9.4 Introduction to Emotion

SHARK ATTACK

For those longing for a quiet beach escape, Ocracoke Island on the North Carolina coast is hard to beat. A quaint island wrapped in 16 miles of pristine beach, Ocracoke is a perfect place for building sand-castles, collecting seashells, and riding the waves. The breeze is sweet, the water refreshing, and the sand soft on your feet. Circumstances are ideal for young children, except for the occasional rip current. Oh, and there’s one more thing: Beware of sharks.

One summer night in 2011, 6-year-old Lucy Mangum was splashing around on her boogie board at her family’s favorite Ocracoke beach. She was close to shore in water no deeper than 2 feet. Suddenly, Lucy let out a spine-chilling scream. Her mother Jordan, just feet away, spotted the fin of a shark cutting through the water. Running to swoop up her daughter, Jordan did not realize what had occurred—until she saw the blood streaming from her daughter’s right leg, which was “completely open” from heel to calf (Allegood, 2011, July 27). The shark had attacked Lucy.

Jordan did the right thing. She applied pressure to the gushing wound and called for help. Lucy’s father Craig, who happens to be an emergency room doctor, rushed over and looked at the wound. Right away, he knew it was severe and needed immediate medical attention (Stump, 2011, July 26). In the moments following the attack, Lucy was remarkably calm. “Am I going to die?” she asked her mom. “Absolutely not,” Jordan replied. “Am I going to walk?” Lucy asked. “Am I going to have a wheelchair?” It was too early to know (CBS News, 2011, July 26).

What Is Emotion?

Unprovoked shark attacks are extremely uncommon, occurring less than 100 times per year worldwide. And most attacks are not fatal. To put things in perspective, you are 75 times more likely to be killed by a bolt of lightning and 26 times more likely to be killed by a dog (Florida Museum of Natural History, 2011). Despite their rarity, shark attacks seem to be particularly fear provoking. Maybe the thought of becoming the prey of a wild creature reminds us that we are still, at some level, animals: vulnerable players in the game of natural selection.

Fear is an emotion you experience throughout your life. When you were a baby, you might have been afraid of the vacuum cleaner or the hair dryer. As you matured, your fears may have shifted to the dog next door or the monster in the closet. These days you might be scared of growing older, being diagnosed with a serious disease, or losing someone you love.

LO 10 Define emotions and explain how they are different from moods.

But what exactly is fear? That’s an easy question: Fear is an emotion. Now here’s the hard question: What is an emotion? An emotion is a psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience. In other words, emotion is an intensely personal experience; we cannot actually feel each other’s emotions firsthand. Emotion also has a physiological component; it is not only “in our heads.” For example, anger can make you feel hot, anxiety might cause sweaty palms, and sadness may sap your physical energy. Finally, emotion entails a behavioral expression. We scream and run when frightened, gag in disgust, and shed tears of sadness. Think about the last time you felt joyous. What was your inner experience of that joy, how did your body react, and what would someone have noticed about your behavior?

Thus, emotion is a subjective psychological state that includes both physiological and behavioral components. But are these three elements—psychology, physiology, and behavior—equally important, and in what order do they occur? The answer to these questions is still under debate, as is the very definition of emotion (Davidson, Scherer, & Goldsmith, 2002). With uncertainty about the cause and function of emotion, it comes as no surprise that many scholars are interested in studying it. Psychologists, physicians, neuroscientists, economists, biologists, geneticists, and others are working from a variety of perspectives to determine the nature of emotions (Coan, 2010), including the roles that the brain, body, and face play.

Moods Versus Emotions

Most psychologists agree that emotions are different from moods. Emotions are quite strong, but they don’t generally last as long as moods, and they are more likely to have an identifiable cause. An emotion is initiated by a stimulus, and it is more likely than a mood to motivate someone to action. Moods are longer-term emotional states that are less intense than emotions and do not appear to have distinct beginnings or ends (Kemeny & Shestyuk, 2008; Matlin, 2009; Oatley, Keltner, & Jenkins, 2006). An example might help clarify: Imagine your mood is happy, but a car cuts you off on the highway, creating a negative emotional response like anger.

Now let’s see how the three distinguishing characteristics of emotion (as opposed to moods) might apply to Lucy’s situation. When Lucy’s mother saw the wound from the shark bite, she remembers feeling “afraid” (CBS News, 2011, July 26). Her emotion (1) had a clear cause (the shark attacking her daughter) and (2) produced an immediate emotional reaction (fear), which (3) motivated her into action (applying pressure to the wound and calling for help).

Language and Emotion

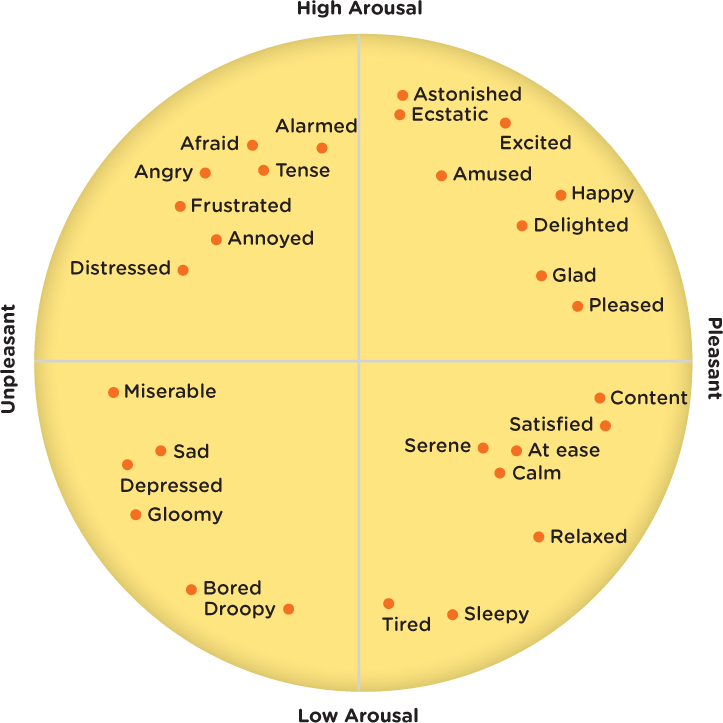

If you were Lucy’s mom, what words might you use to describe your fear—frightened, terrified, horrified, scared, petrified, spooked, aghast? Having a variety of labels at your disposal certainly helps when it comes to communicating your emotions. “I feel angry at you” conveys a slightly different meaning than “I feel resentful of you,” or “I feel annoyed by you.” The English language includes about 200 words to describe emotions. But does that mean we are capable of feeling only 200 emotions? Probably not. And if another language offers more descriptive words, speakers of that language don’t necessarily experience a broader array of emotions. Words and emotions are not one and the same, but they are closely linked. In fact, their relationship has captivated the interest of linguists from fields as different as anthropology, psychology, and evolutionary biology (Majid, 2012). Rather than focusing on words or labels, scholars typically characterize emotions along different dimensions. Izard (2007) suggests that we can describe emotions according to valence and arousal (Figure 9.3). The valence of an emotion refers to how pleasant or unpleasant it is. Happiness, joy, and pleasure are on the pleasant end of the valence dimension; anger and disgust lie on the unpleasant end. The arousal level of an emotion describes how active, excited, and involved a person is while experiencing the emotion, as opposed to how calm, uninvolved, or passive she may be. With valence and arousal level, we can compare and contrast emotions. The emotion of ecstasy, for example, has a high arousal level and a positive valence. Feeling relaxed has a low arousal and a positive valence. When Lucy looked down and saw the shark, she likely experienced an intense fear—high arousal, but low valence. Fortunately, for Lucy and her family, fear eventually gave way to more positive emotions. Let’s find out what happened.

show what you know

Question 9.12

1. ________ is a psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience, physiological component, and behavioral expression.

- A valence

- An instinct

- A mood

- An emotion

d. An emotion

Question 9.13

2. Emotions can be described along two dimensions: valence and ________.

arousal level

Question 9.14

3. On the way to a wedding, you get mud on your clothing. Describe how your emotion and mood would differ.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following definitions. Emotion is a psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience. It also has a physiological component and entails a behavioral expression. Emotions are quite strong, but they don’t generally last as long as moods. In addition, emotions are more likely to have an identifiable cause (that is, a reaction to a stimulus that provoked it), which has a greater probability of motivating a person to take some sort of action. Moods are longer-term emotional states that are less intense than emotions and do not appear to have distinct beginnings or ends. It is very likely that on your way to a wedding you are in a happy mood, and you have been that way for quite a while. If you were to get mud on your clothing, it is likely that you would experience an emotion such as anger, which might have been triggered by someone jumping in a large mud puddle and splashing you. Your anger would have a subjective experience (your feeling of anger), a physiological component (you felt your face flush with heat), and a behavioral expression (you glared angrily at the person who splashed you).