14.1 An Introduction to Treatment

treatment of psychological disorders

VOICES

An Introduction to Treatment

VOICES

It’s a beautiful evening on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in south-central South Dakota. The sun, low in the sky, casts a warm glow over pine-covered hills. Oceans of prairie grass roll in the wind. The scene could not be more tranquil. But for Chepa,) a young Lakota woman living in this Northern Plains sanctuary, life has been anything but tranquil. For days, Chepa has been tormented by the voice of a deceased uncle. Hearing voices is nothing unusual in the Lakota spiritual tradition; ancestors visit the living often. But in the case of this young woman, the voice is telling her to kill herself. Chepa has tried to make peace with her uncle’s spirit using prayer, pipe ceremony, and other forms of traditional medicine, but he will not be appeased. Increasingly paranoid and withdrawn, Chepa is making her relatives uneasy, so they take her to the home of a trusted neighbor, Dr. Dan Foster. A sun dancer and pipe carrier, Dr. Foster is a respected member of the community. He also happens to be the reservation’s lead clinical psychologist.

The story about Chepa, a Lakota woman with schizophrenia, is hypothetical, but it is based on actual scenarios that Dr. Foster encounters every week.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

after reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- LO 1 Outline the history of the treatment of psychological disorders.

- LO 2 Discuss how the main approaches to therapy differ and identify their common goal.

- LO 3 Describe how psychoanalysis differs from psychodynamic therapy.

- LO 4 Explain the concepts that form the basis of humanistic therapy.

- LO 5 Summarize person-centered therapy.

- LO 6 Describe the concepts that underlie behavior therapy.

- LO 7 Outline the concepts of cognitive therapy.

- LO 8 Identify the benefits and challenges of group therapy.

- LO 9 Compare and contrast biomedical interventions and identify their common goal.

- LO 10 Describe how culture interacts with the therapy process.

- LO 11 Summarize the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

- LO 12 Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of online psychotherapy.

Upon meeting with Chepa and her family, Dr. Foster realizes that she is having hallucinations, sensory experiences she thinks are real, but are not evident to anyone else. Chepa is also having false and irrational beliefs known as delusions. And because she is vulnerable to acting on those hallucinations and delusions, she poses a risk to herself, and possibly others. Chepa needs to go to the hospital, and it is Dr. Foster’s responsibility to make sure she gets there, even if it requires going to a judge and getting a court order. “I’m going to make an intervention,” Dr. Foster offers, “and I’m going to have to do it in a way that’s respectful to that person and to the culture, but still respectful to the body of literature and training that I come from as a psychologist.”

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we described sensation as the detection of stimuli by sensory organs. Stimuli are transduced into neural signals and sent to various parts of the brain. With hallucinations, the first step is not occurring (no apparent physical stimuli), but the sensory experience exists nevertheless. The brain interprets internal information as coming from outside the body.

Dr. Foster, in his own words:

Chepa’s grandmother protests: “I don’t want her going to the hospital. I want to use Indian medicine.” Trying to remain as clear and neutral as possible, Dr. Foster explains that traditional medicine has not worked in this case; if the voice were that of a spirit, it would have responded to prayer, pipe ceremony, and other traditional approaches. “I believe you’re hearing voices,” he says to Chepa. “But that voice is not coming from your uncle.…I think it’s coming from your own mind.” He goes on to explain that the brain has a region that specializes in hearing, and areas that store memories of people and their voices. It is possible, he explains, that the brain is calling forth a voice from the past, making it seem like it is here at this moment.

Note: Quotations attributed to Dr. Dan Foster and Laura Lichti are personal communications.

Chepa may not agree with Dr. Foster, but she trusts him. He is, after all, a relative. In Lakota culture, relatives are not necessarily linked by blood. One can be adopted into a family or community through a formal ceremony known as hunka. At Rosebud, all of the therapists and medical providers are linked to the community through hunka—a great honor and also a great responsibility.

An ambulance arrives and transports Chepa to the emergency room, where she finds Dr. Foster waiting. He is there to make a diagnosis and develop a treatment plan, but also to provide her with a sense of security, and to do so in the context of a nurturing relationship. “First of all my concern is safety, and secondly my concern is that you realize I am concerned about you,” Dr. Foster says. “We’re going to form a relationship, you and I,” he says. “Whatever it is that we’re facing, we are going to make it so that it comes out better than it is right now.”

The blood and urine screens come back negative, indicating that the hallucinations and delusions are not resulting from a drug, such as PCP or methamphetamine, and doctors find no evidence of a medical condition that could be driving the symptoms. Dr. Foster’s observations and assessments point to a complex psychological disorder known as schizophrenia.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 13, we reported that schizophrenia is a persistent and debilitating disorder that affects approximately 0.3% to 1% of the population. In this chapter, we will present some approaches to treating people with this diagnosis.

Because Chepa poses an imminent risk to herself, Dr. Foster and his colleagues arrange a transfer to a psychiatric hospital, where she may stay for several days. The medical staff will stabilize her with a drug to help reduce her symptoms, the first of many doses likely to be administered in years to come. When she returns to the reservation, Dr. Foster and his colleagues will offer her treatment, which will be designed with her specific needs in mind.

Who Gets Treatment?

CONNECTIONS

We discussed the etiology of psychological disorders in Chapter 13. The medical model implies that disorders have biological causes. The biopsychosocial approach suggests disorders result from an interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors.

Therapists working on the Rosebud Reservation tend to see clients in crises, often related to the conditions of extreme poverty that exist on Northern Plains Indian reservations. The average unemployment rate is nearly 80% (United States Senate, 2010, January 28), and affordable housing is scarce. It is not unusual to have 14 or 15 relatives packed into living quarters the size of a two-bedroom apartment. “Here we are in this beautiful, pastoral Northern Plains setting with the kind of crowding [you might] experience in New York City,” Dr. Foster says. “We’re a rural ghetto.” Squeezed into their homes without employment, entertainment, or access to transportation, people tend to feel stressed, and stress can play a role in psychological disorders. Some seek relief in alcohol, drugs, risky sex, gambling, or as Dr. Foster puts it, “outlets that [temporarily] feel good in the midst of a painful life.” Young people may turn to gangs, which can provide a sense of self-worth and belonging. Dr. Foster believes and hopes that Indian language, spiritual ceremony, and culture can act somewhat like a shield, protecting people from self-destructive behaviors. But centuries of assaults by Western society have eroded American Indian cultures.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 13, we noted that stressors can impact the course of some psychological disorders. Periods of mania, depression, and psychosis can be brought on by life changes and stressors. The diathesis–stress model suggests that a genetic predisposition and environmental triggers play a role in the development of schizophrenia.

As you may already know, the arrival of European colonists in 1492 marked the beginning of a long, drawn out attack on the physical, social, and psychological well-being of the continent’s native people. American Indians were pushed out of their native lands, relocated to reservations, economically disenfranchised, and murdered and raped by generations of American soldiers. Their children were sent away to government boarding schools, where they lost touch with their native language, religion, and culture (Struthers & Lowe, 2003). Tribal cultures are still alive, but struggling to stay afloat.

As we learn more about Dr. Foster’s work on Rosebud Reservation, be mindful that therapists work with a broad spectrum of psychological issues. Dr. Foster tends to work with people in severe distress. Some of his clients do not seek therapy, but end up in his care only because friends and relatives intervene. Other therapists spend much of their time serving those who seek help with issues such as shyness, low self-esteem, and unresolved childhood conflicts. Therapy is not just for those with psychological disorders and life catastrophes, but for anyone wishing to live a more fulfilling existence.

Psychologists use various models to explain abnormal behavior and psychological disorders. As our understanding of what causes psychological disorders has changed over time, so have treatments. While reading the brief history that follows, try to identify connections between the perceived causes of disorders and treatments designed to resolve them.

A Primitive Past: The History of Treatment

LO 1 Outline the history of the treatment of psychological disorders.

Psychological disorders and their treatments are as old as recorded history, although some of the early attempts to “cure” and “treat” them were inhumane and unproven. One theory suggests that during the Stone Age, people believed psychological disorders were caused by possession with demons and evil spirits, suggesting that our cave dweller ancestors used trephination, or drilling holes in the skull, to create exit routes for evil spirits (Maher & Maher, 2003).

Asylums or Prisons?

A major shift came in the 16th century. Religious groups began creating asylums, or special places to house and treat people with psychological disorders. However, these asylums were overcrowded and resembled prisons, with inmates chained in dungeonlike cells, starved, and subjected to sweltering heat and frigid cold. During the French Revolution (the late 1700s), Philippe Pinel, a French physician, began his work in Paris asylums. Horrified by the conditions he observed, Pinel removed the inmates’ chains and insisted they be treated more humanely (Hergenhahn, 2005; Maher & Maher, 2003). The idea of using “moral treatment,” or respect and kindness instead of harsh methods, spread throughout Europe and America (Routh & Reisman, 2003).

During the mid- to late 1800s, an American schoolteacher named Dorothea Dix vigorously championed the “mental hygiene movement,” a campaign to reform asylums in the United States. Appalled by what she witnessed in American prisons and “mental” institutions, including the caging of naked inmates, Dix helped establish and upgrade over 30 state mental hospitals (Parry, 2006). Despite the good intentions of reformers like Pinel and Dix, however, many institutions eventually deteriorated into warehouses for people with psychological disorders: overcrowded, understaffed, and underfunded. In the early 1900s, psychiatrists began to realize that mental health problems existed outside asylums, among ordinary people who were capable of functioning in society. Rather than drawing a line between the sane and insane, psychiatrists began to view mental health as a continuum. They started developing a system to classify psychological disorders based on symptoms and progression, and this effort ultimately led to the creation of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1952 (DSM; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1952; Pierre, 2012).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 13, we noted that most mental health professionals in the United States use the DSM–5. The DSM–5 is a classification system designed to help clinicians ensure accurate and consistent diagnoses based on the observation of symptoms. This manual does not include information on treatment.

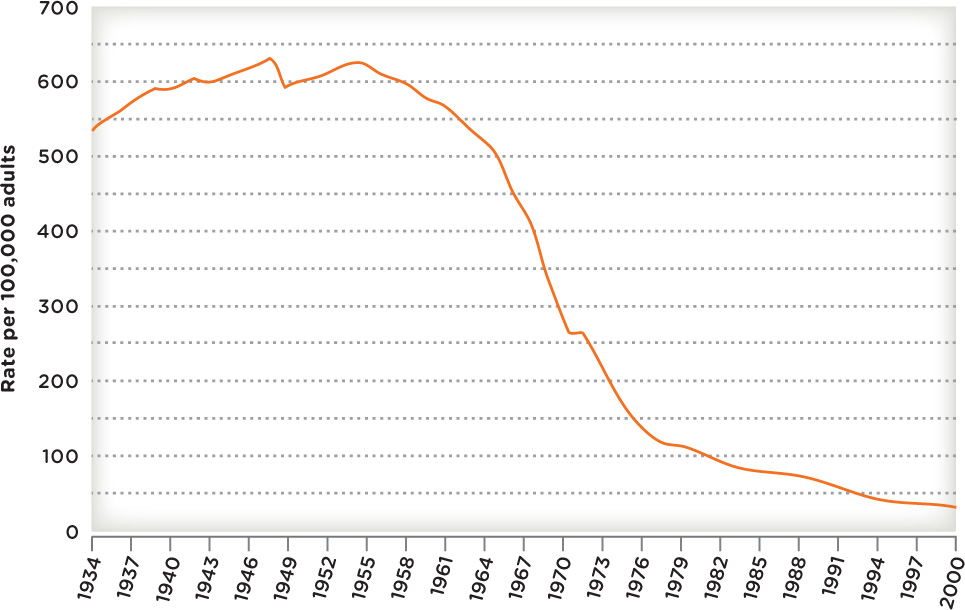

Return to the Community

The 1950s and 1960s saw a mass exodus of patients out of institutions in the United States and back into the community (Figure 14.1). This deinstitutionalization was partially the result of a movement to reduce the social isolation of people with psychological disorders and integrate them in society. Deinstitutionalization was also made possible by the introduction of medications that reduced some symptoms of severe psychological disorders. Thanks to these new drugs, many people who had previously needed constant care and supervision were able to function in society. They began caring for themselves and managing their own medications—an arrangement that worked for some but not all, as many former patients ended up living on the streets or behind bars (Harrington, 2012). By 2007 approximately 2.7 million inmates in American jails and prisons were suffering from mental health problems, representing more than one half of the inmate population (Hawthorne et al., 2012).

In spite of the deinstitutionalization movement, psychiatric hospitals and institutions continue to play an important role in the treatment of psychological disorders. The scenario involving Dr. Foster and his client Chepa may be unusual in some respects, but not when it comes to the initiation of treatment. For someone experiencing a dangerous psychotic episode, the standard approach includes a stay in a psychiatric hospital or ward. Some of these admissions are voluntary; others are not.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 13, we described psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions. Psychotic episodes can be risky for the person experiencing them—as well as those around him. In these cases, a person may be admitted to a hospital against his will. Hospitals have procedures in place to ensure that involuntary admissions are ethical.

Typically, a person is ready to leave the hospital after a few days or weeks, but many people in crisis are released after just a few hours, due to the high cost of treatment and financial pressures facing hospitals. The length of a hospital stay is often determined by what insurance will cover, rather than what a patient needs, as well as the severe shortage of available beds in psychiatric hospitals and units. Many psychiatric facilities simply cannot accommodate the scores of people seeking treatment (Honberg, Diehl, Kimball, Gruttadaro, & Fitzpatrick, 2011; Interlandi, 2012, June 22).

After being discharged from the hospital, Chepa returns home, but not everyone has family and friends who can take them in. Those needing ongoing support for their psychological disorders may live in a supervised housing facility, some providing 24-hour services, others offering support only when the need arises (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2012). Sadly, many of these mental health facilities are terribly underfunded and understaffed. We have come a long way in the treatment of psychological disorders, but there is still considerable progress to be made.

With that brief historical lesson under our belts, let’s shift our focus to contemporary treatment. These days, people receive treatment for a variety of reasons, not just mental disorders. Psychotherapy helps clients resolve work problems, cope with chronic illness, and adjust to major life changes like immigration and divorce. Some people enter psychotherapy to work on a specific issue or to improve their relationships. Let’s explore the major types of therapy used today.

Treatment Today: An Overview of Major Approaches

LO 2 Discuss how the main approaches to therapy differ and identify their common goal.

The word psychotherapy derives from the Ancient Greek psychē, meaning “soul,” and therapeuō, meaning “to heal” (Brownell, 2010), and there are many ways to go about this healing of the soul. Some therapies promote increased awareness of situations and the self; you need to understand the origins of your problems in order to deal with them. Others focus on active steps toward behavioral change. The key to resolving issues is not so much understanding their origins, but changing the thoughts and behaviors that precede them. Finally, there are interventions aimed at correcting disorders from a physical standpoint: These treatments often take the form of medication, and may be combined with psychotherapy.

Many of these approaches share common features: The relationship between the client and the treatment provider is of utmost importance, as is a sense of hope that things will get better (Snyder et al., 2000). And they generally share a common goal, which is to reduce symptoms and increase the quality of life, whether a person is struggling with a psychological disorder or simply wants to be more fulfilled.

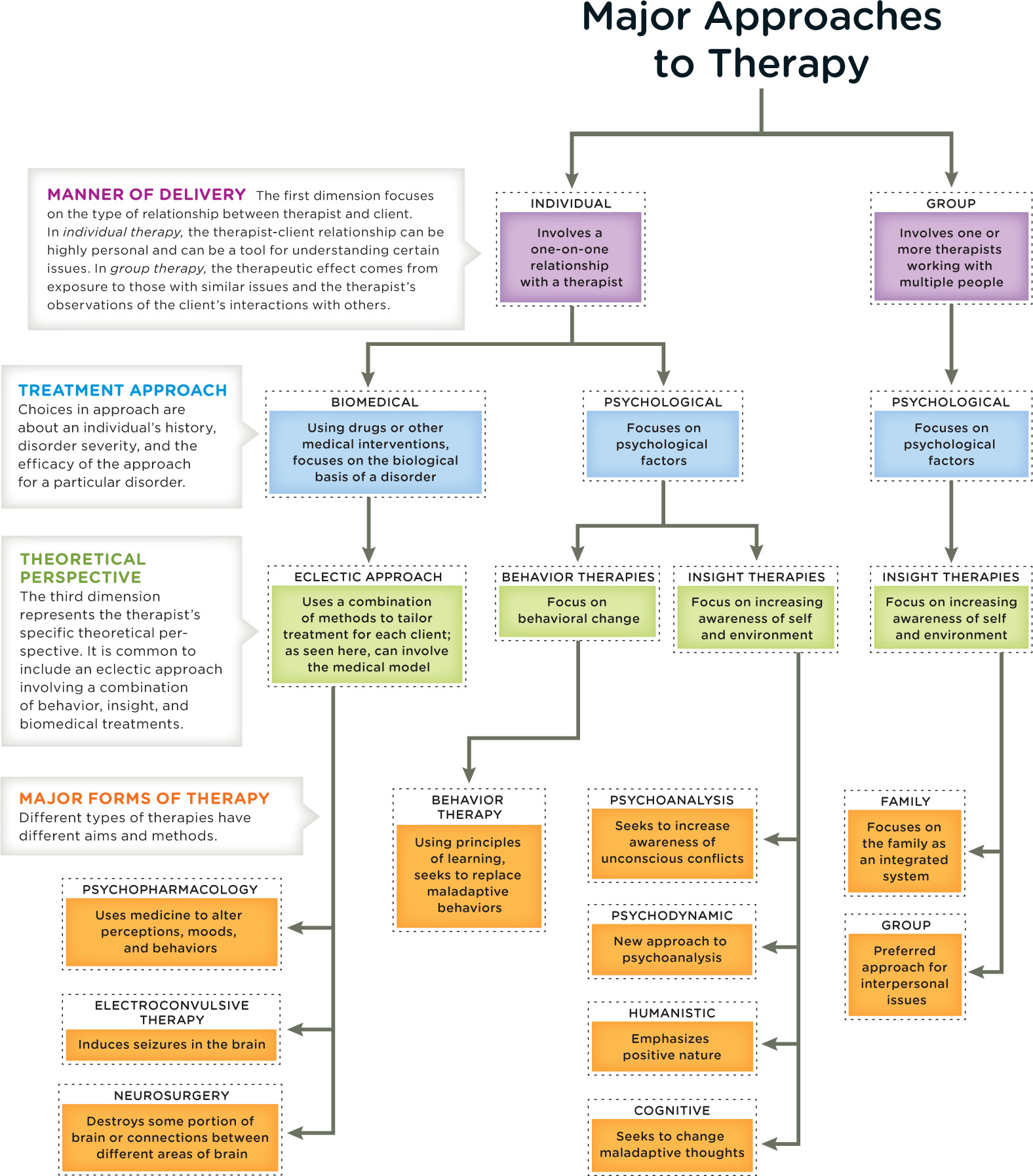

Psychological therapies can be categorized along three major dimensions. The first dimension is the manner of delivery—whether therapy is administered to an individual (one therapist working with one person) or a group (therapists working with multiple people). The second dimension is the treatment approach, which can be biomedical or psychological. Biomedical therapy refers to drugs and other medical interventions that target the biological basis of a disorder. Psychotherapy, or “talk therapy,” homes in on psychological factors. The third dimension of therapy represents the theoretical perspective or approach. We can group these approaches into two broad categories: insight therapies, which aim to increase awareness of self and the environment, and behavior therapies, which focus on behavioral change. As you learn about the many forms of therapy, keep in mind that they are not mutually exclusive; therapists often incorporate various perspectives. Around 25 to 50% of therapists today use this type of combined approach (Norcross & Beutler, 2014). Even therapists who are trained in one discipline may integrate multiple methods, tailoring treatment for each client with an eclectic approach to therapy.

INFOGRAPHIC 14.1: Major Approaches to Therapy

According to some estimates, there exist at least 500 specific types of psychotherapy (Arkowitz & Lilienfeld, 2012). Many approaches to therapy share common features, and it can be helpful to use these broad dimensions as a means of organizing our discussion. However, keep in mind that divisions between therapeutic approaches are much less rigid than it may appear in this diagram. As many as half of therapists today combine approaches, either in terms of specific techniques associated with theoretical perspectives, or in terms of the perspectives themselves (Norcross & Beutler, 2014). But for every approach the goal remains the same: to reduce symptoms and increase the quality of life.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described the importance of operational definitions. An operational definition is the precise manner in which we define and measure a characteristic of interest. Here, it is important to create an operational definition of success, which allows for the comparison of different treatment approaches.

In addition to describing the various approaches to psychological treatment, we will examine how well they work. Outcome research, which evaluates the success of therapies, is a complicated task. First, it is not always easy to pinpoint the meaning of success, or operationalize it. Should we measure self-esteem, happiness, or some other benchmark? Second, it can be difficult for clinicians to remain free of bias (both positive and negative) when reporting on the successes and failures of clients (see pages 629–630 in Chapter 15 on the self-serving bias).

In the upcoming sections, we will describe the major types of psychotherapy, beginning with the insight therapies. But first let’s take a brief detour into a seemingly unrelated, yet potentially therapeutic, activity: listening to music.

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

A Brighter Tune

Classical music may lift depressed patients’ spirits.

Add “therapist” to Beethoven’s list of talents. After listening to the master’s third and fifth sonatas, depressed patients in a recent study felt happier. The research, presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, found that classical music benefited both genders and that the music gave the biggest boost to educated and younger people.

This study supports previous findings that music therapy can be an effective and economical way to treat patients. A recently published review of the literature found that four out of five studies showed patients who had been given music therapy experienced a greater reduction in depression than those who had been randomly assigned to a different type of therapy. “Music has a specific potential that can be used therapeutically to promote well-being and alleviate symptoms like depression, anxiety, stress, anger and agitation,” reports the Beethoven study’s co-author, Pasadena City College neuroscientist Parvaneh Mohammadian. Corey Binns. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2008 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

try this

Use the Scientific American article as a way to start thinking about research on psychological therapies. Make a list of the questions that came to mind while reading it. For example, how was depression operationally defined? What other treatments did participants receive?

show what you know

Question 14.1

1. Philippe Pinel was horrified by the conditions in Parisian asylums in the late 1700s. He insisted that the inmates’ chains be removed and that they be treated with respect and kindness. This __________ then spread throughout Europe and America.

moral treatment

Question 14.2

2. A therapist writes a letter to the editor of a local newspaper in support of more funding for mental health facilities, stating that regardless of therapists’ training, all therapy shares the same goal of reducing __________ and increasing the quality of life.

- symptoms

- combined approaches

- biomedical therapy

- the number of asylums

a. symptoms

Question 14.3

3. What has been the significance of deinstitutionalization?

Deinstitutionalization was the mass movement of patients with psychological disorders out of mental institutions, in an attempt to reintegrate them into the community. Deinstitutionalization was partially the result of a movement to reduce the social isolation of people with psychological disorders. This movement marked the beginning of new treatment modalities that allowed individuals to better care for themselves and function in society. However, many former patients ended up living on the streets or behind bars. Many people locked up in American jails and prisons are suffering from mental health problems.