14.2 Insight Therapies

AWARENESS EQUALS POWER

Laura Lichti grew up in a picturesque town high in the clouds of the Rocky Mountains. Her family was, in her words, “very, very conservative,” and her church community tight-knit and isolated. As an adolescent, Laura experienced many common teenage emotions (Who am I? No one understands me), and she longed for someone to listen and understand. Fortunately, she found that safe spot in a former Sunday school teacher, a twenty-something woman with children of her own, who had a wise “old soul,” according to Laura. “The role she played for me was just like a life line,” Laura recalls. “What I appreciated is that she really didn’t direct me.” If Laura felt distressed, her mentor would never say, “I told you so.” Instead, she would listen without judgment. Then she would respond with an empathetic statement such as, “I can see that you’re having a really hard time…”

Laura Lichti grew up in a picturesque town high in the clouds of the Rocky Mountains. Her family was, in her words, “very, very conservative,” and her church community tight-knit and isolated. As an adolescent, Laura experienced many common teenage emotions (Who am I? No one understands me), and she longed for someone to listen and understand. Fortunately, she found that safe spot in a former Sunday school teacher, a twenty-something woman with children of her own, who had a wise “old soul,” according to Laura. “The role she played for me was just like a life line,” Laura recalls. “What I appreciated is that she really didn’t direct me.” If Laura felt distressed, her mentor would never say, “I told you so.” Instead, she would listen without judgment. Then she would respond with an empathetic statement such as, “I can see that you’re having a really hard time…”

With her gentle line of inquiry, the mentor encouraged Laura to search within herself for answers. Thoughtfully, empathically, she taught Laura how to find her voice, create her own solutions, and direct her life in a way that was true to herself. “[She] took it back to me,” Laura says. “It was beautiful.”

Inspired to give others what her mentor had given her, Laura resolved to become a psychotherapist for children and teens. She paid her way through community college, went on to a four-year university, and eventually received her master’s degree in psychology, gaining experience in various internships along the way. After logging in hundreds of hours of supervised training and passing the state licensing exam, Laura finally became a licensed professional counselor. The process was 10 years in the making.

Today, Laura empowers clients much in the same way her mentor empowered her—by developing their self-awareness. She knows that her therapy is working when clients become aware enough to anticipate a problem and use coping skills without her prompting. “I got into an argument and [started] getting really angry,” a client might say, “but instead of flying off the handle I took a walk and calmed down.” Developing self-awareness is one of the unifying principles of the insight therapies, which we will now explore.

Taking It to the Couch, Freudian Style: Psychoanalysis

LO 3 Describe how psychoanalysis differs from psychodynamic therapy.

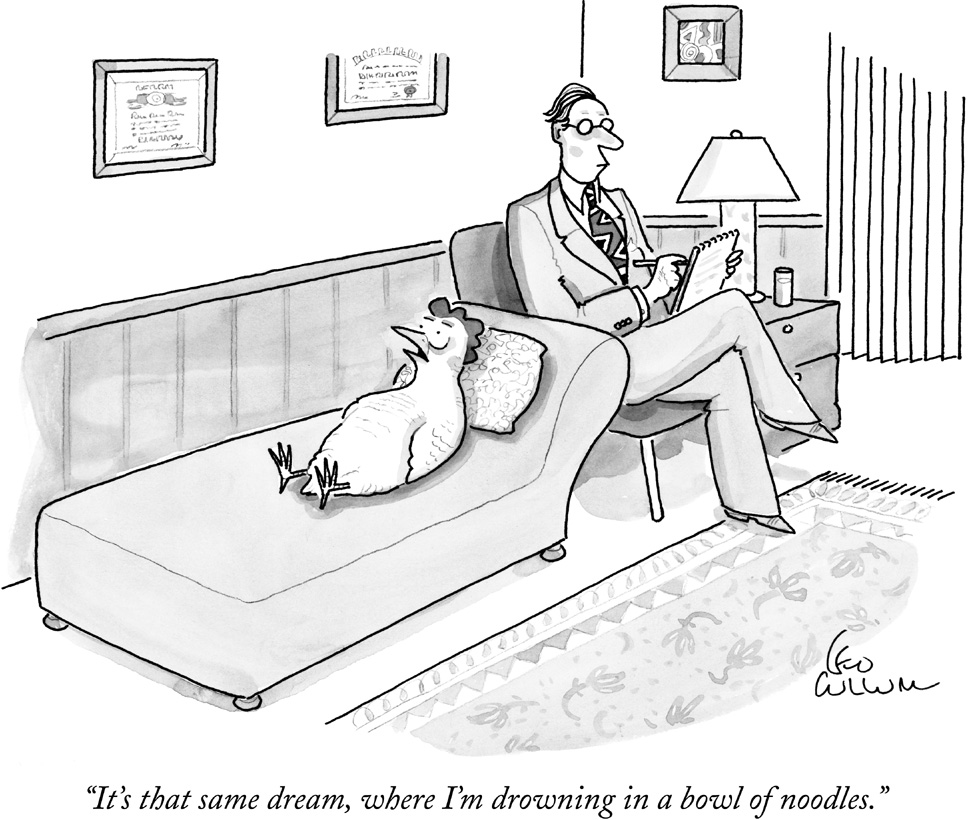

When imagining the stereotypical “therapy” session, many people often picture a person reclining on a couch and talking about dreams and memories from childhood. Modern-day therapy generally does not resemble this image. But if we could travel back in time to 1930s Vienna, Austria, and sit on Sigmund Freud’s (1856–1939) sofa, we might just see this stereotype come to life.

Freud and the Unconscious

Sigmund Freud (1900/1953), the father of psychoanalysis, proposed that humans are motivated by two animal-like drives: aggression and sex. But acting on these drives is not always compatible with social norms, so they create conflict and get pushed beneath the surface, or repressed. These drives do not just go away, though; they continue simmering beneath our conscious awareness, affecting our moods and behaviors. And when we can no longer keep them at bay, the result may be disordered behavior, such as that seen with phobias, obsessions, and panic attacks (Solms, 2006). To help patients deal with these drives, Freud created psychoanalysis, the first formal system of psychotherapy, which involved multiple weekly sessions. Psychoanalysis attempts to increase awareness of unconscious conflicts, thus making it possible to address and work through them.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we introduced the concept of repression, which is a defense mechanism through which the ego moves anxiety-provoking thoughts, memories, or feelings from consciousness to unconsciousness. Here, we will see how psychoanalysis helps uncover some of these activities occurring outside of our awareness.

Dreams, according to Freud, are a pathway to unconscious thoughts and desires brewing beneath our awareness (Freud, 1900/1953). The overt material of a dream (what we remember upon waking) is called its manifest content, which can disguise a deeper meaning, or latent content, hidden from awareness due to potentially uncomfortable issues and desires. Freud would often use dreams as a launching pad for free association, a therapy technique in which a patient says anything and everything that comes to mind, regardless of how silly, bizarre, or inappropriate it may seem.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 4, we introduced Freud’s theory of dreams. He suggested manifest content is the apparent meaning of a dream. The latent content contains the hidden meaning of a dream, representing unconscious urges. Freud believed that to expose this latent content, we must look deeper than the reported storyline of the dream.

Freud believed the seemingly directionless train of thought would lead to clues about the patient’s unconscious. Piecing together the hints he gathered from dreams, free association, and other parts of therapy sessions, Freud would identify and make inferences about the unconscious conflicts driving the patient’s behavior. He called this investigative work interpretation. When the time seemed right, Freud would share his interpretations, increasing the patient’s self-awareness and helping her come to terms with conflicts, with the aim of moving forward (Freud, 1900/1953).

You might be wondering what behaviors psychoanalysts consider signs of unconscious conflict. One indicator is resistance, a patient’s unwillingness to cooperate in therapy. Examples of resistance might include “forgetting” appointments or arriving late for them, falling asleep during free association, or becoming angry or agitated when certain topics arise. Resistance is a crucial step in psychoanalysis because it means the discussion might be veering close to something that makes the patient feel uncomfortable and threatened, like a critical memory or conflict causing distress. If resistance occurs, the job of the therapist is to help the patient identify its unconscious roots.

Another key sign of unconscious conflict is transference, a type of resistance that occurs when a patient reacts to the therapist as if she is dealing with her parents or other important people from childhood. Suppose Chepa relates to Dr. Foster as if he were a favorite uncle. She never liked letting her uncle down, so she resists telling Dr. Foster things she suspects would disappoint him. Transference is a good thing, because it illuminates the unconscious conflicts fueling a patient’s behaviors (Hoffman, 2009). One of the reasons Freud sat off to the side and out of a patient’s line of vision was to encourage transference; remaining neutral allows a patient to project his unconscious conflicts and feelings onto Freud. A therapist might experience counter-transference, projecting his own unconscious conflicts onto his patient.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we presented projective personality tests. The assumption is that the test taker’s unconscious conflicts are projected onto the test material. It is up to the therapist to try to uncover these underlying issues. Here, the patient is projecting these conflicts onto a therapist.

Taking Stock: An Appraisal of Psychoanalysis

The oldest form of talk therapy, psychoanalysis is still alive and well today. But Freud’s theories have come under sharp criticism. For one thing, they are not evidence based, meaning there is no scientific data to back them up. It is nearly impossible to evaluate effectively the subjective interpretations used in psychoanalysis. And neither therapists nor patients actually know if they are tapping the patients’ unconscious because it is made up of thoughts, memories, and desires of which we are largely unaware. How then can we know if these conflicts are being resolved? In addition, not every person is a good candidate for psychoanalysis; one must be very verbal, have time during the week for multiple sessions, and the money to pay for this often expensive therapy.

Although Freud’s theories have been undeniably criticized, the impact of his work is extensive (just note how often his work is cited in this textbook). Freud helped us appreciate how childhood experiences and unconscious processes can shape personality and behavior. Even Laura, who does not identify herself as a psychoanalyst, says that Freudian notions sometimes come into play with her clients. If a person has a traumatic experience in childhood, for example, it may resurface both in therapy and real life, she notes. Like Laura, many contemporary psychologists do not identify themselves as psychoanalysts. But that doesn’t mean Freud has left the picture. Far from it.

Goodbye, Couch; Hello, Chairs: Psychodynamic Therapy

Psychodynamic therapy is an updated take on psychoanalysis. This newer approach has been evolving over the last 30 to 40 years, incorporating many of Freud’s core themes, including the idea that personality and behaviors often can be traced to unconscious conflicts and experiences from the past.

However, psychodynamic therapy breaks from traditional psychoanalysis in important ways. Therapists tend to see clients once a week for several months rather than many times a week for years. And instead of sitting quietly off to the side of a client reclining on a couch, the therapist sits face-to-face with the client, engaging in a two-way dialogue. The therapist may use a direct approach, guiding the therapy in a clearer direction, and providing feedback and advice. Frequently, the goal of psychodynamic therapy is to understand and resolve a specific, current problem. Suppose a client finds herself in a pattern of dating abusive men. Her therapist might help her see how unconscious conflicts from the past creep into the present, influencing her feelings and behaviors (My father was abusive. Maybe I’m drawn to what feels familiar, even if it’s bad for me).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we introduced the neo-Freudians, who disagreed with Freud’s main ideas, including his singular focus on sex and aggression, his negative view of human nature, and his idea that personality is set by the end of childhood. Here, we can see that psychodynamic therapy grew out of discontent with Freud’s ideas concerning treatment.

For many years, psychodynamic therapists treated clients without much evidence to back up their methods (Levy & Ablon, 2010, February 23). But recently, researchers have begun testing the effects of psychodynamic therapy with rigorous scientific methods, and their results are encouraging. Randomized controlled trials suggest psychodynamic psychotherapy is effective for treating an array of disorders, including depression, panic disorder, and eating disorders (Leichsenring & Rabung, 2008; Milrod et al., 2007; Shedler, 2010), and the benefits may last long after treatment has ended. People with borderline personality disorder, for example, appear to experience fewer and less severe symptoms (such as a reduction in suicide attempts) for several years following psychodynamic therapy (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008; Shedler, 2010). Yet, this approach is not ideal for everyone. It requires high levels of verbal expression and awareness of self and the environment. Symptoms like hallucinations or delusions might interfere with these requirements.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described the experimental method, a research technique that can uncover cause-and-effect relationships. Here, the experimental method is used to study the outcome of therapy. In randomized controlled trials, participants are randomly assigned to treatment and control groups. The independent variable is the type of treatment, and the dependent variables are the measures of effectiveness.

You Can Do It! Humanistic Therapy

LO 4 Explain the concepts that form the basis of humanistic therapy.

For the first half of the 20th century, most psychotherapists leaned on the theoretical framework established by Freud. But in the 1950s, some psychologists began to question Freud’s dark view of human nature and his approach to treating clients. A new perspective began to take shape, one that focused on the positive aspects of human nature; this humanism would have a powerful influence on generations of psychologists, including Laura Lichti.

THE CLIENT KNOWS

During college, Laura worked as an adult supervisor at a residential treatment facility for children and teens struggling with mental health issues. The experience was eye opening. “I hadn’t really been exposed to the level of intensity, and severe needs…of that population,” Laura says. “I really had never been with people who constantly wanted to kill themselves, or had a severe eating disorder, or [who] were extreme cutters.” Laura was not a therapist at the time, so she could not offer them professional help. To connect with the residents, she relied on the relational skills she had learned from her mentor. Her message was, I’m here. I’ll meet you where you are, and I really care about you.

During college, Laura worked as an adult supervisor at a residential treatment facility for children and teens struggling with mental health issues. The experience was eye opening. “I hadn’t really been exposed to the level of intensity, and severe needs…of that population,” Laura says. “I really had never been with people who constantly wanted to kill themselves, or had a severe eating disorder, or [who] were extreme cutters.” Laura was not a therapist at the time, so she could not offer them professional help. To connect with the residents, she relied on the relational skills she had learned from her mentor. Her message was, I’m here. I’ll meet you where you are, and I really care about you.

Laura continues to use this approach in her work as a therapist, allowing each client to steer the course of his therapy. For example, Laura might begin a session by asking a client to experiment with art therapy. Some people are enthusiastic about art therapy; others resist, but Laura makes it a rule never to coerce a client with statements such as, “Well, you need to do it because I am your therapist.” Instead, she might say, “Okay, what do you think would work? If art is not going to work, what is interesting to you?” Maybe the client likes writing song lyrics; if so, Laura will follow his lead. “Okay, then why don’t you write a song for me?”

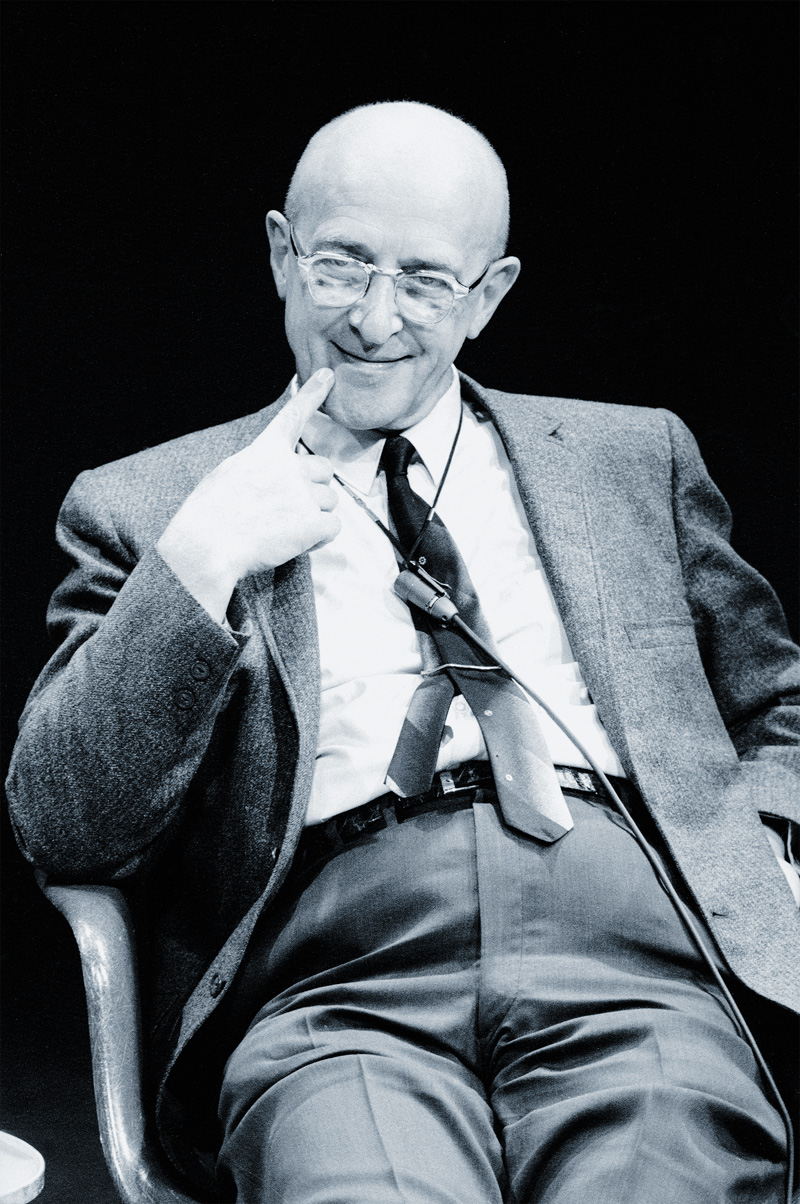

This approach to therapy is very much a part of the humanistic movement, which was championed by American psychotherapist Carl Rogers (1902–1987). Rogers believed that human beings are inherently good and inclined toward growth. “It has been my experience that persons have a basically positive direction,” Rogers wrote in his widely popular book On Becoming a Person (Rogers, 1961, p. 26). Rogers recognized that humans have basic biological needs for food and sex, but he also saw that we have powerful desires to form close relationships, treat others with warmth and tenderness, and grow and mature as individuals (Rogers, 1961).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced the field of positive psychology, which draws attention to human strengths and potential for growth. The humanistic perspective was a forerunner to this approach. As a treatment method, humanistic therapy emphasizes the positive nature of humans and strives to harness this for clients in treatment.

With this optimistic spirit, Rogers and others pioneered several types of insight therapies collectively known as humanistic therapy, which emphasizes the positive nature of humankind. Unlike psychoanalysis, which tends to focus on the distant past, humanistic therapy concentrates on the present, seeking to identify and address current problems. Rather than digging up unconscious thoughts and feelings, humanistic therapy emphasizes conscious experience: What’s going on in your mind right now?

Person-Centered Therapy

LO 5 Summarize person-centered therapy.

Rogers’ distinct form of humanistic therapy is known as person-centered therapy, and it closely follows his theory of personality. According to Rogers, each person has a natural tendency toward growth and self-actualization, or achieving one’s full potential. But factors such as expectations from family and society may stifle the process or block this tendency. He suggested these external factors often cause an incongruence, or a mismatch, between the client’s ideal self (often involving unrealistic expectations of who she should be) and real self (the way the client views herself). The main goal of treatment is to reduce the incongruence between these two selves.

Suppose Laura has a male client who is drawn toward artistic endeavors. He loves dancing, singing, and acting, but his parents believe that boys should be tough and play sports. The client has spent his life trying to become the person others expect him to be, meanwhile denying the person he is deep down, which leaves him feeling unfulfilled and empty. Using a person-centered approach, Laura would take this client on a journey toward self-actualization. She would be supportive and involved throughout the process, but she would not tell him where to go, because as Rogers stated, “It is the client who knows what hurts, what directions to go, what problems are crucial, what experiences have been deeply buried” (Rogers, 1961, p–12). This type of therapy is nondirective, in that the therapist follows the lead of the client. The goal is to help clients see they are empowered to make changes in their lives and continue along a path of positive growth.

Part of Rogers’ philosophy was his refusal to identify the people he worked with as “patients” (Rogers, 1951). Patients depend on doctors to make decisions for them, or at least give them instructions. All humans have an innate drive to become fully functioning. In Rogers’ mind, it was the patient who had the answers, not the therapist. So he began using the term client and eventually settled on the term person.

The focus in person-centered therapy is not therapeutic techniques; the goal is to create a warm and accepting relationship between client and therapist. This therapeutic alliance is based on mutual respect and caring between the therapist and the client, and provides a safe place for self-exploration.

At this point, you may be wondering what exactly the therapist does during sessions. If a client has all the answers, why does he need a therapist at all? Sitting face-to-face with a client, the therapist’s main job is to “be there” for that person through empathy, unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and active listening, all of which are essential for building a therapeutic alliance (TABLE 14.1).

| Components of the Therapeutic Alliance | Description |

| Empathy | The ability to feel what a client is experiencing; seeing the world through the client’s eyes (Rogers, 1951); therapist perceives feelings and experiences from “inside” the client (Rogers, 1961) |

| Unconditional positive regard | Total acceptance of a client no matter how distasteful the client’s behaviors, beliefs, and words may be (Chapter 11) |

| Genuineness | Being authentic, responding to a client in a way that is real rather than hiding behind a polite or professional mask; knowing exactly where the therapist stands allows the client to feel secure enough to open up (Rogers, 1961) |

| Active listening | Picking up on the content and emotions behind words in order to understand a client’s point of view; reflection or echoing the main point of what a client says |

| Humanist Carl Rogers believed it was critical to establish a strong and trusting therapist–client relationship. Above are the key elements of a therapeutic alliance. | |

Taking Stock: An Appraisal of Humanistic Therapy

The humanistic perspective has had a profound impact on our understanding of personality development and on the practice of psychotherapy. Therapists of all different theoretical orientations draw on humanistic techniques to build stronger relationships with clients and create positive therapeutic environments. This type of therapy is useful for an array of people dealing with complex and diverse problems (Corey, 2013), but how it compares to other methods remains somewhat unclear. Studying humanistic therapy is difficult because its methodology has not been operationalized and its use varies from one therapist to the next. Like other insight therapies, humanistic therapy is not ideal for everyone; it requires a high level of verbal skills and self-awareness.

The insight therapies we have explored—psychoanalysis, psychodynamic therapy, and humanistic therapy—help clients develop a deeper understanding of self. By exploring events of the past, clients in psychoanalysis or psychodynamic therapy may discover how prior experiences affect their current thoughts and behaviors. Those working with humanistic therapists may become more aware of what they want in life—and how their desires conflict with the expectations of others. These insights are invaluable, and they often lead to positive changes in behavior. But is it also possible to alter behavior directly? This is the goal of behavior therapy, the subject of the next section.

show what you know

Question 14.4

1. Suzanne is late for her therapy appointment yet again. Her therapist suggests this might be due to __________, which generally refers to a patient’s unwillingness to cooperate in therapy.

resistance

Question 14.5

2. The group of therapies known as __________ therapy focus on the positive nature of human beings and on the here-and-now.

- humanistic

- psychoanalytic

- psychodynamic

- free association

a. humanistic

Question 14.6

3. Seeing the world through a client’s eyes and understanding how it feels to be the client is called

- interpretation.

- genuineness.

- empathy.

- self-actualization.

c. empathy.

Question 14.7

4. What are the differences between psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapy?

Psychoanalysis, the first formal system of psychotherapy, attempts to increase awareness of unconscious conflicts, making it possible to address and work through them. The therapist’s goal is to uncover these unconscious conflicts. Psychodynamic therapy is an updated form of psychoanalysis; it incorporates many of Freud’s core themes, including the notion that personality characteristics and behavior problems often can be traced to unconscious conflicts. In psychodynamic therapy, therapists see clients once a week for several months rather than many times a week for years. And instead of sitting quietly off to the side, therapists and clients sit face-to-face and engage in a two-way dialogue.