008).

Men experience their own constellation of midlife physical changes, sometimes referred to as male menopause or andropause. Some suggest calling it androgen decline in the aging male, as there is a reduction in testosterone production, not an end to it (Morales, Heaton, & Carson, 2000). Men in middle adulthood may complain of depression, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties, which might be associated with lower testosterone. But research suggests this link between hormones and behavior is evident in only a tiny proportion of aging men (Pines, 2011).

Late Adulthood

Late adulthood, which begins around 65, is also characterized by the decline of many physical and psychological functions. Vision problems, such as cataracts and impaired night vision, are common. Hearing continues on a downhill course, and reaction time increases (Fozard, 1990). The brain processes information more slowly, and brain regions responsible for memory deteriorate (Eckert, Keren, Roberts, Calhoun, & Harris, 2010).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we reported that studies with animals and humans have shown that some areas of the brain are constantly generating new neurons, in a process known as neurogenesis. As we age, this production of new neurons seems to be supported by physical exercise.

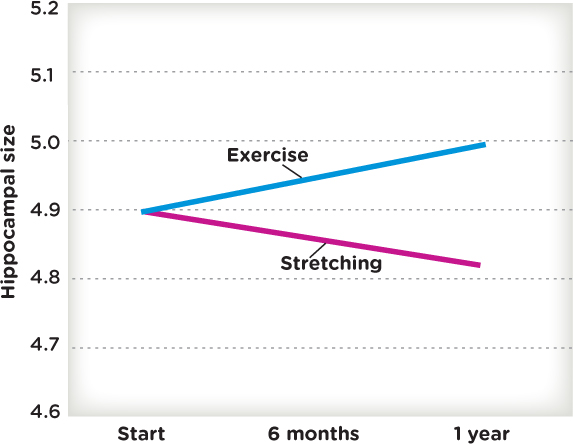

Some of this physical decline is inevitable, but it is possible to age gracefully. Exercise improves bone density and muscle strength, and lowers the risk for cardiovascular disease and obesity. There is even research suggesting that exercise fosters the development of neural networks, helping with the production of new hippocampus nerve cells, which are important in memory (Deslandes et al., 2009; Erickson et al., 2011; see Figure 8.7). Exercise may also reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders of the nervous system (Radak et al., 2010).

Mr. Richard is exceptionally sharp for his age, but his occupational therapist has noticed a decline in some of his cognitive abilities, such as integrating information and reaction time. It is possible, however, that he has actually delayed these processes by staying physically fit. Physical and cognitive development are closely intertwined.

Cognitive Development

What’s going on in the brain as we pass through the various stages of adulthood, and how do those changes affect our ability to function? Let’s explore the cognitive changes of adulthood.

Early Adulthood

LO 18 Identify some of the cognitive changes that occur across adulthood.

Measures of aptitude, such as intelligence tests, indicate that cognitive ability remains stable from early to middle adulthood (Larsen, Hartmann, & Nyborg, 2008), though processing speed begins to decline (Schaie, 1993). Young adults are theoretically in Piaget’s formal operational stage, which means they can think logically and systematically, but some researchers estimate that only 50% of adults ever exhibit formal operational thinking (Arlin, 1975).

Middle and Late Adulthood

Much of the discussion of middle adulthood has focused on decline: declining metabolism, skin elasticity, testosterone, cardiovascular health, and so on. Yet cognitive function does not necessarily decrease during middle adulthood. Longitudinal studies by Schaie and colleagues indicate that decreases in cognitive abilities cannot be reliably measured before 60 (Gerstorf, Ram, Hoppmann, Willis, & Schaie, 2011; Schaie, 1993, 2008). There are some exceptions, however. Midlife is a time when information processing and memory can decline, particularly the ability to remember past events (Ren, Wu, Chan, & Yan, 2013).

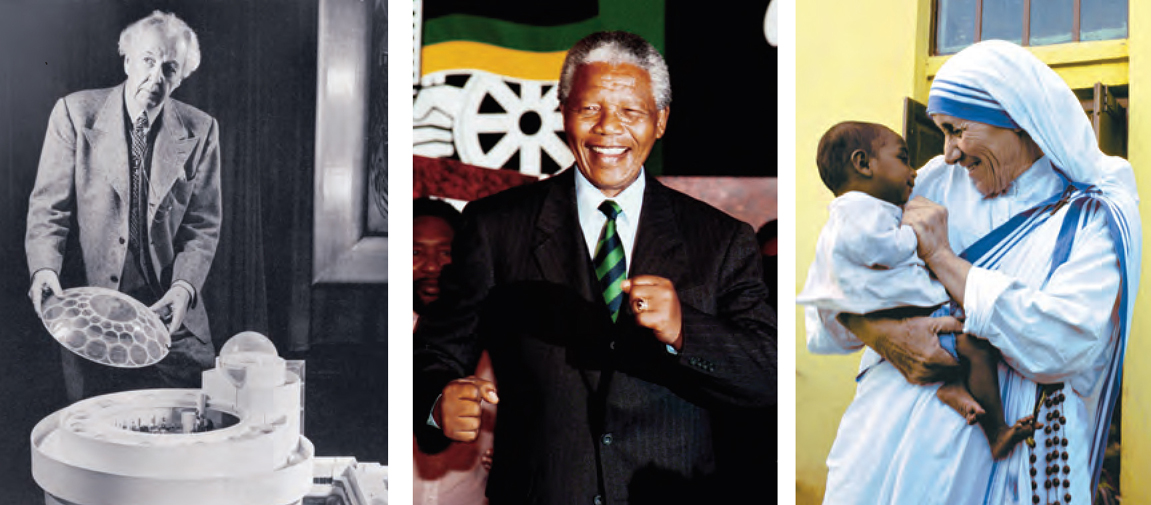

After the age of 70, cognitive decline is more apparent. The Seattle Longitudinal Study has shown that the cognitive performance of today’s 70-year-old participants is similar to the performance of 65-year-olds tested 30 years ago (Gerstorf et al., 2011; Schaie, 1993, 2008). So, turning 65 does not mean it is time to retire, from a cognitive abilities perspective. Processing speed may slow with old age, but older adults are still capable of amazing accomplishments. Frank Lloyd Wright finished designing New York’s Guggenheim Museum when he was 89 years old and Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa when he was 76. Age does not limit us unless we allow it to.

Some types of cognitive skills diminish in old age and others become more refined. Older people may not remember all of their academic knowledge, but their practical abilities seem to grow. Life experiences allow people to develop a more balanced understanding of the world around them, one that only comes with age (Sternberg & Grigorenko, 2005).

When studying cognitive changes across the life span, psychologists frequently describe two types of intelligence: crystallized intelligence, the knowledge we gain through learning and experience, and fluid intelligence, the ability to think in the abstract and create associations among concepts. As we age, the speed with which we learn new material and create associations decreases (von Stumm & Deary, 2012). In one study, researchers examined performance on fluid and crystallized intelligence tasks in adults between the ages of 20 and 78. Crystallized abilities increased with age, whereas fluid abilities increased from 20 to 30 years of age and remained stable until age 50 (Cornelius & Caspi, 1987). Working memory, the active processing component of short-term memory that maintains and manipulates information, also becomes less efficient with age (Nagel et al., 2008; Reuter-Lorenz, 2013).

Earlier we mentioned that physical exercise provides a cognitive boost. The same appears to be true of mental exercises, such as those required for playing a musical instrument (Hanna-Pladdy & MacKay, 2011). That said, there does appear to be a lot of hype surrounding the “use it or lose it” mantra to aging, which suggests that exercising the brain will stop cognitive decline. Use it or lose it might be a slight overstatement when it comes to maintaining cognitive function (Salthouse, 2006). Although there are clear advantages to doing crossword puzzles and reading the newspaper, inconclusive evidence exists to support the notion that this activity has the same effect it would have on a child, for example. When older adults exercise their brains in a particular domain (for example, playing a musical instrument or using Wii Big Brain Academy software), the results do not necessarily transfer to other general abilities, such as cognitive and perceptual information processing (Ackerman, Kanfer, & Calderwood, 2010). Specifically, tasks that help to train working memory may (or may not) improve fluid intelligence, even into older age (Nisbett et al., 2012). But, research suggests that people who continue to work, both physically and mentally, and remain in good physical shape are less likely to experience significant cognitive decline (Rohwedder & Willis, 2010). Thus, if your goal is to maintain a sharp mind as you age, don’t just increase your Sudoku playing or your reading time. You need to maintain a balanced approach incorporating a broad range of activities and interests.

CONNECTIONS

Here, we are reminded of an issue presented in Chapter 1: We must be careful not to equate correlation with causation. In this case, if you experience a decline in cognitive ability, you are less likely to work. Thus, it is the cognitive decline that would lead to the lack of work.

Socioemotional Development: Early, Middle, and Late Adulthood

Socioemotional development does not always occur in a neat, stepwise fashion. Some of us become parents as teenagers, others not until our forties. This next section describes a host of social and emotional transformations that typically occur during adulthood.

Erikson and Adulthood

LO 19 Explain some of the socioemotional changes that occur across adulthood.

Earlier we described Erikson’s approach to explaining socioemotional development from infancy through adolescence, noting that unsuccessful resolution of prior stages has implications for the stages that follow (see TABLE 8.2). During young adulthood (twenties to forties), people are challenged by intimacy versus isolation. Young adults tend to focus on creating meaningful, deep relationships, and failing at this endeavor may lead to a life of isolation, Erikson proposed. He also believed that we are unable to form these relationships if identity has not been clearly established in the identity versus role confusion of adolescence.

Moving into middle adulthood (forties to mid-sixties), we face the crisis of generativity versus stagnation. Positive resolution of this stage includes feeling like you have made a real impact on the next generation, through parenting, community involvement, or work that is valuable and significant. Those who do not have a positive resolution of this stage face stagnation, characterized by boredom, conceit, and selfishness.

In late adulthood, we look back on life and evaluate how we have done, a crisis of integrity versus despair (mid-sixties and older). If previous stages have resulted in positive resolutions, we feel a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. A negative resolution of this stage indicates that we have regrets and dissatisfaction.

Before we further explore socioemotional development in adulthood, we must note that Erikson’s theory, though very important in the field of developmental psychology, has provided more framework than substantive research findings. His theory was based on case studies, with limited supporting research. In addition, the developmental tasks of Erikson’s stages might not be limited to the particular time frame proposed. For example, creating an adult identity is not limited to adolescence, as this stage may resurface at any point in adulthood (Schwartz, 2001).

Romance and Relationships

Young adulthood is a time when romantic relationships move in a new direction. The focus shifts away from fun-filled first experiences with sex and love to deeper connections. For many people, the twenties are a transition period between the “here and now” type of relationships of adolescence to the serious, long-term partnerships of adulthood (Arnett, 2000). Some of these relationships lead to what many people consider the most challenging, yet rewarding, role in life: parenthood.

Parenting

LO 20 Summarize the four types of parenting proposed by Baumrind.

Do you ever find yourself watching parent–child interactions at the store? You likely have noticed a vast spectrum of child-rearing approaches. Diana Baumrind (1966, 1971) has been studying parenting for over four decades, and her work has led to the identification of four parenting behavioral styles. These styles seem to be stable across situations, and are distinguished by levels of warmth, responsiveness, and control (Maccoby & Martin, 1983).

Parents who insist on rigid boundaries, show little warmth, and expect high control exhibit authoritarian parenting. They want things done in a certain way, no questions asked. “Because I said so” is a common justification used by such parents. Authoritarian parents are extremely strict and demonstrate poor communication skills with their children. Their kids, in turn, tend to have lower self-assurance and autonomy, and experience more problems in social settings (Baumrind, 1991).

Authoritative parenting may sound similar to authoritarian parenting, but it is very different. Parents who practice authoritative parenting set high expectations, demonstrate a warm attitude, and are responsive to their children’s needs. Being supported and respected, children of authoritative parents are quite responsive to their parents’ expectations. They also tend to be self-assured, independent, responsible, and friendly (Baumrind, 1991).

With permissive parenting, the parent demands little of the child and imposes few limitations. These parents are very warm but often make next to no effort to control their children. Ultimately, their children tend to lack self-control, act impulsively, and show no respect for boundaries.

Uninvolved parenting describes parents who seem indifferent to their children. Emotionally detached, these parents exhibit minimal warmth and devote little time to their children, although they do provide for their children’s basic needs. Children raised by uninvolved parents tend to exhibit behavioral problems, poor academic performance, and immaturity (Baumrind, 1991).

Keep in mind that the great majority of research on these parenting styles has been conducted in the United States, which should make us wonder how applicable these categories are in other countries and cultures (Grusec, Goodnow, & Kuczynski, 2000). Other factors to consider include the home environment, the child’s personality and development, and the unique parent–child relationship. A child who is irritable will react to an authoritarian parent’s restrictions in a different way than one who is easygoing, for example (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994).

Parenting is incredibly hard work. Physically exhausting, emotionally trying, and sometimes plain exasperating, parenting can make you feel like you are aging at the speed of light, but some evidence suggests it’s quite the opposite.

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Changing Social Roles Can Reverse Aging

Old bees that start caring for young ones gain cognitive power.

How many mothers have looked at their children and thought, “Ah, they keep me young”? Now we know how right they are.

Caring for the young may delay—and in some cases, even reverse—multiple negative effects of aging in the brain. Gro Amdam, who studies aging in bees at Arizona State University, observed tremendous improvements in cognition among older bees that turn their attention back to nursing. She has reason to believe that changes in social behavior could shave years off the human brain as well.

When bees age, their duties switch from taking care of the brood to foraging outside the hive. The transition is followed by a swift physical and cognitive decline. Amdam removed young bees from their hives, which tricked the older bees into returning to their caretaker posts. Then she tested their ability to learn new tasks. A majority reverted to their former cognitive prowess, according to results published in the journal Experimental Gerontology. “What we saw was the complete reversal of the dementia in these bees. They were performing exactly as well as young bees,” Amdam says.

The ones that improved had higher levels of the anti-oxidant PRX6 in their brain, a protein that exists in humans and is thought to protect against neurodegenerative diseases. Amdam’s theory is that when older individuals participate in tasks typically handled by a younger generation—whether in a hive or in our own society—antioxidant levels increase in the brain and turn back the clock. Youth, it turns out, may be infectious after all. Morgen Peck. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2012 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

And so, it seems, aging does not always go hand-in-hand with cognitive decline. The same could be said of wisdom, the ability to use reasoning to tackle life’s challenges (Kross & Grossmann, 2012) and make better decisions (Worthy, Gorlick, Pacheco, Schnyer, & Maddox, 2011). Wisdom grows as we accumulate a vast amount of experience (Ardelt, 2010), but experience does not always correlate with age. Chloe, who is only 22, and Jasmine, 31, may be young, but they are also quite wise.

Growing Old With Grace

When many people think of growing older, the image that surfaces is of a frail old woman (or man) sitting in a bathrobe and staring out the window, unable to care for herself. This stereotype is not accurate. As of 2000, fewer than 5% of Americans older than 65 lived in a nursing home (Hetzel & Smith, 2001). Most older adults in the United States enjoy active, healthy, independent lives. They are involved in their communities, faith, and social lives, and contrary to popular belief—a large number have active sex lives (Lindau et al., 2007). Researchers have discovered that happiness generally increases with age (Jeste et al., 2013). Positive emotions become more frequent than negative ones, and emotional stability increases, meaning that we experience fewer extreme emotional swings (Carstensen et al., 2011). Stress and anger begin to diminish in early adulthood, and worry becomes less apparent after age 50 (Stone, Schwartz, Broderick, & Deaton, 2010).

Older people might feel happy because they no longer care about proving themselves in the world, they are pleased with the outcome of their lives, or they have developed a strong sense of emotional equilibrium (Jeste et al., 2012). Research suggests that older adults who are healthy, independent, and engaged in social activities also report being happy, and there is some evidence that this increased happiness may result in a longer life (Oerlemans, Bakker, & Veenhoven, 2011). Americans are now living longer than ever, with the average life expectancy of women being 81.1 years and men 76.3 years (Hoyert & Xu, 2012). Could happiness be one of the factors driving this increase in life span?

Death and Dying

We have spent this entire chapter discussing life. Many of the stages and changes described occur at different times for different people, sometimes overlapping, other times skipped altogether. When it comes to life, nothing is certain—except, of course, the arrival of death.

LO 21 Describe how Kübler-Ross explained the stages of death.

Apart from sex, few topics are as difficult to address as death and dying. Psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (2009) opened the discussion in the early 1960s, while working with people facing the end of life. She found they experienced similar reactions when faced with the news that their deaths were imminent: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. These stages, Kübler-Ross suggested, are coping mechanisms for dealing with what is to come.

- Denial: In the denial stage, a person may react to the news with shock and disbelief, perhaps even suggesting the doctors are wrong. Unable to accept the diagnosis, he may seek other medical advice.

- Anger: A dying person may feel anger toward others who are healthy, or toward the doctor who does not have the cure. Why me? she may wonder, projecting her anger and irritability in a seemingly random fashion.

- Bargaining: This stage may involve negotiating with God, doctors, or other powerful figures for a way out. Usually, this involves some sort of time frame: Let me live to see my firstborn get married, or Just give me one more month to get my finances in order.

- Depression: There comes a point when a dying person can no longer ignore the inevitable. Depression may be due to the symptoms of the patient’s actual illness, but it can also result from the overwhelming sense of loss—the loss of the future.

- Acceptance: Eventually, a dying person accepts the finality of his predicament; death is inevitable, and it is coming soon. This stage can deeply impact family and close friends, who, in some respects, may need more support than the person who is dying. According to one oncologist, the timing of acceptance is quite variable. For some people, it occurs in the final moments before death; for others, soon after they learn there is no chance of recovery from their illness (Lyckholm, 2004).

Kübler-Ross was instrumental in bringing attention to the importance of attending to the dying person (Charlton & Verghese, 2010; Kastenbaum & Costa, 1977). The stages she proposed provide a valuable framework for understanding death, but keep in mind that every person responds to death in a unique way. For some people, the stages are overlapping; others don’t experience the stages at all (Schneidman, 1973). We should also note that there is little research supporting the validity of stages of death, and that the theory arose in a Western cultural context. Evidence suggests that people from other backgrounds may view death and dying from very different perspectives.

across the WORLD

Death in Different Cultures

What does death mean to you? Some of us believe death marks the beginning of a peaceful afterlife. Others see it as a crossing over from one life to another. Still others believe death is like turning off the lights; once you’re gone, it’s all over.

What does death mean to you? Some of us believe death marks the beginning of a peaceful afterlife. Others see it as a crossing over from one life to another. Still others believe death is like turning off the lights; once you’re gone, it’s all over.

Views of death are very much related to religion and culture. A common belief among Indian Hindus, for example, is that one should spend a lifetime preparing for a “good death” (su-mrtyu). Often this means dying in old age, after conflicts have been put to rest, family matters settled, and farewells said. To prepare a loved one for a good death, relatives place the person on the floor at home (or on the banks of the Ganges River, if possible) and give her water from the hallowed Ganges. If these and other rituals are not carried out, the dead person’s soul may be trapped and the family suffers the consequences: nightmares, infertility, and other forms of misfortune (Firth, 2005). Imagine a psychologist trying to assist grieving relatives without any knowledge of these beliefs and traditions.

Every culture has its own collection of ideas about death. In Japan and other parts of East Asia, families often make medical decisions for the dying person (Matsumura et al., 2002). They may avoid using words like “cancer” to shield them from the bad news, believing this knowledge may cause them to lose hope and deteriorate further (Koenig & Gates-Williams, 1995; Searight & Gafford, 2005). Yet, healthy East Asians are more likely than European Americans to engage in and enjoy life when reminded of the imminence of death (Ma-Kellams & Blascovich, 2012).

EVERY CULTURE HAS ITS OWN IDEAS ABOUT DEATH.

Interesting as these findings may be, remember they are only cultural trends. Like any developmental step, the experience of death is shaped by countless social, psychological, and biological factors.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

Do you wonder what became of Jasmine Mitchell and Chloe Ojeah? Both women continue to stay busy, pursuing careers and looking after their families. Chloe is still in school and caring for her grandparents. She switched her academic focus to sign language and hopes to become an interpreter for the deaf community, though she is also contemplating a career in phlebotomy, the medical specialty of drawing blood. Jasmine graduated from Waubonsee Community College and is now studying psychology at Aurora University. Eddie is busy playing soccer and learning to read, while Jocelyn juggles schoolwork, basketball, and driver’s education. Stay tuned for further developments in the next edition!

show what you know

Question 8.18

1. Physical changes during middle adulthood include hearing loss, declining eyesight, and loss of height. Research suggests which of the following can help limit the shrinking process?

- physical exercise

- elastin

- andropause

- collagen

a. physical exercise

Question 8.19

2. As we age, our ________ intelligence, or ability to think abstractly, decreases, but our knowledge gained through experience, our ________ intelligence, increases.

fluid; crystallized

Question 8.20

3. When faced with death, a person can go through five stages. The final stage is ________, and sometimes family members need more support during this stage than the dying person.

- denial

- anger

- bargaining

- acceptance

d. acceptance

Question 8.21

4. An aging relative in his mid-seventies is looking back on his life and evaluating what he has accomplished. He feels satisfied with his work, family, and friends. Erikson would say that he has succeeded in solving the crisis of ________ versus ________.

integrity; despair

Question 8.22

5. Describe the four types of parenting proposed by Baumrind. Think of your two closest friends in high school. Citing specific examples, identify the type of parenting their parents used.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following definitions. Parents who insist on rigid boundaries, show little warmth, and expect high control exhibit authoritarian parenting. Parents who practice authoritative parenting set high expectations, demonstrate a warm attitude, and are highly responsive to their children’s needs. Parents who place very few demands on their children and do not set many limitations exhibit permissive parenting. Uninvolved parenting refers to parents who seem to be indifferent, are emotionally uninvolved with their children, and do not exhibit warmth, although they provide for their children’s basic needs.