10.3 The Birds and the Bees

THE MAKING OF A SEXPERT

Dr. Stephanie Buehler grew up in California’s San Fernando Valley during the 1970s, when the sexual revolution was in full gear. During this time in American history, many people questioned conventional notions about sex and explored different avenues of sexual expression. “There was a lot of sexual activity at that time,” explains Dr. Buehler, who had many gay, bisexual, and transgender friends. “I was really exposed to a lot of different aspects of sexuality.” At home, she knew it was okay to ask her parents questions about sex and birth control. So, it was no big deal when Stephanie’s family went with her to see the avant-garde and sexually explicit movie Last Tango in Paris (which received an X rating at the time of its release, and currently has an NC-17 rating).

Dr. Stephanie Buehler grew up in California’s San Fernando Valley during the 1970s, when the sexual revolution was in full gear. During this time in American history, many people questioned conventional notions about sex and explored different avenues of sexual expression. “There was a lot of sexual activity at that time,” explains Dr. Buehler, who had many gay, bisexual, and transgender friends. “I was really exposed to a lot of different aspects of sexuality.” At home, she knew it was okay to ask her parents questions about sex and birth control. So, it was no big deal when Stephanie’s family went with her to see the avant-garde and sexually explicit movie Last Tango in Paris (which received an X rating at the time of its release, and currently has an NC-17 rating).

With this upbringing, Dr. Buehler was fairly relaxed talking about sex, and therefore her pursuit of a career as a sex therapist would seem like a plausible path. But graduate school looked like a long shot for a girl growing up in the 1970s, when women were just beginning to establish themselves as a major presence in the workforce. After graduating from college, the first person in her immediate family to do so, she became a teacher at an inner-city elementary school, and then decided to pursue a master’s degree and eventually a doctorate in psychology. Her PsyD concentration was family therapy, but another interest was brewing beneath the surface. During couples’ role-playing sessions in class, Dr. Buehler always was the student asking questions about sex: “What about your sex life?” “What’s going on in the bedroom?” She recalls her classmates looking at her and asking, “Why are you bringing that up? What does that have to do with anything?” The answer, she can now state with confidence, is a whole lot.

Dr. Buehler: Which gender visits your office more frequently?

After working as a licensed psychotherapist for several years, Dr. Buehler began her sex therapy training. She found it so rewarding that she launched her own sex therapy institute, The Buehler Institute in Newport Beach, California. “I just find I’m never, ever bored with my work,” says Dr. Buehler. Sexuality is quite personal…and that means that everybody is quite different.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex

When you think of sex, what comes to mind? Genitals? Intercourse? To grasp the complexity of sexual experiences, we must understand the basic physiology of the sexual response. Enter William Masters and Virginia Johnson and their pioneering laboratory research, which included the study of approximately 10,000 distinct sexual responses of 312 male and 382 female participants (Masters & Johnson, 1966).

LO 6 Describe the human sexual response as identified by Masters and Johnson.

Human Sexual Response Cycle

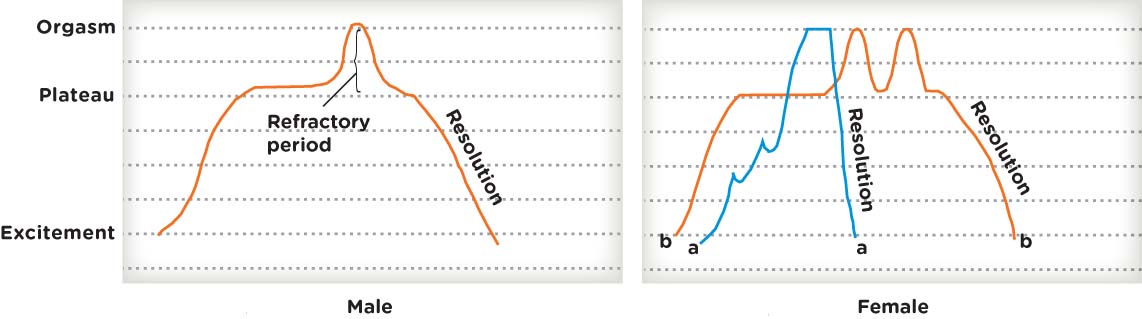

Masters and Johnson made some of the most important contributions to the study of the human sexual response. Their research started in 1954, not exactly a time when sex was thought to be an acceptable subject for dinner conversation. Nevertheless, almost 700 people volunteered to participate in their study, which lasted a little more than a decade (Masters & Johnson, 1966). In particular, Masters and Johnson were interested in determining the physiological responses that occurred during sexual activity, such as masturbation and intercourse. They used a variety of instruments to measure blood flow, body temperature, muscular changes, and heart rate. What they discovered is that most people experience a similar physiological sexual response, which can result from oral stimulation, manual stimulation, vaginal intercourse, or masturbation. Men and women tend to follow a similar pattern or cycle: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution (Figure 10.2). It is important to note, though, that these phases vary for each individual in terms of duration.

Sexual arousal begins during the excitement phase. This is when physical changes start to become evident. Muscles tense, the heartbeat quickens, breathing accelerates, the nipples become firm, and blood pressure rises a bit. In men, the penis becomes erect, the scrotum constricts, and the testes pull up toward the body. In women, the vagina lubricates and the clitoris swells (Levin, 2008).

Many factors can dampen the sexual excitement of this phase, among them unhappy babies and ringing phones. But would you guess that a woman’s tears can ruin the moment?

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Crying Women Turn Men Off

Weeping releases a chemical that reduces sexual arousal.

Women may have a more subtle way of telling men “no” than anyone imagined. Chemical cues in their tears signal that they are not interested in romantic activities, according to a study published online January 6 in Science.

Crying reveals a person’s mood, but its evolutionary origins have long been a mystery. Because emotional tears have a different chemical makeup than those evoked by irritants in the eye, cognitive neuroscientist Noam Sobel of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, wondered whether emotional tears relay chemical messages to others.

Sobel and his research team collected tears from self-professed “easy criers” as they watched sad movies. Later, the researchers held jars containing the odorless tears and pads that had been dipped in the tears under men’s noses.

These men rated female faces as less sexually attractive than did men who sniffed saline. Moreover, their sexual excitement dropped, as indicated by their own reports and by levels of testosterone in their saliva.

The researchers then scanned the men’s brains as they watched a titillating movie scene using functional MRI. Brain regions associated with sexual arousal showed less activity in men who sniffed tears compared with those who sniffed saline.

The findings represent the first evidence that human tears send chemical messages, Sobel reports. Because a decrease in testosterone levels is linked to reduced hostility, he speculates that weeping dampens not only the libido but also violent behavior. “If the signal really lowers aggression toward you, then the evolutionary value of crying is clear,” he says. Janelle Weaver. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2011 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Assuming no tears are shed during the excitement phase, the next likely step is the plateau phase. There are no clear physiological signs to mark the beginning of this phase, but it is the natural progression from the excitement phase. During the plateau phase, the muscles continue to tense, breathing and heart rate increase, and the genitals begin to change color as blood fills this area. This phase is usually quite short-lived, lasting only a few seconds to minutes.

The shortest phase of the sexual response cycle is the orgasm phase. As the peak of sexual response is reached, an orgasm occurs, which is a powerful combination of extremely gratifying sensations and a series of rhythmic muscular contractions. When men and women are asked to describe their orgasmic experiences, it is very difficult to differentiate between them. Brain activity observed via PET scans is also very similar (Georgiadis, Reinders, Paans, Renken, & Kortekaas, 2009; Mah & Binik, 2001).

The final phase of the sexual response cycle, according to Masters and Johnson, is called the resolution phase. This is when bodies return to a relaxed state. Without further sexual arousal, the body will immediately begin the resolution phase. The blood flows out of the genitals, and blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing slow to normal. Men lose their erection, the testes move down, and the skin of the scrotum loosens. Men will also experience a refractory period, an interval during which they cannot attain another orgasm. This can last from minutes to hours, and typically the older the man is, the longer the refractory period lasts. For women, the resolution phase is characterized by a decrease in clitoral swelling and a return to the normal labia color. Women do not experience a refractory period, and if sexual stimulation continues, some are capable of having multiple orgasms.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we noted that Maslow in particular emphasized our deep-seated need to feel loved, to experience affection, and to belong to a group. These needs motivate us to seek out relationships, which can include sexual activities.

Masters and Johnson’s landmark research has led to further studies of the physiological aspects of the sexual response cycle, and although their basic model is viewed as valid, research suggests there may be the need for “correction or modification, or additional explanation” (Levin, 2008, p. 2). As mentioned, sex is different for every person, and not everyone fits neatly into the same model.

Armed with this knowledge about the physiology of sex, let’s move on to its underlying psychology. How are sexual activities shaped by learning, relationships, and the need to be loved and belong?

Sexual Orientation

LO 7 Define sexual orientation and summarize how it develops.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA, 2008), sexual orientation is the “enduring pattern” of sexual, romantic, and emotional attraction that individuals exhibit toward the same sex, opposite sex, or both sexes. When attracted to members of the opposite sex, sexual orientation is heterosexual. When attracted to members of the same sex, sexual orientation is homosexual. When attracted to members of the same sex and members of the opposite sex, sexual orientation is bisexual, although most people tend to prefer one sex or the other. Those who do not feel sexually attracted to others are referred to as asexual. Lack of interest in sex does not necessarily prevent a person from maintaining relationships with spouses, partners, or friends, but little is known about the impact of asexuality because research on the topic is scarce. We can’t be sure how many people would consider themselves asexual, but by one estimate, they constitute 1% of the population (Crooks & Baur, 2014). Dr. Buehler’s mentor once explained sexual orientation like this: There is a universe of orientations and identities, and each person gets to put him- or herself in the constellation.

There is also a universe of labels for different sexual orientations. In America, the most common terminology refers to a homosexual woman as a “lesbian,” and a homosexual man as “gay” (APA, 2008). But sexual orientation is not a trait or characteristic one possesses. It is a label that reflects the relationships someone establishes and the qualities of those relationships, including degree of intimacy, mutual goals, commitment, and affection. We essentially become members of the group with which we have the most in common and in which we are the most comfortable, thus allowing us to build satisfying romantic relationships.

What’s in a Number?

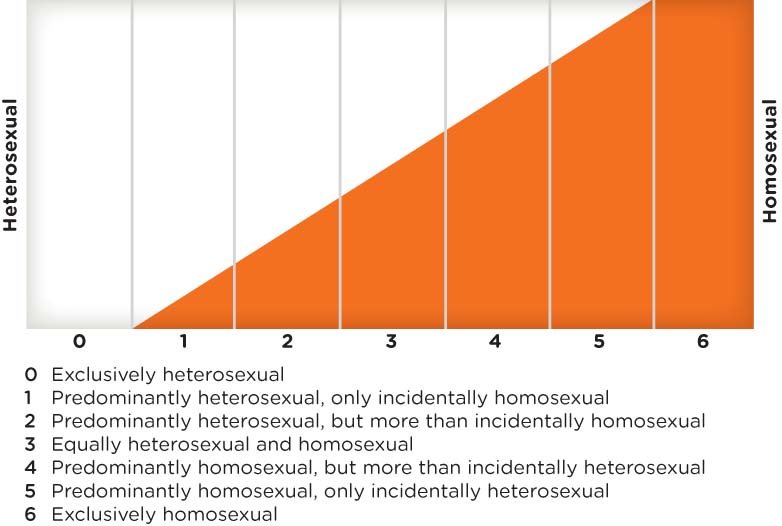

What percentage of the population is heterosexual? How about homosexual and bisexual? These questions may seem straightforward, but they are not easy to answer. This is partly because there are no clear-cut criteria for identifying individuals as homosexual, heterosexual, or bisexual. In other words, there is a vast spectrum representing sexual orientation. At one end are people who are “exclusively heterosexual” and at the other end are those considered “exclusively homosexual.” Between these two poles is considerable variation (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Figure 10.3). Some people might be exploring their sexuality, but not necessarily exhibiting a particular orientation, and this adds to the variability of rates. Estimates are available, but definitions of sexual orientation vary across cultures, and findings can be inconsistent as a result of differing survey designs: data collection in different years, the use of different age groups, different wording of questions, and so forth (Mosher, Chandra, & Jones, 2005). According to one estimate, 8 million people in the United States, or 3.5% of the adult population, are homosexual or bisexual (Gates, 2011).

Other estimates suggest the homosexual population is as low as 1% (referring only to same-sex behavior) and as high as 24% (defined as any sexual attraction to the same sex). This high end refers specifically to young women, who show greater fluidity in their sexual attractions and orientations (Ainsworth & Baumeister, 2012; Savin-Williams, 2009). As you digest these statistics, remember that sex is, first and foremost, a human experience. We may have different preferences, but our bodies react to sexual activity in similar ways. As Masters and Johnson (1979) demonstrated, we all experience a similar sexual response cycle, regardless of orientation. Even our brains display similar patterns of activity, apparent from fMRI and PET studies, when we feel sexual desire (Diamond & Dickenson, 2012). What makes us different is what we find sexually arousing (Cerny & Janssen, 2011).

How Sexual Orientation Develops

We are not sure how sexual orientation develops, although most research supports biological factors (a topic we will revisit in a little while). Among professionals in the field, there is near agreement that human sexual orientation is not a matter of choice. Research has focused on everything from genetics to culture, but there is no strong evidence that sexual orientation is determined by one particular factor (or set of factors). Instead, it appears to result from an interaction between nature and nurture, but this is still under investigation, and may never be fully determined or understood (APA, 2008).

Genetics and Sexual Orientation

To determine the influence of biology in sexual orientation, we turn to twin studies, which are commonly used to examine the degree to which nature and nurture contribute to psychological traits. Since monozygotic twins share 100% of their genetic make-up, we expect them to share more genetically influenced characteristics than dizygotic twins, who only share about 50% of their genes. In a large study of Swedish twins, researchers explored the impact of genes and environment on “same-sex sexual behavior” (2,320 monozygotic twin pairs, 1,506 dizygotic twin pairs). In their sample, the monozygotic twins were moderately more likely than the dizygotic twins to have the same sexual orientation. They also found that same-sex sexual behavior for monozygotic twins had heritability estimates around 34–39% for men, and 18–19% for women (Långström, Rahman, Carlström, & Lichtenstein, 2010). These findings highlight two important factors: Men and women differ in terms of the heritability of same-sex sexual behavior, and the influence of the environment is substantial.

Researchers have searched for specific genes that might influence sexual orientation. Some have suggested that genes associated with male homosexuality might be transmitted by the mother. In one key study, around 64% of male siblings who were both homosexual had a set of several hundred genes in common, and these genes were located on the X chromosome (Hamer, Hu, Magnuson, Hu, & Pattatucci, 1993). But critics suggest this research was flawed, and no replications of this “gay gene” have been published since the original study (O’Riordan, 2012).

The Brain and Sexual Orientation

Researchers have also studied the brains of people with different sexual orientations, and their findings are interesting. LeVay (1991) discovered that a “small group of neurons” in the hypothalamus of homosexual men was almost twice as big as that found in heterosexual men. He did not suggest this size difference was indicative of homosexuality, but he did find it intriguing. LeVay also noted that these differences could have been the result of factors unrelated to sexual orientation. More recently, researchers using MRI technology found the corpus callosum to be thicker in homosexual men (Witelson et al., 2008). With the help of MRI and PET, some researchers are studying the neurobiological foundations of sexual orientation, trying to determine if there are similarities in functioning and connectivity between those attracted to women (homosexual women and heterosexual men), as well as between those attracted to men (homosexual men and heterosexual women) (Savic & Lindström, 2008).

Hormones, Antibodies, and Sexual Orientation

How do differences arise in the brain? They may emerge before birth. As we noted earlier, hormones (estrogen and androgens) secreted by the fetal gonads play a role in the development of reproductive anatomy. One hypothesis is that the presence of androgens (the hormones secreted primarily by the male gonads) influences the development of a sexual orientation toward women. This would lead to heterosexual orientation in men, but homosexual orientation in women (Mustanski, Chivers, & Bailey, 2002). Because it would be unethical to manipulate hormone levels in pregnant women, researchers rely on cases in which hormones are elevated because of a genetic abnormality or medication taken by a mother. For example, high levels of androgens early in a pregnancy may cause girls to be more “male-typed,” and promote the development of a homosexual orientation (Berenbaum, Blakemore, & Beltz, 2011; Jordan-Young, 2012).

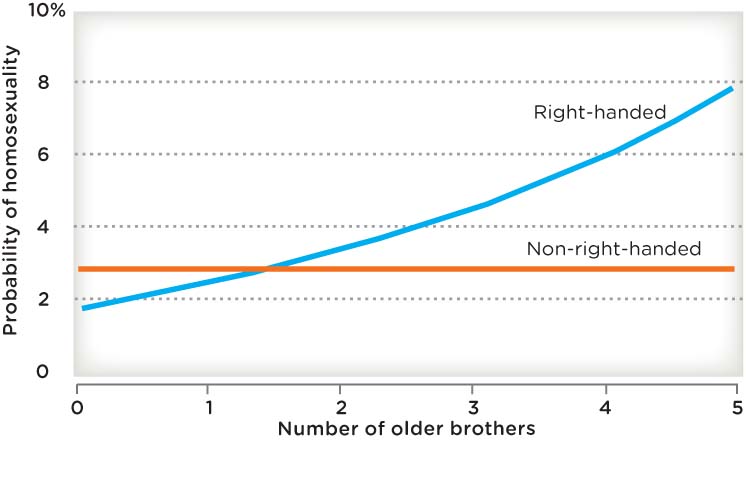

Interestingly, having older brothers in the family seems to be associated with homosexuality in men, particularly in right-handed men (Blanchard, 2008; Figure 10.4). Why would this be? Evolutionary theory would suggest that the more males there are in a family, the more potential for “unproductive competition” among the male siblings. If sons born later in the birth order were less aggressive, the result would be fewer problems among siblings, especially related to competition for mates and resources to support offspring. A homosexual younger brother would be less of a threat to an older brother than would a heterosexual younger brother.

How does right-handedness play a role? Researchers suggest that handedness might be related to the production of an anti-male antibody produced by the mother during pregnancy: “Some mothers may eventually become ‘immunized’ to a factor or substance important in male fetal development” (Bogaert, 2007, p. 141). The maternal immune hypothesis suggests that mothers develop an antibody that crosses the placenta and affects the development of the brain structures influencing sexual orientation (for example, the hypothalamus). Although subsequent research has supported the birth order effect, the handedness link has been more difficult to replicate (Bogaert, 2007). And, despite numerous attempts to identify genetic markers for homosexuality, researchers have had very little success (Dar-Nimrod & Heine, 2011). Some suggest that the search for genes underlying homosexuality is misguided. Why do we spend so much time and money seeking biological explanations for a “valid alternative lifestyle” (Jacobs, 2012)?

Bias

Although differences in sexual orientation are universal and have been evident throughout recorded history, individuals identified as members of the nonheterosexual minority have been subjected to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. Nonheterosexual people in the United States, for example, have been, and continue to be, subjected to harassment, violence, and unfair practices related to housing and employment.

Counter to some stereotypes, a homosexual or bisexual orientation does not serve as a barrier to maintaining long-lasting relationships. Most same-sex couples experience the same ups and downs as heterosexual couples. When San Francisco’s Mayor Gavin Newsom sanctioned same-sex marriages in the city in 2004, a number of long-partnered same-sex couples were finally able to legalize their relationships. Among those marrying long-time partners was Ronnie Gilbert, the female singer in The Weavers (famous for their song “Goodnight, Irene”), now in her eighties.

across the WORLD

Homosexuality and Culture

As you read earlier, approximately 3.5% of the U.S. population is gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and approximately 0.2% is transgender (Gates, 2011). These figures could be underestimates, as people may not always disclose their true sexual orientation to researchers.

As you read earlier, approximately 3.5% of the U.S. population is gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and approximately 0.2% is transgender (Gates, 2011). These figures could be underestimates, as people may not always disclose their true sexual orientation to researchers.

When it comes to studying homosexuality in some parts of the world—particularly in developing nations—the research is lacking. One group of researchers reviewed the scientific literature for articles addressing male homosexuality in various countries and found limited, if any, data for parts of Africa, the Middle East, and the English-speaking Caribbean (Cáceres, Konda, Pecheny, Chatterjee, & Lyerla, 2006). For those regions where data did exist, the researchers were able to calculate the following percentages of men who had sex with other men: East Asia, 3–5%; South and South East Asia, 6–12%; Eastern Europe, 6–15%; and Latin America, 6–20% (Cáceres et al., 2006). But in cultures where sex between men is taboo or forbidden, people tend to remain tight lipped about the phenomenon, and researchers may not even study it (Wellings et al., 2006).

…“SEX BETWEEN MEN” DOES NOT NECESSARILY EQUATE TO HOMOSEXUALITY.

As you consider these statistics, keep in mind that “sex between men” does not necessarily equate to homosexuality. In India, for example, young straight men have few outlets for their sexual energy because heterosexual sex outside of marriage is generally forbidden. In this context, having sexual relationships with other men does not automatically make one homosexual (Go et al., 2004). Similarly in the United States, “sex between women” does not always go hand-in-hand with being lesbian or bisexual. Concepts of sexual orientation depend on culture as well as individual attitudes and perceptions.

Evolutionary Psychology and Sex

What is the purpose of sex? Evolutionary psychology would suggest that humans have sex to make babies and ensure the survival of the species (Buss, 1995). But if this were the only reason, then why would so many people choose same-sex partners? Some researchers believe it has something to do with “kin altruism,” which suggests that homosexual men and women support reproduction in the family by helping relatives care for their children. Homosexual individuals may not “spend their time reproducing,” but they can nurture the reproductive efforts of their “kin” (Erickson-Schroth, 2010).

There are other reasons to believe that there is more to human sex than making babies. If sex were purely for reproduction, we would expect to see sexual activity occurring only during the fertile period of the female cycle. Obviously, this is not the case. People have sex throughout a woman’s monthly cycle and long after she goes through menopause. Sex is for feeling pleasure, expressing affection, and forming social bonds. In this respect, we are different from other members of the animal kingdom, who generally mate to procreate. There is at least one notable exception, however. If you could venture deep into the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo, you might be surprised at what you would see happening between our close primate cousins, the bonobos.

didn’t SEE that coming

Great Ape Sex

Bonobos are tree- and land-dwelling great apes that look like small and lanky versions of chimpanzees. And like chimps, these animals are closely related to humans, sharing 98.7% of our genetic material (Prüfer et al., 2012). Bonobos and people also happen to share some sexual behaviors.

Bonobos are tree- and land-dwelling great apes that look like small and lanky versions of chimpanzees. And like chimps, these animals are closely related to humans, sharing 98.7% of our genetic material (Prüfer et al., 2012). Bonobos and people also happen to share some sexual behaviors.

Bonobos have both oral sex and vaginal sex. They enjoy a variety of positions, including the so-called missionary style commonly employed by people. They French kiss and fondle each other. Males mate with females, but pairs of females also rub their genitals together, a phenomenon known as genito–genital rubbing, or G–G rubbing. Males engage in similar activities called scrotal rubbing and penis fencing (De Waal, 2009).

BONOBOS HAVE BOTH ORAL AND VAGINAL SEX.

In bonobo society, sex happens at the times you might least suspect. Imagine two female bonobos simultaneously discovering a delicious piece of sugar cane. Both of them want it, so you might expect a little aggression to ensue. But what do the bonobos do instead? They rub their genitals together, of course! Now picture two males competing for the same female. They could fight over her, but why fight when you can make love? The vying males set aside their dispute and engage in a friendly scrotal rub (De Waal, 2009).

As these examples illustrate, bonobo sex has a lot to do with maintaining social harmony. Sex is used to defuse the tension that might arise over competition for food and mates (De Waal, 2009). It helps younger females bond with the dominant females in a new community—an important function given the supremacy of females in this species (Clay & Zuberbühler, 2012). Female relationships, it seems, are the glue holding together bonobo society.

What kinds of similarities do you detect between the sex lives of bonobos and humans?

The Sex We Have

Thus far we have discussed sex in broad terms, but let’s get into some specifics. Have you ever wondered how common it is to masturbate or think about sex? Do you sometimes wonder how many married people remain faithful to their spouses? You have come to the right chapter.

The History of Sex Research

Alfred Kinsey and colleagues (1948, 1953) were among the first to try to scientifically and objectively examine human sexuality in America. Using the survey method, Kinsey and his team collected data on the sexual behaviors of 5,300 White males and 5,940 White females. Their findings were surprising; both men and women masturbated, and participants had experiences with premarital sex, adultery, and sexual activity with someone of the same sex. Perhaps more shocking was the fact that so many people were willing to talk about their personal sexual behavior in post–World War II America. At that time, people generally did not talk openly about sexual topics.

The Kinsey study was groundbreaking in terms of its data content and methodology, which included accuracy checks and assurances of confidentiality. The Kinsey data have served as a valuable reference for researchers studying how sexual behaviors have evolved over time. However, Kinsey’s work was not without limitations. For example, Kinsey and colleagues (1948, 1953) utilized a biased sampling technique that resulted in a sample that was not representative of the population. It was a completely White sample, with an overrepresentation of well-educated Protestants (Potter, 2006; Wallin, 1949). Another criticism of the Kinsey study is that it failed to determine the context in which orgasms occurred. Was a partner involved? Was the orgasm achieved through masturbation (Potter, 2006)?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we emphasized that representative samples enable us to generalize findings to populations. Here we see that inferences about sexual behaviors for groups other than White, well-educated Protestants could be problematic, as few members of these groups participated in the Kinsey study.

Subsequent research has been better designed, including samples more representative of the population. Robert Michael and colleagues (1994) conducted the now-classic National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS), which examined the sexual activities of a representative sample of some 3,000 Americans between the ages of 18 and 59. A more recent study included a sample of approximately 5,800 men and women between the ages of 14 and 94 years (Herbenick et al., 2010). Some of the findings from these studies are presented below. For more information on sexual activities worldwide, take a look at the Across the World feature.

Sexual Activity in Relationships

In the United States, the average age at first marriage is 26 for women and 28 for men. The odds of a first marriage lasting at least 10 years is 68% for women and 70% for men, and the probability of a first marriage lasting 20 years is only 52% for women and 56% for men (Copen, Daniels, Vespa, & Mosher, 2012). Most Americans are monogamous (one partner at a time), and 65–85% of married men and approximately 80% of married women report that they have always been faithful to their spouses (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). Although monogamy is preferred in the United States, infidelity within marriages is as high as 76%. In a recent study, 4–5% of the participants reported they are in “open” relationships, that is, consensually nonmonogamous relationships (Conley, Ziegler, Moors, Matsick, & Valentine, 2013).

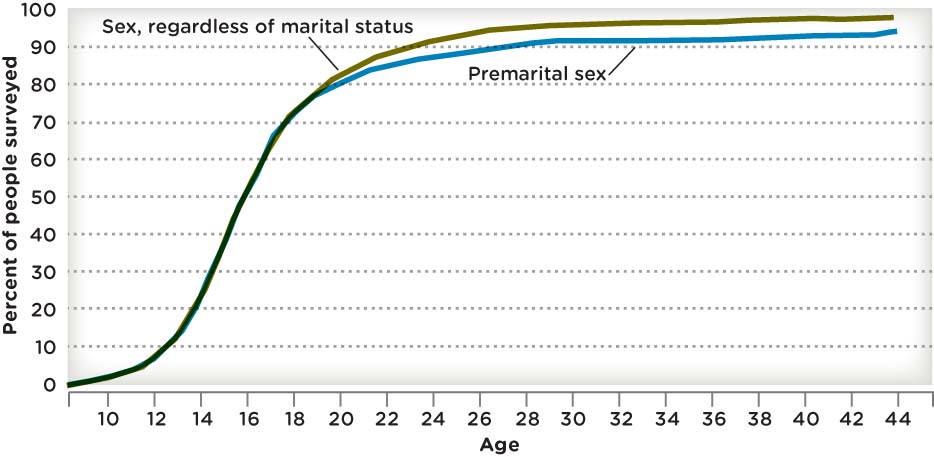

Around 77% of adults in the United States report they engaged in intercourse by age 20, regardless of cultural background or ethnicity. By the age of 44, 95% of adults have had intercourse. And the overwhelming majority are not waiting for marriage (Finer, 2007; see Figure 10.5.) However, married people do have more sex than those who are unmarried (Laumann et al., 1994). According to a large study of Swedish adults, the frequency of penile–vaginal intercourse is associated with sexual satisfaction, as well as satisfaction with relationships, mental health, and life in general. Other sexual activities, such as masturbation, were found to have an inverse relationship with a variety of measures of satisfaction (Brody & Costa, 2009; see TABLE 10.2 for reported gender differences in frequency of sexual activity). Many studies indicate not only psychological benefits, but also physiological benefits to penile–vaginal intercourse. Correlations are apparent between the frequency of penile–vaginal intercourse and greater life expectancy, lower blood pressure, slimmer waistline, and less prostate and breast cancer risk (Brody, 2010).

| Sexual Activity | Average Frequency in Prior Month for Men | Average Frequency in Prior Month for Women |

| Penile–vaginal intercourse | 5.2 | 4.8 |

| Oral sex | 2.3 | 1.9 |

| Anal sex | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Masturbation | 4.5 | 1.5 |

| How often do people engage in different types of sexual activity? Here are the monthly averages for adult men and women (the average age being 41). Keep in mind that significant variation exists around these averages. | ||

| SOURCE: BRODY AND COSTA (2009), TABLE 1, P. 1950. | ||

Sexual Activity and Gender Differences

As stereotypes might suggest, men think about sex more often than women. In the United States, 54% of men report thinking about sex “every day or several times a day”; 67% of women report thinking about sex only “a few times a week or a few times a month” (Laumann et al., 1994). One other notable gender difference is that men consistently report a higher frequency of masturbation (Peplau, 2003), a finding that has been replicated with a British sample (Gerressu, Mercer, Graham, Wellings, & Johnson, 2008). Men in the United States tend to be more tolerant than women when it comes to casual sex before marriage, as well as more permissive in their attitudes about extramarital sex (Laumann et al., 1994). But these attitude differences are not apparent in heterosexual teenagers and young adults, as young men and women more commonly engage in hookups, or “brief uncommitted sexual encounters among individuals who are not romantic partners or dating each other” (Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriwether, 2012, p. 161). For these young people, attitudes about casual sex are apparent in their “hookup” behavior (TABLE 10.3).

| Hookup Behavior | Undergraduates Reporting Behavior (%) |

| Kissing | 98 |

| Sexual touching above waist | 58 |

| Sexual touching below the waist | 53 |

| Performed oral sex | 36 |

| Received oral sex | 35 |

| Sexual intercourse | 34 |

| What exactly do college students mean when they say they “hooked up” with someone? As you can see from the data presented here, hooking up can signify anything from a brief kiss to sexual intercourse. | |

|

SOURCE: GARCIA ET AL. (2012). |

|

Sexual Activity and Age

What sexual encounters do people commonly have? Herbenick and colleagues (2010) used a cross-sectional survey study to provide a snapshot of the types and rates of sexual behaviors across a wide range of ages in the United States. They found that masturbation is more common than partnered sexual activities among adolescents and people over the age of 70. They also discovered that more than half of the participants aged 18 to 49 had engaged in oral sex in the past year, with a lower proportion of the younger and older age groups engaging in this activity. Penetrative sex (vaginal and anal) was most common among adults ages 20 to 49. In another study of around 3,000 adults (57 to 85 years old), researchers reported that aging did not seem to adversely affect interest in sexual activity; many of the respondents in their sixties, seventies, and eighties were still sexually active. In fact, through the age of 74, the frequency of sexual activity remained steady, even with a high proportion of “bothersome sexual problems.” Physical health problems can affect sexual activity at any age (Lindau et al., 2007).

across the WORLD

What They Are Doing in Bed…or Elsewhere

How often do people in New Zealand have sex? How many lovers has the average Israeli had? And are Chileans happy with the amount of love-making they do? These are just a few of the questions answered by the Global Sex Survey (2005), which, we dare to say, is one of the sexiest scientific studies out there (and which was sponsored by Durex, a condom manufacturer). We cannot report all the survey results, but here is a roundup of those we found most interesting:

How often do people in New Zealand have sex? How many lovers has the average Israeli had? And are Chileans happy with the amount of love-making they do? These are just a few of the questions answered by the Global Sex Survey (2005), which, we dare to say, is one of the sexiest scientific studies out there (and which was sponsored by Durex, a condom manufacturer). We cannot report all the survey results, but here is a roundup of those we found most interesting:

PEOPLE IN GREECE ARE HAVING THE MOST SEX.

- People in Greece have the most sex—an average of 138 times per year, or 2 to 3 times per week.

- People in Japan have the least amount of sex—an average of 45 times per year, or a little less than once per week.

- The average age for losing one’s virginity is lowest among Icelanders (between 15 and 16) and highest for those from India (between 19 and 20).

- Across nations, the average number of sexual partners is 9. If gender is taken into account, that number is a little higher for men (11) and lower for women (7).

- Of respondents, 50% reported having sex in cars, 39% in bathrooms, and 2% in airplanes.

- Across the world, many people use sexual aids such as pornography (41%), massage oils and creams (31%), lubricants (30%), and vibrators (22%).

- Approximately 13% of adults say they have had a sexually transmitted infection.

- Nearly half the people around the world are happy with their sex lives.

As you reflect on these results, remember that surveys have limitations. People are not always honest when it comes to answering questions about personal issues (like sex), and the wording of questions can influence people’s responses. Even if responses are accurate, we can only speculate about the beliefs and attitudes under-lying them.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed limitations of using self-report surveys. People often resist revealing attitudes or behaviors related to sensitive topics, such as sexual activity. The risk is gathering data that do not accurately represent participants’ attitudes and beliefs, particularly with face-to-face interviews.

Contemporary Trends in Sexual Behavior

As noted earlier, we can define sex as an activity (for example, she had sex), but how we define what constitutes sex is not always consistent (Schwarz, Hassebrauck, & Dörfler, 2010). If you ask one teenager whether she has had “sex,” she might say no, even if she has had oral sex, whereas another teen might say yes, thinking that oral sex does count as sex. Such variability may explain why teenagers are more likely to participate in oral sex than intercourse, and to have more oral sex partners because they are not defining it as sex (Prinstein, Meade, & Cohen, 2003).

If oral sex doesn’t qualify as “sex,” as some teenagers believe, then it doesn’t pose a health risk…right? Wrong. Many diseases can be transmitted through oral sex, among them HIV, herpes, syphilis, genital warts, and hepatitis (Saini, Saini, & Sharma, 2010). Needless to say, it is crucial for teen-targeted sex education programs to spread the word about the risks associated with oral sex (Brewster & Tillman, 2008).

THINK again

Sext You Later

What kinds of environmental factors do you think encourage casual attitudes about sex among teens? Most adolescents have cell phones these days (77%, according to one survey; Lenhart, 2012) and a large number of those young people are using their phones to exchange text messages with sexually explicit words or images. In other words, today’s teenagers are doing a lot of sexting. One study found that 20% of high school students have used their cell phones to share sexual pictures of themselves, and twice as many have received such images from others (Strassberg, McKinnon, Sustaíta, & Rullo, 2013). Teens who sext are more likely to have sex and take sexual risks, such as having unprotected sex (Rice et al., 2012).

What kinds of environmental factors do you think encourage casual attitudes about sex among teens? Most adolescents have cell phones these days (77%, according to one survey; Lenhart, 2012) and a large number of those young people are using their phones to exchange text messages with sexually explicit words or images. In other words, today’s teenagers are doing a lot of sexting. One study found that 20% of high school students have used their cell phones to share sexual pictures of themselves, and twice as many have received such images from others (Strassberg, McKinnon, Sustaíta, & Rullo, 2013). Teens who sext are more likely to have sex and take sexual risks, such as having unprotected sex (Rice et al., 2012).

Sexting carries another set of risks for those who are married or in committed relationships. As many people see it, sexting outside a relationship is a genuine form of cheating. And because text messages can be saved and forwarded, it becomes an easy and effective way to damage the reputations of people, sometimes famous ones. Perhaps you have read about the sexting scandals associated with golfer Tiger Woods, ex-footballer Brett Favre, and former U.S. Congressman Anthony Weiner?

ARE TEENS WHO SEXT MORE LIKELY TO HAVE SEX?

Now that’s a lot of bad news about sexting. But can it also occur in the absence of negative behaviors and outcomes? When sexting is between two consenting, or shall we say “consexting,” adults, it may be completely harmless (provided no infidelity is involved). According to one survey of young adults, sexting was not linked to unsafe sex or psychological problems such as depression and low self-esteem (Gordon-Messer, Bauermeister, Grodzinski, & Zimmerman, 2013). For some, sexting is just a new variation on flirting; for others, it may fulfill a deeper need, like helping them feel more secure in their romantic attachments (Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011).

Sex Education

One way to learn about this relatively new phenomenon of sexting—or any sexual topic, for that matter—is through sex education in the classroom. School is the primary place where American children get information about sex (Byers, 2011), yet it is somewhat controversial. Many parents are afraid that some types of sex education essentially condone sexual activity among young people. Until 2010, Title V federal funding was limited to states that taught abstinence only (Chin et al., 2012). Yet, research suggests that programs promoting abstinence are associated with more teenage pregnancies: States with a greater emphasis on abstinence (as reflected in state laws and policies) have higher teenage pregnancy and birth rates (Stanger-Hall & Hall, 2011).

Teenagers who are provided a thorough education on sexual activity, including information on how to prevent pregnancy, are less likely to become pregnant (or get someone pregnant). Research shows that formal sex education increases safe-sex practices, reducing the likelihood of disease transmission (Kohler, Manhart, & Lafferty, 2008; Stanger-Hall & Hall, 2011). Sex education clearly impacts the behaviors of teenagers and young adults. In some European nations, “openness” and “comfort” about sex lead to an understanding that sexuality is “a lifelong process.” Sex education programs in these countries aim “to create self-determined and responsible attitudes and behavior with regard to sexuality, contraception, relationships and life strategies and planning” (Advocates for Youth, 2009; Stanger-Hall & Hall, 2011, p. 9).

show what you know

Question 10.9

1. Masters and Johnson studied the physiological changes that accompany sexual activity. They determined that men and women experience a similar sexual response cycle, including the following ordered phases:

- excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution.

- plateau, excitement, orgasm, relaxation.

- excitement, plateau, orgasm.

- excitement, orgasm, resolution.

a. excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution.

Question 10.10

2. Some have suggested that “kin altruism” may explain how homosexual men and women contribute to the overall reproduction of the family, by helping to care for children of relatives. This explanation draws upon the __________ perspective.

evolutionary

Question 10.11

3. Explain how twin studies have been used to explore the development of sexual orientation.

Because monozygotic twins share 100% of their genetic make-up, we expect them to share more genetically influenced characteristics than dizygotic twins, who only share about 50% of their genes. Using twins, researchers explored the impact of genes and environment on same-sex sexual behavior. Monozygotic twins were moderately more likely than dizygotic twins to have the same sexual orientation. They found men and women differ in terms of the heritability of same-sex sexual behavior (34–39% for men, 18–19% for women). These studies highlight that the influence of the environment is substantial with regard to same-sex sexual behavior.

Question 10.12

4. __________ is the “enduring pattern” of sexual, romantic, and emotional attraction that individuals exhibit toward the same sex, opposite sex, or both sexes.

Sexual orientation

Question 10.13

5. A neuroscientist gives a lecture at a senior citizens center in which he describes what is known about the origins of sexual orientation. Which of the following might he report?

- Dizygotic twins have greater similarity in sexual orientation than monozygotic twins.

- Some brain structures, such as areas in the hypothalamus, have differences that correlate with sexual orientation.

- Sexual orientation is definitely a matter of choice.

- Sexual orientation results entirely from biological factors.

b. Some brain structures, such as the hypothalamus, have differences that correlate to sexual orientation.