9.2 Theories of Motivation

GOOD BYE, SOMALIA

Somalia was not a safe place in 1991. The groups that orchestrated the revolution began warring among themselves, and the country plunged into bloody chaos. Over 20,000 innocent people were killed in the crossfire (Gassmann, 1991, December 21). A famine and food crisis ensued, which, in addition to the ongoing fighting, led to 240,000 to 280,000 deaths within the next 2 years (Gundel, 2003). It is easy to understand why Mohamed’s parents, or anyone, would want to remove their family from Somalia during this period. Faced with a life-or-death situation, they were motivated by what you might call a “survival” instinct.

Somalia was not a safe place in 1991. The groups that orchestrated the revolution began warring among themselves, and the country plunged into bloody chaos. Over 20,000 innocent people were killed in the crossfire (Gassmann, 1991, December 21). A famine and food crisis ensued, which, in addition to the ongoing fighting, led to 240,000 to 280,000 deaths within the next 2 years (Gundel, 2003). It is easy to understand why Mohamed’s parents, or anyone, would want to remove their family from Somalia during this period. Faced with a life-or-death situation, they were motivated by what you might call a “survival” instinct.

Instinct. You hear this word used all the time in everyday conversation: “Trust your instincts,” people say in times of uncertainty. “That fighter has a killer instinct,” a sports commentator remarks during a boxing match. But what exactly are instincts, and do humans really have them?

Instinct Theory

LO 3 Summarize instinct theory.

Instincts form the basis of one of the earliest theories of motivation. Scientists studying animal behaviors were among the first to observe instincts. These complex behaviors are fixed, unlearned, and consistent within a species. Motivated by instincts, South American ovenbirds construct elaborate cavelike nests, and sea turtles swim back hundreds of miles to feeding grounds they visited years earlier (Broderick, Coyne, Fuller, Glen, & Godley, 2007). No one teaches the birds to build their nests or the turtles to retrace migratory routes; through evolution, these behaviors appear to be etched into their genetic make-up.

Inspired in part by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, early theorists proposed that humans also have a variety of instincts (McDougall, 1912). American psychologist William James (1890/1983) suggested we could explain some human behavior through instincts such as attachment and cleanliness. At the height of instinct theory’s popularity, several thousand human “instincts” had been named (for example, curiosity, flight, and aggressiveness; Bernard, 1926; Kuo, 1921). Yet there was little evidence they were true instincts—that is, complex behaviors that are fixed, unlearned, and consistent within a species. Only a handful of human behaviors might be considered instincts, such as rooting behavior in newborn infants (Chapter 8). But even these are more related to reflexes than a complex activity like nest building.

Although instinct theory itself faded into the background, some of its themes are apparent in the evolutionary perspective. A substantial body of research suggests that evolutionary forces influence human behavior. For example, emotional responses, such as fear of snakes, heights, and spiders, may have evolved to protect us from danger (Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Neiderhiser, 2013). But these fears are not instincts, because they are not universal. Not everyone is afraid of snakes and spiders; some of us have learned to fear (or not fear) them through experience. When trying to pin down the motivation for behavior, it is difficult to determine the relative contributions of learning (nurture) and innate factors (nature) such as instinct (Deckers, 2005).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we presented the evolutionary perspective, which suggests humans have evolved adaptive traits through natural selection. Behaviors that improve the chances of survival and reproduction are most likely to be passed along to offspring, whereas less adaptive behaviors decrease in frequency. Humans do appear to have innate responses that have been shaped by our ancestors’ behaviors.

FOUR YEARS IN KENYA

After fleeing the bullet-riddled city of Mogadishu, Mohamed and his family made their way across the border into the neighboring country of Kenya, where they lived for about 4 years. Mohamed considers himself one of the “more fortunate ones.” Not only was he lucky to get out of the war zone alive—“A lot of people lost their lives trying to flee,” he notes—but he also had a decent place to go. Many Somalis had no choice but to settle in squalid, overcrowded refugee camps. Mohamed’s family had the means to rent a small apartment in the capital city of Nairobi.

After fleeing the bullet-riddled city of Mogadishu, Mohamed and his family made their way across the border into the neighboring country of Kenya, where they lived for about 4 years. Mohamed considers himself one of the “more fortunate ones.” Not only was he lucky to get out of the war zone alive—“A lot of people lost their lives trying to flee,” he notes—but he also had a decent place to go. Many Somalis had no choice but to settle in squalid, overcrowded refugee camps. Mohamed’s family had the means to rent a small apartment in the capital city of Nairobi.

Being an outsider in Kenya was not easy, however. Career opportunities were scarce. Back in Somalia, Mohamed’s father had earned a solid living constructing buildings, and his mother had been a successful entrepreneur selling homemade food from their house. In Kenya, neither parent could find employment. They had no choice but to live off “remittances,” or money sent from family members outside of Africa, and relying on other people was not their style. “You’re waiting on other people to feed you,” Mohamed says, “and [my father] didn’t like that.”

Daily life presented its fair share of challenges, too. Mohamed’s diet was painfully monotonous, with most meals centering around ugali, a dense gruel made of corn or millet flour—similar to oatmeal, but harder in consistency. At times, the apartment building lost electricity for weeks, or water stopped flowing from faucets. During water shortages, the whole family would carry empty buckets and tubs to a nearby army base and ask for water. Despite these difficulties, Mohamed never went hungry or thirsty. His basic physiological needs were usually met.

Mohamed: How have your childhood experiences impacted you as an adult?

Drive-Reduction Theory

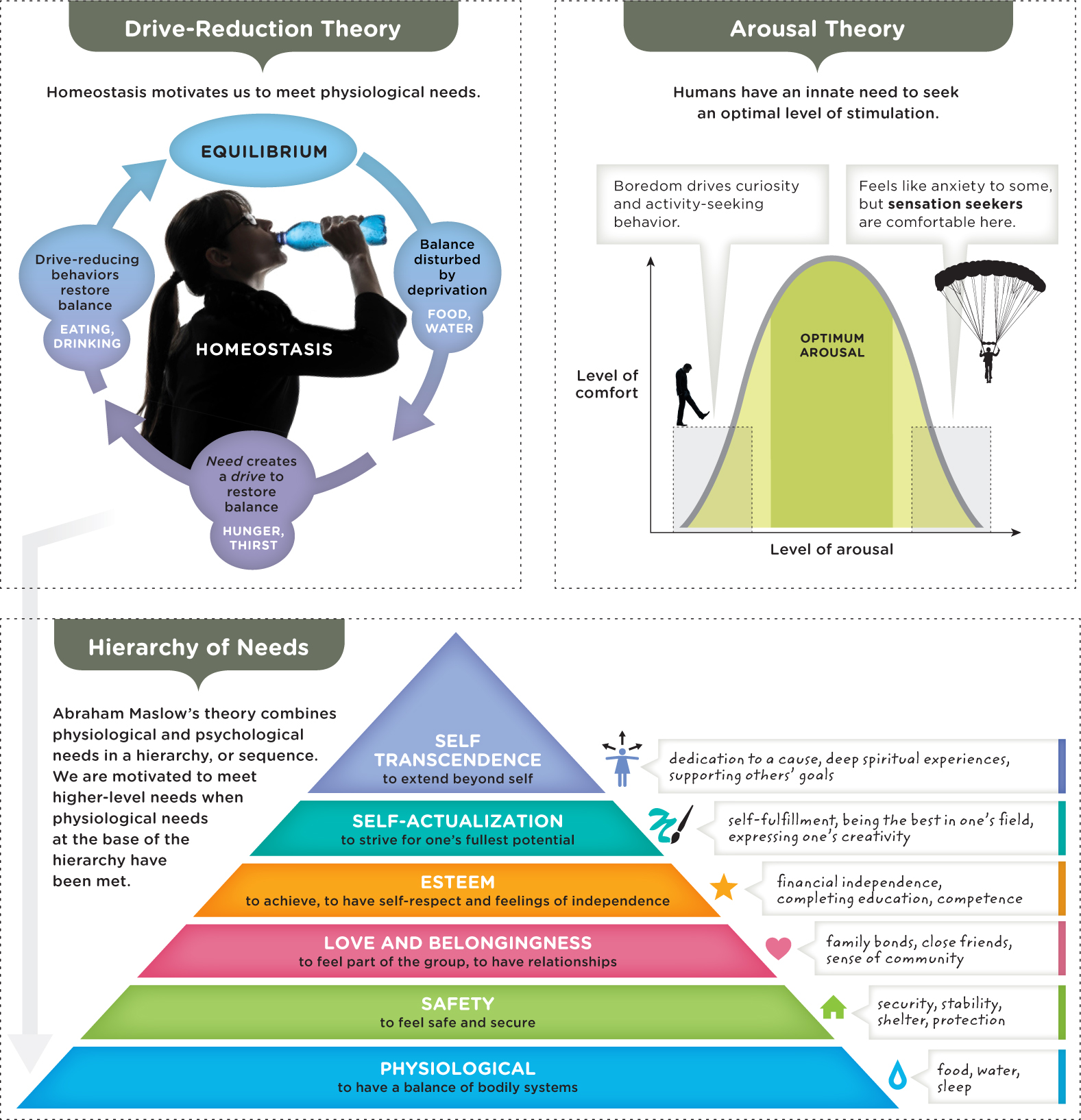

Humans and animals have basic physiological needs or requirements that must be maintained at some baseline or constant state to ensure continued existence. Homeostasis refers to the way in which our bodies maintain these constant states through internal controls. In order to survive, there is a continuous monitoring of required levels of oxygen, fluid, nutrients, and so on. If these fall below desired or necessary levels, an urge to restore equilibrium surfaces. And this urge motivates us to act.

LO 4 Describe drive-reduction theory and explain how it relates to motivation.

The drive-reduction theory of motivation proposes that this biological balancing act is the basis for motivation (Hull, 1952). According to this theory, behaviors are driven by the need to maintain homeostasis—that is, to fulfill basic biological needs for nutrients, fluids, oxygen, and so on (see Infographic 9.1). If a need is not fulfilled, this creates a drive, or state of tension, that pushes us or motivates behaviors to meet the need. The urges to eat, drink, sleep, seek comfort, or have sex are associated with physiological needs. Once a need is satisfied, the drive is reduced, at least temporarily, because this is an ongoing process, as the need inevitably returns. For example, when the behavior (let’s say eating) stops, the deprivation of something (such as food) causes the need to increase again.

Let’s look at another concrete example of drive reduction. Imagine you visit a mountainous area 6,500 feet above sea level, which puts a strain on breathing. While jogging, you find yourself gasping for air because your oxygen levels have dropped. Motivated by the need to maintain homeostasis, you stop what you are doing until your oxygen levels return to normal. Having an unfulfilled need (not enough oxygen) creates a drive (state of tension) that pushes you to modify your behavior in order to restore homeostasis (you stop and breathe deeply, allowing your blood oxygen levels to return to a normal level). The drive-reduction theory helps us understand how physiological needs can be motivators, but it is less useful for explaining why we climb mountains, go to college, or drive cars too fast.

Arousal Theory

Mohamed arrived in America when he was 6 years old. Stepping off the plane in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis/St. Paul) was quite a shock for a young boy who had lived most of his childhood in the crowded, pavement-covered city of Nairobi. “It was really strange to me,” Mohamed says. “At that time, I hadn’t really seen a place that had space.” How odd it was to see patches of green grass in front of every house. “Everything looked like it sparkled.”

New places, people, and experiences can be frightening. They can also be delightfully exhilarating. Humans are fascinated by novelty, and you see evidence of this innate curiosity in the earliest stages of life. Babies grab, suck, and climb on just about everything they can get their hands on, including (much to the horror of their parents) dangerous electrical devices. Ignoring the most forceful parental warnings (Do NOT touch that hot plate!), many toddlers still reach out and touch extremely hot cookware or recklessly leap between pieces of furniture. But mind you, children are not the only ones seeking new experiences. Grown men and women will pay hundreds of dollars to parachute out of airplanes or float over jagged mountains in hot-air balloons. They also spend hours tooling around Web sites like Wikipedia and YouTube—just to learn about new things. Why engage in activities that have little, if anything, to do with satisfying basic biological needs? Humans are driven by other types of urges, including the apparent need for stimulation.

But we are not the only ones hungry for new experiences. Our primate cousins are also inquisitive, which suggests that they too have an innate need for enrichment and sensory stimulation. Researchers studying monkeys, for example, report that they attempt to open latches even without extrinsic motivation; apparently, their curiosity motivates their behavior (Butler, 1960; Harlow, Harlow, & Meyer, 1950).

LO 5 Explain how arousal theory relates to motivation.

According to arousal theory, humans (and perhaps other primates) seek an optimal level of arousal, as not all motivation stems from physical needs. Arousal, or engagement in the world, can be a product of anxiety, surprise, excitement, interest, fear, and many other emotions. Have you ever had an unexplained urge to make simple changes to your daily routines, like taking a new route to work, preparing your morning eggs differently, or adding new clothes to your wardrobe? These behaviors may stem from your need to increase arousal, as optimal arousal is a personal or subjective matter that is not the same for everyone (Infographic 9.1). Zuckerman (1979, 1994) found evidence that some people are sensation seekers; that is, they appear to seek activities that increase arousal. Popularly known as “adrenaline junkies,” these individuals relish activities like cliff diving, racing motorcycles, and watching horror movies. High sensation seeking is not necessarily a bad thing, as it may be associated with a higher tolerance for stressful events (Roberti, 2004).

We have discussed motivation in the context of instinct, drive reduction, and arousal. Now let’s explore how motivation relates to satisfying a broad spectrum of biological and psychological needs.

Needs and More Needs: Maslow’s Hierarchy

LO 6 Outline Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed Maslow and his involvement in humanistic psychology. The humanists suggest that people are inclined to grow and change for the better, and this perspective is apparent in the hierarchy of needs. Humans are motivated by the universal tendency to move up the hierarchy and meet needs toward the top.

Have you ever been in a car accident, lived through a hurricane, or witnessed a violent crime? At the time, you probably were not thinking about what show you were going to watch on television that night. When physical safety is threatened, everything else tends to take a backseat. This is one of the themes underlying the hierarchy of needs theory of motivation proposed by Abraham Maslow (1908–1970), a leading figure in the humanistic movement. Maslow organized human needs into a hierarchy of biological and psychological needs, often depicted as a pyramid (Infographic 9.1). The needs in the hierarchy are considered universal and are ordered according to the strength of their associated drives, with the most critical needs at the bottom. Hunger and thirst, for example, are situated at the base of the hierarchy, and generally take precedence over higher-level needs (that is, these higher-level needs are ignored for the time being).

INFOGRAPHIC 9.1: Theories of Motivation

Motivational forces drive our behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. Psychologists have proposed different theories addressing the needs that create these drives within us. Let’s look at the three most prominent theories of motivation. Some theories, like drive-reduction theory, best explain motivation related to physiological needs. Other theories focus on psychological needs, such as the need for an optimum level of stimulation, as described in arousal theory. In his hierarchy of needs, Abraham Maslow combined various drives and proposed that we are motivated to meet some needs before others.

Physiological Needs

Physiological needs include the requirements for food, water, sleep, and an overall balance of bodily systems. If a life-sustaining need such as fluid intake goes unsatisfied, other needs are placed on hold and the person is motivated to find ways to satisfy it. For example, the Chilean miners introduced in Chapter 1 spent weeks trapped underground with no clean drinking water. To quench their thirst, they were willing to drink oil-contaminated water (and urine, in the case of one man).

Safety Needs

For most North Americans, basic physiological needs are “relatively well gratified” (Maslow, 1943), and thus Maslow would suggest their behavior is motivated by the next higher level of needs in the hierarchy: safety needs. But how you define safety depends on the circumstances of your life. If you were living in Mogadishu during the 1991 revolution (and many times subsequent to that period), staying safe might have involved dodging bullets and artillery fire. For those currently living in Somalia, safety includes having access to safe drinking water and disease-preventing vaccines. Most people living in America do not have to worry about access to clean water or routine vaccinations. Here, safety is more likely equated with the need for predictability and order: having a steady job, a home in a safe neighborhood, health insurance, and living in a country with a stable economy. What does safety mean for you?

Love and Belongingness Needs

If safety needs are being met, then people will be motivated by the love and belongingness needs. Maslow suggested this includes the need to avoid loneliness, to feel like part of a group, and to maintain affectionate relationships. Except for a rare run-in with neighborhood bullies, Mohamed enjoyed a fairly secure existence in Minnesota. His need for safety was met, so he was motivated at this next level of the hierarchy. In addition to cultivating deep family bonds, Mohamed befriended two boys he met in middle school, one who had emigrated from Bangladesh and the other a first-generation Mexican American. Not only could these boys relate to the immigrant experience; they also shared Mohamed’s academic motivation. “They both are people who value education over anything else,” Mohamed says. The three pals all ended up going to the University of Minnesota, and they remain inseparable.

We all want to belong, and failing to meet this need has significant consequences. People who feel disconnected or excluded may demonstrate less prosocial behavior (Twenge, Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Bartels, 2007) and behave more aggressively and less cooperatively, which only tends to intensify their struggle for social acceptance (DeWall, Baumeister, & Vohs, 2008).

Esteem Needs

If the first three levels of needs are being met, then the individual might be motivated by esteem needs, including the need to be respected by others, to achieve, and to have self-respect, self-confidence, and feelings of independence. Cultivating and fulfilling these needs foster a sense of confidence and self-worth, both qualities that Mohamed seems to possess. It was early in life that Mohamed began doing things for himself. His parents may have been there to encourage him, but they could not hold his hand when it came to tasks demanding proficiency in English—like filling out employment applications. But Mohamed did just fine on his own, landing his first job at a nonprofit student loan company just after ninth grade, and performing so well that the company employed him throughout college. Mohamed, it appears, began meeting esteem needs very early on.

Self-Actualization

Even with the above-mentioned needs actively being met, Maslow suggested that the need for self-actualization would motivate someone “to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming” (Maslow, 1943, p. 382). Self-actualization is the need to reach one’s fullest potential. Some will meet this need by being the best possible parent, others will strive to be the best artist or musician. This need is at the heart of the humanistic movement: Self-actualization represents the human tendency toward growth and self-discovery (Chapter 11). For Mohamed, it means being an exceptional scholar, employee, and father. He also dreams of bringing together Somalis from all around the world through his social networking/media company, Calaacal. The site is just getting off the ground, but it has great potential. Perhaps one day Calaacal will facilitate a grassroots movement to restore peace, unity, and prosperity to Somalia.

Self-Transcendence

Toward the end of his life, Maslow proposed an additional need: that for self-transcendence. This need motivates us to go beyond our own needs and feel outward connections through “peak experiences” of ecstasy and awe. Fulfilling this need might mean devoting oneself to a humanitarian cause, pursuing a lofty ideal, or achieving spiritual enlightenment. If you walked into Mohamed’s room, you would see a huge poster that says, “Live a simple life so others can simply live.” What this means, explains Mohamed, is that you should do the best you can in life, but also strive to allow others to do the same. “It’s balancing your life so that you’re always doing the most positive good,” he says. As president of the University of Min-nesota’s Somali Student Association, Mohamed put this slogan to work, organizing activities to support Somali students, and arranging cultural awareness events at the university and in the greater Twin City communities.

Exceptions To The Rule

Maslow’s hierarchy provides suggestions for the order of needs, but this sequence is not set in stone. In some cases, people abandon physiological needs in order to meet a self-actualization need—going on a hunger strike or giving up material possessions, for example. During the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, Mohamed refrains from drinking or eating from dawn to dusk—not an easy task during August in Minnesota, where the sun rises at about 6:00 a.m. and sets well after 8:00 p.m. The practice of fasting, which also occurs in Christianity, Hinduism, and Judaism, illustrates how basic physiological needs (eating and drinking) can temporarily be placed on hold for a greater purpose (religion).

Safety is another basic need often relegated in the pursuit of something more transcendent. Just think of all the soldiers who have given their lives fighting for causes like freedom and social justice. Somali parents living in a war zone and battling hunger may neglect their own basic needs to ensure their children’s well-being, thus fulfilling higher needs such as love and esteem.

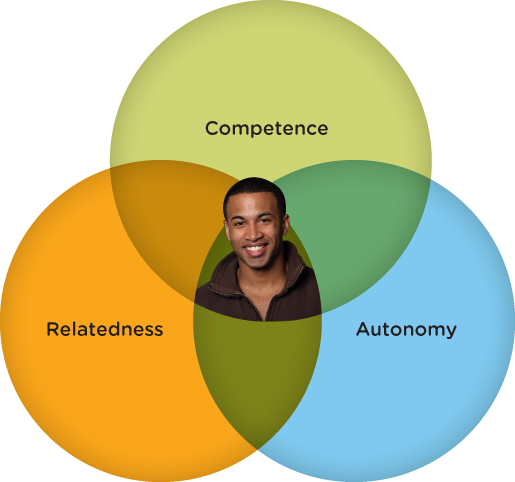

Self-Determination Theory

LO 7 Explain how self-determination theory relates to motivation.

Building on the ideas of both Maslow and Erik Erikson, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan (2008) proposed the self-determination theory (SDT), which suggests that humans are born with three universal, fundamental needs that are always driving us in the direction of optimal functioning: competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Figure 9.1; Stone, Deci, & Ryan, 2009). Competence represents the need to reach our goals through successful mastery of day-to-day responsibilities. Relatedness is the need to create meaningful and lasting relationships. And autonomy means managing one’s behavior to reach personal goals. Self-determination theory does not focus on overcoming one’s shortcomings, but on moving in a positive direction.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 8, we introduced Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, which suggests that stages of development are marked by a task or emotional crisis. These crises often touch on issues of competence, relatedness, and autonomy.

Need For Achievement

In the early 1930s, Henry Murray proposed that humans are motivated by 20 fundamental human needs, one of which has been the subject of a great deal of research: the need for achievement (n-Ach), or a drive to reach attainable and challenging goals especially in the face of competition. McClelland and colleagues (1976) suggested that people tend to seek out situations that provide opportunities for satisfying this need. A child who aspires to become a professional basketball player might start training at a very young age, read books about the sport, and apply for basketball camp scholarships. A high school student dead-set on going to college may set up meetings with the college counselor, take practice SATs, and read books about how to write an exceptional application essay.

Need For Power

According to McClelland and colleagues (1976) some people are motivated by a need for power (n-Pow), or a drive to control and influence others. People with this need are motivated to project their importance through outward appearances. They may drive around in luxury cars, wear flashy designer clothing, and buy expensive houses. Some even flex their influence muscles on the pages of Facebook, building massive numbers of contacts just to show how important and popular they are. The need for power is one of many needs motivating people to use social media.

SOCIAL MEDIA and psychology

Some of the most enthusiastic users of Facebook—those who tend to have large numbers of contacts and wall posts—score high on assessments of a personality trait called narcissism (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). Narcissistic people are vain and self-absorbed; they seek prestige and power, and they may feel a sense of superiority over others. These characteristics shine through online, and presumably have a negative impact on the Facebook social climate (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Carpenter, 2012).

Some of the most enthusiastic users of Facebook—those who tend to have large numbers of contacts and wall posts—score high on assessments of a personality trait called narcissism (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008). Narcissistic people are vain and self-absorbed; they seek prestige and power, and they may feel a sense of superiority over others. These characteristics shine through online, and presumably have a negative impact on the Facebook social climate (Buffardi & Campbell, 2008; Carpenter, 2012).

Like all human beings, social media users are driven by the desire for love and belonging (the third level from the bottom on Maslow’s hierarchy). But social media may not be the answer for those who struggle to get those needs met in real life. One study of college students, for example, found no evidence that using Facebook cured lonely people of their loneliness. Those who were socially isolated offline were also socially isolated online (Freberg, Adams, McGaughey, & Freberg, 2010). In some cases, using social media actually intensified feelings of loneliness (DiSalvo, 2010). Perhaps this is because interactions with network “friends” tend to be more superficial than those in real life. Can anyone really maintain deep and meaningful relationships with 300 Facebook friends?

FACEBOOK A CURE FOR LONELINESS?

But there is a bright side. Facebook does appear to be a useful tool for strengthening established relationships (DiSalvo, 2010). A century ago, families were not as geographically scattered as they are today. Grandparents, siblings, and cousins might have lived in the same town or county, and this would have created more opportunities for love, affection, and belonging. These days, families are dispersed all over the globe, and staying connected through social media may be a lot easier (and cheaper) than buying airplane tickets. The bottom line is that social media can be used to satisfy a variety of needs, and the nature of these needs depends on both the user and the site.

We have now covered several important theories of motivation, including Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In the next section, we return our focus to the base of Maslow’s pyramid, where basic requirements such as hunger and thirst are represented. Sadly, many people in the world do not get those needs fulfilled.

show what you know

Question 9.4

1. Your instructor describes an interesting finding about gender differences regarding dating behavior. She explains that these behavior differences are ultimately motivated by evolutionary forces. She is using which of the following to support her explanation?

- operant conditioning

- arousal theory

- instinct theory

- homeostasis

c. instinct theory

Question 9.5

2. The ________ theory of motivation suggests biological needs and homeostasis motivate us to meet our needs.

- arousal

- instinct

- incentive

- drive-reduction

d. drive-reduction

Question 9.6

3. According to Maslow, the biological and psychological needs that motivate us to behave are arranged in a ________.

hierarchy of needs

Question 9.7

4. Self-determination theory proposes that we are motivated by three universal, fundamental needs: competence, relatedness, and autonomy. Describe one example for each of these needs.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following definitions. Competence means being able to reach goals through the mastery of everyday functioning (such as fixing meals, getting ready for work and school). Relatedness is the need to create relationships with others (for example, to make and keep friends, develop families). Autonomy means managing one’s behavior to reach personal goals (such as finishing one’s college degree).

Question 9.8

5. How does drive-reduction motivation differ from arousal motivation?

The drive-reduction theory of motivation suggests that biological needs and homeostasis motivate us to meet needs. If a need is not fulfilled, this creates a drive, or state of tension, that pushes us or motivates behaviors to meet the need. Once a need is met, the drive is reduced, at least temporarily, because this is an ongoing process, as the need inevitably returns. Arousal theory suggests that humans seek an optimal level of arousal, and what is optimal is based on individual differences. Behaviors can arise out of the simple desire for stimulation, or arousal, which is a level of alertness and engagement in the world, and people are motivated to seek out activities that fulfill this need. Drive-reduction theory suggests that the motivation is to reduce tension, but arousal theory suggests that in some cases the motivation is to increase tension.