12.4 Factors related to Stress

First responders encounter a wide variety of scenarios, ranging in intensity from five-car pile-ups to soccer injuries. What determines how a first responder reacts in these situations? There are two types of variables to consider: those that reside within the individual and those that exist in the environment. We can see both of these variables at work in one of the most common stressors of everyday life: conflict.

Conflicts

LO 9 Identify different types of conflicts.

When most people think of conflict, they imagine fist fights and arguments, but here conflict is defined as the discomfort one feels when making tough choices. There are various types of conflict. In an approach–approach conflict, two or more favorable alternatives are pitted against each other. Here, you must choose between two options you find attractive. Imagine this situation: You have to pick only one class this semester, and to fit your schedule, you must choose between two classes you would really like to take. An approach-avoidance conflict occurs when you face a choice or situation that has both favorable and unfavorable characteristics. You are required to take a biology lab class this semester, and although you like biology, you do not like working with other students in lab settings. You are faced with an approach–avoidance conflict (you enjoy biology/you don’t like working with partners). A third type of conflict is the avoidance–avoidance conflict, which occurs when you are faced with two or more alternatives that are unattractive. In order to fulfill a requirement, you must choose between two courses that you really dread taking.

Let’s test your understanding of these conflict types, using some examples related to police work:

- Imagine you are a police officer contemplating whether to arrest a mother and father suspected of child abuse. If you make the arrest, all of the children in the home will be placed in foster care, an unfamiliar, often frightening environment for children. Something good will come out of the change (the children are no longer at risk of being abused), but the downside is that the children will be thrown into an unfamiliar environment. Approach–avoidance. There is an upside and a downside to removing the children from their home.

- You are new to the police force. It is your second day on the job, and you are given a choice between the following two tasks: ride in the squad car with a partner you dislike or stay in the station all day and answer calls (a very boring choice). You are torn, because you really don’t want to do either of these things. Avoidance–avoidance. Both decisions lead to negative outcomes––a hard day for you.

- You are a 30-year veteran of the Houston police department. You can either retire now and begin receiving a pension or stay on the job and continue to enjoy your work. Approach–approach. Both options are positive—retiring early or continuing to work.

Conflicts can be even more complicated than this. A double approach–avoidance conflict occurs when you must decide between two choices, each possessing attractive and unattractive qualities. For example, a student trying to decide whether to purchase an e-book or a hardback might create a list of the good and bad qualities for both types of books. On the one hand, the e-book allows for portability and quick access, but it is not a good option if the Internet fails or electricity is unavailable. The hardback is long lasting and always accessible, but it is heavy and more expensive. You might even have to deal with multiple approach–avoidance conflicts, which occur when you are faced with a decision that has more than two possible choices. You are trying to decide where to live when you attend college in a new city. Should you apply for a dormitory room, look for an apartment, share a house, or live with a family member? Each of these choices has attractive and unattractive qualities.

Sometimes conflicts and other stressors pile up so high they become difficult to tolerate. When we can no longer deal with stress in a constructive way, we experience what psychologists call burnout.

AMBULANCE BURNOUT

Kehlen has been in the EMS field for nearly a decade, and most of that time he has spent working for a private ambulance company. He estimates that the average ambulance worker lasts about 8 years before quitting to pursue another line of work. What makes this career so hard to endure? The pay is dismal, the 24-hour shifts grueling, and the constant exposure to trauma profoundly disturbing. The pressure to perform is enormous, but there is seldom a “thank-you” or recognition for a job well done. Perhaps no other profession involves so much responsibility—combined with so little appreciation. “The ambulance crews, they’re kind of like the silent heroes,” Kehlen explains. “You work so hard and you don’t get any thanks at the end of the day.”

Kehlen has been in the EMS field for nearly a decade, and most of that time he has spent working for a private ambulance company. He estimates that the average ambulance worker lasts about 8 years before quitting to pursue another line of work. What makes this career so hard to endure? The pay is dismal, the 24-hour shifts grueling, and the constant exposure to trauma profoundly disturbing. The pressure to perform is enormous, but there is seldom a “thank-you” or recognition for a job well done. Perhaps no other profession involves so much responsibility—combined with so little appreciation. “The ambulance crews, they’re kind of like the silent heroes,” Kehlen explains. “You work so hard and you don’t get any thanks at the end of the day.”

It might not surprise you that the EMS profession has one of the highest rates of burnout (Gayton & Lovell, 2012). Burnout refers to emotional, mental, and physical fatigue that results from repeated exposure to challenges, leading to reduced motivation, enthusiasm, and performance. People who work in the helping professions, such as nurses, mental health professionals, and child protection workers, are clearly at risk for burnout (Jenaro, Flores, & Arias, 2007; Linnerooth, Mrdjenovich, & Moore, 2011; Rupert, Stevanovic, & Hunley, 2009).

I Can Deal: Coping with Stress

Police work is among the most stressful careers around, and it is not for everybody. To survive and thrive in this career, you must excel under pressure. Police departments need officers who are emotionally stable and capable of making split-second decisions with potentially serious ethical implications. If a tired, stressed-out officer makes one bad decision, the reputation of the entire police department could be tarnished. No wonder over 90% of city police departments in the United States require job applicants to take psychological evaluations, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2 (MMPI–2) (Butcher & Rouse, 1996; Cochrane, Tett, & Vandecreek, 2003). Psychological testing is just one hurdle facing the aspiring police officer; some departments also require full-length meetings with a psychologist. And most city agencies also require criminal background checks, polygraph (lie detector) tests, and physical fitness assessments. And don’t forget the 1,000-or-so hours of training at the police academy (Cochrane et al., 2003). But even after overcoming all the hurdles of the hiring process, some police officers end up struggling with stress management. In this respect, police work is like any other field; there will always be people who have trouble coping with the stress of the job.

Eric: Has the stress of police training ever made you want to quit?

Appraisal and Coping

LO 10 Illustrate how appraisal influences coping.

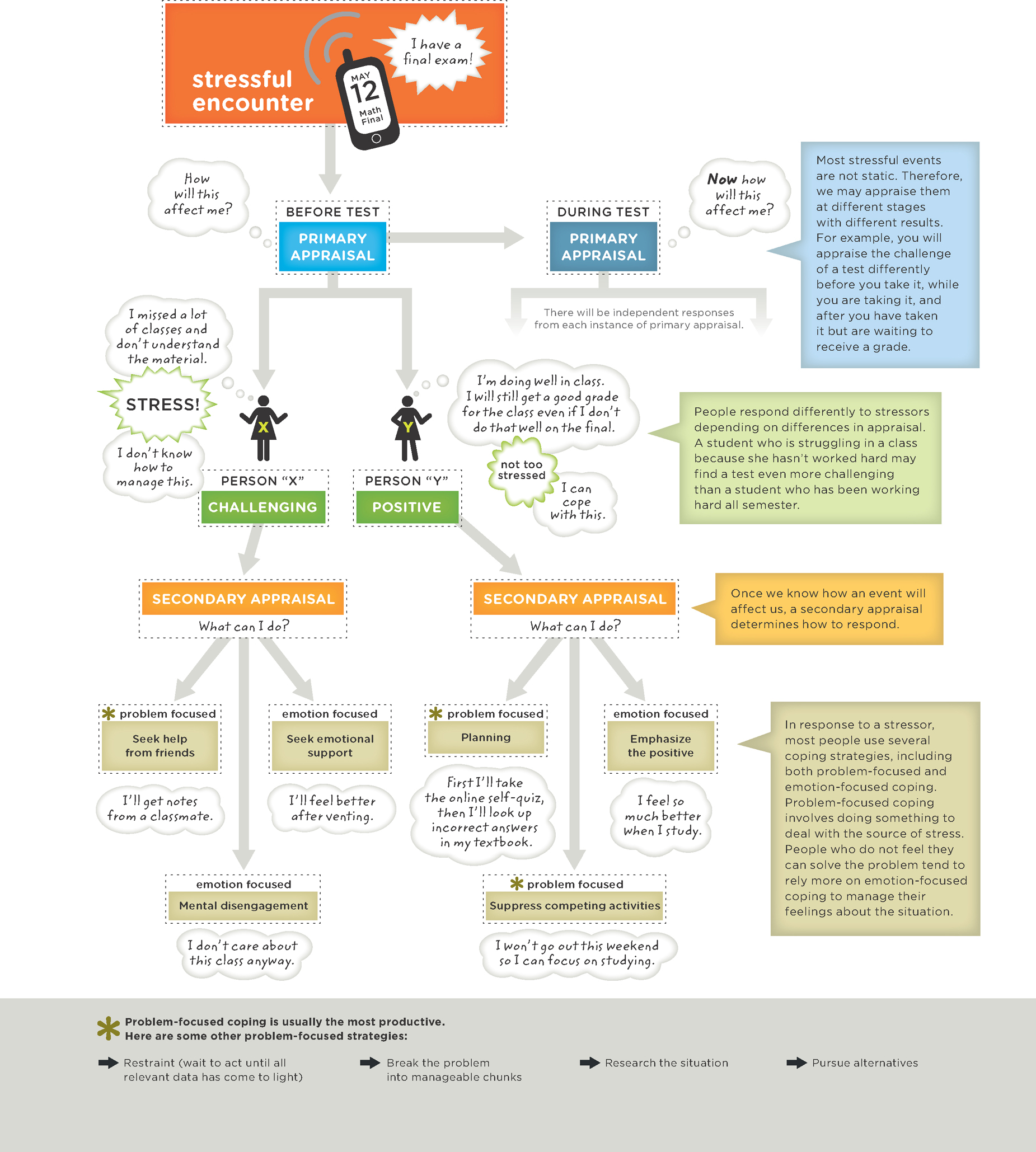

Needless to say, people respond to stress in their own unique ways. Lazarus suggests that stress is the result of a person’s appraisal of a stressor, not necessarily the stressor itself (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). This viewpoint stands in contrast to Selye’s suggestion (noted earlier) that we all react to stressors in a similar manner. Coping refers to the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional abilities used to effectively manage something that is perceived as difficult or challenging. In order to cope, we must determine if an event is harmful, threatening, or challenging (Infographic 12.2). A person making a primary appraisal of a situation determines how the event will affect him. He must decide if it is irrelevant, positive, challenging, or harmful. Determining whether something constitutes a threat, for example, is a personal appraisal. Next, the individual makes a secondary appraisal, or decides how to respond. If he believes he can cope with virtually any challenge that comes his way, the impact of stress remains low. If he thinks his coping abilities are poor, then the impact of stress will be high. These differences in appraisals help explain why two people can react to the same event in dramatically different ways.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we described the cognitive-appraisal theory of emotion, which suggests that emotion results from the way people appraise or interpret interactions they have. We appraise events based on their significance, and our subjective appraisal influences our response to stressors.

There are two basic types of coping. Problem-focused coping means taking a direct approach, confronting a problem head-on. Suppose you are having troubles in a relationship; an example of problem-focused coping might be reading self-help books or finding a counselor. Emotion-focused coping involves addressing the emotions that surround a problem, rather than trying to solve it. With a troubled relationship, you might think about your feelings and how miserable you are, instead of addressing the problem directly. Sometimes it’s better to use emotion-focused coping—when an emotional reaction might be too stressful or interferes with daily functioning, or when a problem cannot be solved (for example, the death of a loved one). In the long run, however, problem-focused coping is usually more productive.

Eric: Do you ever feel so overwhelmed that you can’t relax?

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

In June 2011 Eric began his second run through Onondaga’s police training program. This time around, he nailed the Emergency Vehicle Operations Course (EVOC). “I can’t even describe to you how great it felt.” The secret to his success? “Instead of worrying about everything, I had fun,” Eric says. “Once you relax…[it] helps you focus better.” Eric graduated in December 2011. He soon landed a position with a local police department.

In June 2011 Eric began his second run through Onondaga’s police training program. This time around, he nailed the Emergency Vehicle Operations Course (EVOC). “I can’t even describe to you how great it felt.” The secret to his success? “Instead of worrying about everything, I had fun,” Eric says. “Once you relax…[it] helps you focus better.” Eric graduated in December 2011. He soon landed a position with a local police department.

“Police training is different everywhere,” says Eric, who chose the police academy at Onondaga Community College because of its rigor. No training program can totally prepare you for police work, but the academy makes every effort to simulate real-world scenarios. “The individuals who can deal with stress in the best way make it through,” says Eric. “Those that cannot weed themselves out on their own.”

Type A and Type B Personalities

LO 11 Describe Type A and Type B personalities and explain how they relate to stress.

Personality appears to have a profound effect on coping style and predispositions to stress-related illness. For example, people with certain personality types are more prone to developing cardiovascular disease. How do we know this? Two cardiologists, Meyer Friedman and Ray Rosenman, were among the first to suspect a link between personality type and the cardiovascular problems they observed in their patients (Friedman & Rosenman, 1974). Specifically, they noted that many of the people they treated were intensely focused on time and always in a hurry. This characteristic pattern of behaviors eventually was referred to as Type A personality. Someone with a Type A personality is competitive, aggressive, impatient, and often hostile (Diamond, 1982; Smith & Ruiz, 2002). Through numerous studies, Friedman and Rosenman discovered that people with Type A personalities were twice as likely to develop cardiovascular disease as those with Type B personality. People with Type B personality are found to be more relaxed, patient, and nonaggressive (Rosenman et al., 1975). There appear to be various reasons people with Type A personality suffer disproportionately from cardiovascular disease: they are more likely to have high blood pressure, heart rate, and stress hormone levels. Type A individuals are also prone to more interpersonal problems (for example, arguments, fights, or hostile interactions), which increase the time their bodies are prepared for fight or flight.

INFOGRAPHIC 12.2: The Process of Coping

Coping refers to the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral methods we employ to manage stressful events. But we don’t always rely on the same strategies to manage stressors in our lives. Coping is an individual process through which we appraise a stressor to determine how it will affect us and how we can respond.

Although many years of research confirmed the relationship between Type A behavior and coronary heart problems, some researchers began to report findings inconsistent with this (Smith & MacKenzie, 2006). Failure to reproduce the results led some to question the validity of this relationship, although one major factor was a lack of consistency in research methodology. For example, some studies used samples with high-risk participants, whereas others included healthy people. As researchers continued to probe the relationship between personality type and coronary heart disease, they found that the component of hostility in Type A personality was the strongest predictor of coronary heart disease.

Type D Personality

More recently, researchers have suggested another personality type that may better predict how patients fare when they already have heart disease: Type D personality, where the “D” refers to distress (Denollet & Conraads, 2011). Someone with Type D personality is characterized by emotions like worry, tension, bad moods, and social inhibition (avoids confronting others, poor social skills). There is a clear link between Type D characteristics and a “poor prognosis” in patients with coronary heart disease (Denollet & Conraads, 2011). In other words, people who have heart problems and exhibit these Type D characteristics are more likely to struggle with their illness. It could be that people with Type D personality tend to avoid dealing with their problems directly and don’t take advantage of social support. Such an approach might lead to poor choices about coping with stressors over time (Martin et al., 2011).

The Three Cs of Hardiness

Clearly, not everyone has the same tolerance for stress (Ganzel, Morris, & Wethington, 2010; Straub, 2012). Some people seem capable of handling intensely stressful situations (for example, war and poverty). These individuals appear to have a personality characteristic referred to as hardiness, meaning that even when functioning under a great deal of stress, they are very resilient and tend to remain positive. Kehlen, who considers himself “a very optimistic person,” may very well fit into this category, and findings from one study of Scottish ambulance personnel suggest that EMS workers with this characteristic are less likely to experience burnout (Alexander & Klein, 2001).

Kobasa (1979) and others have studied how some executives seem to withstand the effects of extremely stressful jobs. Their hardiness seems to be associated with three characteristics: feeling a strong commitment to work and personal matters; believing they are in control of the events in their lives and not victims of circumstances; and not feeling threatened by challenges, but rather seeing them as opportunities for growth. For example, Sheard (2009) reported that the level of commitment of nontraditional female students predicted higher academic success. Women who were older than 20 experienced a greater degree of success in their college work than their younger counterparts, presumably due to their commitment to obtaining an education.

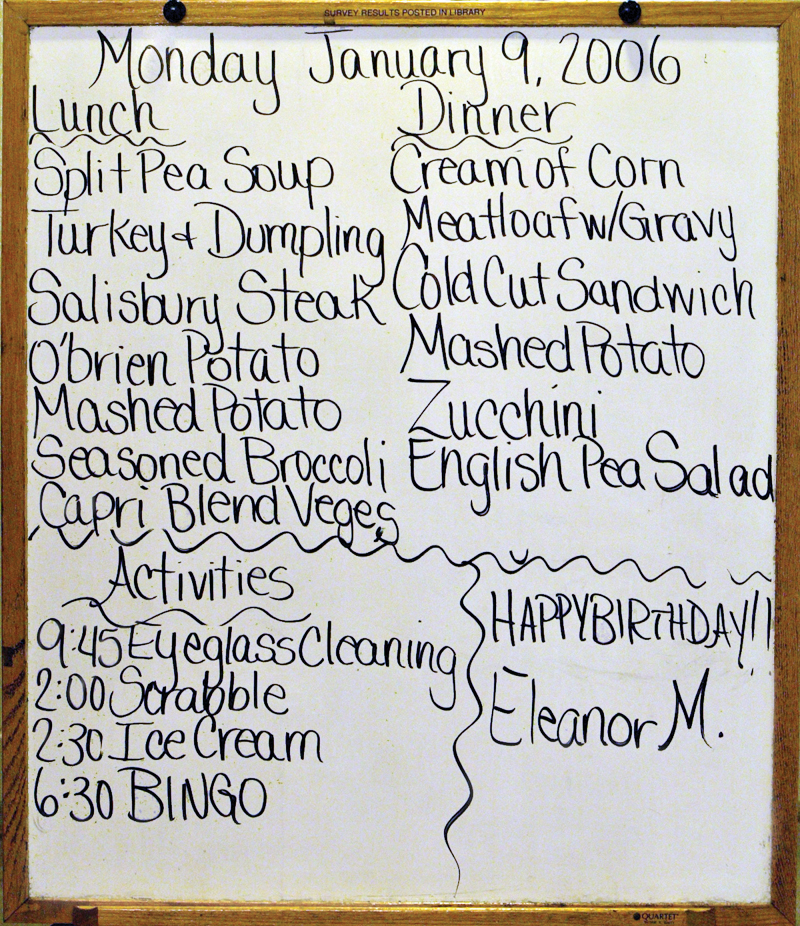

I Am in Control

The ability to respond to stress is very much dependent on one’s perceived level of personal control. Psychologists have consistently found that people who believe they have control over their lives, circumstances, and/or situations are less likely to experience the negative impact of stressors than those who do not feel the same control. For example, Langer and Rodin (1976) conducted a series of studies using nursing home residents as their participants. Residents in a “responsibility-induced” group were allowed to make a variety of choices about their daily activities as well as their environments. Members of the “comparison” group were not given these kinds of choices; instead, the nursing home staff made all of these decisions for them (the residents were told the staff were responsible for their happiness and care). After following the residents for 18 months, the researchers found that members of the responsibility-induced group were more lively, active in their social lives, and healthier than the residents in the comparison group. And twice as many of the residents in the comparison group died during this period (Rodin & Langer, 1977).

Researchers have examined how having a sense of personal control relates to a variety of health issues across all ages. Feelings of control are linked to how patients fare with some diseases. Cancer patients who exhibit a “helpless attitude” regarding their disease seem more likely to experience a recurrence of the cancer than those with perceptions of greater control. Why would this be? Women who have had breast cancer and believe they maintain control over their lifestyle, through diet and exercise, are more likely to make proactive changes related to their health, and perhaps reduce risk factors associated with recurrence (Costanzo, Lutgendorf, & Roeder, 2011). The same type of relationship is apparent in cardiovascular disease; the less control people feel they have, the greater their risk (Shapiro, Schwartz, & Astin, 1996). As we pointed out, having choices increases a perceived sense of control.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we discussed locus of control, a key component of personality. Someone with an internal locus of control believes the causes of outcomes reside within him. A person with an external locus of control thinks causes for outcomes reside outside of him. Here, we see that higher personal control is associated with better health outcomes.

But feelings of control may also have a more direct effect on the body; for example, a sense of powerlessness is associated with increases in catecholamines and corticosteroids, both key players in a typical physiological response to stress. Some have suggested that a causal relationship exists between feelings of perceived control and immune system function; the greater the sense of control, the better the functioning of the immune system (Shapiro et al., 1996). But these are correlations, and the direction of causality should not be assumed. Could it be that better immune functioning, and thus better health, might increase a sense of control?

We must also consider cross-cultural differences. Individual control is emphasized and valued in individualist cultures like our own, but not necessarily in collectivistic cultures, where people look to “powerful others” and “chance factors” to explain events and guide decision making (Cheng, Cheung, Chio, & Chan, 2013).

Locus of Control

Differences in perceived sense of control stem from beliefs about where control resides (Rotter, 1966). Someone with an internal locus of control generally feels as if she is in control of life and its circumstances; she probably believes it is important to take charge and make changes when problems occur. A person with an external locus of control generally feels as if chance, luck, or fate is responsible for her circumstances; there is no need to try to change things or make them better. How does this relate to health and stress? Any decisions related to healthy choices can be influenced by locus of control. Imagine that a doctor tells a patient he needs to change his lifestyle and start exercising. If the patient has an internal locus of control, he will likely take charge and start walking to work or hitting the gym at night; he expects his actions will impact his health outcome. If the patient has an external locus of control, he is more apt to think his actions won’t make a difference because his health is controlled by chance. Thus, he might not even attempt lifestyle changes. In the 1970 British Cohort Study, researchers examined over 11,000 children at age 10, and then assessed their health at age 30. Participants with an internal locus of control, measured at 10 years of age, were less likely as adults to be overweight or obese, and they had lower levels of psychological problems. Women with an internal locus of control were less likely to suffer from hypertension. Furthermore, people with a more internal locus of control were less likely to be smokers and more likely to exercise regularly than those with a more external locus of control (Gale, Batty, & Deary, 2008).

FROM AMBULANCE TO FIREHOUSE

Kehlen’s original career goal was to become a firefighter, but jobs are extremely hard to come by in this field. Fresh out of high school, Kehlen joined an ambulance crew with the goal of moving on to the firehouse. Seven years later, he reached his destination. Kehlen is now a firefighter paramedic with the Pueblo Fire Department. His job description still includes performing CPR, inserting breathing tubes, and delivering lifesaving medical care. But now he can also be seen handling fire hoses and rushing into 800-degree buildings with 80 pounds of gear.

Kehlen’s original career goal was to become a firefighter, but jobs are extremely hard to come by in this field. Fresh out of high school, Kehlen joined an ambulance crew with the goal of moving on to the firehouse. Seven years later, he reached his destination. Kehlen is now a firefighter paramedic with the Pueblo Fire Department. His job description still includes performing CPR, inserting breathing tubes, and delivering lifesaving medical care. But now he can also be seen handling fire hoses and rushing into 800-degree buildings with 80 pounds of gear.

Compared to an ambulance, the firehouse is a far more conducive environment for managing stress. For starters, there is enormous social support. Fellow firefighters are a lot like family members. They eat together, go to sleep together, and wake to the same flashing lights and tones announcing the latest emergency. “The fire department is such a brotherhood,” Kehlen says. Spending a third of his life at the firehouse with his colleagues, Kehlen has come to know and trust them on a deep level. They discuss disturbing events they witness and help each other recover emotionally. “If you don’t talk about it,” says Kehlen, “it’s just going to wear on you.” Another major benefit of working at the firehouse is having the freedom to exercise, which Kehlen considers a major stress reliever. The firefighters are actually required to work out 1 hour per day during their shifts.

Ambulance work is quite another story. Kehlen and his coworkers were friends, but they didn’t share the tight bonds that Kehlen now can count on at the firehouse. And eating healthy and exercising were almost impossible. Ambulance workers don’t have the luxury of making a healthy meal in a kitchen. They often have no choice but to drive to the nearest fast-food restaurant and wipe the crumbs off their faces as they race to the next emergency. One of the worst aspects of the job was the lack of exercise. Says Kehlen, “That killed me when I was in the ambulance.”

Tools for Healthy Living

LO 12 Discuss several tools for reducing stress and maintaining health.

Dealing with stressors can be challenging, but you don’t have to grin and bear it. There are many simple ways to manage and reduce stress. One of your most powerful stress-fighting weapons is physical exercise.

Exercise

You are feeling the pressure. Exam time is here, and you haven’t cracked open a book because you’ve been so busy at work. The holidays are approaching, you haven’t purchased a single present, and the pile of unpaid bills on your desk is starting to build. With so much to do, you feel paralyzed. In these types of situations, the best solution may be to drop to the floor to do some push-ups, or run out the door and take a jog. When you come back, you feel a new sense of calm. I can handle this, you’ll think to yourself. One thing at a time.

How does exercise work its magic? Physiologically, we know exercise increases blood flow, activates the autonomic nervous system, and helps initiate the release of several hormones. These physiological reactions help the body defend itself from potential illnesses, especially those that are stress related. Exercise also spurs the release of the body’s natural painkilling and pleasure-inducing neurotransmitters, the endorphins (Salmon, 2001).

When it comes to choosing an exercise regimen, the tough part is finding an activity that is intense enough to reduce the impact of stress, but sufficiently enjoyable to keep you coming back for more. Research has suggested that only 30 minutes of daily exercise is needed to decrease the risk of heart disease, stroke, hypertension, certain types of cancer, and diabetes (Warburton, Charlesworth, Ivey, Nettlefold, & Bredin, 2010) and improve mood (Bryan, Hutchison, Seals, & Allen, 2007; Hansen, Stevens, & Coast, 2001). And exercise needn’t be a chore. Your daily 30 minutes could mean dancing to Just Dance 4 on the Wii, going for a bike ride, raking leaves on a beautiful fall day, or shoveling snow in a winter wonderland.

Relax

Exercise is all about getting the body moving, but relaxing the muscles can also relieve stress. “Just relax.” We have heard it said a thousand times, but do we really know how to begin? Edmund Jacobson (1938) introduced a technique known as progressive muscle relaxation, which has since been expanded upon. With this technique, you begin by tensing a muscle group (for example, your toes), for about 10 seconds, and then releasing as you focus on the tension leaving. Next you progress to another muscle group, such as the calves, and then the thighs, buttocks, stomach, shoulders, arms, neck, forehead, and so on. After several weeks of practice, you will begin to recognize where you hold tension in your muscles—at least this is the goal. Once you become aware of that tension, you can focus on relaxing those specific muscles without going through the entire process. Progressive muscle relaxation has been shown to diffuse anxiety in highly stressed college students. In one study, researchers found that just 20 minutes of progressive muscle relaxation had “significant short-term effects,” including decreases in anxiety, blood pressure, and heart rate (Dolbier & Rush, 2012). Participants also reported a feeling of increased control and energy. This relaxation response may also serve as an effective way to reduce pain (Benson, 2000; Dusek et al., 2008).

CONTROVERSIES

Meditate on This

An increasingly popular way to induce relaxation is meditation. If you’ve ever known an anxious person who began meditating regularly, you know that it can have a dramatic “chilling out” affect. A sense of serenity envelops people who take up meditation. But anecdotal evidence or folk wisdom is no substitute for scientific data. What does the research say?

An increasingly popular way to induce relaxation is meditation. If you’ve ever known an anxious person who began meditating regularly, you know that it can have a dramatic “chilling out” affect. A sense of serenity envelops people who take up meditation. But anecdotal evidence or folk wisdom is no substitute for scientific data. What does the research say?

Numerous studies point to a variety of meditation-related physical and mental health benefits, including increased immune system activity, enhanced empathy, and reduced levels of anxiety, neuroticism, and negative emotions (Davidson et al., 2003; Roemer, Orsillo, & Salters-Pedneault, 2008; Sedlmeier et al., 2012; Walsh, 2011). This all sounds great, but some scholars assert that many meditation studies are riddled with methodological flaws and lack the support of solid theoretical frameworks (Ireland, 2012; Sedlmeier et al., 2012).

In many cases, it’s unclear whether meditation or some other lifestyle factor such as regular exercise is causing the positive effects researchers have observed. It’s also important to recognize that the expectations of research participants can sway study results in a favorable direction. In other words, just thinking meditation is beneficial may affect the way people perceive and report its effects. Meditation may exert a placebo effect, leading its practitioners to believe that their efforts are paying off. If this is the case, then the beliefs (rather than the meditation) are producing the health benefits.

…JUST THINKING MEDITATION IS BENEFICIAL MAY AFFECT THE WAY PEOPLE PERCEIVE AND REPORT ITS EFFECTS.

That said, we should point out that long-term meditation has been shown to produce observable changes in the brain (Davidson & Lutz, 2008; Hölzel et al., 2011). There is little doubt that something important happens when a person meditates, and that something appears to be positive. Now let’s take a closer look at some of the research pointing to one of those positive outcomes.

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Meditate That Cold Away

Practicing meditation or exercising might make you sick less often

To blunt your next cold, try meditating or exercising now. A new study from the University of Wisconsin–Madison found that adults who practiced mindful meditation or moderately intense exercise for 8 weeks suffered less from seasonal ailments during the following winter than those who did not exercise or meditate.

The study appeared in the July issue of Annals of Family Medicine. Researchers recruited about 150 participants, 80 percent of them women and all older than 50, and randomly assigned them to three groups. One group was trained for eight weeks in mindful meditation; another did eight weeks of brisk walking or jogging under the supervision of trainers. The control group did neither. The researchers then monitored the respiratory health of the volunteers with biweekly telephone calls and laboratory visits from September through May—but they did not attempt to find out whether the subjects continued meditating or exercising after the initial eight-week training period.

Participants who had meditated missed 76 percent fewer days of work from September through May than did the control subjects. Those who had exercised missed 48 percent fewer days during this period. The severity of the colds also differed between the two groups. Those who had exercised or meditated suffered for an average of five days; colds of participants in the control group lasted eight. Lab tests confirmed that the self-reported length of colds correlated with the level of antibodies in the body, which is a biomarker for the presence of a virus.

“I think the big news is that mindfulness meditation training appears to have worked” in preventing or reducing the length of colds, says Bruce Barrett of the department of family medicine. He cautions, however, that the findings are preliminary. Harvey Black. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2012 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Many forms of meditation emphasize control and awareness of breathing. This may be one of the reasons people find meditation so relaxing. Taking slow, deep breaths is a fast and easy way to reduce the impact of stress.

try this

Look at a clock or watch. Now breathe in slowly for 5 seconds. Then exhale slowly for 5 seconds. Do this for 1 minute. With each breath, you begin to slow down and your body starts to relax. The key, however, is to breathe deeply. Draw your breath deep into the diaphragm and avoid shallow, rapid chest breathing.

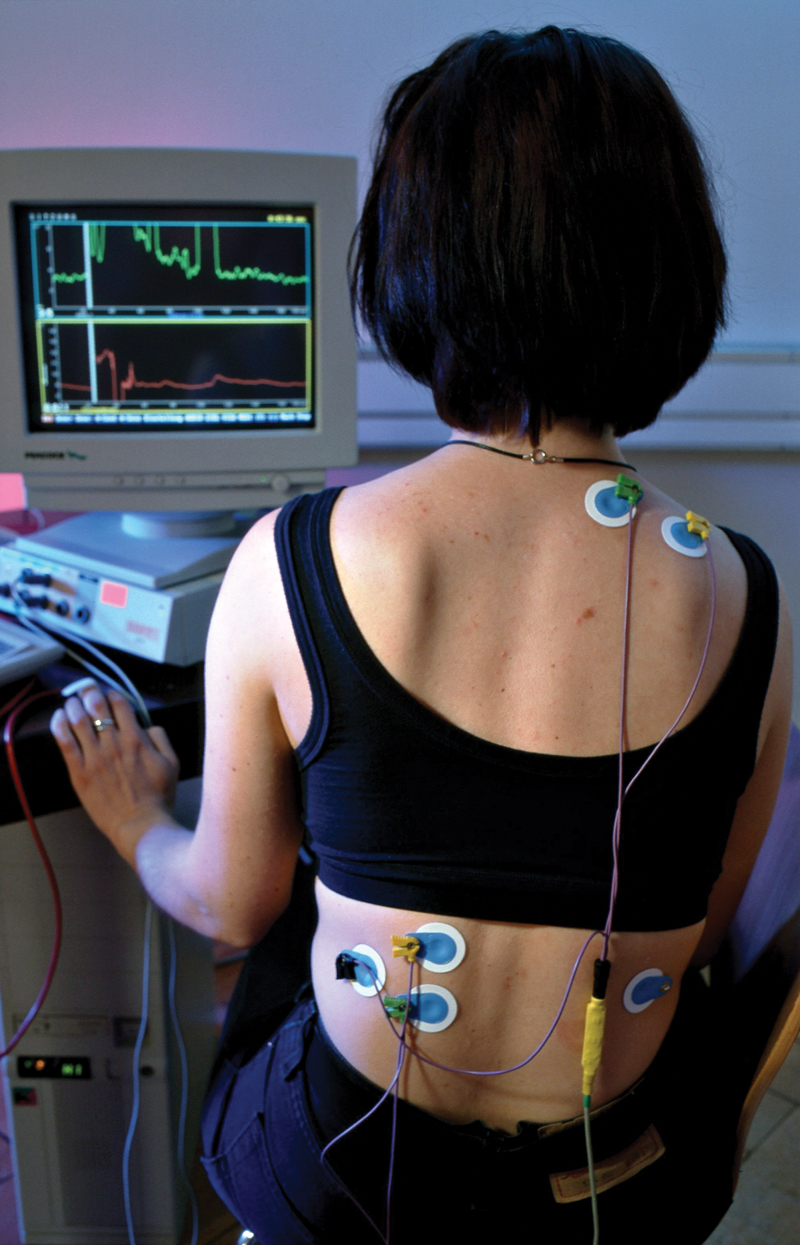

Biofeedback

A proven method for reducing physiological responses to stressors is biofeedback. This technique builds on learning principles and involves providing visual or auditory information about biological processes, allowing for control of seemingly involuntary physiological responses (such as heart rate, blood pressure, and skin temperature). The biofeedback equipment monitors internal responses and helps a person identify those that are maladaptive (for example, tense shoulder muscles). One would begin by focusing on a mechanism (a light or tone, for example) that indicates when a desired response occurs. By controlling the biofeedback indicator, one learns to maintain the desired response (relaxed shoulders in this example). The goal is to be able to tap into this technique outside of the clinic or lab, and translate what has been learned into real-life practice.

The use of biofeedback can decrease the frequency of headaches and chronic pain (Flor & Birbaumer, 1993; Sun-Edelstein & Mauskop, 2011). Biofeedback appears to be useful for all age groups, including children, adolescents, and the elderly (Morone & Greco, 2007; Palermo, Eccleston, Lewandowski, Williams, & Morley, 2010).

Social Support

Up until now, we have discussed ways to manage the body’s physiological response to stressors. There are also situational methods to deal with stressors, like maintaining a social support network. Researchers have found that proactively participating in positive enduring relationships with family, friends, and religious groups can generate a health benefit similar to exercise and not smoking (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). And people who maintain positive, supportive relationships also have better overall health (Walsh, 2011). Both Eric and Kehlen find family time to be a major stress reliever. At home with their wives and children, they feel relaxed and happy. Kehlen’s wife, a nurse practitioner, once worked in an emergency room, so she can relate to her husband’s experiences with trauma.

You might expect that receiving support is the key to lowering stress, but research suggests that giving support also really matters. In a study of older married adults, researchers reported reduced mortality rates for participants who indicated that they helped or supported others, including friends, spouses, relatives, and neighbors. There were no reductions in mortality, however, associated with receiving support from others (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003).

Helping others because it gives you pleasure, and expecting nothing in return, is known as altruism, and it appears to be an effective stress reducer and happiness booster (Schwartz, Keyl, Marcum, & Bode, 2009; Schwartz, Meisenhelder, Yunsheng, & Reed, 2003). When we care for others, we generally don’t have time to focus on our own problems; we also come to recognize that others may be dealing with more troubling circumstances or events than we are.

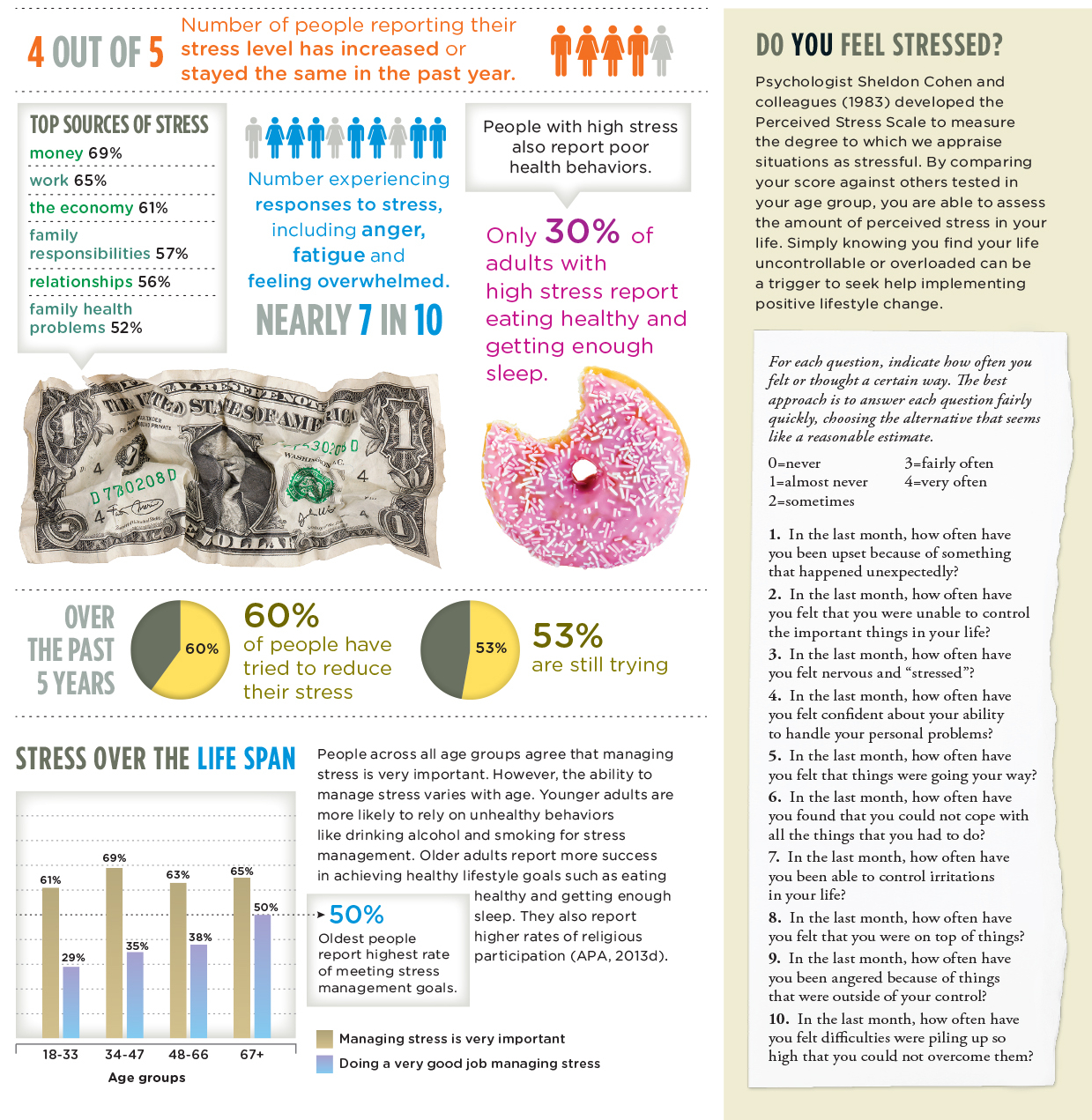

INFOGRAPHIC 12.3: Stressed Out

Every year, the American Psychological Association (APA) commissions a survey investigating perceived stress among adults in the United States. In addition to measuring attitudes about stress, the survey identifies leading sources of stress and common behaviors used to manage stressors. The resulting picture shows that stress is a significant issue for many people in the United States and that we are not always managing it well (APA, 2013d). Even when we acknowledge the importance of stress management and resolve to make positive lifestyle changes, many adults report barriers such as a lack of time or willpower that prevent them from achieving their goals. The good news? Our ability to manage stress appears to improve with age. (ALL INFORMATION PRESENTED IN THIS INFOGRAPHIC, EXCEPT THE PERCEIVED STRESS SCALE, IS FROM APA, 2013D)

Faith, Religion, and Prayer

Psychologists are also discovering the health benefits of faith, religion, and prayer. Research suggests elderly people who actively participate in religious services or pray experience improved health and noticeably lower rates of depression than those who don’t participate in such activities (Lawler-Row & Elliott, 2009; Powell, Shahabi, & Thoresen, 2003). In addition, religious affiliation is associated with increased reports of happiness and physical health (Green & Elliott, 2010).

These various types of proactive, stress-reducing behaviors reflect a certain type of attitude. You might call it a positive psychology attitude.

THINK again

Think Positive

In the very first chapter of this book, we introduced a field of study known as positive psychology, “the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, and enabling institutions” (Seligman & Steen, 2005, p. 410). Rather than focusing on mental illness and abnormal behavior, positive psychology emphasizes human strengths and virtues. The goal is well-being and fulfillment, and that means “satisfaction” with the past, “hope and optimism” for the future, and “flow and happiness” at the current time (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5).

In the very first chapter of this book, we introduced a field of study known as positive psychology, “the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, and enabling institutions” (Seligman & Steen, 2005, p. 410). Rather than focusing on mental illness and abnormal behavior, positive psychology emphasizes human strengths and virtues. The goal is well-being and fulfillment, and that means “satisfaction” with the past, “hope and optimism” for the future, and “flow and happiness” at the current time (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000, p. 5).

…YOUR CURRENT STRESS LEVEL IS WITHIN YOUR CONTROL.

As we wrap up this chapter on stress and health, we encourage you to focus on that third category: flow and happiness in the present moment. No matter what stressors come your way, try to stay grounded in the here and now. The past is the past, the future is uncertain, but this moment is yours. Finding a way to enjoy the present is one of the best ways to reduce the impact of stress. We also remind you that your current stress level is very much within your control. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, make time to engage in activities such as exercise and meditation, which produce measurable changes in the body and brain.

TO PROTECT, SERVE, AND NOT GET TOO STRESSED

If you’re wondering how Eric Flansburg and Kehlen Kirby are doing these days, both young men are thriving in their careers. Eric recently joined the police department in Cicero, New York, and is busy raising Eric Junior, 4, and baby Nathan, 11 months. It is a pleasure working in Cicero, where police officers are tightly integrated into the school community. “The kids all know me as Officer Eric,” says Eric. “I love it. Can’t see myself doing anything else.”

If you’re wondering how Eric Flansburg and Kehlen Kirby are doing these days, both young men are thriving in their careers. Eric recently joined the police department in Cicero, New York, and is busy raising Eric Junior, 4, and baby Nathan, 11 months. It is a pleasure working in Cicero, where police officers are tightly integrated into the school community. “The kids all know me as Officer Eric,” says Eric. “I love it. Can’t see myself doing anything else.”

Having worked at the fire station since 2010, Kehlen is really getting into the fire department groove. When he’s not putting out fires and rescuing people, Kehlen keeps busy helping his wife launch her own family medicine practice and trying to keep up with his daughter, Kinley, who is now nearly 2 years old. “She’s one of my biggest stress relievers,” suggests Kehlen. “Just chasing her around is enough of a stress reliever for anyone.”

show what you know

Question 12.12

1. When you must choose between two options that are equally attractive to you, this is called a(n) __________ conflict.

approach–approach

Question 12.13

2. ___________ is apparent when a person deals directly with a problem by attempting to solve it.

- Emotion-focused coping

- Positive psychology

- Support seeking

- Problem-focused coping

d. Problem-focused coping

Question 12.14

3. Individuals who are more relaxed, patient, and nonaggressive considered to have a:

- Type A personality.

- Type B personality.

- Type C personality.

- Type D personality.

b. Type B personality.

Question 12.15

4. Describe three “tools” for healthy living that you could use to improve your health.

Answers may vary. Stress management incorporates tools to lower the impact of possible stressors. Exercise, meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, and social support all have positive physical and psychological effects on the response to stressors. In addition, looking out for the well-being of others by caring and giving of yourself is an effective way to reduce the impact of stress.