13.5 Depressive Disorders

MELISSA’S SECOND DIAGNOSIS

Unfortunately for Melissa, receiving a diagnosis and treatment did not solve her problems. She hated herself for having OCD, and her parents and some friends had a hard time accepting her diagnosis. “Every day I woke up, I wanted to die,” says Melissa, who reached a breaking point during her sophomore year in high school. After a particularly difficult day at school, Melissa returned home with the intention of taking her own life. Luckily, a friend recognized that she was in distress and notified her family members, who rushed home to find Melissa curled up in a ball in the corner of her room, rocking back and forth and mumbling nonsense. They took Melissa to the hospital, where she would be safe and begin treatment. During her 3-day stay in the hospital psychiatric unit, Melissa finally met people who didn’t think she was “crazy” or define her by the disorder. For the first time, she explains, “I realized I wasn’t my disorder.”

Unfortunately for Melissa, receiving a diagnosis and treatment did not solve her problems. She hated herself for having OCD, and her parents and some friends had a hard time accepting her diagnosis. “Every day I woke up, I wanted to die,” says Melissa, who reached a breaking point during her sophomore year in high school. After a particularly difficult day at school, Melissa returned home with the intention of taking her own life. Luckily, a friend recognized that she was in distress and notified her family members, who rushed home to find Melissa curled up in a ball in the corner of her room, rocking back and forth and mumbling nonsense. They took Melissa to the hospital, where she would be safe and begin treatment. During her 3-day stay in the hospital psychiatric unit, Melissa finally met people who didn’t think she was “crazy” or define her by the disorder. For the first time, she explains, “I realized I wasn’t my disorder.”

DSM–5 and major Depressive Disorder

LO 6 Summarize the symptoms and causes of major depressive disorder.

During that hospital stay, doctors gave Melissa a new diagnosis in addition to OCD. They told her that she was suffering from depression. Apparently, the profound sadness and helplessness she had been feeling were symptoms of major depressive disorder, one of the depressive disorders described in DSM–5 (TABLE 13.5). A major depressive episode is evident if five or more of the symptoms listed below (1) occur for at least 2 consecutive weeks and represent a change from prior functioning, (2) cause significant distress or impairment, and (3) are not due to a medical or drug-related condition:

- depressed mood, which might result in feeling sad or hopeless;

- reduced pleasure in activities almost all of the time;

- substantial loss or gain in weight, without conscious effort, or changes in appetite;

- sleeping excessively or not sleeping enough;

- feeling tired, drained of energy;

- feeling worthless or extremely guilt-ridden;

- difficulty thinking or concentrating;

- persistent thoughts about death or suicide.

Someone with five or more of these symptoms would feel significantly distressed and experience problems in social interactions and at work.

In order to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, a person must have experienced at least one major depressive episode. Some people experience only one major depressive episode, and others suffer from recurrent episodes. The disorder can also be triggered by the birth of a baby. Approximately 3–6% of women experience depression starting during pregnancy or within weeks or months of giving birth; this is known as peripartum onset (APA, 2013).

When making a diagnosis, the clinician must be able to distinguish the symptoms of major depression from normal reactions to a “significant loss,” such as the death of a loved one. This is not always easy because responses to death often resemble depression. A key distinction is that grief generally decreases with time, and comes in waves associated with memories or reminders of the loss; the sadness associated with a major depressive episode tends to remain steady (APA, 2013).

| Depressive Disorder | Description | Annual Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder | Persistent irritability that typically results in “temper outbursts” and “angry mood that is present between the severe temper outbursts”. | 2–5% in children |

| Major depressive disorder | Feeling depressed (sad, empty, hopeless) almost every day for 2 weeks, or “a loss of interest or pleasure in” almost all activities. | 7% in ages 18–29 and then 3 times higher in age 60 and older |

| Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) | Feeling depressed the majority of the time: at least 2 years in adults and 1 year in children and adolescents. | 0.05% |

| Premenstrual dysphoric disorder | Feeling irritable, low, or anxious during the premenstrual phase of one’s cycle, a condition that resolves itself during menses or shortly thereafter. | 1.8–5.8% of menstruating women |

| As you can see from these descriptions, the word depression can mean many things. Some of these depressive disorders are rare, whereas others are more common. | ||

| SOURCE: DSM–5 (AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION, 2013). | ||

Major depressive disorder is one of the most common and devastating psychological disorders. In the United States, for example, the lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder is almost 17% (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005); this means that nearly 1 in 5 people experience a major depressive episode at least once in life. Women are more likely to be affected than men (Kessler et al., 2003), and rates of this disorder are already 1.5 to 3 times higher for females beginning in adolescence (APA, 2013).

The effects of major depressive disorder extend far beyond the individual. For Americans ages 15 to 44 years old, this condition is at the top of the list enumerating causes of disability (World Health Organization, 2008b)—and this means it impacts the productivity of the workforce. Major depressive disorder can result in “substantial” severity of symptoms as well as impairment in the ability to perform expected roles. In a comprehensive study of major depressive disorder, respondents reported that their symptoms prevented them from going to work or performing day-to-day activities for an average of 35 days a year (Kessler et al., 2003). Stop and think about this statistic—we are talking about a loss of 7 work weeks!

Culture

Depression is one of the most common disorders in the world, yet the symptoms experienced, the course of treatment, and the words used to describe it vary from culture to culture. For example, people in China rarely report feeling “sad,” but instead focus on physical symptoms, such as dizziness, fatigue, or inner pressure (Kleinman, 2004). In Thailand, depression is commonly expressed through physical and mental symptoms, such as headaches, fatigue, daydreaming, social withdrawal, irritation, and forgetfulness (Chirawatkul, Prakhaw, & Chomnirat, 2011).

Suicide

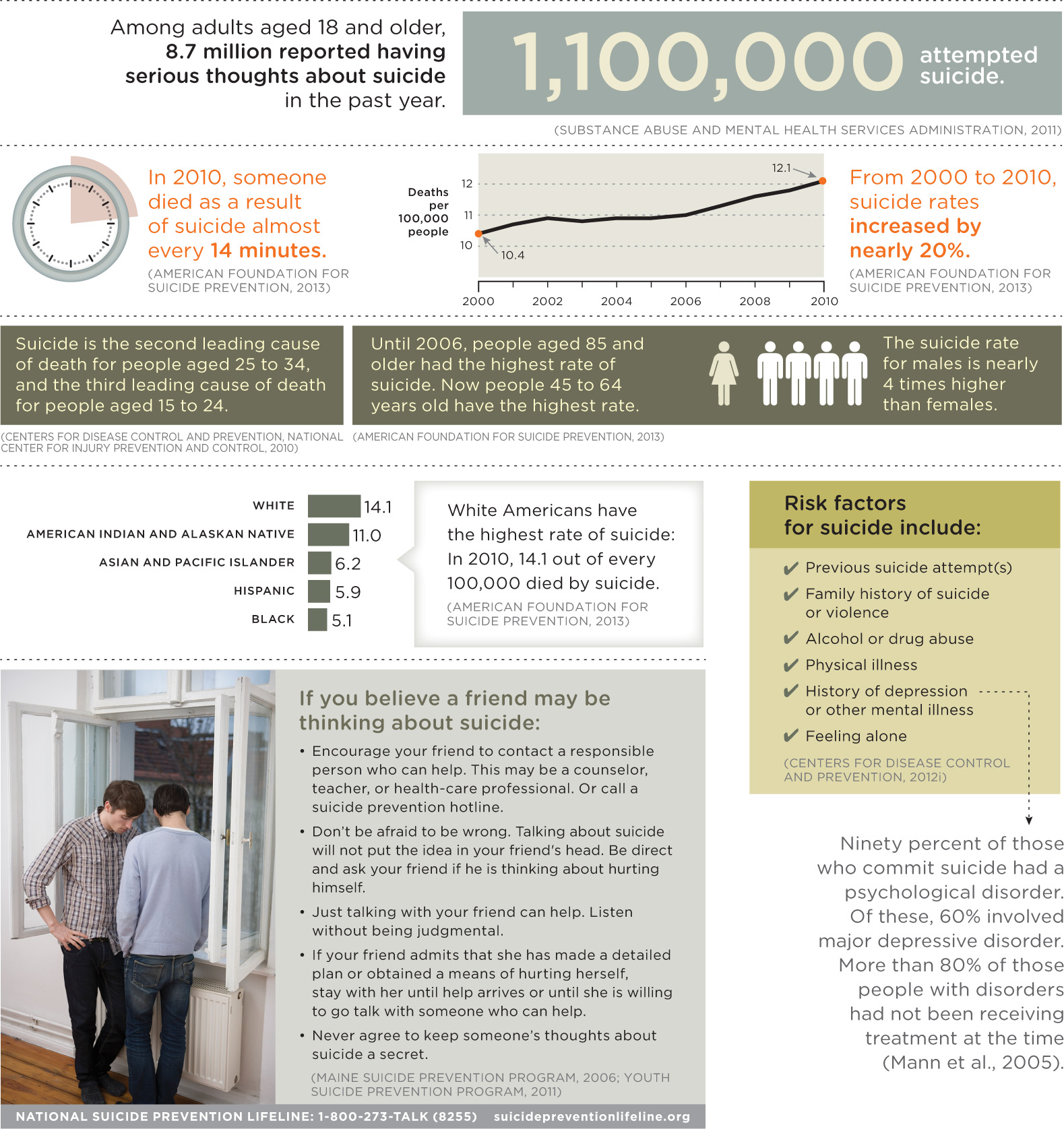

Not only is major depressive disorder a widespread condition, its recurrent nature creates increased risk for suicide and health complications (Monroe & Harkness, 2011). Around 9% of adults in 21 countries confirm they have harbored “serious thoughts of suicide” at least once (Infographic 13.2), and around 3% have attempted suicide (Borges et al., 2010). According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, 2012), approximately 90% of people who commit suicide had a psychological disorder, most commonly depressive disorder and/or substance abuse disorder.

INFOGRAPHIC 13.2: Suicide in the United States

In 2009, suicide emerged as the leading cause of death from injury in the United States, surpassing rates for homicide and traffic accidents (Rockett et al., 2012). Researchers examine suicide rates across gender, age, and ethnicity in order to better understand risk factors and to help develop suicide prevention strategies. Let’s take a look at what this means—and what you can do if a friend or family member might be contemplating suicide.

The Biology of Depression

Nearly 7% of Americans battle depression in any given year (APA, 2013; Kessler, Chiu, et al., 2005). How can we explain this staggering statistic? There appears to be something biological at work.

Genetic Factors

Studies of twins, family pedigrees, and adoptions tell us that major depressive disorder runs in families, with a heritability rate of approximately 40–50% (APA, 2013; Levinson, 2006). This means that about 40–50% of the variability of major depressive disorder in the population can be attributed to genetic factors. People who have a first-degree relative with this disorder are 2 to 4 times more likely to develop it than those whose first-degree relatives are unaffected (APA, 2013).

Neurotransmitters and the Brain

What happens inside the brain of a person who suffers from depression? Three neurotransmitters appear to be associated with the cause and course of major depressive disorder: norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine. The relationships among these neurotransmitters are complicated and research is still ongoing (El Mansari et al., 2010; Torrente, Gelenberg, & Vrana, 2012), but the findings are intriguing. For example, serotonin deficiency has been associated with major depressive disorder (Torrente et al., 2012) and genes may be responsible for some of this irregular activity, particularly in the amygdala and other brain areas involved in processing emotions associated with this disorder (Northoff, 2012).

Depression also seems to be correlated with specific structural features in the brain (Andrus et al., 2012). People with major depressive disorder may have irregularities in various parts of the brain, including the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus. For example, some regions of the right cortex show significant thinning in people who face a high risk of developing major depressive disorder (Peterson et al., 2009). Studies have zeroed in on a variety of factors, such as increased structure size, decreased volume, and changes in neural activity (Kempton et al., 2011; Sacher et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2013). Research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technologies points to irregularities in neural pathways involved in processing emotions and rewards for people with major depressive disorder (APA, 2013). The take-home message is that major depressive disorder most likely results from a complex interplay of many neural factors. What’s difficult to determine is whether changes in the brain preceded the disorder, or the disorder altered the brain.

Hormones

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described the endocrine system, which uses glands to convey messages via hormones. These chemicals released into the bloodstream can cause aggression and mood swings, as well as influence growth and alertness. Hormones may also play a role in major depressive disorder.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 12, we discussed the HPA system, which helps to maintain balance in the body by overseeing the sympathetic nervous system, the neuroendocrine system, and the immune system. The HPA system is also associated with depressive episodes.

There is also evidence that hormones play a role in depression. People with depressive disorders may have high levels of cortisol, a hormone secreted by the adrenal glands (Belmaker & Agam, 2008; Dougherty, Klein, Olino, Dyson, & Rose, 2009). Women sufferers, in particular, appear to be affected by stress-induced brain activity and hormonal fluctuations (Holsen et al., 2011). The hormonal changes associated with pregnancy and childbirth seem to be linked to major depressive episodes before or after delivery. For women suffering from these symptoms, there appear to be problems with the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) system (Corwin & Pajer, 2008; Pearlstein, Howard, Salisbury, & Zlotnick, 2009). This is not just an issue for pregnant women. Research suggests that hyperactivity of the HPA system is linked to major depressive episodes in general (APA, 2013). And, as you will soon discover, certain changes in immune activity are associated with major depressive disorder.

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Inflammation Brings on the Blues

Our immune system may mean well, but it might also cause depression

As if being stuck sick in bed wasn’t bad enough, several studies conducted during the past few years have found that the immune response to illness can cause depression. Recently scientists have pinpointed an enzyme that could be the culprit, as it is linked to both chronic inflammation—such as that found in patients with coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis—and depressive symptoms in mice.

In the new study, immunophysiologist Keith Kelley and his colleagues at the University of Illinois exposed mice to a tuberculosis vaccine that produces a low-grade, chronic inflammation. After inoculation, production in the mice brains of an enzyme called IDO, which breaks down tryptophan, spiked. The animals exhibited normal symptoms of illness such as moving around and eating less. Yet even after recovering from the physical illness induced by the vaccine, they showed signs of depression—for example, struggling less than control mice to escape from a bucket of water. Surprisingly, their listlessness was solved relatively simply. “If you block IDO, genetically or pharmaceutically, depression goes away” without interfering with the immune response, Kelley explains.

The research makes a solid case that the immune system communicates directly with the nervous system and affects important health-related behaviors such as depression. The findings could bring relief to patients afflicted with obesity, which leads to chronic inflammation, as well as to cancer patients treated with radiation and chemotherapy drugs that produce both inflammation and depression. “IDO is a new target for drug companies to aim for, to treat patients with both clinical depression and systemic inflammation,” Kelley says. Corey Binns. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2009 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Psychological Roots of Depression

Earlier we mentioned heritability rates of 40–50% for depression. But what about the other 50–60% of the variability? Clearly, biology is not everything. Psychological factors also play a role in the onset and course of major depressive disorder.

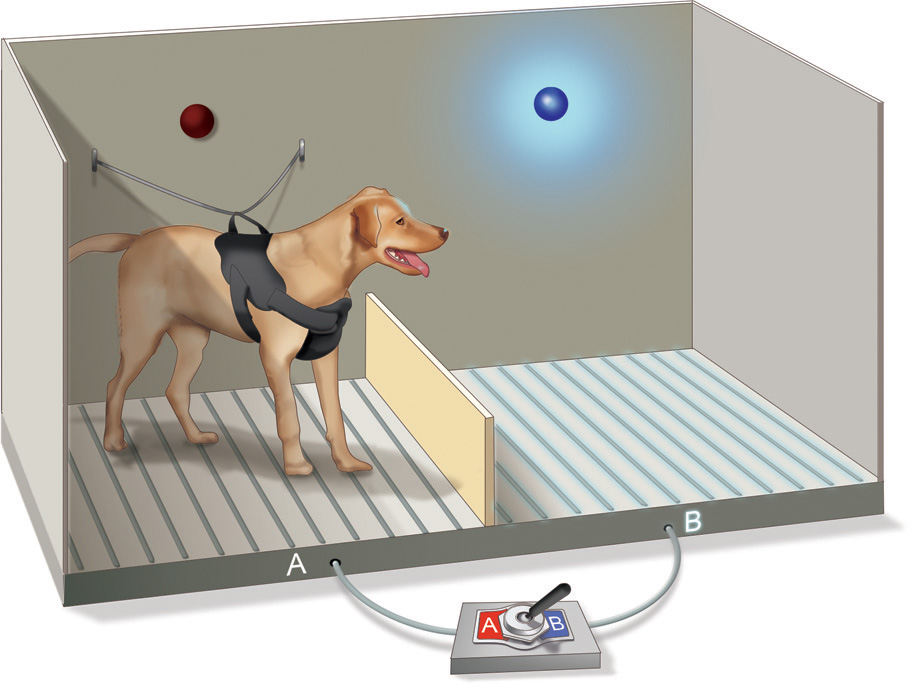

Learned Helplessness

According to researcher Martin Seligman, people often become depressed because they believe they have no control over the consequences of their behaviors (Overmier & Seligman, 1967; Seligman, 1975; Seligman & Maier, 1967). To demonstrate this learned helplessness, Seligman restrained dogs in a “hammock” and then randomly administered inescapable painful electric shocks to their paws (Figure 13.2). The next day the same dogs were put into another cage. Although unrestrained, they did not try to escape shocks administered through a floor grid (by jumping over a low barrier in the cage). Seligman concluded the dogs had learned they couldn’t control painful experiences during the prior training; they were acting in a depressed manner. He translated this finding to people with major depressive disorder, suggesting that they too feel powerless to change things for the better, and therefore become depressed.

Negative Thinking

Cognitive therapist Aaron Beck (1976) suggested that depression is connected with negative thinking. Depression, according to Beck, is the product of a “cognitive triad”—a negative view of experiences, self, and the future. Here’s an example: A student receives a failing grade on an exam, so she begins to think she is a poor student, and that belief leads her to the conclusion that she will fail the course. This self-defeating attitude may actually lead to her failing the course, reinforcing her belief that she is a poor student, and perhaps evolving into a broader belief that her life is a failure.

If you aren’t convinced that beliefs contribute to depression, consider this: The way people respond to their experience of depression may impact the severity of the disorder. People who repeatedly focus on this experience are much more likely to remain depressed and perhaps even descend into deeper depression (Eaton et al., 2012; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Women tend to ruminate or constantly think about their negative emotions more than men, rather than using “active problem solving” (Eaton et al., 2012). Yet changing negative thoughts and moods during major depressive episodes is difficult to do without help. We also should keep in mind the distinction between the risk for depression and the cause of depression, and that a correlation between rumination and depression should not be confused with a cause-and-effect relationship. Not every negative thinker develops depression, and depression can lead to negative thoughts.

We can think of mental health as a continuum, with healthy thoughts, emotions, and behaviors at one extreme, and dysfunction, distress, and deviance at the other. We can also conceptualize mood as a continuum, with depression at one end and neutral moods (not too sad, not too happy) in the center. But what lies at the other extreme? If it’s the opposite of depression, then it must be good, right? Not necessarily, as you will soon see.

show what you know

Question 13.14

1. Melissa is sleeping too much, she feels tired all of the time, and has been avoiding activities she used to enjoy. Which of the following best describes what Melissa may be experiencing?

- obsessive-compulsive disorder

- major depressive disorder

- agoraphobia

- panic attacks

b. major depressive disorder

Question 13.15

2. What neurotransmitters are associated with the cause and course of major depressive disorder?

- serotonin and norepinephrine

- serotonin and dopamine

- norepinephrine and dopamine

- serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine

d. serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine

Question 13.16

3. There are many factors involved in the cause and course of major depressive disorder. Prepare notes for a 5-minute speech you might give on this topic.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following information. The symptoms of major depressive disorder can include feelings of sadness or hopelessness, reduced pleasure, sleeping excessively or not at all, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, or difficulties thinking or concentrating. The hallmarks of major depressive disorder are the “substantial” severity of symptoms and impairment in the ability to perform expected roles. Biological theories suggest the disorder results from a genetic predisposition, neurotransmitters, and hormones. Psychological theories suggest that feelings of learned helplessness and negative thinking may play a role. Not just one factor is involved in major depressive disorder, but rather the interplay of several.