11.5 Trait Theories and Their Biological Basis

A FEW WORDS ABOUT TANK

If you ask Dr. Reid Simmons to come up with some adjectives to describe Tank the Roboceptionist, he will offer words like “conscientious,” “agreeable,” “reserved,” “naïve,” “loyal,” and “caring.” All of these are examples of traits, the relatively stable properties of personality. The trait theories presented in this next section are different from theories discussed earlier in that they focus less on explaining why and how personality develops and more on describing personality and predicting behaviors.

If you ask Dr. Reid Simmons to come up with some adjectives to describe Tank the Roboceptionist, he will offer words like “conscientious,” “agreeable,” “reserved,” “naïve,” “loyal,” and “caring.” All of these are examples of traits, the relatively stable properties of personality. The trait theories presented in this next section are different from theories discussed earlier in that they focus less on explaining why and how personality develops and more on describing personality and predicting behaviors.

Who’s Who in Trait Theory

Allport and Personality

LO 11 Distinguish trait theories from other personality theories.

One of the first trait theorists was Gordon Allport (1897–1967), who created a comprehensive list of traits to describe personality. One primary reason for developing this list was to operationalize the terminology used in personality research; when researchers study the same topic, they should agree on definitions. If two researchers are studying a trait called “vivacious,” they will have an easier time comparing results if they use the same definition. Allport and his colleague carefully reviewed Webster’s New International Dictionary (1925) and identified 17,953 words (out of approximately 400,000 entries in the dictionary) that they proposed were “descriptive of personality or personal behavior” (Allport & Odbert, 1936, p. 24). The list contained terms that were considered to be personal traits (such as “acrobatical” and “zealous”), temporary states (such as “woozy” and “thrilled”), social evaluations (such as “swine” and “outlandish”), and metaphorical and doubtful (such as “mortal” and “middle-aged”). Most relevant to personality were the personal traits, of which they identified 4,504—a little over 1% of all the entries in the dictionary. Surely, this long list could be condensed, reduced, or classified to make it more manageable. Enter Raymond Cattell.

Cattell and Personality

Raymond Cattell (1905–1998) proposed grouping the long list of personality traits into two major categories: surface traits and source traits (Cattell, 1950). Surface traits are the easily observable personality characteristics we commonly use to describe people: She is quiet. He is friendly. Source traits are the foundational qualities that give rise to surface traits. For example, “extraversion” is a source trait, and the surface traits it produces may include “warm,” “gregarious,” and “assertive.” There are thousands of surface traits but only a few source traits. Cattell (1950) proposed that source traits are the product of both heredity and environment (nature and nurture), and surface traits are the “combined action of several source traits”.

Cattell also condensed the list of surface traits into a much smaller set of 171. Realizing that some of these surface traits would be correlated, he used a statistical procedure known as factor analysis to group them into a smaller set of dimensions according to common underlying properties. With factor analysis, Cattell was able to produce a list of 16 personality factors.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described a correlation as a relationship between two variables. Here, we describe factor analysis, which examines the relationships among an entire set of variables.

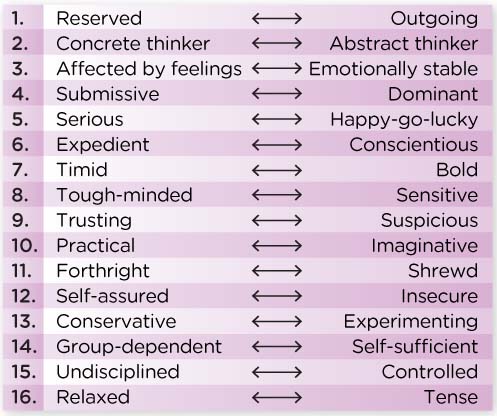

These 16 factors, or personality dimensions, can be considered primary source traits. Looking at Figure 11.2, you can see that the ends of the dimensions represent polar extremes. On one end of the first dimension is the reserved and unsocial person; at the other end is the “social butterfly.” Based on these factors, Cattell developed the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF), which is described in greater detail later in the chapter, in the section on objective personality tests.

Eysenck and Personality

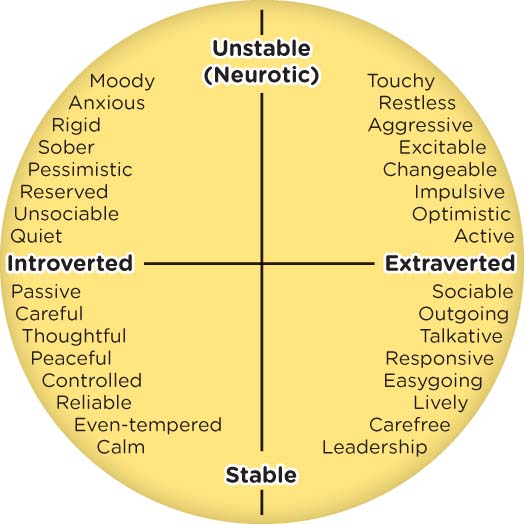

Hans Eysenck (1916–1997) continued to develop our understanding of source traits, proposing that we could describe personalities using three dimensions: introversion–extraversion (E), neuroticism (N), and psychoticism (P) (FIGURE 11.3).

People high on the extraversion end of the introversion–extraversion (E) dimension tend to display a marked degree of sociability and are outgoing and active with others in their environment. Those on the introversion end of the dimension tend to be quiet and careful and enjoy time alone. Having high neuroticism (N) typically goes hand in hand with being restless, moody, and excitable, while low neuroticism means being calm, reliable, and emotionally stable. A person who is high on the psychoticism dimension is likely to be cold, impersonal, and antisocial, whereas someone at the opposite end of this dimension is warm, caring, and empathetic. (The psychoticism dimension is not related to psychosis, which is described in Chapter 13.)

In addition to identifying these dimensions, Eysenck worked diligently to unearth their biological basis. For example, Eysenck (1967) proposed a direct relationship between the behaviors associated with the introversion–extraversion dimension and the reticular formation. According to Eysenck (1967, 1990), introverted people display higher reactivity in their reticular formation than those who are extraverted. An introvert has higher levels of arousal, thus is more likely to react to stimuli, and therefore has developed a pattern of behavior to cope. He may be more careful or restrained, for example. An extravert has lower levels of arousal, and thus is less reactive to stimuli. Extraverts seek stimulation because their arousal levels are low, so they tend to be more impulsive and outgoing.

The trait theories of Allport, Cattell, and Eysenck paved the way for the trait theories commonly used today. Let’s take a look at one of the most popular models.

The Big Five

LO 12 Identify the biological roots of the five-factor model of personality.

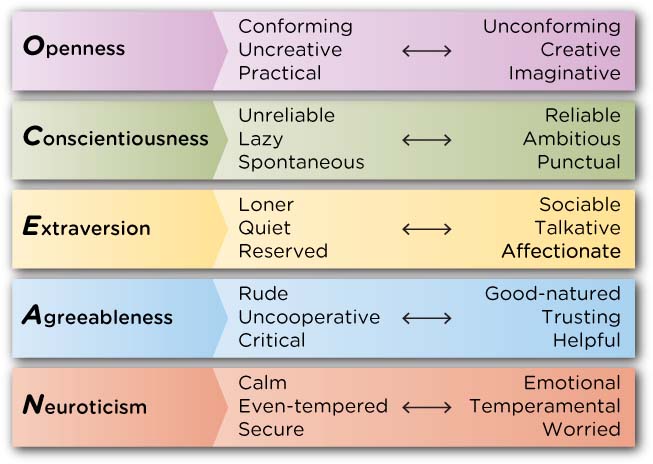

The five-factor model of personality, also known as the Big Five, is a current trait approach for explaining personality (McCrae & Costa, 1987). This model, developed using factor analysis, indicates there are five factors, or dimensions, to describe personality. Although 100% agreement does not exist on the names of these factors, in general, trait theorists propose they are openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (McCrae, Scally, Terracciano, Abecasis, & Costa, 2010). Openness is the degree to which someone is willing to try new experiences. Conscientiousness refers to someone’s attention to detail and organizational tendencies. The extraversion and neuroticism dimensions are similar to Eysenck’s dimensions noted earlier: Extraversion refers to degree of sociability and outgoingness; neuroticism, to emotional stability (degree to which a person is calm, secure, and even tempered). Agreeableness indicates how trusting and easygoing a person is. To remember these factors, students sometimes use the mnemonic OCEAN: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (FIGURE 11.4).

Empirical support for this model has been established using cross-cultural testing. People in more than 50 cultures, who speak languages as diverse as German, Spanish, and Czech, have been shown to exhibit these five dimensions (McCrae et al., 2000, 2005, 2010). Even the everyday terms used to describe personality characteristics across continents (North America, Europe, and Asia) fit well with the five-factor model (McCrae et al., 2010).

One possible explanation is that these five dimensions are biologically based and universal to humans (Allik & McCrae, 2004; McCrae et al., 2000). Three decades of twin and adoption studies point to a genetic basis of these five factors (McCrae et al., 2000; Yamagata et al., 2006), with openness to experience showing the greatest degree of heritability (McCrae et al., 2000; TABLE 11.4). Some researchers suggest that dog personalities also can be described using similar dimensions, such as extraversion and neuroticism (Ley, Bennett, & Coleman, 2008). And such research is not limited to canines; animals as diverse as squid and orangutans seem to display personality characteristics that are surprisingly similar to those observed in humans (Sinn & Moltschaniwskyj, 2005; Weiss, King, & Perkins, 2006).

| Big Five Personality Dimensions | Heritability |

|---|---|

| Openness | .61 |

| Conscientiousness | .44 |

| Extraversion | .53 |

| Neuroticism | .41 |

| Agreeableness | .41 |

| Heritability is the degree to which heredity is responsible for a particular characteristic. Here, we can see the percent of variation in the Big Five traits attributed to genetic make-up, leaving the remainder to be attributed to environmental influences. | |

| SOURCE: JANG, LIVESLEY, AND VERNON (1996). | |

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we described the Minnesota twin studies, which showed that genes play a role in intellectual abilities. Identical twins share 100% of their genes, fraternal twins share about 50% of their genes, and adopted siblings are genetically very different. Comparing personality traits among these siblings can show the relative importance of genes (nature) and the environment (nurture).

More evidence for the biological basis of these five factors is apparent from their general stability over time (Kandler et al., 2010; McCrae et al., 2000). This implies that the dramatic environmental changes most of us experience in life do not have as great an impact as our inherited characteristics. That does not mean personalities are completely static, however; people can experience changes in these five factors over the life span (Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2011). For example, as people age, they tend to score higher on agreeableness and lower on neuroticism, openness, extraversion, and conscientiousness. They also seem to become happier and more easygoing with age, displaying more positive attitudes (Marsh, Nagengast, & Morin, 2013). Yet, a study of forager-farmers in Bolivia indicated that this model of personality was not a good fit for a predominantly illiterate and indigenous “small-scale society” (Gurven, von Rueden, Massenkoff, Kaplan, & Lero Vie, 2013).

Men and women appear to differ with respect to the five factors, although there is not total agreement on how. Schmitt and colleagues reviewed studies from 55 nations and reported that, across cultures, women score higher than men on conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (Schmitt, Realo, Voracek, & Allik, 2008). Men, on the other hand, seem to demonstrate greater degrees of openness to experience. These disparities are not extreme, however; the variation within the groups of males and females is greater than the differences between males and females. Critics suggest that using such rough measures of personality may conceal some of the true differences between men and women; in order to shed light on such disparities, they suggest investigating models that incorporate 10 to 20 traits rather than just 5 (Del Guidice, Booth, & Irwing, 2012).

Maybe you could have predicted women would score higher on measures of agreeableness and neuroticism; perhaps you would have guessed the opposite. Research suggests that some gender stereotypes do indeed contain a kernel of truth (Costa, Terracciano, & McCrae 2001; Terracciano et al., 2005). Let’s find out if this principle holds true for cultural stereotypes as well.

across the WORLD

Culture of Personality

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 10, we presented the gender similarities hypothesis, which states that, overall, the variation within a gender is greater than the variation between genders. Here we see how this applies to the five factors of personality.

Have you heard the old joke about European stereotypes? It goes something like this: In heaven, the chefs are French, the mechanics German, the lovers Italian, the police officers British, and the bankers Swiss (Mulvey, 2006, May 15). This joke plays upon what psychologists might call “national stereotypes,” or preconceived notions about the personalities of people belonging to certain cultures. The joke assumes, for example, that Italian people have some underlying quality that makes them excel in romance but not money management. Are such national stereotypes accurate?

Have you heard the old joke about European stereotypes? It goes something like this: In heaven, the chefs are French, the mechanics German, the lovers Italian, the police officers British, and the bankers Swiss (Mulvey, 2006, May 15). This joke plays upon what psychologists might call “national stereotypes,” or preconceived notions about the personalities of people belonging to certain cultures. The joke assumes, for example, that Italian people have some underlying quality that makes them excel in romance but not money management. Are such national stereotypes accurate?

PLEASE LEAVE YOUR STEREOTYPES AT THE BORDER!

To get to the bottom of this question, Terracciano and colleagues (2005) used personality tests to assess the Big Five traits of nearly 4,000 people from 49 cultures. When they compared the results of the personality tests to national stereotypes, they found no evidence that the stereotypes mirrored reality. Not only are these stereotypes invalid, but as history demonstrates, they can pave the way for “prejudice, discrimination, or persecution”.

Taking Stock: An Appraisal of the Trait Theories

As you can see from the examples above, trait theories have facilitated important psychological research. But like any scientific approach, they have their flaws. One major criticism is that trait theories fail to explain the origins of personality. What aspects of personality are innate, and which are environmental? How do unconscious processes, motivations, and development influence personality? If you’re looking to answer these types of questions, trait theories might not be your best bet.

Trait theories also tend to underestimate environmental influences on personality. As Walter Mischel pointed out, environmental circumstances can affect the way traits manifest themselves (Mischel & Shoda, 1995). A person who is high on the openness factor may be nonconforming in college, wearing unique clothing and pursuing unusual hobbies, but put her in the military and her nonconformity will probably assume a new form.

We are about to wrap up our discussion of the trait theories and move on to the intriguing topic of personality testing. Before we do so, though, let’s look at one final example illustrating the value of trait theories. Which of the Big Five would you guess is linked to longevity?

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Open Mind, Longer Life

The trait of openness improves health through creativity

Researchers have long been studying the connection between health and the five major personality traits: agreeableness, extraversion, neuroticism, openness and conscientiousness. A large body of research links neuroticism with poorer health and conscientiousness with superior health. Now openness, which measures cognitive flexibility and the willingness to entertain novel ideas, has emerged as a lifelong protective factor. The linchpin seems to be the creativity associated with the personality trait—creative thinking reduces stress and keeps the brain healthy.

A study published in the June issue of the Journal of Aging and Health found that higher openness predicted longer life, and other studies this year have linked that trait with lower metabolic risk, higher self-rated health, and more appropriate stress response.

The June study sought to determine whether specific aspects of openness better predicted survival rates than overall openness, using data on more than 1,000 older men collected between 1990 and 2008. The researchers found that only creativity—not intelligence or overall openness—decreased mortality risk. One possible reason creativity is protective of health is because it draws on a variety of neural networks within the brain, says study author Nicholas Turiano, now at the University of Rochester Medical Center. “Individuals high in creativity maintain the integrity of their neural networks even into old age,” Turiano says—a notion supported by a January study from Yale University that correlated openness with the robustness of study subjects’ white matter, which supports connections between neurons in different parts of the brain.

Because the brain is the command center for all bodily functions, exercising it helps all systems to continue running smoothly. “Keeping the brain healthy may be one of the most important aspects of aging successfully—a fact shown by creative persons living longer in our study,” Turiano says.

He also cites creative people’s ability to handle stress—they tend not to get as easily flustered when faced with an emotional or physical hurdle. Stress is known to harm overall health, including cardiovascular, immune and cognitive systems. “Creative people may see stressors more as challenges that they can work to overcome rather than as stressful obstacles they can’t overcome,” Turiano says. Although studies thus far have looked at those who are naturally open-minded, the results suggest that practicing creative-thinking techniques could improve anyone’s health by lowering stress and exercising the brain. Tori Rodriguez. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2012 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

show what you know

Question 11.14

1. The relatively stable properties that describe elements of personality are:

- traits.

- expectancies.

- reinforcement values.

- ego defense mechanisms.

a. traits.

Question 11.15

2. The traits we easily observe and quickly describe based on someone’s behavior or characteristics are called __________.

surface traits

Question 11.16

3. Name the Big Five traits and give one piece of evidence for their biological basis.

Answers will vary (and see Table 11.4). The Big Five traits include openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Three decades of twin and adoption studies point to a genetic (and therefore biological) basis of these five factors. The proportion of variation in the Big Five traits attributed to genetic make-up is substantial (ranging from .41 to .61), suggesting that the remainder can be attributed to environmental influences.