11.2 Psychoanalytic Theories

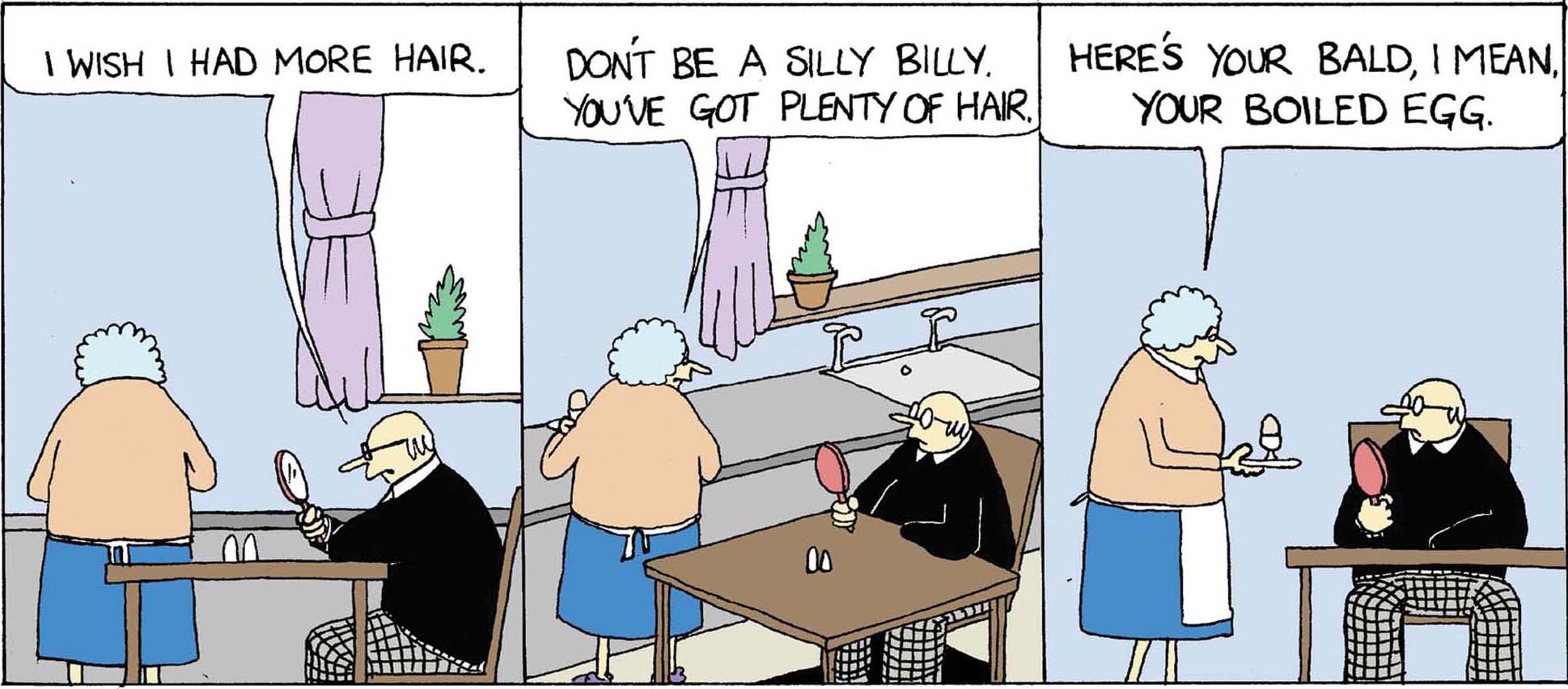

NEVER GOOD ENOUGH FOR DAD

Tank the Roboceptionist has quite a colorful past, thanks to the creative minds at Carnegie Mellon’s School of Drama, who carefully crafted his background to mesh with his current persona. Tank’s father was a NASA scientist who failed to fulfill his dream of becoming an astronaut. Unfortunately, dad focused his “unfinished business” onto his robot son, pressuring him to accomplish what he never did. Dad wanted Tank to be like the Hubble Space Telescope, able to fly into space and capture beautiful images of other planets and celestial bodies. But Tank turned out to be an utter failure. He got his coordinates mixed up and sent back photos of Earth. Tank’s father was so humiliated that he disowned him (Carnegie Mellon University, 2013).

Tank the Roboceptionist has quite a colorful past, thanks to the creative minds at Carnegie Mellon’s School of Drama, who carefully crafted his background to mesh with his current persona. Tank’s father was a NASA scientist who failed to fulfill his dream of becoming an astronaut. Unfortunately, dad focused his “unfinished business” onto his robot son, pressuring him to accomplish what he never did. Dad wanted Tank to be like the Hubble Space Telescope, able to fly into space and capture beautiful images of other planets and celestial bodies. But Tank turned out to be an utter failure. He got his coordinates mixed up and sent back photos of Earth. Tank’s father was so humiliated that he disowned him (Carnegie Mellon University, 2013).

If only we could ask Sigmund Freud what he thought of this father–son relationship—surely, he would have some interesting things to say. Freud believed childhood is the prime time for personality development. Early years and basic drives are particularly important, according to Freud, because they shape our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in ways beyond our awareness. Psychoanalysis refers to Freud’s views about personality as well as his system of psychotherapy and tools for the exploration of the unconscious. In this next section, we will present an overview of Freud’s psychoanalysis as it relates to personality and some of the later personality theories it influenced.

Many students have trouble understanding why we should study Freud, whose ideas they consider sexist, perverse, and outdated. Freud is an important historical figure in psychology, and we can’t ignore his legacy just because we disagree with him. You wouldn’t find many world history teachers ignoring Hitler in their coverage of the 1900s, would you? The same principle applies to Freud; his impact was huge and cannot be overlooked.

Freud and the Mind

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) spent the majority of his life in Vienna, Austria. He was his parents’ first child and quite favored by his mother (Gay, 1988). A smart, ambitious young man, Freud attended medical school and became a physician and researcher with a primary interest in physiology and later neurology. Freud loved doing research, but he soon came to realize that the anti-Semitic culture in which he lived would drastically interfere with his ability to work as a researcher (Freud was Jewish). So, instead of pursuing the career he loved, he opened a medical practice in 1881, specializing in clinical neurology. Working with patients, he noted that many had unexplained or unusual symptoms that seemed related to emotional problems. He also observed (along with colleagues) that the basis of the problems appeared to be sexual in nature, although his patients weren’t necessarily aware of this influence (Freud, 1900/1953). Thus began Freud’s lifelong journey to untangle the mysteries of the unconscious mind.

Conscious, Preconscious, And Unconscious

LO 3 Illustrate Freud’s models for describing the mind.

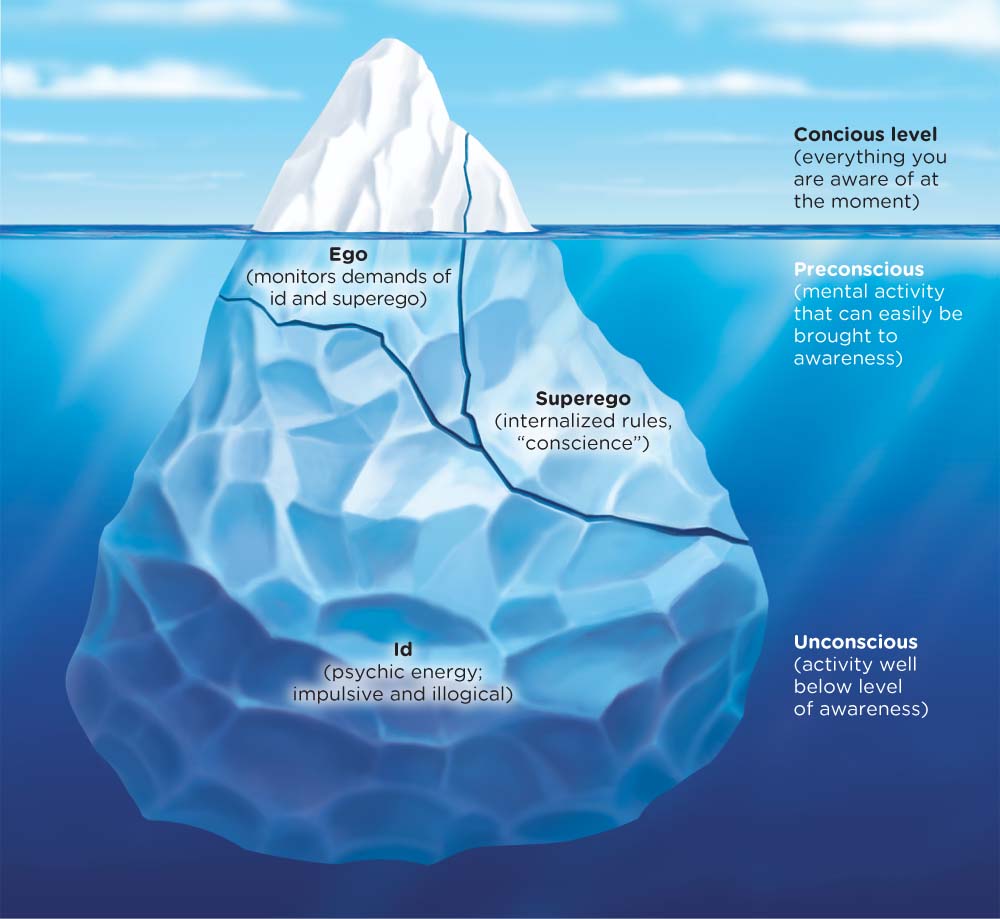

Freud (1900/1953) proposed that the mind has three levels of consciousness: conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. This so-called iceberg model, or topographical model, was his earliest attempt to explain the bustling activity occurring within the head (Westen, Gabbard, & Ortigo, 2008). It describes the features of the mind (which explains the reference to topography), and many who subsequently have presented this model use an iceberg analogy to portray these levels (Schultz & Schultz, 2013; Figure 11.1).

Freud believed that behaviors and personality are guided by mental processes occurring at all three levels of the mind. Everything you are aware of at this moment exists at the conscious level, including thoughts, emotions, sensations, and perceptions. At the preconsciouslevel are the mental activities outside your current awareness, but that can be brought easily to your attention. (You are studying Freud’s theory at this moment, but your mind begins to wander and you start thinking about what you did yesterday.) The unconscious level is home to activities outside of your awareness, such as feelings, wishes, thoughts and urges, which are very difficult to access without concerted effort and/or therapy. To gain access to the unconscious level, Freud (1900/1953) used a variety of techniques, such as dream interpretation (Chapter 4), hypnosis (Chapter 4), and free association (Chapter 14). Freud did suggest, however, that some content of the unconscious can enter the conscious level through manipulated and distorted processes beyond a person’s control or awareness (more on this shortly).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 6, we presented the concept of episodic buffer (a component of working memory), which forms a bridge between memory and conscious awareness. Although Freud did not refer to such a buffer, the preconscious level includes activities somewhat similar to those of the episodic buffer.

Id, Ego, and Superego: The Structural Model of the Mind

In addition to the topographical model, Freud proposed a structural model, which describes the “functions or purposes” of the mind’s components (Westen et al., 2008, p. 65). As Freud saw it, the human mind is composed of three structures: the id, the ego, and the superego (Figure 11.1). These components lie at the core of the unconscious conflicts influencing our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors—that is, our personality (Westen et al., 2008).

The ID

The id is the most primitive structure of the mind. It is present from birth, and its activities occur at the unconscious level. The infantlike part of our mind and personality (being impulsive, illogical, pleasure seeking) results from the workings of the id. Our biological drives and instincts, which motivate us, derive from the id. Freud proposed that the id represents the component of the mind that forms the primary pool of psychic energy (Freud, 1923/1961, 1933/1964). Included in that pool is sexual energy, which motivates much of our behavior. The primary goal of the id is to ensure that the individual’s needs are being met, helping to maintain homeostasis. The id is not rational; it is impulsive, and it wants what it wants when it wants it. Unfilled needs or urges compel the id to insist on immediate action. The id is ruled by the pleasure principle, which guides behavior toward instant gratification—and away from contemplating consequences. The id seeks pleasure and avoids pain.

CONNECTIONS

Meeting the demands of the id is similar to the concept of drive reduction discussed in Chapter 9. If a need is not fulfilled, a drive or a state of tension results that motivates behavior. Once the need is met, the drive is reduced. According to Freud’s model, the id is in charge of making sure needs are met.

The Ego

As an infant grows and starts to realize that the desires of the id cannot prevail in all situations, her ego, which is not present from birth, begins to develop from the id (Freud, 1933/1964, 1940/1949). The ego manipulates situations, plans for the future, solves problems, and makes decisions to satisfy the needs of the id. The goal is to make sure that the id is not given free rein to decide on or steer behavior, as this would cause problems. To control the psychic energy generated by the id, the ego must “negotiate” between the desires of the id and the requirements of real life. Adults know they can’t always get what they want when they want it, but the id does not know or care. Imagine what a busy supermarket would be like if we were all ruled by our ids, ignoring societal expectations to stand in line, speak politely, and pay for food; the store would be full of adults having toddlerlike tantrums. The ego uses the reality principle to negotiate between the id and the environment. This requires knowledge of the rules of the “real” world and allows most of us to delay gratification as needed (Freud, 1923/1960). The reality principle works through an awareness of potential consequences; the ego can predict what will happen if we act on an urge. One suggestion is that the ego represents what we consider the self (Freud, 1923/1960)—that is, the self of which we are consciously aware. We are aware of the ego’s activities, although some happen at the preconscious level, and even fewer at the unconscious level (Figure 11.1).

The Superego

The superego is the structure of the mind that develops last, guiding behavior to follow the rules of society, parents, or other authority figures (Freud, 1923/1960). The superego begins to form as the toddler starts moving about on his own, coming up against rules and expectations (No, you cannot hit your sister! You need to put your toys away.). Around age 5 or 6, the child begins to incorporate the morals and values of his parents or caregivers, including their expectations and ideas about right and wrong, colloquially known as the conscience. Once the superego is rooted, it serves as a critical internal guide to the values of society (not just those of the parents), so that the child can make “good” choices without constant reminders from a parent, caregiver, or religious leader. The rules and expectations now come from an internal voice citing right and wrong. Yet at times, the superego might serve as a harsh and judgmental voice in response to the unrealistic standards it has set. The superego is an internalized version of what you have been taught is right and wrong, not necessarily an independent moral authority. Some of the activities of the superego are conscious, but the great majority occur at the preconscious and unconscious levels.

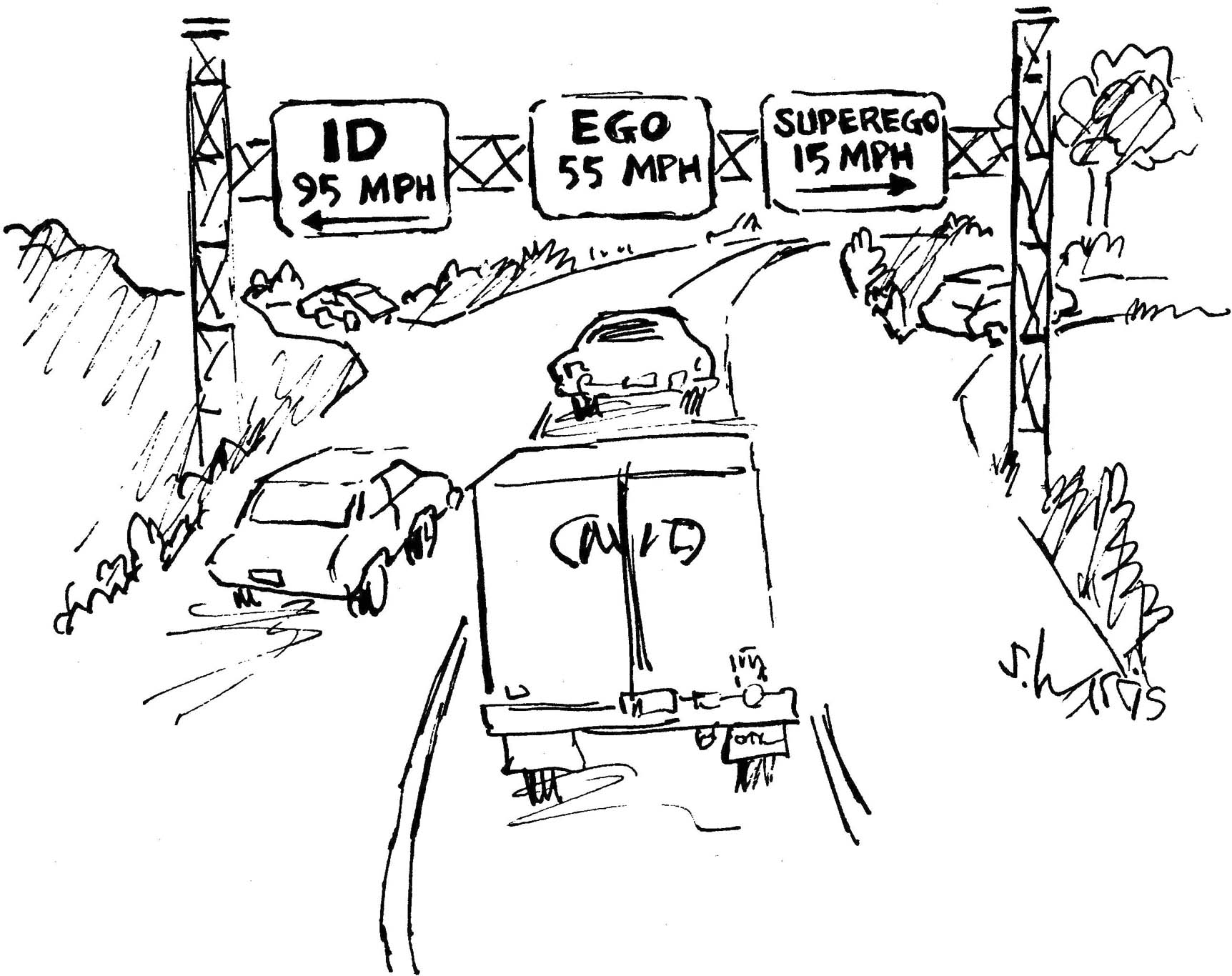

Caught In The Middle

The ego monitors the demands of both the id and the superego, trying to satisfy both. Rules and expectations must be dealt with by the ego, as it maneuvers between the wishes of the id and the requirements and limits set by the environment. Think of the energy of the id, pushing to get all desires met instantly. The ego must ensure needs are met in an acceptable manner, reducing tension as much as possible. But not all urges and desires can be met (sometimes not instantly, sometimes never), so when the ego cannot satisfy the id, it must do something with the unsatisfied urge or unmet need. One solution is to remove it from the conscious part of the mind.

Defense Mechanisms

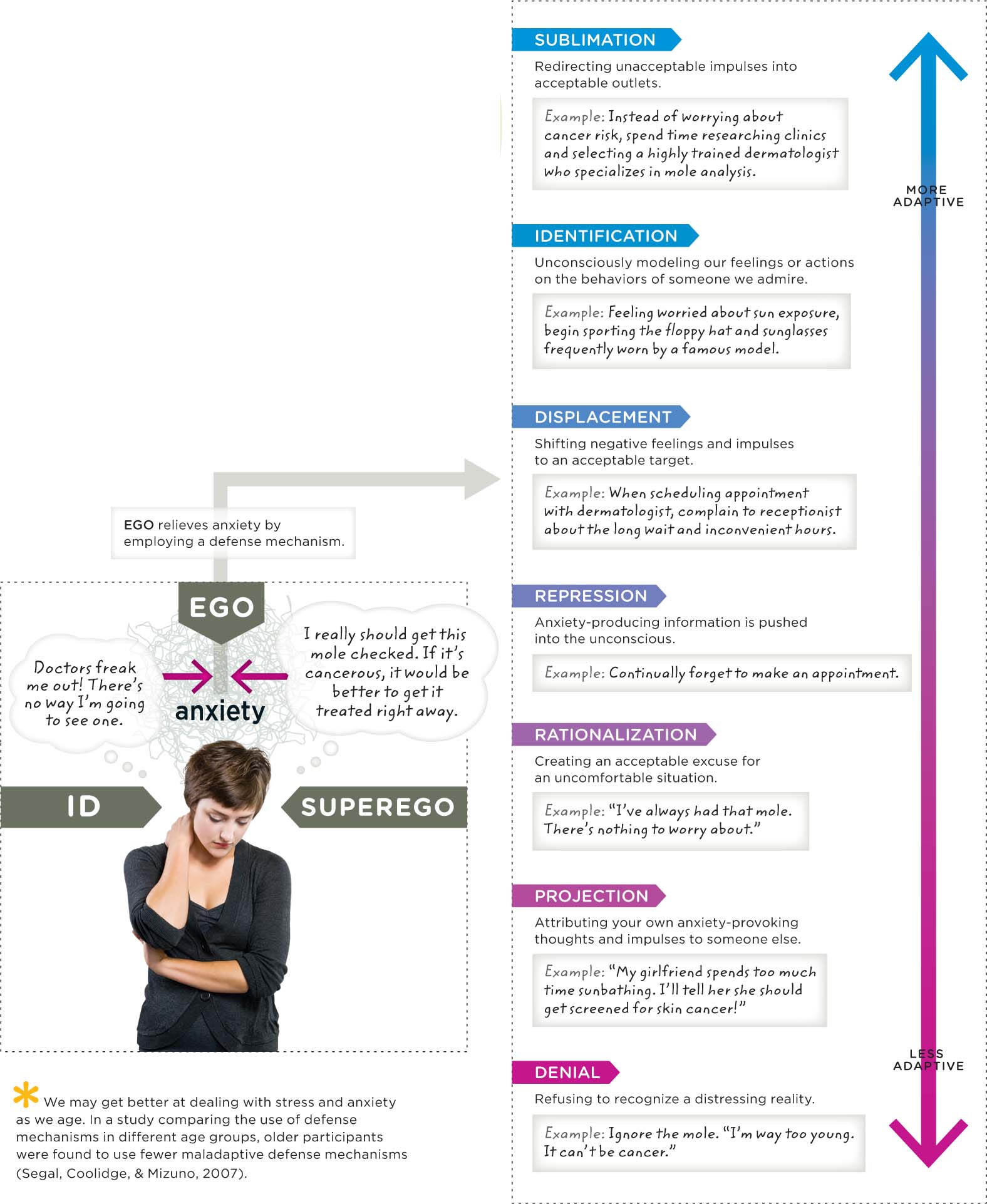

As you have figured out by now, the job of the ego is not easy. It must balance the infantile demands of the id with the perfectionist authority of the superego, and deal with the resulting conflict. This is feasible, but it takes some fancy footwork on the part of the ego. Freud proposed that ego defense mechanisms distort our perceptions and memories of the “real” world, without our awareness, to reduce the anxiety created by the conflicts among the id, ego, and superego.

Imagine you are about to leave for class and a good friend texts to invite you to a movie. You are torn, because you know an exam for the course is coming up next week and you should not skip today’s class. Your id is demanding a movie, some popcorn, and freedom from work. Your superego demands that you go to class so that you will be fully prepared for the exam next week. Clearly, your ego can’t satisfy both of these demands. The ego must also deal with the external world and its requirements (for example, getting points for attendance). Freud (1923/1960) proposed that this sort of struggle is an everyday, recurring experience that is not always won by the ego. Sometimes, the id will win, and the person will act in an infantile, perhaps even destructive manner (you give in to the pressures of your friend and your id, and happily decide to skip class). Occasionally, the superego will prevail, and the person will feel a great deal of remorse or guilt for not living up to some moral ideal (you skip class, but the entire time you are at the movie you feel so guilty you aren’t able to enjoy it). Sometimes, the anxiety associated with the conflict between the id and the superego, which generally is unconscious, will surface to the conscious level. The ego will then have to deal with this anxiety and make it more bearable (perhaps by suggesting that a day off will help you study, because you haven’t had any free time all semester). More often than not, the ego must come up with a way to decrease the tension. If the ego can’t find a compromise, the anxiety may become overwhelming, and the ego will turn to defense mechanisms to reduce it.

Projection is a defense mechanism that occurs when the expression of a thought or urge is so anxiety provoking that the ego makes us see it in someone else or accuse another of harboring these same urges. For example, if you are attracted to someone, but this attraction causes you a lot of anxiety, you may project that feeling onto your friend and ask her, “Oh, you really like Tai, don’t you?” Freud proposed a variety of other defense mechanisms, which were expanded upon by his daughter, Anna Freud. Some of these are shown in Infographic 11.1 (on page 474).

Repression

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 6, we presented the controversy surrounding repressed memories of childhood abuse. Many psychologists question the validity of research supporting the existence of repressed memories. Freud’s case studies describing childhood sexual abuse have been questioned as well.

Probably the defense mechanism best known by the general public is repression, which refers to the way the ego moves uncomfortable thoughts, memories, or feelings from the conscious level to the unconscious. With anxiety-provoking memories, the reality of an event can become distorted to such an extreme that you don’t even remember it. Someone involved in a bad car accident, for example, might have unconsciously or automatically repressed the memories surrounding the traumatic event. The ego moves the memory from the conscious to the unconscious so that the person can function day-to-day without anxiety from the accident surfacing into consciousness. Repressed thoughts are like ping-pong balls held below the surface of the water. As long as you hold them down, they stay submerged; but if you let go, they pop up to the surface. The balls didn’t cease to exist—they were simply just below the surface, out of sight and mind.

INFOGRAPHIC 11.1: Ego Defense Mechanisms

The impulsive demands of the id sometimes conflict with the moralistic demands of the superego, resulting in anxiety. When that anxiety becomes a source of tension, the ego works to relieve this uncomfortable feeling through the use of defense mechanisms (Freud, 1923/1960). Defense mechanisms give us a way to “defend” against tension and anxiety, but they are only sometimes adaptive, or helpful. Defense mechanisms can be categorized ranging from less adaptive to more adaptive (Vaillant, 1992). More adaptive defense mechanisms help us deal with our anxiety in more productive and mature ways.

There are two important points to remember about defense mechanisms. First, we are often unaware of using them, even if they are brought to our attention. Second, using defense mechanisms is not necessarily a bad thing (Vaillant, 2000). There are times when it helps to have reality distorted; for example, when anxiety seeps to the surface, defense mechanisms can bring it down to a more manageable level. But sometimes conflicts between the id and the superego are overwhelming, the anxiety is too much for the ego, and we overuse defense mechanisms. If this is the case, our behaviors may turn inappropriate or unhealthy (Cramer, 2000, 2008; Tallandini & Caudek, 2010).

Freud’s Stages of Development

LO 4 Summarize Freud’s use of psychosexual stages to explain personality.

Freud (1905/1953) also conceived a developmental model to explain how personality is formed through experiences in childhood, with a special emphasis on sexuality. The development of sexuality and personality follows a fairly standard path through what Freud termed the psychosexual stages, which all children experience as they mature into adulthood (TABLE 11.2). The sexual energy of the id is a force behind this development, and because children are sexual beings starting from birth, this indicates a strong biological component to personality development. Associated with each of the psychosexual stages is a specific erogenous zone, or area of the body that when stimulated provides more sexual pleasure than other areas of the body.

| Stage | Age | Erogenous Zone | Focus | Types of Conflict | Results of Fixation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Birth–1½ years | Mouth | Sucking, chewing, and gumming | Weaning | Smoking, drinking, nail biting, talking more than usual |

| Anal | 1½–3 years | Anus | Eliminating bodily waste and controlling bodily functions responsible for them | Toilet training | Rule-bound, stingy, chaotic, destructive |

| Phallic | 3–6 years | Genitals | Sexual feelings and awareness of self | Autoeroticism | Promiscuity, flirtation, vanity, or overdependence, and a focus on masturbation |

| Latency Period | 6 years–puberty | Period during which children develop mentally, socially, and physically | |||

| Genital | Puberty and beyond | Genitals | Reawakening of sexuality, with focus on relationships | Sexuality and aggression | Inability to thrive in adult activities such as work and love |

| According to Freud, psychological and sexual development proceeds through distinct stages. Each stage is characterized by a certain pleasure area, or “erogenous zone,” and a conflict that must be resolved. If resolution is not achieved, the person may develop a problematic “fixation.” | |||||

If the idea of a preschooler getting sexual pleasure from a body part makes you uncomfortable, then you are experiencing firsthand the child’s feeling of conflict between pleasurable sexual feelings and the restrictions and potential disapproval of caregivers. Along with each psychosexual stage comes a conflict, and these must be successfully resolved in order for an individual to become a well-adjusted adult. If these conflicts are not suitably addressed, one may suffer from a fixation and get stuck in that particular stage, unable to progress smoothly through the remaining stages. Freud believed that fixation at a psychosexual stage during the first 5 to 6 years of life can dramatically influence an adult’s personality. Let’s look at each stage, its erogenous zone, conflicts, and some consequences of fixation.

The Oral Stage

The oral stage is the first psychosexual stage, beginning at birth and lasting until the infant is 1 to 1.5 years old. As its name suggests, the erogenous zone for this stage is the mouth. During this period, the infant gets his greatest pleasure from sucking, chewing, and gumming. According to Freud, the conflict during this stage generally centers on weaning. Infants must stop nursing or using a bottle or pacifier, and the timing of this weaning often is decided by the caregiver. Here is a possible conflict: The infant wants to continue using the bottle because it is a pleasurable activity, but his parent believes he is old enough to switch to a cup. How the caregiver handles this conflict can have long-term consequences for personality development. Freud suggested that certain behavior patterns and personality traits are associated with an oral fixation, including smoking, nail biting, and excessive talking and alcohol consumption.

The Anal Stage

Following the oral stage, a child enters the anal stage, which lasts approximately until the age of 3. During this stage, the erogenous zone is the anus, and pleasure is derived from eliminating bodily waste as well as learning to control the body parts responsible for this process. The conflict during this stage centers on toilet training: The parents want their child to control her waste elimination in a socially acceptable way, but the child is not necessarily on board with this new procedure for doing so. Once again, how caregivers deal with this learning task may have long-term implications for personality. Freud suggested that toilet training can set the stage for power struggles between child and adult; the child ultimately will gain control over her bodily functions, and then she can use this control to manipulate caregivers (not always “going” at the appropriate time and place). If a parent is too harsh about toilet training (growing angry when there are accidents, forcing a child to sit on the toilet until she goes) or too lenient (making excuses for accidents, not really encouraging the child to learn control), the child might grow up with an anal-retentive personality (rule-bound, stingy) or an anal-expulsive personality (chaotic, destructive).

Phallic Stage

Age 3 to 6 marks the phallic stage (phallus means “penis” in Latin, and as you will see, Freud’s original theory of development is somewhat male-centered). During this period, the erogenous zone is the genitals, and many children begin to discover that self-stimulation is pleasurable. Freud (1923/1960) assigned special importance to the conflict that occurs in the phallic stage.

During this time, little boys develop a desire to replace their fathers. These feelings are normal, according to Freud, but they lead to boys becoming jealous of their fathers, who are now considered rivals for their mothers’ affection. This pattern, referred to as the Oedipus complex (e-də-pəs), is named for a character in a complex Greek myth. Oedipus was abandoned by his parents when he was a newborn, so he did not know their identities. As an adult, he unknowingly married his mother and killed his father. Freud named the behavior pattern of the phallic stage after the Greek tragedy, as how boys behave and feel during this period seems to follow such a pattern. When a little boy becomes aware of his attraction to his mother, he realizes his father is a formidable rival and experiences jealousy and anger toward him. He also begins to fear his father, who is so powerful, and worry that his father might punish him. Specifically, he fears that his father will castrate him (Freud, 1917/1966). In order to reduce the tension, the boy must identify with and behave like his father, a process otherwise known as identification. This defense mechanism resolves the Oedipus complex by allowing the boy to take on or internalize the behaviors, gestures, morals, and standards of his father. Freud proposed that the fear of castration causes a great deal of anxiety, but with successful resolution of the Oedipus complex, this anxiety is repressed. The boy realizes that sexual affection should only be between his father and mother, and the incest taboo develops.

Freud (1923/1960) believed that little girls experience a different conflict, which others refer to as the Electra complex. Little girls feel an attraction to their fathers, and become jealous and angry toward their mothers. Around the same time, they realize that they do not have a penis. This leads to feelings of loss and jealousy, known as penis envy. The girl responds with anger, blaming her mother for her missing penis. Realizing she can’t have her father, she begins to act like her mother, a process again known as identification. She takes on her mother’s behaviors, gestures, morals, and standards. Freud’s theory of female development is now regarded as a product of its historical and social context, as opposed to objective observation.

If children do not resolve the sexual conflicts that arise during the phallic stage, they develop a fixation, which can lead to promiscuity, flirtation, vanity, overdependence, bravado, and an increased focus on masturbation.

Latency Period

Freud proposed that from 6 years old to puberty, children remain in a latency period (not a “stage” according to Freud’s definition; there is no erogenous zone, no conflict, no fixation). During this time, psychosexual development slows. Where does the child’s sexual energy go during this period? According to Freud, it is repressed: Although children develop mentally, socially, and physically, their sexual development is on hold. This idea seems to be supported by the fact that most prepubertal children tend to gravitate toward same-sex friends and playmates.

Genital Stage

Following the calm of the latency period, a child’s psychosexual development picks up speed again. The genital stage begins at puberty and is the final stage of psychosexual development. During this time, there is a reawakening of sexuality. The erogenous zone is centered on the genitals, but now in association with relationships, as opposed to autoeroticism or masturbation. Adolescents become interested in partners, whereas earlier their focus was family members. This is a time when one resolves the Oedipus or Electra complex and often becomes attracted to partners who resemble one’s opposite-sex parent, according to Freud (1905/1953). Because of the ever-present id and its requirement for satisfaction, there still are unconscious conflicts to be addressed, including the continual battle against unconscious sexual and aggressive urges. The resolution of these conflicts impacts the types of relationships we seek and cultivate. If earlier conflicts are put to rest, then it is possible to thrive in adult activities such as work and love.

Taking Stock: An Appraisal of Psychoanalytic Theory

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory has been the subject of much criticism (Bornstein, 2005). Some of Freud’s own followers (a few of whom we will discuss shortly) recognized several key weaknesses. For example, psychoanalysis does not take into account the possibility that people can change; we are not predestined to develop certain personality types simply because we had specific experiences in childhood. Similarly, psychoanalysis ignores the importance of current development. Critics also contend that Freud placed too much weight on the unconscious forces guiding behavior, instead proposing that we can be conscious of our motivations and change our behaviors. Finally, many have objected to Freud’s emphasis on sexuality and its role in personality development.

Given the amount of attention Freud’s concepts have received, one might expect there is a great deal of research supporting or refuting aspects of his theory. But where would a researcher start? For example, how would you go about designing an experiment to test whether early weaning causes later problems in relationships? How about persuading an ethics committee to approve a study with an independent variable that manipulates toilet training? Given these types of difficulties, it is no surprise there is relatively little published research on Freudian concepts.

Another serious concern regarding psychoanalysis is that much of Freud’s theory is based on a biased, nonrepresentative sample (a handful of middle- and upper-class Viennese women and Freud himself), although more recent research attempts to address this issue (Shedler, 2010). Many feminists have raised concerns about Freud’s one-sided male perspective, although not necessarily dismissing potential usefulness of psychoanalysis to women (Young-Bruehl, 2009).

TANK’S ONGOING TROUBLES

Let’s return to the fictitious backstory of Tank the Roboceptionist for a moment. What happened to our robot after he was kicked to the curb by his father? He got a job with the CIA, which ended in another great failure. The agency shipped Tank to Afghanistan to fight in the war against terror, but his performance was so poor that he was sent home. As luck had it, Carnegie Mellon University was looking to hire a new roboceptionist around this time. Valerie, the robot who occupied the post, was about to abandon her administrative career and pursue her longtime dream of touring with a Barbra Streisand cover band. Tank accepted the roboceptionist position, which he has held since 2005 (Carnegie Mellon University, 2013).

Let’s return to the fictitious backstory of Tank the Roboceptionist for a moment. What happened to our robot after he was kicked to the curb by his father? He got a job with the CIA, which ended in another great failure. The agency shipped Tank to Afghanistan to fight in the war against terror, but his performance was so poor that he was sent home. As luck had it, Carnegie Mellon University was looking to hire a new roboceptionist around this time. Valerie, the robot who occupied the post, was about to abandon her administrative career and pursue her longtime dream of touring with a Barbra Streisand cover band. Tank accepted the roboceptionist position, which he has held since 2005 (Carnegie Mellon University, 2013).

Tank’s story is the intelligent invention of playwrights, but its basic themes are familiar to many. Parents often make the mistake of developing unrealistic expectations for their children, potentially setting them up for failure. According to the imaginary storyline, Tank’s father longed for him to replace the Hubble Space Telescope, but did he ever ask Tank what he wanted out of life?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced the case study, a form of descriptive research. A major weakness of the case study is its failure to provide a representative sample, or sample whose characteristics reflect the population. Freud’s case studies focused on a particular subgroup, thus his findings might not be generalizable.

According to Freud, personality is largely shaped by early childhood experiences and sexual impulses. But some of the most defining experiences in Tank’s life—like being abandoned by his father and bungling his mission with the CIA—occurred later in life and had nothing to do with sex. Some personality theorists might argue that these types of nonsexual experiences are important factors in the development of personality. We now turn to the neo-Freudians, who agree with Freud on many points, but depart from his intense emphasis on early childhood experiences and sexuality.

The Neo-Freudians

LO 5 Explain how the neo-Freudians’ theories of personality differ from Freud’s.

CONNECTIONS

Although he considered himself a “loyal Freudian,” Erik Erikson took Freud’s ideas in a new direction (Schultz & Schultz, 2013). As noted in Chapter 8, Erikson suggested psychosocial development occurs throughout life, with eight stages marked by a conflict between the individual’s needs and society’s expectations.

Not surprisingly, Freud’s psychoanalytic theory was quite controversial, but he did have a following of students who adapted some of the main aspects of his theory. Some who disagreed with Freud on key points (such as his focus on sex, aggression, and the determination of personality by the end of childhood) broke away to develop their own theories; they are often referred to as neo-Freudians (neo = “new”).

Alfred Adler

One of the first followers to forge his own path was Alfred Adler (1870–1937), whose own theory conflicted with the Freudian notion that personality is, to a large degree, shaped by unconscious motivators. As Adler saw it, humans are not just pleasure seekers, but conscious and intentional in their behaviors. We are motivated by the need to feel superior—to grow, overcome challenges, and strive for perfection. This drive originates during childhood, when we realize that we are dependent on and inferior to adults. Whether imagined or real, the sense of inferiority pushes us to compensate, so we cultivate our special gifts and skills. This attempt to balance perceived weaknesses with strengths is not a sign of abnormality, but a natural response.

Adler’s theory of individual psychology focuses on each person’s unique struggle with feelings of inferiority. Unfortunately, not everyone is successful in overcoming feelings of helplessness and dependence, but instead develop what is known as an inferiority complex (Adler, 1927/1994). Someone with an inferiority complex feels incompetent, vulnerable, and powerless, and cannot achieve his full potential. Based on what you know about Tank, would you say he has been programmed to resemble someone who suffers from an inferiority complex?

Perhaps you can imagine how an inferiority complex might play out in sibling relationships. The firstborn child receives all his parents’ attention for the first years of life. Then along comes a baby brother or sister, and suddenly mom and dad must divide their attention. How might this affect the older child’s sense of worth? Younger siblings have their own reasons for feeling inferior. They are, after all, the newcomers, smaller and less developed than their older siblings. And unlike the firstborn, who enjoyed being an only child for some time, younger siblings never had that special time with mom and dad. They always had to share their parents’ love.

Adler was one of the first to theorize about the psychological repercussions of birth order. He believed that first born children experience different environmental pressures than youngest and middle children, and these pressures can set the stage for the development of certain personality traits (Ansbacher & Ansbacher, 1956).

CONTROVERSIES

How Birth Order May—or May Not—Affect Your Personality

Firstborns are conscientious and high achieving. They play by the rules, excel in school, and become leaders in the workforce. The youngest children, favored and coddled by their parents, grow up to be gregarious and rebellious. Middle children tend to get lost in the shuffle, but they learn to be self-sufficient.

Firstborns are conscientious and high achieving. They play by the rules, excel in school, and become leaders in the workforce. The youngest children, favored and coddled by their parents, grow up to be gregarious and rebellious. Middle children tend to get lost in the shuffle, but they learn to be self-sufficient.

Have you heard these stereotypes about birth order and personality? How well do they match your personal experience, and do you think they are valid?

If you search the scientific literature, you will indeed find research supporting such claims. According to one analysis of 200 studies, firstborns (as well as only children) are often accomplished and successful; middle children are sociable but tend to lack a sense of belonging; and last-born children are agreeable and rebellious (Eckstein et al., 2010). You will also find plenty of skepticism regarding such findings (Ernst & Angst, 1983; Hartshorne, 2010).

There are over 2,000 scientific papers published on the birth order–personality connection, but it is still an active area of scholarly debate (Eckstein et al., 2010; Hartshorne, Salem-Hartshorne, & Hartshorne, 2009; Healey & Ellis, 2007). One of the problems with birth order studies is that they tend to be cluttered with confounding variables. Hartshorne (2010) points to the confounding variable of family size: We know that firstborn children are high achievers, but firstborns are also more likely to come from smaller families. Just think about it: The chances of being a firstborn are much greater if you come from a family with two children (1 in 2), as opposed to a family with four children (1 in 4). This makes it difficult to determine which variable is driving high achievement—being a firstborn or coming from a small family (Hartshorne, 2010).

MIDDLE CHILDREN TEND TO GET LOST IN THE SHUFFLE….

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed confounding variables, which are a type of extraneous variable that changes in sync with an independent variable (IV). Here, the IV is birth order, the confounding variable is family size, and the dependent variable (DV) is a measure of high achievement. But we don’t know if differences in achievement (DV) are due to birth order (IV) or family size (confounding variable).

We cannot resolve this longstanding debate here, but we can lighten the discussion with some interesting bits of information: Oprah Winfrey was a first child, as were most American presidents (Neal, 2009, February 11). Jim Carrey and Cameron Diaz are the youngest of their siblings, and Madonna and Miley Cyrus are middle children, as was Charles Darwin (MSN.com, 2012; Zupek, 2008, October 22). Given what you know about these famous people, are these revelations what you would expect?

Carl Gustav Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; 1875–1961) was another influential neo-Freudian. Jung’s focus was on growth and self-understanding. Although he agreed with Freud about the importance of the unconscious, in his analytic psychology he placed less emphasis on biological urges (sex and aggression), proposing more positive and spiritual aspects of human nature. Critical of Freud’s overemphasis on the sex drive, Jung claimed that Freud viewed the brain as “an appendage to the genital glands” (Westen et al., 2008, p. 66). Jung (1969) proposed we are driven by psychological energy (not sexual energy) that promotes growth, insight, and balance. He also believed personality development is not limited to childhood; adults continue to evolve throughout life.

; 1875–1961) was another influential neo-Freudian. Jung’s focus was on growth and self-understanding. Although he agreed with Freud about the importance of the unconscious, in his analytic psychology he placed less emphasis on biological urges (sex and aggression), proposing more positive and spiritual aspects of human nature. Critical of Freud’s overemphasis on the sex drive, Jung claimed that Freud viewed the brain as “an appendage to the genital glands” (Westen et al., 2008, p. 66). Jung (1969) proposed we are driven by psychological energy (not sexual energy) that promotes growth, insight, and balance. He also believed personality development is not limited to childhood; adults continue to evolve throughout life.

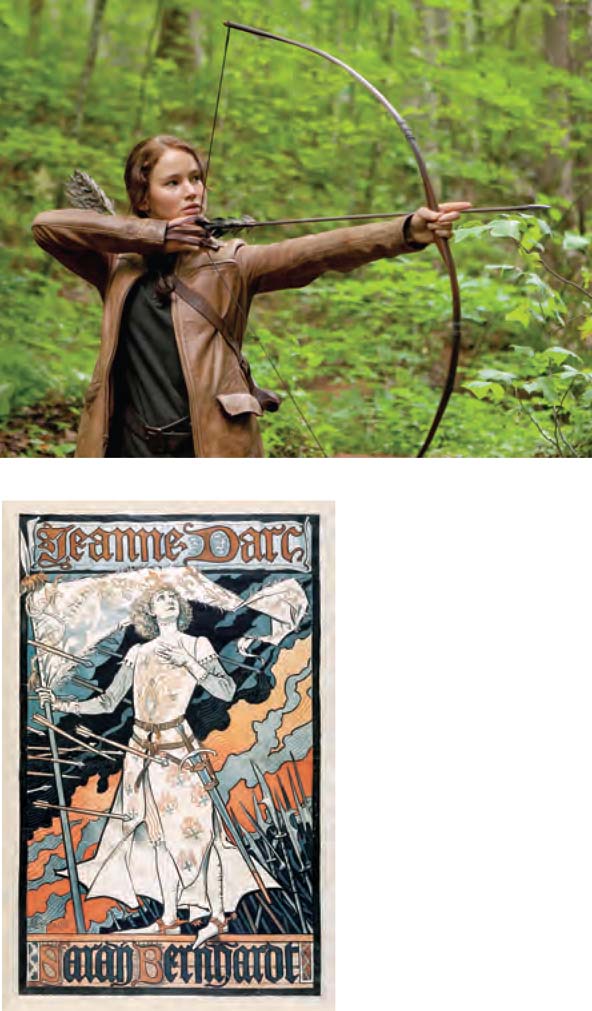

Jung also differed from Freud in his view of the unconscious. Jung believed personality is made up of the ego (at the conscious level), a personal unconscious, and a collective unconscious. The personal unconscious is akin to Freud’s notion of the preconscious and the unconscious mind; items from the personal unconscious range from easily retrievable memories to anxiety-provoking repressed memories. The collective unconscious, according to Jung, holds the universal experiences of humankind passed from generation to generation, memories that are not easily retrieved without some degree of effort or interpretation. We inherit a variety of primal images, patterns of thoughts, and storylines. The themes of these archetypes (är-ki-tīps) may be found in art, literature, music, dreams, and religions across time, geography, and culture. Some of the consistent archetypes include the nurturing mother, powerful father, innocent child, and brave hero. Archetypes provide a blueprint for us as we respond to situations, objects, and people in our environments (Jung, 1969). The anima refers to the part of our personality that is feminine, and the animus to that which is masculine. Jung believed both of these parts exist in everyone’s personality, and we must acknowledge and appreciate them. Failure to accept the anima and animus can result in an imbalance, which prevents us from being whole.

Karen Horney

Karen Horney ( ˌnī 1885–1952) was a neo-Freudian who emphasized the role of relationships between children and their caregivers, not erogenous zones and psychosexual stages. She believed individuals respond to feelings of helplessness and isolation created by inadequate parenting, which she referred to as basic anxiety (Horney, 1945). In order to deal with this anxiety, Horney suggested that people use three strategies: moving toward people (looking for affection and acceptance), moving away from people (looking for isolation and self-sufficiency), or moving against people (looking to control others). Horney believed that a balance of these three strategies is important for psychological stability. She was also a committed critic of Freud’s sexist approach to the female psyche, pointing out that women are not jealous of the penis itself, but rather what it represents in terms of power and status in society. Horney (1926/1967) also proposed that boys and men can envy women’s ability to bear and breastfeed children.

ˌnī 1885–1952) was a neo-Freudian who emphasized the role of relationships between children and their caregivers, not erogenous zones and psychosexual stages. She believed individuals respond to feelings of helplessness and isolation created by inadequate parenting, which she referred to as basic anxiety (Horney, 1945). In order to deal with this anxiety, Horney suggested that people use three strategies: moving toward people (looking for affection and acceptance), moving away from people (looking for isolation and self-sufficiency), or moving against people (looking to control others). Horney believed that a balance of these three strategies is important for psychological stability. She was also a committed critic of Freud’s sexist approach to the female psyche, pointing out that women are not jealous of the penis itself, but rather what it represents in terms of power and status in society. Horney (1926/1967) also proposed that boys and men can envy women’s ability to bear and breastfeed children.

Questioning Freud

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory was groundbreaking and controversial, and it led to a variety of extensions and permutations through neo-Freudians such as Adler, Jung, Horney, and Erikson. Freud’s theories are considered among the most important in the field of personality development. He courageously called attention to the existence of infant sexuality at a time when sex was a forbidden topic of conversation. He recognized the importance of infancy and early childhood in the unfolding of personality, and appreciated the universal stages of human development. It was a blow to our collective self-esteem to realize that so much of our thinking occurs without conscious awareness, but this notion has been widely accepted, even among psychologists who are not Freudians or neo-Freudians. Some suggest Freud’s work has “become so pervasive in Western thinking that he is to be ranked with Darwin and Marx for introducing new—and often disturbing—modes of thought in Western culture” (Hilgard, 1987, p. 99).

show what you know

Question 11.4

1. According to Freud, all children go through __________ stages as they mature into adulthood. If conflicts are not successfully resolved along the way, a child may suffer from a __________.

psychosexual; fixation

Question 11.5

2. Freud’s __________ includes three levels: conscious, preconscious, and unconscious.

- structural model of the mind

- developmental model

- individual psychology

- topographical model of the mind

d. topographical model of the mind

Question 11.6

3. Jung believed personality is made up of the ego, a personal unconscious, and the:

- id.

- collective unconscious.

- superego.

- preconscious.

b. collective unconscious.

Question 11.7

4. How did the theories of the neo-Freudians differ from Freud’s psychoanalytic theory in regard to personality development?

Answers will vary, but could include the following. Some of Freud’s followers branched out on their own due to disagreements about certain issues, such as his focus on the instincts of sex and aggression, his idea that personality is determined by the end of childhood, and his somewhat negative view of human nature. Adler proposed that humans are conscious and intentional in their behaviors. Jung suggested that we are driven by a psychological energy (as opposed to sexual energy), which encourages positive growth, self-understanding, and balance. Horney emphasized the role of relationships between children and their caregivers, not erogenous zones and psychosexual stages.