9.5 Theories of Emotion

FIGHT BACK

Within 35 minutes of the attack, Lucy was lifted off Ocracoke Island by helicopter and on her way to a trauma center in Greenville, North Carolina. The damage to her leg was extensive, with large tears to the muscle and tendons. She would need two surgeries, extensive physical therapy, and a wheelchair for some time after leaving the hospital (WRAL.com, 2011, July 26).

Within 35 minutes of the attack, Lucy was lifted off Ocracoke Island by helicopter and on her way to a trauma center in Greenville, North Carolina. The damage to her leg was extensive, with large tears to the muscle and tendons. She would need two surgeries, extensive physical therapy, and a wheelchair for some time after leaving the hospital (WRAL.com, 2011, July 26).

How did Lucy hold up during this period of extreme stress? According to lead surgeon Dr. Richard Zeri, the 6-year-old was “remarkably calm” (Allegood, 2011, July 27). But she did seem to harbor some negative feelings toward the shark, at least initially. “I hate sharks,” she told her parents (Stump, 2011, July 26). “I should have kicked him in the nose,” she reportedly said (Allegood, 2011, July 27). Eventually, Lucy forgave the shark: “I don’t care that the shark bit me,” she told reporters, “I forgive him” (Stump, 2011, July 26), but her initial reaction appeared to be defensive. Fighting back is not an unusual response; some victims have prevented sharks from attacking by grabbing their tails, punching them in the gills, and gouging their eyes (Cabanatuan & Sebastian, 2005, October 19; Caldicott, Mahajani, & Kuhn, 2001).

Emotion and Physiology

Such acts of self-defense are mediated by the sympathetic nervous system’s fight-or-flight response (Chapter 12). When faced with a stressful situation like a shark attack, stress hormones are released into the blood; breathing rate increases; the heart pumps faster and harder; blood pressure rises; the liver releases extra glucose into the bloodstream; and blood surges into the large muscles. All these physical changes prepare the body for confronting or fleeing the threat; hence the expression “fight or flight.” But fear is not the only emotion that involves dramatic physical changes. Tears pour from the eyes during intense sadness and joy. Anger is associated with sweating, an elevated heart rate, and increased blood flow to the hands, apparently preparing them to strike (Ekman, 2003).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we explained how the sympathetic nervous system prepares the body to respond to an emergency, whereas the parasympathetic nervous system brings the body back to a noncrisis mode through the “rest-and-digest” process. Here, we see how the autonomic nervous system is involved in physical experiences of emotion.

LO 11 Identify the major theories of emotion and describe how they differ.

Most psychologists agree that emotions and physiology are deeply intertwined. Some suggest there are basic emotions that are biologically determined; others promote a more cognitive approach, focusing on how thinking is involved in the experience of emotions. Furthermore, what they have not always agreed on is the precise order of events. What happens first: the body changes associated with emotion or the emotions themselves? That’s a no-brainer, you may be thinking. Emotions occur first, and then the body responds. American psychologist William James would not agree.

James–Lange Theory

In the late 1800s, James and Carl Lange, a Danish physiologist, working independently, derived similar explanations for emotion (James, 1890/1983; Lange & James, 1922). What is now known as the James–Lange theory of emotion suggests that a stimulus initiates a physiological reaction (for example, the heart pounding, muscles contracting, a change in breathing) and/or a behavioral reaction (such as crying or striking out), and this reaction leads to an emotion (Infographic 9.3). Emotions do not cause physiological or behavioral reactions to occur, as common sense might suggest. Instead, “we feel sorry because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble” (James, 1890/1983, p. 1066). In other words, changes in the body and behavior pave the way for emotions. Our bodies automatically react to stimuli, and awareness of this physiological reaction leads to the subjective experience of an emotion.

How might the James–Lange theory apply to our shark attack victim Lucy? It all begins with a stimulus, in this case the appearance of the shark and the pain of the bite. Next occur the physiological reactions (an increased heart rate, faster breathing, and so on) and the behavioral responses (screaming, trying to swim away). Finally, the emotion registers. Lucy feels fear. Imagine that Lucy, for some reason, had no physiological reaction to the shark—no rapid heartbeat, and so forth. Would she still experience the same degree of terror? According to the James–Lange theory, no. Lucy might see the shark and decide to flee, but she wouldn’t feel afraid.

The implication of the James–Lange theory is that each emotion has its own distinct physiological fingerprint. If this were the case, it would be possible to identify an emotion based on a person’s physiological/behavioral responses. Someone who is sad would display a different physiological/behavioral profile when feeling angry, for example. PET scans have confirmed that different emotions such as happiness, anger, and fear do indeed have distinct activation patterns in the brain, lending evidence in support of the James–Lange theory (Berthoz, Blair, Le Clec’h, & Martinot, 2002; Carlsson et al., 2004; Damasio et al., 2000; Salimpoor, Benovoy, Larcher, Dagher, & Zatorre, 2011).

However, critics of the James–Lange theory of emotion suggest it cannot fully explain emotional phenomena because (1) people who are incapable of feeling physiological reactions of internal organs (as a result of surgery or spinal cord injuries, for example) can still experience emotions; (2) the speed of an emotion is much faster than physiological changes occurring in internal organs; and (3) when physiological changes are made to the functions of internal organs (through a hormonal injection, for instance), emotions do not necessarily change (Bard, 1934; Cannon, 1927; Hilgard, 1987). In one experiment, researchers used surgery to stop animals from becoming physiologically aroused, yet the animals continued to exhibit behavior associated with emotion (such as growling and posturing; Cannon, 1927).

Cannon–Bard Theory

Walter Cannon (1927) and his student Philip Bard (1934) were among those who believed the James–Lange theory could not explain all emotions. The Cannon–Bard theory of emotion suggests that we do not feel emotion as a result of physiological and behavioral reactions, but rather these experiences occur simultaneously (Infographic 9.3). The starting point of this response is a stimulus in the environment.

Let’s use the Cannon–Bard theory to see how the appearance of a snake might lead to an emotional reaction. Imagine you are about to crawl into bed for the night. You pull back the sheets, and there, in YOUR BED, is a snake! According to the Cannon–Bard theory, the image of the snake will stimulate sensory neurons to relay signals in the direction of your cortex. But rather than rushing to the cortex, these signals pass through the thalamus, splitting in two directions—one toward the cortex and the other toward the hypothalamus.

When the neural information reaches the cortex and hypothalamus, several things could happen. First, the “thalamic–hypothalamic complex will be thrown into a state of readiness” (Krech & Crutchfield, 1958, p. 343), in a sense, waiting for the determination of whether the message will continue to the skeletal muscles and internal organs, instructing them to react. The neural information from the thalamus will arrive in the cortex at the same time, enabling you to “perceive” the snake on your bed. If it is just a rubber snake, this news will be sent from the cortex to the thalamic–hypothalamic complex, preventing the emergency signal from being sent to the skeletal muscles and internal organs. However, if the object in your bed is a real snake, then the emergency message will be forwarded to your skeletal muscles and internal organs, prompting a physiological and/or behavioral response (heart racing, jumping backward). At the same time, the thalamus sends a message to the cortex that this situation must be responded to right away. It is at this point, along with the perception of the snake, that an emotion is experienced. The emotion and physiological reaction occur simultaneously.

Critics of the Cannon–Bard theory suggest that the thalamus might not be capable of carrying out this complex processing on its own and that other areas may contribute (Beebe-Center, 1951; Hunt, 1939). Research suggests that the limbic system, hypothalamus, and prefrontal cortex are also substantially involved in processing emotions (Kolb & Whishaw, 2009; Northoff et al., 2009).

Cognition and Emotion

Schachter–Singer Theory

Schachter and Singer (1962) also took issue with the James–Lange theory, primarily because different emotions do not have distinct and recognizable physiological responses. They suggested there is a general pattern of physiological arousal caused by the sympathetic nervous system, and this pattern is common to a variety of emotions. The Schachter–Singer theory of emotion proposes that the experience of emotion is the result of two factors: (1) physiological arousal, and (2) a cognitive label for this physiological state (the arousal). According to this theory, if someone experiences physiological arousal, but doesn’t know why it has occurred, she will label the arousal and explain her feelings based on her “knowledge” of the environment (that is, in recognition of the context of the situation). Depending on the “cognitive aspects of the situation,” the physiological arousal might be labeled as joy, fear, anxiety, fury, or jealousy (Infographic 9.3).

When you are certain about what is causing your physiological arousal, you won’t look to the situation to label the emotion. Imagine you are about to deliver an important speech in front of hundreds of people and your heart is pounding. If you are afraid of public speaking, then you know what is causing your heart to pound and you would label the arousal as fear. But sometimes ambiguity exists in a situation, and you might not be sure how to label an emotion. For example, if your heart is pounding and you are not afraid of public speaking, you might try to label the arousal based on your assessment of the situation (I drank a lot of coffee, I am excited to give the speech, or Someone special is in the crowd). However, it is unlikely you will report feeling any emotion without experiencing physiological arousal (Schachter & Singer, 1962).

To test their theory, Schachter and Singer injected participants (male college students) with either epinephrine to mimic physiological reactions of the sympathetic nervous system (such as increased blood pressure, respiration, and heart rate) or a placebo. The researchers also divided the participants into the following groups: those who were informed correctly about possible side effects (for example, tremors, palpitations, flushing, or accelerated breathing), those who were misinformed about side effects, and others who were told nothing about side effects.

The participants were left in a room with a “stooge,” a confederate secretly working for the researcher, who was either euphoric (elated) or angry. When the confederate behaved euphorically, the participants who had been given no explanation for their physiological arousal were more likely to report feeling happy or appeared happier. When the confederate behaved angrily, participants given no explanation for their arousal were more likely to appear or report feeling angry. Through observation and self-report, it was clear the participants who did not receive an explanation for their physiological arousal could be manipulated to feel either euphoria or anger, depending on the confederate they were paired with. The participants who were accurately informed about side effects did not show signs or report feelings of euphoria or anger. Instead, they accurately attributed their physiological arousal to the side effects clearly explained to them at the beginning of the study (Schachter & Singer, 1962).

Some have criticized the Schachter–Singer theory, though, suggesting it overstates the link between physiological arousal and the experience of emotion (Reisenzein, 1983). Studies have shown that people can experience an emotion without labeling it, especially if neural activity sidesteps the cortex, heading straight to the limbic system (Dimberg, Thumberg, & Elmehed, 2000; Lazarus, 1991a). We will discuss this process in the section below on fear.

Cognitive Appraisal and Emotion

Rejecting the notion that emotions result from cognitive labels of physiological arousal, Lazarus (1984, 1991a) suggested that emotion is the result of the way people appraise or interpret interactions they have in their surroundings. We appraise what is happening in our environment based on its significance. It doesn’t matter if someone can label an emotion or not; he will experience the emotion nonetheless. We’ve all felt emotions such as happiness, anxiety, shame, and so forth, and we don’t need an agreed upon label or word to experience them. Babies, for example, can feel emotions long before they are able to label them with words.

Lazarus also suggested that emotions are adaptive, because they help us cope with the surrounding world. In a continuous feedback loop, as an individual’s appraisal or interpretation of his environment changes, so do his emotions (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Lazarus, 1991b). Emotion is a very personal reaction to the environment. This notion became the foundation of the cognitive appraisal approach to emotion (Infographic 9.3). The cognitive-appraisal approach suggests that the appraisal causes an emotional reaction, whereas the Schachter–Singer theory asserts the arousal comes first and then has to be labeled.

Responding to the cognitive-appraisal approach, Zajonc (zay-ənts) (1984) suggested that thinking does not always have to be involved when we experience an emotion. As Zajonc (1980) saw it, emotions can precede thoughts and may even cause them. He also suggested we can experience emotions without interpreting what is occurring in the environment. Emotion can influence cognition and cognition can influence emotion.

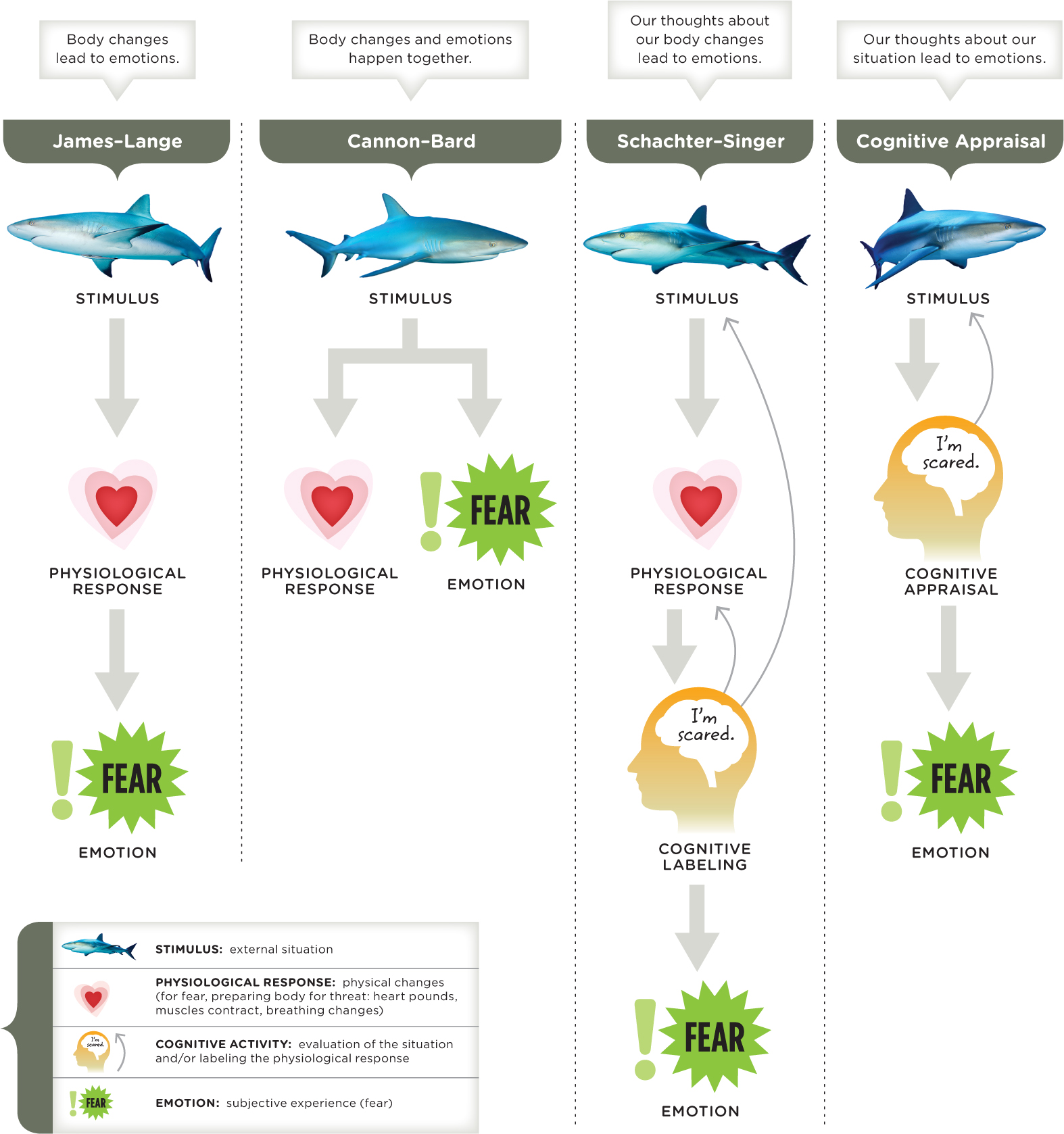

INFOGRAPHIC 9.3: Theories of Emotion

Imagine you are swimming and you think you see a shark. Fear pierces your gut, sending your heart racing as you swim frantically to shore. Or is it actually your churning stomach and racing heart that cause you to feel so terrified? And what part, if any, do your thoughts play in this process? Psychologists have long debated the order in which events lead to emotion. Let’s compare four major theories, each proposing a different sequence of events.

One of the main areas of disagreements among the theories just described concerns cognition and how it fits into the picture. Forgas (2008) proposed that the association between emotion and cognitive activity is complex as well as bidirectional: “Cognitive processes determine emotional reactions, and, in turn, affective states influence how people remember, perceive, and interpret social situations and execute interpersonal behaviors”.

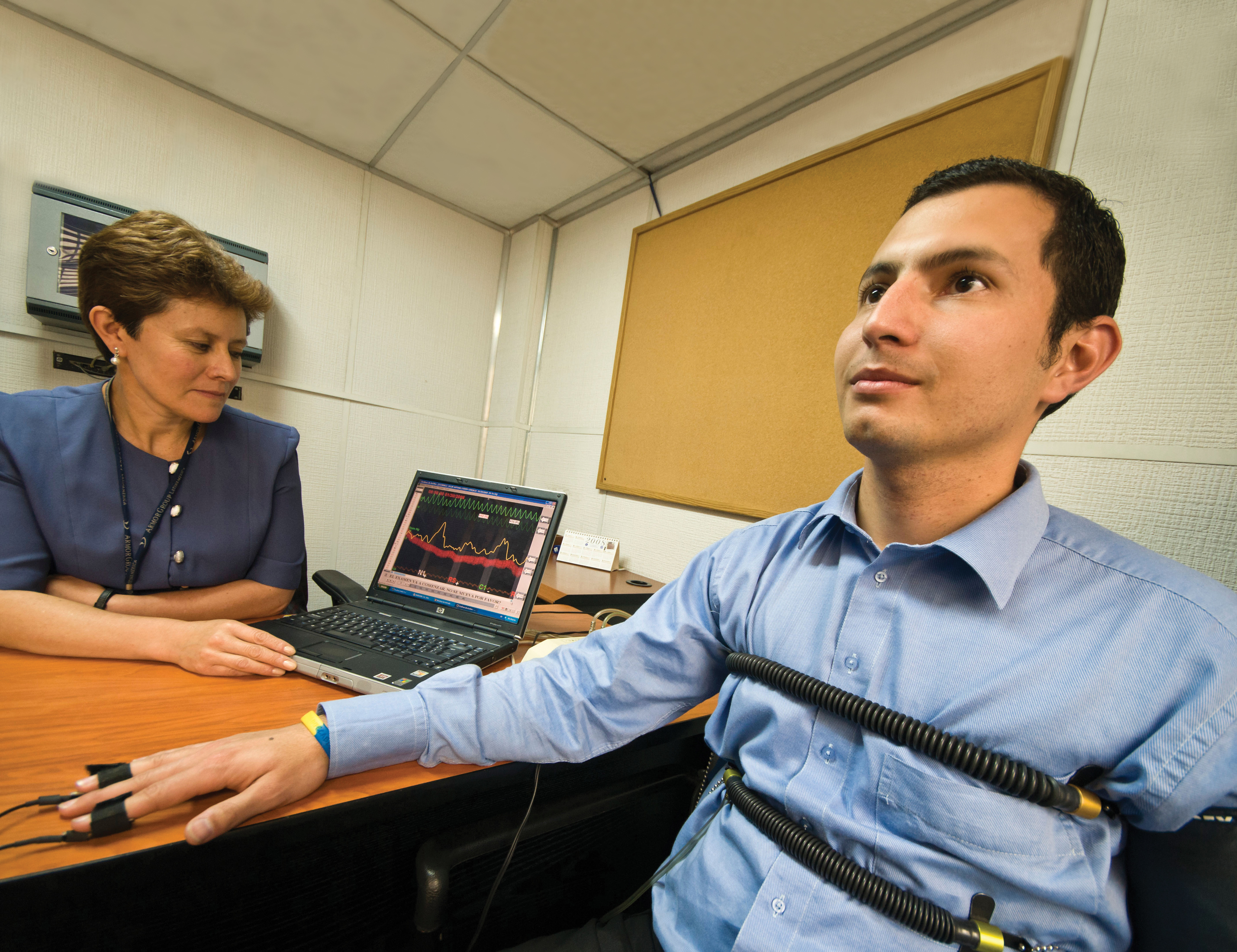

Emotions are complex and closely related to cognition, physiology, and perception. We know, for example, that certain physiological changes are likely to occur when a person is frightened, anxious, or attempting to conceal deceit. In fact, some important technologies are built on this very premise. Perhaps you’ve heard of the polygraph?

CONTROVERSIES

Problems with Polygraphs

Since its introduction in the early 1900s, the polygraph, or “lie detector” test, has been used by government agencies for a variety of purposes, including job screening, crime investigation, and spy identification (Department of Justice, 2006; Nature, 2004, April 15). The FBI (along with many police departments) will not even hire applicants unless they undergo a thorough background check, which includes a polygraph (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2013). Despite the widespread use of this technology, many scientists have serious doubts about its validity (Nature, 2004, April 15).

Since its introduction in the early 1900s, the polygraph, or “lie detector” test, has been used by government agencies for a variety of purposes, including job screening, crime investigation, and spy identification (Department of Justice, 2006; Nature, 2004, April 15). The FBI (along with many police departments) will not even hire applicants unless they undergo a thorough background check, which includes a polygraph (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2013). Despite the widespread use of this technology, many scientists have serious doubts about its validity (Nature, 2004, April 15).

What is this so-called lie detector and how does it work? The polygraph is a machine that attempts to determine if someone is lying by measuring physiological arousal presumed to be associated with deceit. When some people lie, they feel anxious, which causes changes in blood pressure, heart rate, breathing, and production of sweat. By monitoring these variables, the polygraph can theoretically detect when a person feels stressed from lying (American Psychological Association [APA], 2004).

But here’s the problem: Biological signs of anxiety do not always go hand-in-hand with deception. There are many other reasons one might feel nervous while taking a polygraph test. Just sitting in a room with an interrogator and being attached to recording equipment may be enough to get the heart racing. And certain people are capable of lying without feeling stressed, and thus their deceit might slip past the polygraph undetected. A person with antisocial personality disorder (discussed in Chapter 13), for example, may not experience the typical physiological changes associated with lying (Simpson, 2008).

JUST HOW ACCURATE ARE POLYGRAPH TESTS?

As you probably guessed, results from the polygraph are not very accurate. Research suggests that error rates are anywhere from 25 to 75% (Saxe, 1994). Searching for a better alternative, some have turned to fMRI technology (Hakun et al., 2009; Simpson, 2008), but its results are not completely reliable either. According to one group of researchers, the ability of fMRI to detect lying was “better than chance but far from perfect” (Monteleone et al., 2009, p. 537).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described how fMRI technology reveals patterns of blood flow in areas of the brain, which is a good indicator of how much oxygen is being used as a result of activity there. Here, we see how researchers are trying to use this technology to detect lying.

Thus, it appears that lie detection technologies are not much better than old-fashioned observation. If we rely on body language, facial expressions, and other social cues, our lie-detection accuracy is no more than 60% (Gamer, 2009). We may not be skilled at spotting dishonesty, but we are pros at identifying basic emotions like happiness, anger, and fear. Just imagine Lucy and her parents during a television interview 1 week after the shark attack. What emotions would be written on their faces?

FACE VALUE

Lucy was lucky. With a 90% tear to the muscle and tendon and a severed artery, she could have easily lost her leg. But the surgeries went well. Just a week after the horrific incident, she was flashing a bashful grin on national television. Seated between mom and dad, Lucy played with her mother’s fingers, squirmed, and then nestled her head under her father’s arm. She looked as bright-eyed and vibrant as any child her age (MSNBC.com, 2011, July 26).

Lucy was lucky. With a 90% tear to the muscle and tendon and a severed artery, she could have easily lost her leg. But the surgeries went well. Just a week after the horrific incident, she was flashing a bashful grin on national television. Seated between mom and dad, Lucy played with her mother’s fingers, squirmed, and then nestled her head under her father’s arm. She looked as bright-eyed and vibrant as any child her age (MSNBC.com, 2011, July 26).

“The prognosis is great,” Lucy’s father Craig told TODAY’s Ann Curry. “It’s going to take some time and some physical therapy, but she’s going to be, you know, back and running and playing like she should” (MSNBC.com, 2011, July 26). The look on Craig’s face was calm, happy. Jordan also appeared relieved. Their little girl was going to be okay.

Suppose you knew nothing about Lucy’s shark attack, and someone showed you an image of Lucy’s parents during that television interview. Would you be able to detect the relief in their facial expressions? How about someone from Japan, Trinidad, or New Zealand: Would a cultural outsider also be able to “read” the emotions written across Craig and Jordan’s faces? If we could go back in time and pose this question to Charles Darwin, we suspect his answer would be yes. As Darwin saw it, humans use a similar set of facial expressions to display their emotions and have a natural ability for recognizing those emotions in others.

LO 12 Discuss evidence to support the idea that emotions are universal.

Writing in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872/2002), Darwin suggested that interpreting facial expressions is not something we learn but rather is an innate ability that evolved because it promotes survival. Sharing the same facial expressions allows for communication. Being able to identify the emotions of others—like the fear in a friend who has just spotted a snake on the trail—would seem to come in handy. Thus, if facial expressions are truly unlearned and universal, then people from all different cultures ought to interpret them in the same way. A “happy face” should look much the same wherever you go, from the United States to the Pacific island of New Guinea.

Ekman’S Faces

Some four decades ago, psychologist Paul Ekman traveled to a remote mountain region of New Guinea to study an isolated group of indigenous peoples. Ekman and his colleagues were very careful in selecting their participants, choosing only those who were unfamiliar with Western facial behaviors—people who were unlikely to know the signature facial expressions we equate with basic emotions like disgust and sadness. The participants didn’t speak English, nor had they watched Western movies, worked for anyone with a Caucasian background, or lived among Westerners. The study went something like this: The researchers told the participants stories conveying various emotions such as fear, happiness, and anger. In the story conveying fear, for example, a man is sitting alone in his house with no knife, axe, bow, or any weapon to defend himself. Suddenly, a wild pig appears in his doorway, and he becomes frightened that the pig will bite him. Next, the researchers asked the participants to match the emotion described in the story to a picture of a person’s face (choosing from among 6–12 sets of photographs). The results indicated that the same facial expressions represent the same basic emotions across cultures (Ekman & Friesen, 1971). And so it seems, a “happy face” really does look the same to people in the United States and New Guinea.

Further evidence for the universal nature of these facial expressions is apparent in children born blind; although they have never seen a human face demonstrating an emotion, their smiles and frowns are similar to those of sighted children (Galati, Scherer, & Ricci-Bitti, 1997; Matsumoto & Willingham, 2009).

LO 13 Indicate how display rules influence the expression of emotion.

across the WORLD

Can You Feel the Culture?

Although the expression of some basic emotions appears to be universal, culture acts like a filter, determining the appropriate contexts in which to exhibit them. According to Mohamed (the Somali American we introduced earlier in the chapter), people from Somalia tend to be much less expressive than those born in the United States. “I have cousins who have just come to America, and even [now] when they have been here for about five years, they still like to keep to themselves about personal feelings,” says Mohamed. This is especially true when it comes to interacting with people outside the immediate family.

Although the expression of some basic emotions appears to be universal, culture acts like a filter, determining the appropriate contexts in which to exhibit them. According to Mohamed (the Somali American we introduced earlier in the chapter), people from Somalia tend to be much less expressive than those born in the United States. “I have cousins who have just come to America, and even [now] when they have been here for about five years, they still like to keep to themselves about personal feelings,” says Mohamed. This is especially true when it comes to interacting with people outside the immediate family.

These differences Mohamed observes are probably reflections of display rules. A culture’s display rules provide the framework or guidelines for when, how, and where an emotion is expressed. Think about some of the display rules in American culture. Negative emotions such as anger are often hidden in social situations. Suppose you are furious at a friend for forgetting to return a textbook she borrowed last night. You probably won’t reveal your anger as you sit among other students. Other times display rules compel you to express an emotion you are not feeling. Your friend gives you a birthday gift that really isn’t you. Do you say, “This is not my style. I think I’ll exchange it for a store credit,” or “Thank you so much” and smile graciously?

WHEN TO REVEAL, WHEN TO CONCEAL

Generally speaking, Americans tend to be fairly expressive. Showing emotion, particularly positive emotions, is socially acceptable. This is less the case in Japan, where people rarely reveal their feelings in public. One group of researchers secretly videotaped Japanese and American students while they were watching film clips that included surgeries, amputations, and other events commonly viewed as repulsive. Japanese and American participants showed no differences in their responses to the clips when they didn’t think researchers were watching. The great majority demonstrated similar facial expressions of disgust and emotional reactions in response to the stress-inducing clips. But when a researcher was present, the Japanese were more likely than the Americans to conceal their negative expressions with smiles (Ekman et al., 1987). This tendency to hide feelings from the researcher is the result of cultural display rules.

Facial Feedback Hypothesis

While we are on the topic of facial expressions, let’s take a brief detour back to the very beginning of the chapter when Mohamed arrived in his first-grade classroom speaking no English. Without a common language to communicate, Mohamed turned to a more universal form of communication: smiling. It is probably safe to assume that most of Mohamed’s classmates took this to mean he was enjoying himself, as smiling is viewed as a sign of happiness in virtually every corner of the world. It also seems plausible that Mohamed’s smiling had a positive effect on his classmates, making them more likely to approach and befriend him. But how do you think the act of smiling affected Mohamed?

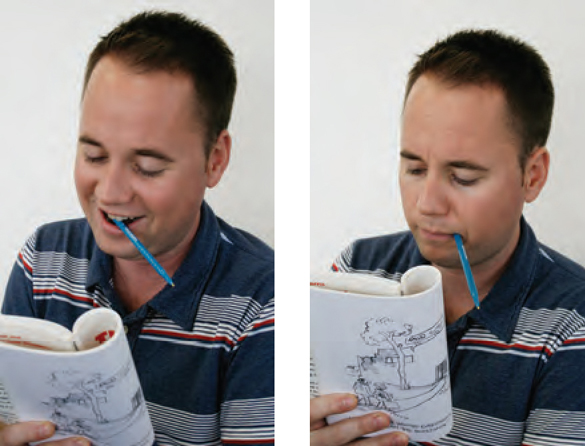

Believe it or not, the simple act of smiling can make a person feel happier. Although facial expressions are caused by the emotions themselves, they sometimes affect the experience of that emotion. This is known as the facial feedback hypothesis (Buck, 1980), and if it is correct, we should be able to manipulate our emotions through our facial activities. Try this for yourself.

try this

Take a pen and put it between your teeth, with your mouth open for about half a minute. Now, consider how you are feeling. Next, hold the pen with your lips, making sure not to let it touch your teeth, for half a minute. Again, consider how you are feeling.

If you are like the participants in a study conducted by Strack, Martin, and Stepper (1988), holding the pen in your teeth should result in your seeing the objects and events in your environment as funnier than if you hold the pen with your lips. Why would that be? Take a look at the photo to the right and note how the person holding the pen in his teeth seems to be smiling—the feedback of those smiling muscles leads to a happier mood.

We are now nearing the end of this chapter—and what an emotional one it has been! Before wrapping things up, let’s examine various kinds of emotions humans can experience, narrowing our gaze on fear and happiness.

show what you know

Question 9.15

1. The ________ theory of emotion suggests that changes in the body and behavior lead to the experience of emotion.

James–Lange

Question 9.16

2. ________ of a culture provide a framework for when, how, and where an emotion is expressed.

- Beliefs

- Display rules

- Feedback loops

- Appraisals

b. Display rules

Question 9.17

3. The ________ suggests the expression of an emotion can affect the experience of that emotion.

- James–Lange theory

- Cannon–Bard theory

- Schachter–Singer theory

- facial feedback hypothesis

d. facial feedback hypothesis

Question 9.18

4. Name two ways in which the Cannon–Bard and Schachter–Singer theories of emotion are different.

Answers may vary. See Infographic 9.3. The Cannon–Bard theory of emotion suggests that environmental stimuli are the starting point for emotions, and that body changes and emotions happen together. The Schachter–Singer theory of emotion suggests there is a general pattern of physiological arousal caused by the sympathetic nervous system, and this pattern is common to a variety of emotions. Unlike the Cannon–Bard theory, the Schachter–Singer theory suggests our thoughts about our body changes lead to emotions. The experience of emotion is the result of two factors: physiological arousal and a cognitive label for this physiological state (the arousal). Cannon–Bard did not suggest that a cognitive label is necessary for emotions to be experienced.

Question 9.19

5. What evidence exists that emotions are universal?

Darwin suggested that interpreting facial expressions is not something we learn but rather is an innate ability that evolved because it promotes survival. Sharing the same facial expressions allows for communication. Research on an isolated group of indigenous peoples in New Guinea suggests that the same facial expressions represent the same basic emotions across cultures. In addition, the fact that children born deaf and blind have the same types of expressions of emotion as children who are not deaf or blind suggests the universal nature of these displays, and thus the emotions that trigger them.