14.6 Biomedical Therapies

Earlier in the chapter, we described Dr. Foster’s work with Chepa, the young woman with schizophrenia. After being discharged from the hospital, Chepa returns to her family, but her treatment is far from over. In addition to receiving psychotherapy, Chepa will most likely go to the medical clinic for monthly injections of drugs to control her psychosis. Prescribing medications for psychological disorders is generally the domain of psychiatrists, physicians who specialize in treating people with psychological disorders (psychiatrists are medical doctors, whereas clinical psychologists have PhDs and generally cannot prescribe medication).

LO 9 Compare and contrast biomedical interventions and identify their common goal.

People with severe disorders like depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder often benefit from biomedical therapy, a type of treatment that targets the biological processes underlying psychological disorders. There are three basic biological approaches to treating psychological disorders: (1) the use of drugs, or psychotropic medications; (2) the use of electroconvulsive therapy; and (3) the use of surgery.

Medicines That Help: Psychopharmacology

Psychotropic medications are used to treat psychological disorders and their symptoms. Psychopharmacology is the scientific study of how these medications alter perceptions, moods, behaviors, and other aspects of psychological functioning. These drugs can be divided into four categories: antidepressant, mood-stabilizing, antipsychotic, and antianxiety.

Antidepressant Drugs

The primary reason people come to Dr. Foster seeking psychological help is major depressive disorder. Commonly referred to as depression, it is one of the most prevalent psychological disorders in America and a common cause of disability in young adults (National Institute of Mental Health, 2012). Major depressive disorder affects around 7% of the population in any given year (APA, 2013), resulting in a high demand for ways to lessen its symptoms.

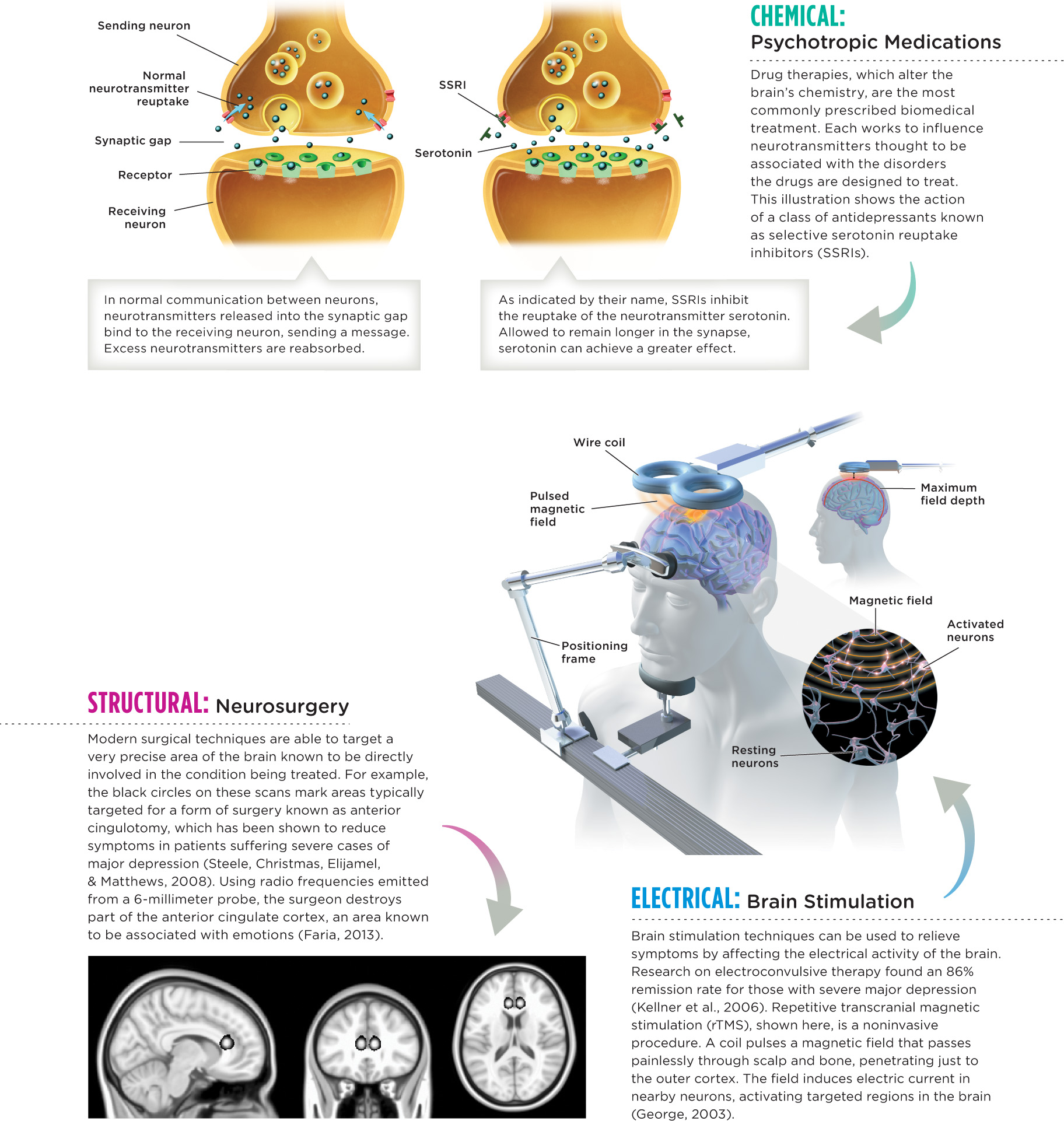

Major depressive disorder is commonly treated with antidepressant drugs, a category of psychotropic medication used to improve mood (and to treat anxiety and eating disorders in certain individuals). Essentially, there are three classes of antidepressant drugs: monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as Nardil; tricyclic antidepressants, such as Elavil; and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as Prozac. All these antidepressants are thought to work by influencing the activity of neurotransmitters that are hypothesized to be involved in depression and other disorders (Infographic 14.3). (Keep in mind, no one has pinpointed the exact neurological mechanisms underlying depression.)

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described how neurons communicate with each other. Sending neurons release neurotransmitters into the synaptic gap, where they bind to receptors on the receiving neuron. Neurotransmitters not immediately attached are reabsorbed by the sending neuron (reuptake) or are broken down in the synapse. Here, we see how medications can influence this process.

The monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), developed in the 1950s, help people with major depressive disorder by slowing the breakdown of norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine in synapses (these neurotransmitters are categorized as monoamines). The natural role of the enzyme monoamine oxidase is to break down the monoamines when they are in the synaptic gap. MAOIs extend the amount of time these neurotransmitters linger in the gap by hindering the normal activity of monoamine oxidase. It is not clear how the monoamine neurotransmitters interact to cause depression, but by making them more available (that is, allowing them more time in the synapse), symptoms of depression can be lessened. This group of antidepressants reduces depression, but they have fallen out of use due to safety concerns and side effects, as they require great attention to diet. MAOIs can trigger a life-threatening jump in blood pressure when ingested alongside tyramine, a substance found in many everyday foods including cheddar cheese, salami, and wine (Anastasio et al., 2010; Blackwell, Marley, Price, & Taylor, 1967; Horwitz, Lovenberg, Engelman, & Sjoerdsma, 1964; Rosenberg & Kosslyn, 2011).

The tricyclic antidepressants, named as such because of their three-ringed molecular structure, inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin in the synaptic gap. Again, the cause of depression is not clear, but if a lack of serotonin and norepinephrine is involved, allowing them longer time to be active appears to reduce symptoms. The tricyclic drugs are not always well tolerated by patients and can cause a host of problematic side effects, including sexual dysfunction, confusion, and increased risk of heart attack (Cohen, Gibson, & Alderman, 2000; Higgens, Nash, & Lynch, 2010). Overdoses can be fatal.

Doctors relied heavily on monoamine oxidase inhibitors and tricyclics until newer, more popular pharmaceutical interventions were introduced in the 1980s. These selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) include brands such as Prozac, Paxil, and Zoloft. SSRIs also impede reuptake, but this class of drug inhibits the reuptake of serotonin specifically.

SSRIs are generally safer and have fewer negative effects than the older generation of antidepressants, which helps explain why they have become so popular in recent decades. But they are far from perfect. Weight gain, fatigue, hot flashes and chills, insomnia, nausea, and sexual dysfunction are all possible side effects. Some research suggests that they work no better than a placebo when it comes to treating mild to moderate depression (Fournier et al., 2010). But these drugs can be very beneficial in reducing the potentially devastating symptoms of depression. Improvement is generally noticed within 3–5 weeks after treatment has started.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we stated that a placebo is a “pretend” treatment used to explore the effectiveness of a “true” treatment. The placebo effect is the tendency to feel better if we believe we are being treated with a medication. Expectations about getting better can change treatment outcomes.

Mood-Stabilizing Drugs

In Chapter 13, we introduced Ross Szabo, a man who suffers from bipolar disorder. Ross has battled extreme mood swings in his life—the highest highs and the lowest lows. Many people suffering from bipolar disorder find some degree of relief in mood-stabilizing drugs, which can minimize the lows of depression and the highs of mania. Lithium, for instance, helps smooth the mood swings of people with bipolar disorder, leveling out the dramatic peaks (mania) and valleys (depression). For this reason, it is sometimes called a “mood normalizer” (Bech, 2006) and has been widely used to treat bipolar disorder for decades. Unlike standard drugs that chemists cobble together in laboratories, this drug is a mineral salt, in other words, a naturally occurring substance. (You can find lithium in the Periodic Table of the Elements—just look for the symbol Li.)

Scientists have yet to determine the cause of bipolar disorder and how its symptoms might be lessened with lithium. But numerous theories exist, some pointing to imbalances in neurotransmitters such as glutamate and serotonin (Cho et al., 2005; Dixon & Hokin, 1998). Lithium also seems to be effective in lowering suicide risk among people with bipolar disorder (Angst, Angst, Gerber-Werder, & Gamma, 2005), who are 20 times more likely than people in the general population to take their own lives (Tondo, Isacsson, & Baldessarini, 2003). Doctors must be very careful when prescribing lithium, monitoring the blood levels of patients who use it. Too small a dose will fall short of controlling bipolar symptoms, whereas one that is too large can be lethal. Even when the amount is just right, mild side effects such as hand tremors, thirst, and nausea may occur (National Institute of Mental Health, 2007).

Anticonvulsant medications are also used to treat bipolar disorder. Originally created to treat seizure disorders, scientists discovered they might also be used as mood stabilizers, and some research suggests that they can reduce the symptoms of mania (Bowden et al., 2000). Unfortunately, certain anticonvulsants may increase the risk of suicide or possible suicide masked as violent death through injury or accident (Patorno et al., 2010). For this reason, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (USFDA, 2008) requires drug companies to place warnings on their labels.

Antipsychotic Drugs

The hallucinations and delusions of people with disorders like schizophrenia can be subdued with antipsychotics. Antipsychotic drugs are designed to block neurotransmitter receptors. Although it is not entirely clear how neurotransmitters cause the symptoms of schizophrenia, blocking these receptor sites reduces the activity of neurons presumably associated with psychotic symptoms.

Two kinds of medications can be used in these cases: traditional antipsychotic medications and atypical antipsychotics (each with about a half-dozen generic drug offshoots). Both types seek to reduce dopamine activity in certain areas of the brain, as dopamine is a neurotransmitter believed to contribute to the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia and other disorders (Schnider, Guggisberg, Nahum, Gabriel, & Morand, 2010). Antipsychotics accomplish this by acting as dopamine antagonists, meaning they “pose” as dopamine, binding to receptors normally reserved for dopamine (sort of like stealing someone’s parking space). By blocking dopamine’s receptors, antipsychotic drugs reduce dopamine’s excitatory effect on neurons. The main difference between atypical antipsychotics and the traditional variety is that the atypical antipsychotics also interfere with neural pathways involving other neurotransmitters, such as serotonin (which is associated with psychotic symptoms as well).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described how drugs influence behavior by changing what is happening in the synapse. Agonists increase the normal activity of a neurotransmitter, and antagonists block normal neurotransmitter activity. Here we see how psychotropic medications alter activity in the synapse.

First rolled out in the 1950s, traditional antipsychotics, such as Haldol, made it possible for scores of people to transition out of psychiatric institutions and into society. These new drugs reduced hallucinations and delusions for many patients, but doctors soon realized that they had other, not-so-desirable effects. After taking the drugs for about a year, some patients developed a neurological condition called tardive dyskinesia, the symptoms of which include shaking, restlessness, and bizarre grimaces.

These problems were partially solved with the development of the atypical antipsychotics, such as Risperdal (risperidone), which reduce psychotic symptoms and usually do not cause tardive dyskinesia (Correll, Leucht, & Kane, 2004). But there are other potential side effects, such as weight gain, increased risk for Type 2 diabetes, sexual dysfunction, and heart disease (Ücok & Gaebel, 2008). And although these drugs reduce the symptoms in 60–85% of patients, they are not a cure for the disorder.

Antianxiety Drugs

Anxiety disorders are the second most common class of conditions Dr. Foster encounters on the reservation. Like many impoverished areas, Rosebud has a high rate of trauma (for example, alcohol-associated accidents and homicides). In the United States, the suicide rate among American Indian and Alaska Native youth (ages 10 to 24) exceeds that of all other racial groups. Youth suicides have increased substantially over the last two decades (Dorgan, 2010). Researchers have tried to untangle the complex web of factors responsible for the deeply troubling statistics, but few would question its connection to the centuries of psychological and cultural damage wrought by colonization. Physical and sexual assault by occupying soldiers, destruction of tribal culture and spirituality by three generations of Indian boarding schools, and ongoing marginalization and discrimination—these types of realities do not just fade away. Traumatic incidents like suicides inevitably have witnesses, and those witnesses suffer from what they see and hear. Their pain often manifests itself in the form of anxiety.

Antianxiety drugs are used to treat the symptoms of anxiety and anxiety disorders including panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety disorder. Most of today’s antianxiety medications are benzodiazepines, such as Xanax and Ativan, or “minor tranquilizers.” These minor tranquilizers are used for a continuum of anxiety, from fear of flying to extreme panic attacks. And since these drugs promote sleep in high doses, they can also be used to treat insomnia. Doctors often prescribe benzodiazepines in combination with other psychotropic medications.

Valium is one of the most commonly used minor tranquilizers, and it was the first psychotropic drug to be used by people who were not necessarily suffering from serious disorders. For most of the 1970s, Valium was so popular among white collar businessmen and women that it came to be called “Executive Excedrin.” But then people began to realize how dependent they had become on Valium, both physically and psychologically, and its popularity diminished (Barber, 2008). Nevertheless, medications such as Valium and Xanax are still the most commonly abused antianxiety drugs (Phillips, 2013).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 4, we discussed psychoactive drugs. Physiological dependence can occur with constant use of some drugs, indicated by tolerance and withdrawal symptoms. Psychological dependence is apparent when a strong desire or need to continue using a substance occurs, but without tolerance or withdrawal symptoms.

A key benefit of benzodiazepines is that they are fast acting. But they are also dangerously addictive, and mixing them with alcohol can produce a lethal cocktail. Benzodiazepines ease anxiety by enhancing the effect of the neurotransmitter GABA. An inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA works by decreasing or stopping some neural activity. By giving GABA a boost, these drugs inhibit the firing of neurons that normally induce anxiety reactions.

Psychotropic Medication Plus Psychotherapy

Psychotropic medications have helped countless people get back on their feet and enjoy life, but many believe that drugs alone don’t produce the best long-term outcomes. Ideally, medications should be taken in conjunction with psychotherapy. With therapy, Dr. Foster says, “The person feels greater self-efficacy. They’re not relying on a pill to manage depression.”

Indeed, studies suggest that psychotropic drugs are most effective when used alongside psychotherapy. Researchers have shown that combining medication with an integrative approach to psychotherapy, including cognitive, behavioral, and psychodynamic perspectives, reduces major depressive symptoms faster than either approach alone (Manber et al., 2008).

Dr. Foster: How might medication impact the effectiveness of psychotherapy?

Another key point to remember: Medications affect people in different ways. An antidepressant that works for one person may have no effect on another; this is also the case for side effects. We metabolize (break down) drugs at different rates, which means dosages must be assessed on a case-by-case basis. To complicate matters further, many people take multiple medications at once, and some drugs interact in harmful ways.

INFOGRAPHIC 14.3: Biomedical Therapies

Biomedical therapies use physical interventions to treat psychological disorders. These therapies can be categorized according to the method by which they influence the brain’s functioning: chemical, electrical, or structural.

When Drugs Aren’t Enough: The Other Biomedical Therapies

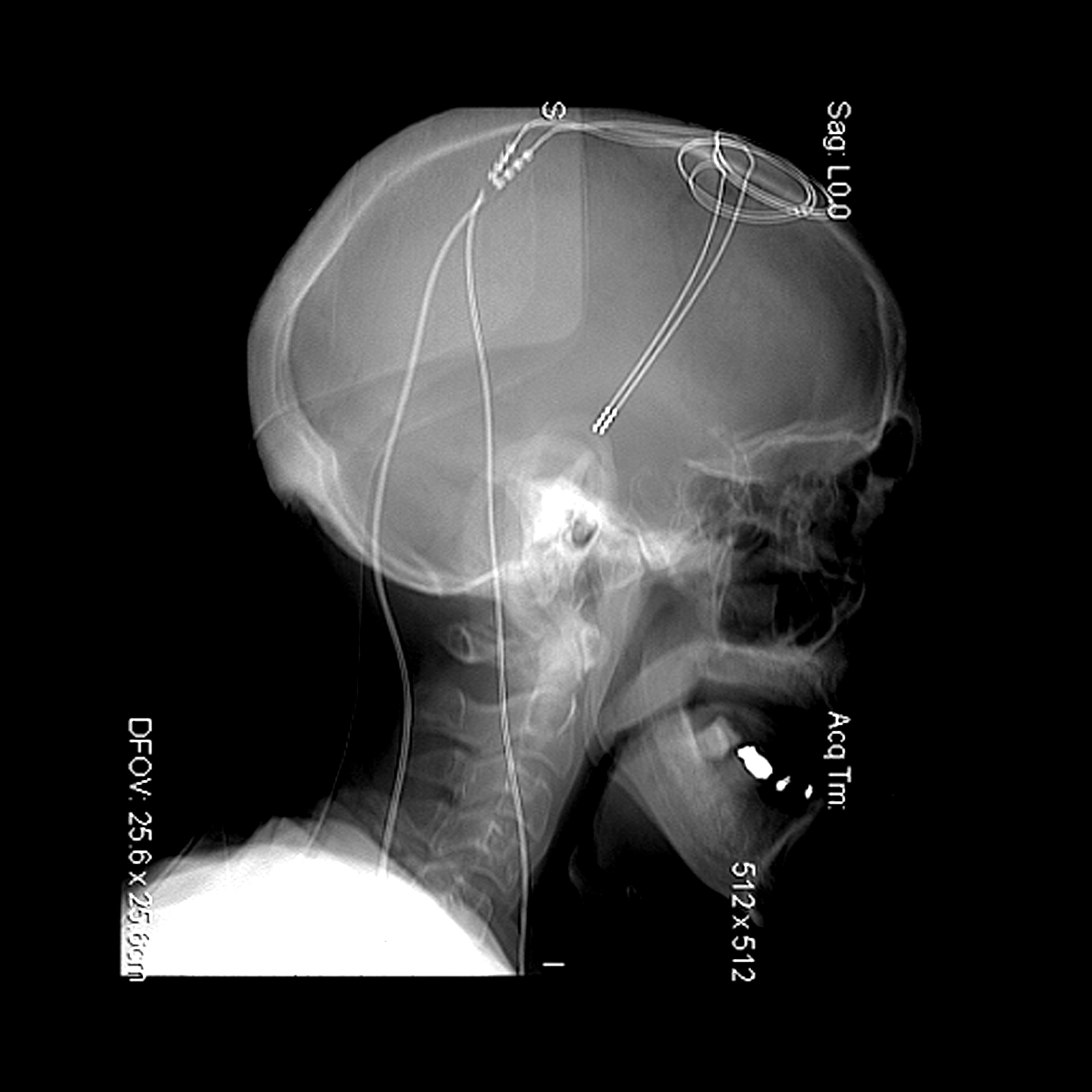

As you likely have guessed from this section, psychotropic drugs are not a cure-all. Sometimes symptoms of psychological disorders do not improve with medication. In these extreme cases, there are other biomedical options. For example, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) appears to be effective in treating symptoms of depression and some types of hallucinations. With rTMS, electromagnetic coils are put on (or above) a person’s head, directing brief electrical current into a particular area of the brain (Slotema, Blom, Hoek, & Sommer, 2010). Another technique under investigation is deep brain stimulation, which involves implanting a device that supplies weak electrical stimulation to specific areas of the brain thought to be linked to depression (Kennedy et al., 2011; Schlaepfer, Bewernick, Kayser, Mädler, & Coenen, 2013). These new techniques show great promise, but more research is required to determine their long-term impact.

Electroconvulsive Therapy

One biomedical approach that essentially causes seizures in the brain is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which is used with severely depressed people who have not responded to psychotropic medications or psychotherapy. If you’ve ever seen ECT or “shock therapy” portrayed in movies, you might think it’s a barbaric form of abuse. Truth be told, ECT was a brutal and overly used treatment in the mid-20th century (Glass, 2001; Smith, 2001). Doctors jolted patients (in some cases a dozen times a day) with powerful currents, creating seizures violent enough to break bones and erase weeks or months of memories (Smith, 2001). Today, ECT is much more humane, administered according to guidelines developed by the American Psychiatric Association (2001). Patients take painkillers and muscle relaxants before the treatment, and general anesthesia can be used during the procedure. Furthermore, the electrical currents are weaker, inducing seizures only in the brain. Patients in the United States typically get three treatments per week for up to a month (Glass, 2001).

Scientists don’t know exactly how ECT reduces the symptoms of depression, although a variety of theories have been proposed (Cyrzyk, 2013). And despite its enduring “bad rap,” ECT can be an effective treatment for depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia for people who haven’t responded well to psychotherapy or drugs (Baker, 2009, January 8; Glass, 2001). Yet in the United States, the number of patients admitted to a hospital for ECT treatment in 2009 was 7.2 per 100,000 adults, which represented a substantial decline over the years (Case et al., 2013). The major downside of ECT is its tendency to induce confusion and memory loss, including anterograde and retrograde amnesias (APA, 2001; Fink & Taylor, 2007; Read & Bentall, 2010).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 6, we discussed amnesia, which is memory loss resulting from physical or psychological conditions. Retrograde amnesia is the inability to access old memories; anterograde amnesia is the inability to make new memories. ECT can cause these types of amnesia, which is one reason the American Psychiatric Association developed guidelines for this treatment (2001).

Neurosurgery

One extreme option for patients who don’t show substantial improvement with psychotherapy or psychotropic drugs is neurosurgery, which destroys some portion of the brain or connections between different areas of the brain. Like ECT, neurosurgery is tarnished by an unethical past. During the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, doctors performed prefrontal lobotomies, destroying part of the frontal lobes or disconnecting them from lower areas of the brain (Kucharski, 1984). But lobotomy outcomes were mixed at best. These operations can lead to severe side effects, including permanent impairments to everyday functioning. In the past, this procedure had no precision, often resulting in permanent personality changes and diminished function. The consequences of lobotomy were often worse than the disorders they aimed to fix. The popularity of the surgery plummeted in the 1950s when the first-generation antipsychotics were introduced, offering a safer alternative to psychosurgery (Mashour, Walker, & Martuza, 2005).

Brain surgeries are only used to treat psychological disorders as a last resort, and they are far more precise than the archaic lobotomy. Surgeons home in on a small target, destroying only tiny tracts of tissue. One of these surgeries has been a lifesaver for a select few suffering from a severe, drug-resistant form of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), but the precise effects have yet to be determined (Mashour et al., 2005). People suffering from severe seizure disorders sometimes undergo split-brain operations—the surgical disconnection of the right and left hemispheres. With the corpus callosum severed, the two hemispheres are disconnected, preventing the spread of electrical storms responsible for seizures. These more invasive biomedical therapies are seldom used, but they can make a difference in the quality of life for some individuals.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we discussed the use of the split-brain operation to treat drug-resistant seizures. When the hemispheres are disconnected, researchers can study them separately to explore their unique capabilities. People who undergo this operation have fewer seizures, and can have normal cognitive abilities and no obvious changes in temperament or personality traits.

Taking Stock: An Appraisal of Biomedical Therapy

Medications and other biomedical treatments can reduce the symptoms of major psychological disorders. In fact, psychotropic drugs work so well that their introduction led to the deinstitutionalization of thousands of people. But it would be a mistake to think of these biological interventions as a cure-all, as this deemphasizes the importance of the other two components of the biopsychosocial model: psychological and social factors. Furthermore, research on the long-term outcomes of many of these treatments remains inconclusive.

show what you know

Question 14.18

1. A young man is taking psychotropic medications for major depression, but the drugs do not seem to be alleviating his symptoms. Which of the following biomedical approaches might his psychiatrist try next?

- split-brain operation

- prefrontal lobotomy

- tardive dyskinesia

- electroconvulsive therapy

d. electroconvulsive therapy

Question 14.19

2. Psychotropic drugs can be divided into four categories, including mood-stabilizing, antipsychotic, antianxiety drugs, and

- mood normalizers.

- antidepressants.

- antagonists.

- atypical antipsychotics.

b. antidepressants.

Question 14.20

3. One treatment option used for individuals who do not show substantial improvement with psychotherapy or psychotropic drugs is __________, which destroys some portion of the brain or connections between different areas of the brain.

neurosurgery

Question 14.21

4. How do biomedical interventions differ from psychotherapy? Compare their goals.

Answers will vary. Biomedical therapies use physical interventions to treat psychological disorders. These therapies can be categorized according to the method by which they influence the brain’s functioning: chemical, electrical, or structural. Psychotherapy is a treatment approach in which a client works with a mental health professional to reduce psychological symptoms and increase his or her quality of life. These approaches share common features: The relationship between the client and the treatment provider is of utmost importance, as is a sense of hope that things will get better. And these approaches generally seek to reduce symptoms and increase the quality of life, whether a person is struggling with a psychological disorder or simply wants to be more fulfilled.