15.3 Social Influence

11 ORPHANS

In 1983 a 7-year-old boy in northern Uganda came down with the measles. The child was feverish and coughing, and his skin was covered in a blotchy rash. He appeared to be dying. In fact, he did die—or so the local villagers believed. They dug his grave, wrapped him in a burial cloth, and sang him a farewell song. Then, just as they were about to lower the body into the ground, someone heard a sneeze. A few moments later, another sneeze. Could it be? The body inside the burial cloth started to writhe. Hastily unwrapping the cloth, the mourners found the child frantically kicking and crying. It’s a good thing the boy sneezed that day at his funeral, as the world is a much happier place because he survived. His name is Julius Achon, and he would grow up to become an Olympic athlete and, perhaps more important, a world-class humanitarian.

In 1983 a 7-year-old boy in northern Uganda came down with the measles. The child was feverish and coughing, and his skin was covered in a blotchy rash. He appeared to be dying. In fact, he did die—or so the local villagers believed. They dug his grave, wrapped him in a burial cloth, and sang him a farewell song. Then, just as they were about to lower the body into the ground, someone heard a sneeze. A few moments later, another sneeze. Could it be? The body inside the burial cloth started to writhe. Hastily unwrapping the cloth, the mourners found the child frantically kicking and crying. It’s a good thing the boy sneezed that day at his funeral, as the world is a much happier place because he survived. His name is Julius Achon, and he would grow up to become an Olympic athlete and, perhaps more important, a world-class humanitarian.

Julius was born on December 12, 1976, in Awake, a village that had no electricity or running water. “Life in Uganda is very tough,” says Julius, who spent his childhood sleeping between eight brothers and sisters on the floor of a one-room hut. People in the village drink water from the same well as cows and pigs and eat just one meal a day, two if they’re lucky, he explains. Julius grew up during a period when a government opposition group known as the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) began its campaign of terror in northern Uganda. At age 12, Julius was kidnapped by the LRA and forced to become a child soldier, but his spirit would not be broken. Three months later, he escaped from the rebel camp and, running much of the way, he returned to his village some 100 miles away.

Upon returning home, Julius began to run competitively. Running made him feel free, and running was his great gift. He ran barefoot to his first major track meet in the city of Lira, some 42 miles away from his village. Hours after arriving, Julius was racing—and winning—the 800 meters, the 1,500 meters, and the 3,000 meters (Kahn, 2012, January). From that point on, it was one success after another: a stunning victory at the national championships, a track scholarship at a prestigious high school in the capital city of Kampala, a gold medal at the World Junior Championships, a college scholarship from George Mason University in the United States, a collegiate record in 1996, and participation in the 1996 and 2000 Olympics (Kahn, 2012, January).

As awe-inspiring as these accomplishments may be, the greatest achievement in Julius Achon’s life was yet to come, and it had little to do with running. In 2003, while training back home in Uganda, he came upon a bus station in Lira. “I stopped, and then I saw children lying under the bus,” Julius says. They had been sleeping there for warmth. One of them stood up and started to beg for money—a 13- or 14-year-old girl clad in a tattered skirt and torn blouse. Then more children emerged, 11 of them in all, some teenagers and others as young as 3. They were terribly thin and dirty, and the little ones wore nothing more than long T-shirts and underwear.

“Where are your parents?” Julius remembers asking. One of the children said their parents had been shot and killed. “Can I walk you to my home, you know, to go eat?” Julius asked. The children eagerly agreed and followed him home for a meal of rice, beans, and porridge. What happened next may seem unbelievable, but Julius and his family are extraordinary people. Julius asked his father to shelter the 11 orphans, provided that he, Julius, would send money home to cover their living expenses. Julius had been running with a professional team in Portugal, making about $5,000 a year, not even enough to cover his own expenses. His parents already had six people living in their one-room home. How did his father respond?

“Ah, it’s no problem,” said Julius’s father. And just like that, Julius and his family adopted 11 children.

Power of Others

Throughout the years Julius was trotting the globe and winning medals, he never forgot about Uganda. He remembered the people back home with empty stomachs and no access to lifesaving medicine, living in constant fear of the LRA. Julius was raised in a family that had always reached out to neighbors in need. “You will get help from other people when you do good,” his parents used to say. Julius also felt blessed by all the support people outside the family had given him. “I feel I was so loved [by] others,” says Julius, referring to the mentors and coaches who had provided him with places to stay, clothes to wear, and family away from home.

So when Julius encountered those 11 orphans lying under the bus, he didn’t think twice about coming to their rescue. His decision to bring them into his life probably had something to do with the positive interactions he had experienced with people in his past.

Social Influence

LO 4 Describe social influence and recognize the factors associated with persuasion.

Rarely a day goes by that we do not come into contact with other human beings. This contact may be up close and personal, in a family or a tight-knit work group. Other times it’s more superficial, like the “Hello, how are you?” type of exchange you might have with a cashier at the store. Sometimes the interaction is so superficial that you never see the person face to face, like the online banker who helps you figure out why you were charged that mysterious fee. All of these interactions impact you in ways you may not realize. Psychologists refer to this as social influence—the way a person is affected by another person (or people) as apparent in behaviors, emotions, and cognition. Social influence can be glaringly obvious or barely noticeable, explicit or unspoken, strong or weak. We begin our discussion with a powerful, yet often overlooked, form of social influence: expectations.

Expectations

Think back to your days in elementary school. What kind of student were you—an overachiever, a kid who struggled, or perhaps the class clown? The answer to this question may depend somewhat on the way your teachers perceived you. In a classic study, Rosenthal and Jacobson (1966, 1968) administered a nonverbal intelligence test to students in a San Francisco elementary school. Then all the teachers were provided with a list of students who were likely to “show surprising gains in intellectual competence” during the next year (Rosenthal, 2002a. This prediction, they were told, was based on an intelligence test. But this was not true; the “intellectually competent” students were actually normal students who had been selected at random (a good example of how deception is used in social psychology). About 8 months later, the students were given a second intelligence test. Children whom the teachers expected to “show surprising gains” achieved greater increases in their test scores than their peers. Mind you, the only difference between these two groups was in teacher expectations and their resulting behaviors. The students who were expected to be superior actually became superior. Why do you think this happened?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 12, we discussed how poverty and its associated stressors can have a lasting impact on the development of the brain and subsequent cognitive abilities. Some factors that influence children’s brain development include nutrition, toxins, and abuse. Here, we see that the expectations of others can impact cognitive functioning as well.

As we discussed earlier, expectations can have a powerful impact on behaviors. Here, we have a case in which teachers’ expectations (based on false information) seemed to transform students’ aptitudes and facilitate substantial gains. Let’s consider the types of teacher behaviors that could explain this effect. The teachers may have inadvertently communicated expectations by demonstrating “warmer socioemotional” attitudes toward the “surprising gain” students; they may have provided them with more material and opportunities to respond to high expectations; and they may have given them more complex and personalized feedback (Rosenthal, 2002, 2003). From the student’s perspective, teacher behaviors can create a desire to work hard, or they can result in a decline in interest and confidence (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011).

Since this classic study was conducted approximately 50 years ago, researchers have studied expectations in a variety of classroom settings. Their results demonstrate that teacher expectations do not have the same effect or degree of impact on all students (Jussim & Harber, 2005). They appear to have greater influence on younger students (first and second graders) and children of lower socioeconomic status (Sorhagen, 2013).

Expectations are powerful, but they are just one form of social influence. Let’s return to the story of Julius for an example of a more targeted form of social influence.

Persuasion and Compliance

When Julius asked his father to shelter and feed the 11 orphans, he was using a form of social influence called persuasion. Persuasion means intentionally trying to make people change their attitudes and beliefs, which may (or may not) lead to changes in their behaviors. The person doing the persuading does not necessarily have control over those he seeks to persuade. Julius could not force his father to feel sympathy for the orphans. His father made a choice.

The important elements of persuasion were first described by Carl Hovland, a social psychologist who studied the morale of soldiers fighting in World War II. According to Hovland, three factors determine persuasive power: the source, the message, and the audience (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953).

The Source

The credibility of the person or organization sending a message is critical, and credibility can be dependent on perceived expertise and trustworthiness (Hovland & Weiss, 1951). Let’s look at an example. Suppose you are searching for information about the risks associated with vaccines—whom do you trust to furnish reliable information? In one study, German adults deemed vaccine information provided by government agencies to be more credible than that supplied by pharmaceutical companies (Betsch & Sachse, 2013). Of course, this assessment of government credibility depends on whether citizens consider the government trustworthy.

Persuasive ability also hinges on the attractiveness of the source, with more attractive people tending to be more persuasive (Bekk & Spörrle, 2010). But it’s not just about who is sending the message. The content of the message also determines persuasive power.

The Message

What particular features of a message determine its power? One important factor is the degree to which the message is logical and to the point (Chaiken & Eagly, 1976). Fear-inducing information can increase persuasion, but it can also backfire. Imagine someone uses this message to encourage teeth-flossing: “If you don’t floss daily, you can end up with infected gums, and that infection can spread to your eyes and create total blindness!” If the audience is overly frightened by a message (imagine small children being told to floss … or else!), the tension they feel may actually interfere with their ability to process the message (Janis & Feshbach, 1953). If fear is used for the purpose of persuasion, those being persuaded must be provided with information about how to cope with any negative outcomes (Leventhal, Watts, & Pagano, 1967). Being as “gruesome as possible” is not effective; a better approach is to provide clear information about the negative consequences of not being persuaded (de Hoog, Stroebe, & de Wit, 2007).

Julius: How did you persuade your father to take in the 11 orphans?

The Audience

Finally, we turn to the audience. Who is being persuaded, and which of their characteristics matter? One factor is age. For example, middle-age adults (40 to 60 years old) are unlikely to be persuaded to change their attitudes, whereas children are relatively susceptible (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). Another key factor is emotional state; when people are happy and well fed, they are more likely to be persuaded (Aronson, 2012; Janis, Kaye, & Kirschner, 1965). Mental focus is also key: If your mind is somewhere else, you are less likely to be affected by message content (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986).

Elaboration Likelihood Model

The elaboration likelihood model proposes that persuasion hinges on the way people think about an argument, and it can occur via one of two pathways. With the central route to persuasion, the focus is on the content of the message, and thinking critically about it. With the peripheral route, the focus is not on the content but on “extrames-sage factors” such as the credibility or attractiveness of the source (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Little critical thinking is involved, and the commitment to the outcome is low. But how do we know which route the message will take? If the person receiving the message is knowledgeable and invested in its outcome, the central route to persuasion is used. If the person is distracted, lacks knowledge about the topic, or does not feel invested in the outcome, the peripheral route is typically taken (O’Keefe, 2008).

Immediately following the tragedy of the Newtown massacre in late 2012, there was an upsurge in calls for tighter gun control in the United States. Someone with strong feelings about gun control (either for or against it) would likely take advantage of central processing when trying to develop a persuasive argument. Some politicians, for example, tried to persuade others by supplying data about the number of gun-related deaths worldwide: “The United States, which has, per capita, more firearms and particularly more handguns than … [22 other ‘populous, high-income’] countries, as well as the most permissive gun control laws, also has a disproportionate number of firearm deaths—firearm homicides, firearm suicides, and firearm accidents” (Richardson & Hemenway, 2011, p. 243). Such a message would be more persuasive to a person who is knowledgeable and invested in the issue, and thus uses the central processing route. Someone who is unfamiliar with and/or indifferent about gun-control policy would probably be more persuaded by the credibility of the source, appearance of the speaker, and so on.

The take-home message: If you want to persuade as many people as possible, make sure your arguments are logical and you present yourself as credible and attractive. That way you will be able to take advantage of both routes when making your case to an audience.

Compliance

LO 5 Define compliance and explain some of the techniques used to gain it.

Being persuaded to change our attitudes about vaccinations or our opinions about broccoli is an act of free will. The results of persuasion are internal and related to a change in attitude (Key, Edlund, Sagarin, & Bizer, 2009). Compliance, on the other hand, occurs when someone voluntarily changes her behavior at the request or direction of another person or group, who in general does not have any true authority over her. Compliance is evident in changes to “overt behavior” (Key et al., 2009). For example, if you want to get someone to help clean up after a party, you would try to get him to comply with your request, perhaps through some mild form of guilt (Remember the last party we had when I helped you?).

Surprisingly, compliance often occurs outside of our awareness. Think of an everyday situation in which you mindlessly comply with another person’s request. You’re waiting in line at the copy machine, and someone asks if he can cut in front of you. Do you allow it? Your response may depend on the wording of the request. Researchers studying this very scenario—a person asking another person to cut in line—have found that compliance is much more likely to result when the request is accompanied by a reason. Saying, “Excuse me, I have 5 pages. May I use the [copy] machine?” will not work as well as “Excuse me, I have 5 pages. May I use the [copy] machine, because I am in a rush?” People are more likely to comply with a request that includes a “because” phrase, even if the reasoning is not logical. For example, stating that you need to use the copy machine “because I am in a rush” achieves about the same compliance as “because I have to make copies” (Langer, Blank, & Chanowitz, 1978). Kind of scary, right?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 4, we discussed the automatic cognitive activity that guides some behaviors. These behaviors appear to occur without our intent or awareness. Compliance can be driven by automatic processes.

Well … Okay

The potential mindlessness associated with compliance should encourage you to reflect on when else you might automatically comply (Fennis & Janssen, 2010). For example, salespeople or marketing experts routinely use a variety of techniques to get consumers to comply with their requests. One common method is the foot-in-the-door technique, which occurs when someone asks for a small request, followed by a larger request (Freedman & Fraser, 1966). If a college club is trying to persuade students to help perform a large service project (such as raising money for packages to be sent to soldiers overseas), its members might first stop students in the hallway and ask them if they could help with a smaller task (labeling a couple of donated boxes lying close by). If a student responds positively to this small request, then the club members might make a bigger request (to sponsor packages), with the expectation that the student will comply with the second request on the grounds of having said yes to the first request. Why would this technique work?

The reasoning is that if you have already said yes to a small request, chances are you will agree to a bigger request to remain consistent in your involvement. Your prior participation leads you to believe you are the type of person who gets involved; in other words, your attitude has shifted (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Freedman & Fraser, 1966). So why is such a strategy called foot-in-the-door? In the past, salespeople went door-to-door trying to sell their goods and services, and they would often be successful if they could physically get a “foot in the door,” thereby keeping it open, which allowed them to continue with their sales pitch.

Another method for gaining compliance is the door-in-the-face technique, which involves making a large request first, and then a smaller request. With this technique, the expectation is that the person will not go along with the large request, but because the smaller request may seem so minor by comparison, the person will comply with it. There are numerous reasons people comply under these circumstances, but the main reason seems to be one of reciprocal concessions. If the solicitor (the person trying to obtain something) is willing to give up something (the large request), the person being solicited tends to feel that he too should give in and satisfy the smaller request (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). Think back to the college club that really does need help addressing boxes. Its members might stop students and ask them to make a contribution to sponsor a package, but if a student says no to this request, the club representative may then say, “Okay, but can you at least help address a few boxes for us?” Chances are good students will comply with this request because it seems minor relative to the first one.

Let’s review these concepts using Julius as an example. After meeting the 11 orphans, Julius brought them home and asked his parents to provide them with a meal. Once his parents complied with this initial request, Julius made a much larger request—he asked them to shelter the children indefinitely. This is an example of the foot-in-the-door technique because Julius first made a modest request (“Will you feed these children?”) and then followed up with a larger one (“Will you shelter these children?”). Had these requests been flip-flopped, that is, had Julius only wanted to get the children a meal but first asked his parents if the children could move in, we would call it the door-in-the-face technique.

Compliance generally occurs in response to specific requests or instructions: Will you pick up the kids after school? Can you chop these onions? Please collect your sweaty socks from the bathroom floor! But social influence needn’t be explicit. Sometimes we adapt our behaviors and beliefs simply to fit in with the crowd.

Conformity

Julius: Is it difficult for you to return home to Uganda?

When Julius came to the United States on a college scholarship in 1995, he was struck by some of the cultural differences he observed between the United States and Uganda—the way people dressed, for example. Women wore considerably less clothing, and men could be seen wearing jeans halfway down their posteriors (the “sagging” pants phenomenon). There were other differences, like the way people addressed authority figures. In Africa, explains Julius, students speak to their teachers with a certain kind of respect, using a low voice and standing still with their legs close together. Americans tend to use a more casual tone, he notes; they stand with their legs farther apart and shift around during conversation.

Throughout the years Julius has been abroad, he has never stopped acting like a Ugandan. “I am not changed,” says Julius, who has worked and lived in the United States for the last decade. Before going out in the evening, Julius tucks in his shirt, checks his hair, and makes sure his clothes are ironed—and he never wears sagging pants. You might say Julius has refused to conform to certain aspects of American culture—and resisting conformity is not always easy to do.

Following The Crowd

LO 6 Evaluate conformity and identify the factors that influence the likelihood of someone conforming.

Have you ever found yourself turning to look in the same direction as other people who are staring at something, just because you see them doing so? During the Waldo Canyon Fires in Colorado Springs in the summer of 2012, a day did not pass without people pointing to the mountain range. It was next to impossible to avoid looking in the direction they were pointing, and not just because of the smoke coming from the mountains. We seem to have a commanding urge to do what others are doing, even if it means changing our normal behavior. This tendency to modify our behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions to match those of others is known as conformity. Sometimes we conform to the norms or standards of the social environment, such as the group to which we are connected. Unlike compliance, which occurs in response to an explicit and direct request, conformity is generally unspoken. We often conform because we feel compelled to fit in and belong.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we described Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which includes the need to belong. If physiological and safety needs are met, an individual will be motivated by the need for love and belongingness. Here we suggest that this need drives us to conform and fit in.

It is important to note that conformity is not always a bad thing. We rely on conformity in many cases to ensure the smooth running of day-to-day activities involving groups of people. Think of what a third-grade classroom would be like if it weren’t for the human urge to conform to what others are doing. Imagine checking out at Target if none of the customers adhered to common social rules.

try this

The next time you are outside in a fairly crowded area, look up and keep your eyes toward the sky. You will find that some people change their gazes to match yours, even though there is no other indication that something is happening above.

Studying Conformity

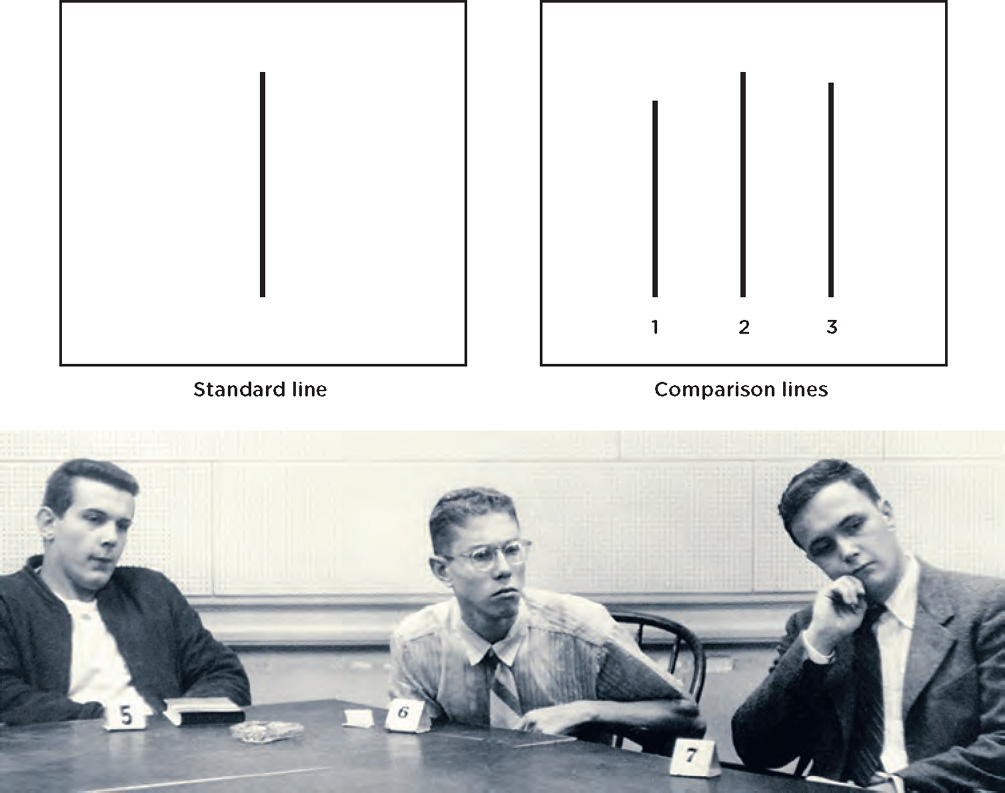

Social psychologists have studied conformity in a variety of settings, including American colleges. In a classic experiment by Solomon Asch (1955), college-student participants were asked to sit at a table with six other people, all of whom were confederates working for the researcher. The participants were told to look at two cards, one with one vertical line on it, the standard line, and the other card with three vertical lines, each of different lengths but marked 1, 2, and 3 (Figure 15.3). The group seated at the table was instructed to look at the two cards and then announce, one at a time going around the table, which of the three lines was closest in length to the standard line, thus making a “visual judgment.” The first two rounds of this task went smoothly, with everybody in agreement about which of the three lines matched the standard. But then, in the third round, the first five confederates at the table offered what was clearly the wrong answer, one after the other (prior to the experiment, the researchers had given them instructions about which line to choose in each trial).

Would the real participant (the sixth person to answer) follow suit and conform to the wrong answer, or would he stand his ground and report the correct answer? In roughly 37% of these trials, participants went along with the group and provided the incorrect answer. Furthermore, 76% of the participants conformed to the incorrect answers of the confederates at least once (Asch, 1955, 1956). When members of the control group made the same judgments alone in a room, they were correct 99% of the time, confirming that the differences between the standard line and the comparison lines were substantial, and generally not difficult to assess. This type of study was later replicated in a variety of cultures, with mostly similar results (Bond & Smith, 1996).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we explained that a control group in an experiment is not exposed to the treatment variable. In this case, the control group is not exposed to the confederates making incorrect answers.

Why Conform?

Clearly, people do not always conform to the behavior of others, but what factors come into play when they do? There are three major reasons for conformity. Most of us want the approval of others, to be liked and accepted. This desire influences our behavior and is known as normative social influence. Just think back to middle school—do you remember feeling pressure to be like some of your classmates or friends? This might have been due to a normative social influence to conform, so that you could fit in. A second reason we conform is so we might behave correctly; we look to others for confirmation when we are uncertain about something, and then do as they do. This is known as informational social influence. Perhaps you have a friend who is particularly well read in politics but you are not, or who is extremely knowledgeable about psychology. In both cases, your tendency is to defer to their expert knowledge. Third, we sometimes conform to others because they belong to a certain reference group we respect, admire, or long to join.

Certain conditions increase the likelihood of conforming (Aronson, 2012; Asch, 1955):

- The group includes at least three other people who are unanimous.

- You have to report your decision in front of others and give your reasons.

- The task seems difficult to you.

- You are unsure of your ability to perform the task.

Certain conditions decrease the likelihood of conforming:

- At least one other person is going against the group with you (Asch, 1955).

- Group members come from individualist, or “me-centered” cultures, meaning they are less likely to conform than those from collectivistic, or more community-centered cultures (Bond & Smith, 1996).

When you conform, no one is specifically telling you to do so. But this is not the case with all types of social influence (TABLE 15.1). Let’s take a trip to the darker side and explore the frightening phenomenon of obedience.

| Concept | Definition | Example |

| Persuasion | Intentionally trying to make people change their attitudes and beliefs, which may or may not lead to their behavior changing | Buy our product because it is the best on the market. |

| Compliance | Voluntarily changing behavior at the request or direction of another person or group, who in general does not have any authority over you | Remove your shoes before you walk into the house because you have been asked. |

| Conformity | Urge to modify our behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions to match those of others | Remove your shoes before you walk into the house because everyone else who has entered did the same. |

| Obedience | Changing our behavior because we have been ordered to do so by someone in authority | Follow the detour sign. |

| Whether or not you realize it, other people constantly shape your thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Above are some of the key elements of social influence. | ||

BOY SOLDIERS

During Uganda’s two-decade civil war, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) is said to have kidnapped some 66,000 youths. Scholars have estimated that 20% of male victims did not make it home (Annan, Blattman, & Horton, 2006). Julius came dangerously close to losing his life during a village raid that he and other child soldiers were forced to conduct. His boss ordered him to shoot a man who refused to hand over a chicken, but Julius would not pull the trigger. Had the boss not come from Julius’s home village, the punishment probably would have been death. Instead, Julius received a caning that rendered him incapable of sitting for a week.

During Uganda’s two-decade civil war, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) is said to have kidnapped some 66,000 youths. Scholars have estimated that 20% of male victims did not make it home (Annan, Blattman, & Horton, 2006). Julius came dangerously close to losing his life during a village raid that he and other child soldiers were forced to conduct. His boss ordered him to shoot a man who refused to hand over a chicken, but Julius would not pull the trigger. Had the boss not come from Julius’s home village, the punishment probably would have been death. Instead, Julius received a caning that rendered him incapable of sitting for a week.

While a captive of the LRA, Julius witnessed other boy soldiers assaulting innocent people and stealing property. Sometimes at the end of the day, they would laugh or brag about how many people they had beaten or killed. But these were just “normal” boys from the villages, boys who never would have behaved this way under regular circumstances. And some showed clear signs of regret. Julius remembers seeing other child soldiers cry alone at night after returning to the camp when there was time to reflect on what they had done.

How do you explain this tragedy? What drives an ordinary child to commit senseless violence? A psychologist might tell you it has something to do with obedience.

Obedience

LO 7 Describe obedience and explain how Stanley Milgram studied it.

One of the most disconcerting results of social influence is obedience, which occurs when we change our behavior, or act in a way we might not normally act, because we have been ordered to do so by an authority figure. In these situations, an imbalance of power exists, and the person with more power (for example, a teacher, police officer, doctor, or boss) generally has an advantage over someone with less power (who is more likely to be obedient out of respect, fear, or concern). In some cases, the person in charge demands obedience for the good of those less powerful (a father demanding obedience from a child running wildly through a crowded store). Other times, the person wielding power demands obedience for his own benefit (an adult who perpetrates sexual abuses against innocent children).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 14, we introduced the concept of transference, a reaction some clients have to their therapists. A client demonstrating transference responds to the therapist as if dealing with a parent, or other important caregiver from childhood; this may include behaving more childlike and obedient.

This Will Shock You: Milgram’s Study

Back in the 1960s, psychologist Stanley Milgram was interested in determining the extent to which obedience can lead to behaviors that most people would consider unethical. Milgram (1963, 1974) conducted a series of studies examining how far people would go, particularly in terms of punishing others, when urged to do so by an authority figure. Participants were told the study was about memory and learning (another example of research deception). The sample included teachers, salespeople, post office workers, engineers, and laborers, representing a wide range of educational backgrounds, from elementary school dropouts to people with graduate degrees.

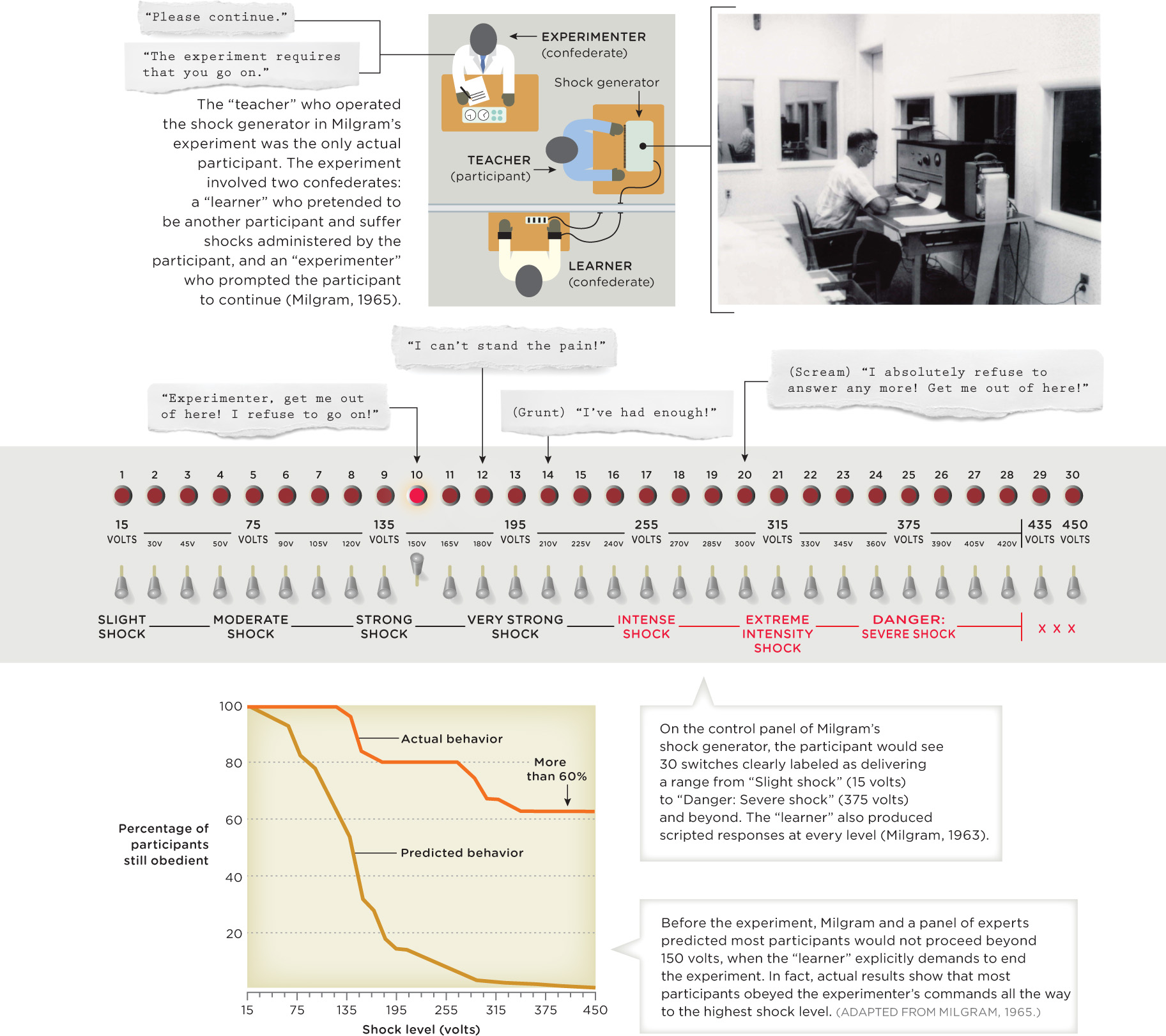

Upon arriving at the Yale University laboratory, participants were informed they would be using punishment as part of a learning experiment. They were then asked to draw a slip of paper from a hat; the slip told them they had been randomly assigned the teacher role, although the truth was that a confederate always played the role of the learner (the hat contained two slips that both read “teacher”). To start, the participant was asked to sit in the learner’s chair, so that he could experience a 45-volt shock, just to know what the learner might be feeling. The teacher was told that the goal was for the learner to memorize a set of paired words. The teacher sat at a table that held a control panel for the generation of shocks. The panel went from 15 volts to 450 volts, and as you can see in Infographic 15.2, this range of voltage was labeled from “slight shock” to “XXX.” The teacher was then told he was to administer a shock each time the learner made a mistake, and that the shock was to increase by 15 volts for every mistake. The learner was located in a separate room, arms strapped to a table and electrodes attached to his wrists; the electrodes were reportedly attached to a shock generator.

As you might have concluded, the learner (the confederate) was not really going to receive any true shocks, but had a script of responses he was to make as the experiment continued. The learner’s behaviors, including the mistakes he made and his responses to the increasing shock levels (including mild complaints, screaming, references to his heart condition, pleas for the experiment to stop, and total silence as if he were unconscious or even dead), were identical for all participants. A researcher in a white lab coat (also a confederate with scripted responses) always remained in the room with the teacher, and he was insistent that the experiment proceed if the teacher began to question going any further given the learner’s responses (such as “Experimenter, get me out of here…. I refuse to go on” or “I can’t stand the pain”; Milgram, 1965, p. 62). The researcher would say to the teacher, “Please continue” and “You have no other choice, you must go on” (Milgram, 1963, p. 374).

How many teachers do you think obeyed the researcher and proceeded with the experiment in spite of the learner’s desperate pleas? Before the experiment, Milgram asked a variety of people (including psychiatrists and students) to predict how many teachers would be obedient and obey the researcher. Many believed that the participants would refuse to continue at some point in the experiment. Most of the psychiatrists, for example, predicted that only 0.125% of participants would continue to the highest voltage (Milgram, 1965). They also guessed that the majority of the participants would quit the experiment when the learner began his protests.

Here’s what actually happened: 65% of participants continued to the highest voltage level (to the point Milgram said there was “a whopping discrepancy” between predictions and outcome. Most of these participants were obviously not comfortable with what they were doing (stuttering, sweating, trembling), yet they continued. Even those who eventually refused to proceed went much farther than anyone had predicted (even Milgram himself)—they all used shocks up to at least 300 volts (labeled as “Intense Shock”) (Milgram, 1963, 1964; Infographic 15.2).

We should emphasize that participants were not necessarily comfortable with their role as teachers, even when they continued with the experiment. One observer of the study reported the following:

I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse. He constantly pulled on his earlobe, and twisted his hands. At one point he pushed his fist into his forehead and muttered: “Oh God, let’s stop it.” And yet he continued to respond to every word of the experimenter, and obeyed to the end. (Milgram, 1963, p. 377)

Replicating Milgram

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we reported that professional organizations have specific guidelines to ensure ethical treatment of research participants. They include doing no harm, safeguarding welfare, and respecting human dignity. An Institutional Review Board also ensures the well-being of participants.

This type of research has been replicated in the United States and in other countries, and the findings have remained fairly consistent, with 61–66% of participants continuing to the highest level of shock (Aronson, 2012; Blass, 1999). Not surprisingly, the criticisms of Milgram’s studies were strong. Many were concerned that this research went too far with its deception (it would certainly not receive approval from an Institutional Review Board today), and some wondered if the participants were harmed by knowing that they theoretically could have killed someone with their choices during the study. Milgram (1964) spent time with the participants following the study, and reported that 84% claimed they were “glad” they had participated, whereas only 1.3% reported they were “sorry” to have been involved. The participants were seen for psychiatric evaluations a year later, and reports indicate that none of them “show[ed] signs of having been harmed by his experiences” (Milgram, 1964, p. 850).

INFOGRAPHIC 15.2: Milgram’s Shocking Obedience Study

Stanley Milgram’s study on obedience and authority was one of the most ground-breaking and surprising experiments in all of social psychology. Milgram wanted to test the extent to which we will follow the orders of an authority figure. Would we follow orders to hurt someone else, even when that person was begging us to stop? Milgram’s experiment also raises the ethical issues of deception and informed consent. Participants had to actually think they were shocking another person for the experiment to work. Creating this deception involved the use of confederates (people secretly working for the researchers) whose behaviors and spoken responses were carefully scripted. Milgram found high levels of obedience in his participants—much higher than he and others had predicted at the beginning of the study.

Milgram and others have followed up on the original study, to determine if there were specific factors or characteristics that made it more likely someone would be obedient in this type of scenario (Blass, 1991; Burger, 2009; Milgram, 1965). Burger (2009) conducted a partial replication of Milgram’s original research, with the exception of stopping the experiment at the 150-volt level. In Burger’s study, 70% of the participants went to the highest level of voltage (150 volts), which is a slightly lower percentage than continued to the 150-volt level in the original study.

Several key factors determined whether participants were obedient in these studies: (1) the legitimacy of the authority figure (the more legitimate, the more obedience demonstrated by participants); (2) the closeness of the authority figure (the closer the experimenter was to participants, the higher their level of obedience); (3) the closeness of the learner (the closer the learner, the less obedient the participant); and (4) the presence of other teachers (if another confederate was acting as an obedient teacher, the participant was more likely to obey as well).

Milgram’s initial motivation for studying obedience came from learning about the horrific events of World War II and the Holocaust, which “could only have been carried out on a massive scale if a very large number of people obeyed orders” (Milgram, 1974, p. 1). And he found the same types of responses in his experiments on obedience. One ray of hope did shine through in his later experiments, and that was how participants responded when they saw others refuse to obey. In one follow-up experiment, two more confederates were included in the study as additional teachers. If these confederates showed signs of refusing to obey the authority figure, the research participant was far less likely to cooperate. In fact, Milgram (1974) reported that in this type of setting, only 10% of the research participants were willing to carry on with the learning experiment. What this suggests is that one person can make a difference, and when someone stands up for what is right, others will follow that lead.

show what you know

Question 15.8

1. Match the following definitions with the terms:

- how a person is affected by another person

- intentionally trying to make people change their attitudes

- a person voluntarily changes behavior at the request of someone without authority

- someone asks for a small request, followed by a larger request

- the urge to modify behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs to match those of others

- _____ conformity

- _____ persuasion

- _____ compliance

- _____ foot-in-the-door technique

- _____ social influence

a. social influence; b. persuasion; c. compliance; d. foot-in-the-door technique; e. conformity

Question 15.9

2. __________ occurs when we change our behavior, or act in a way we might not normally, because we have been ordered to do so by an authority figure.

- Persuasion

- Compliance

- Conformity

- Obedience

d. Obedience

Question 15.10

3. Asch’s experiments with conformity show how difficult it is to resist the urge to conform to the behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions of others. At the same time, many of his participants did not cave in to so-called peer pressure. Can you think of an everyday example in which somebody successfully resisted the urge to conform?

Answers will vary. Examples may include resisting the urge to eat dessert when others at the table are doing so, saying no to a cigarette when others offer one, and so forth.