15.4 Groups and Relationships

Thus far, the primary focus of this chapter has been individuals in social situations. We learned, for example, how individuals process information about other people (social cognition) and how behavior is shaped by social interactions (social influence). But human beings do not exist solely as isolated units. When striving toward a common goal, we often come together in groups, and these groups have their own fascinating social dynamics.

LET’S DO THIS TOGETHER

The most important competition of Julius Achon’s career was probably the 1994 World Junior Championships in Portugal. Julius was 17 at the time, and he represented Uganda in the 1,500 meters. It was his first time flying on an airplane, wearing running shoes, and racing on a rubber track. No one expected an unknown boy from Uganda to win, but Julius surprised everyone, including himself. Crossing the finish line strides ahead of the others, he almost looked uncertain as he raised his arms in celebration.

The most important competition of Julius Achon’s career was probably the 1994 World Junior Championships in Portugal. Julius was 17 at the time, and he represented Uganda in the 1,500 meters. It was his first time flying on an airplane, wearing running shoes, and racing on a rubber track. No one expected an unknown boy from Uganda to win, but Julius surprised everyone, including himself. Crossing the finish line strides ahead of the others, he almost looked uncertain as he raised his arms in celebration.

Julius ran the 1,500 meters (the equivalent of 0.93 miles) in approximately 3 minutes and 40 seconds. Do you suppose he would have run this fast if he had been alone? Research suggests the answer is no (Worringham & Messick, 1983). In some situations, people perform better in the presence of others. This is particularly true when the task at hand is uncomplicated (running) and group members are well prepared (runners may spend months training for races). Thus, social facilitation can improve personal performance when the task is fairly straightforward and a person is adequately prepared.

Sometimes other “people” don’t have to be present and watching for social facilitation to work. For example, when faced with competitive avatars (graphical representations of people) while riding a stationary “cybercycle,” more competitive elderly adults tend to put forth a greater effort than their less competitive counterparts (Anderson-Hanley, Snyder, Nimon, & Arciero, 2011).

When Two Heads Are Not Better Than One

Being around other people does not always provide a performance boost, however. Learning or performing difficult tasks may actually be harder in the presence of others (Aiello & Douthitt, 2001), and group members may not put forth their best effort. When individual contributions to the group aren’t easy to ascertain, social loafing may occur (Latané, Williams, & Harkins, 1979). Social loafing is the tendency for people to make less than their best effort when individual contributions are too complicated to measure. Many students will shy away from working in groups because of the negative experiences they have had with other group members’ social loafing. Want some advice on how to reduce social loafing? Even if an instructor doesn’t require it, you should try to get other students in your group to designate and take responsibility for specific tasks, have group members submit their part of the work to the group before the assignment is due, and specify their contributions to the end product (Jones, 2013; Maiden & Perry, 2011).

Social loafing often goes hand-in-hand with diffusion of responsibility, or the sharing of duties and responsibilities among all group members. Diffusion of responsibility can lead to feelings of decreased accountability and motivation. If we suspect other group members are slacking, we tend to follow suit in order to keep things equal.

across the WORLD

Slackers of the West

It turns out that social loafing is more likely to occur in societies where people place a high premium on individuality and autonomy. These individualistic societies include the United States, Western Europe, and other parts of the Western world. In the collectivistic cultures of China and other parts of East Asia, people tend to prioritize community over the individual, and social loafing is less likely to occur. Group members from these more community-oriented societies actually show evidence of working harder (Kerr & Tindale, 2004; Smrt & Karau, 2011). And unlike their individualistic counterparts, they are less interested in outshining their comrades. Preserving group harmony is more important (Tsaw, Murphy, & Detgen, 2011).

It turns out that social loafing is more likely to occur in societies where people place a high premium on individuality and autonomy. These individualistic societies include the United States, Western Europe, and other parts of the Western world. In the collectivistic cultures of China and other parts of East Asia, people tend to prioritize community over the individual, and social loafing is less likely to occur. Group members from these more community-oriented societies actually show evidence of working harder (Kerr & Tindale, 2004; Smrt & Karau, 2011). And unlike their individualistic counterparts, they are less interested in outshining their comrades. Preserving group harmony is more important (Tsaw, Murphy, & Detgen, 2011).

IF YOU ARE TRAVELING TO EAST ASIA, SHOULD YOU LEAVE YOUR EGO AT HOME?

Nothing in psychology is ever that simple, however. Social loafing may be less common in collectivist cultures, but it certainly happens (Hong, Wyer, & Fong, 2008). And within every “individualistic” or “collectivistic” society are individuals who do not behave according to these generalities. We should also point out that many group tasks require both individual and shared efforts; in these situations, a combination of individualism and collectivism may lead to more successful outcomes (Wagner, Humphrey, Meyer, & Hollenbeck, 2011).

Deindividuation

In the last section, we discussed how obedience played a role in the senseless violence carried out by boy soldiers in Uganda. We suspect that the actions of these children also had something to do with deindividuation. People in groups sometimes feel a diminished sense of personal responsibility, inhibition, or adherence to social norms. This state of deindividuation can occur when group members are not treated as individuals, and thus begin to exhibit a “lack of self-awareness” (Diener, 1979). As members of a group, the boy soldiers may have felt a loss of personal identity, social responsibility, and ability to discriminate right from wrong.

Research suggests that children are indeed vulnerable to deindividuation. In a classic study of trick-or-treaters, Ed Diener, a professor and researcher at the University of Illinois, and his colleagues set up a study in 27 homes throughout Seattle, Washington. Children arriving at these houses to trick-or-treat were ushered in by a woman (who was a confederate, of course). She told them they could take one piece of candy, which was on a table in a bowl. Coincidentally, next to the bowl of candy (about 2 feet away) was a second bowl full of small coins (pennies and nickels). The woman then excused herself, saying she had to get back to work in another room. What the children didn’t know was that another experimenter was observing their behavior through a peep hole, tallying up the amount of candy and/or money they took. The other variable being recorded was the number of children and adults in the hallway; remember, the experimenters never knew how many people would show up when the doorbell rang!

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed a type of descriptive research that involves studying participants in their natural environments. Naturalistic observation requires that the researcher not disturb the participants or their environment. Would Diener’s study be considered naturalistic observation?

The findings were fascinating. If a parent was present, the children were well behaved (only 8% took more than their allotted one piece of candy). But with no adult present, their behavior changed dramatically. Of the children who came to the door alone and anonymous (the confederate did not ask for names or other identifying information), 21% took more than they should have. By comparison, 80% of the children who were in a group and anonymous took extra candy and/or money. The researchers suggested that the condition of being in a group combined with anonymity created a sense of deindividuation (Diener et al., 1976). Are you wondering how much money and candy the kids took? It seems that the children who took more than their fair share of candy grabbed as much as their hands could hold (between 1.6 and 2.3 extra candy bars, on average). As for the money, around 14% of the children stole coins (and ignored the candy), while nearly 21% took money and more than one piece of candy.

CONNECTIONS

What else motivated the children who were alone? In Chapter 9, we discussed various sources of motivation, ranging from instincts to the need for power. Which of these sources of motivation might help explain why some children took more than their fair share of candy when they thought no one was watching?

We have shown how deindividuation occurs within groups of children, but what about adults? Perhaps you have heard about “Bedlam,” a football game between arch rival teams from the University of Oklahoma (OU) and Oklahoma State University (OSU). Most years, OU has won, but in 2011, OSU beat OU 44-10. This was the first time in the university’s history it captured a Big 12 championship, and the first time it had beaten OU in 9 years. With just a few seconds left, thousands of OSU fans stormed the field, tearing down the goal posts and injuring several people in the celebration. Although an announcement was made toward the end of the game, with the policy of staying off the field made very clear, fans ignored it and even laughed as they flooded the field, without regard for the safety of others. The fans’ poor decisions seemed to be a result of deindividuation. This type of behavior has been repeated in many settings and with many groups of people. Why can’t we learn to make better decisions when we find ourselves in groups? Perhaps it has something to do with our tendency to act in rash and extreme ways when surrounded by others.

Risky Shift

Imagine you have $250,000 to spend for your company. Will you spend more if you’re making decisions alone or working as part of a committee? Researcher James A. F. Stoner (1961, 1968) set out to find the answer to this question, and here’s what he discovered: When group members were asked to make a unanimous decision on how to spend the money, they were more likely to recommend uncertain and risky options than individuals working alone, a phenomenon known as the risky shift.

Group Polarization and Groupthink

As members of a group work together, their positions tend to become more extreme. If people who strongly support the legalization of marijuana are assembled in a group, their position will become increasingly pro-legalization over time. This phenomenon is known as group polarization, or the tendency for a group to take a more extreme position after deliberations and discussion (Myers & Lamm, 1976). As the members of the group listen to each other make arguments, their original positions become more entrenched. Thus, when people hear their opinions echoed by other members of the group, the conversation tends to become more extreme, as the new information tends to reinforce and strengthen the group members’ original positions. This raises the following question: Does group deliberation actually help? Perhaps not when the members are initially in agreement.

As a group becomes increasingly united, a very different group dynamic, or process, known as groupthink can occur. This is the tendency for group members to maintain cohesiveness and agreement in their decision making, failing to consider all possible alternatives and related viewpoints (Janis, 1972; Rose, 2011). Groupthink has received part of the blame for a variety of disasters, including the Challenger space shuttle explosion in 1986, the Mount Everest climbing tragedy in 1996, and the U.S. decision to invade Iraq in 2003 (Badie, 2010; Burnette, Pollack, & Forsyth, 2011).

As you can see, groupthink can have life-or-death consequences. So, too, can the bystander effect, another alarming phenomenon that occurs among people in groups.

THE BYSTANDER WHO REFUSED TO STAND BY

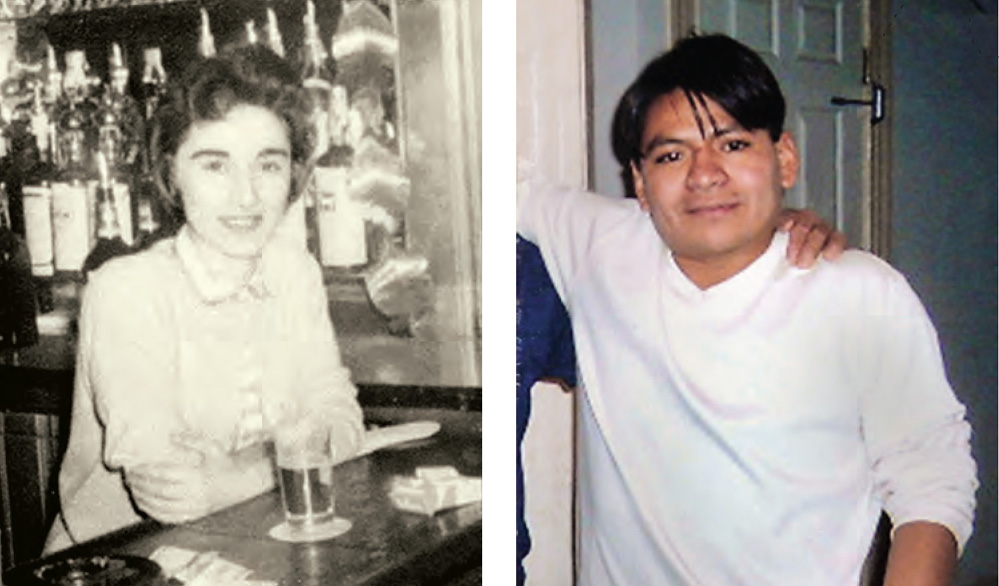

Before meeting Julius in 2003, the orphans spent their days begging for money and searching for food. Usually, they ate scraps that hotels had poured onto side roads for dogs and cats. Every morning it was the same routine: Wake up, split apart, and search for something to eat. No time for teamwork or group strategizing. But the orphans did help each other when possible, explains Samuel (“Sam”) Mugisha, one of the older kids in the original 11 (S. Maugisha, personal communication, March 9, 2012). At night, they kept each other warm coiled beneath the bus, and they shared food when there was enough to go around. The older children looked after the little ones, making sure they had something to eat. The orphans leaned on one another, but they didn’t get much assistance from the outside world.

Before meeting Julius in 2003, the orphans spent their days begging for money and searching for food. Usually, they ate scraps that hotels had poured onto side roads for dogs and cats. Every morning it was the same routine: Wake up, split apart, and search for something to eat. No time for teamwork or group strategizing. But the orphans did help each other when possible, explains Samuel (“Sam”) Mugisha, one of the older kids in the original 11 (S. Maugisha, personal communication, March 9, 2012). At night, they kept each other warm coiled beneath the bus, and they shared food when there was enough to go around. The older children looked after the little ones, making sure they had something to eat. The orphans leaned on one another, but they didn’t get much assistance from the outside world.

Day after day, they encountered hundreds of passersby. But of all those people, only three or four would typically offer food or money, nothing more—until a thin, muscular man clad in the most unusual outfit appeared. Wearing a sleeveless top (a runner’s singlet), short shorts, and fancy sneakers, Julius Achon looked different from any person the orphans had seen before. And he was, of course, different. This man would ultimately ensure the orphans had everything they needed for a chance at a better life—food, clothing, a place to sleep, an education, and a family.

The Bystander Effect

LO 8 Recognize the circumstances that influence the occurrence of the bystander effect.

Before meeting Julius, the orphans had been homeless for several months. Why didn’t anyone try to rescue them? “Everybody was fearing responsibility,” Julius says. In northern Uganda, many people cannot even afford to feed themselves, so they are reluctant to lend a helping hand.

But perhaps there was another factor at work, one that psychologists call the bystander effect. When a person is in trouble, bystanders have the tendency to assume (and perhaps wish) that someone else will help—and therefore they stand by and do nothing, partly a result of the diffusion of responsibility. This is particularly true when there are many other people present. Strange as it seems, we are more likely to aid a person in distress if no one else is present (Darley & Latané, 1968; Eagly & Crowley, 1986; Latané & Darley, 1968). So when people encountered the 11 orphans begging on the street, they probably assumed and hoped somebody else would take care of the problem. These children must belong to someone; their parents will come back for them.

Perhaps the most famous illustration of the bystander effect was the attack on Kitty Genovese. It was March 13, 1964, around 3:15 a.m., when Catherine “Kitty” Genovese arrived home from work in her Queens, New York, neighborhood. As she approached her apartment building, an attacker brutally stabbed her. Kitty screamed for help, but initial reports suggested that no one came to her rescue. The attacker ran away, and Kitty stumbled to her apartment building. But he soon returned, raping and stabbing her to death. The New York Times originally reported that 38 neighbors heard her cries for help, witnessed the attack, and did nothing to help. But the evidence suggests that the second attack occurred inside her building, where few people could have witnessed it (Manning, Levine, & Collins, 2007).

More recently, in April 2010, a homeless man (also in Queens) was left to die after several people walked by him and decided to do nothing. The man, Hugo Tale-Yax, had been trying to help a woman under assault, but the attacker stabbed him in the chest (Livingston, Doyle, & Mangan, 2010, April 25). As many as 25 people walked past Mr. Tale-Yax as he lay on the ground dying, and one even took a cell phone picture of him before walking away. Can you think of any reason why they wouldn’t help? Would you help someone in such a situation?

A recent review of the research suggests that things might not be as “bleak” as these events suggest. In extremely dangerous situations, bystanders are actually more likely to help even if there is more than one person watching. More dangerous situations are recognized and interpreted quickly as being such, leading to faster intervention and help (Fischer et al., 2011). If we want to increase the likelihood of bystanders getting involved in stopping violence, the community needs to educate its members about their responsibilities as neighbors and take steps to increase people’s confidence in their ability to help (Banyard & Moynihan, 2011). Take a look at TABLE 15.2 to learn about factors that increase helping behavior.

| Why People Help | Explanation |

| Kin selection | We are more likely to help those who are close relatives, as it might promote the survival of our genes (Alexander, 1974; Hamilton, 1964). |

| Empathy | We assist others to reduce their distress (Batson & Powell, 2003). |

| Social exchange theory | We help when the benefits of our good deeds outweigh the cost (Thibaut & Kelly, 1959). |

| Reciprocial altruism | We help those who we believe can return the favor in the future (Trivers, 1971). |

| Mood | We tend to help others when our mood is good, but we also help when our spirits are low, knowing that this behavior can improve our mood (Baston & Powell, 2003; Schnall, Roper, & Fessler, 2010). |

| There are many reasons people assist each other in times of need. Above are some common explanations. | |

Now that we have seen how inaction can perpetuate human suffering, let’s take a look at the other extreme: hurtful behaviors that are in your face, unreasonable, and grounded in ignorance.

show what you know

Question 15.11

1. __________, or the tendency for people to put forth less than their best effort, might occur when individual contributions to the group are difficult to measure.

- Cognitive dissonance

- Social facilitation

- Deindividuation

- Social loafing

d. Social loafing

Question 15.12

2. In an experiment studying __________, trick-or-treating children were more likely to take extra candy and/or money if they were anonymous members of a group.

deindividuation

Question 15.13

3. __________is the tendency for people to not react in an emergency, often thinking that someone else will step in to help.

- Group polarization

- The risky shift

- The bystander effect

- Deindividuation

c. The bystander effect

Question 15.14

4. Group polarization is the tendency for a group to take a more extreme stance after deliberations and discussion. If you were in a group making an important decision, what would you tell the other group members about group polarization and how to guard against it?

Group members should know that when people hear their own opinions echoed by other members of a group, new information tends to reinforce and strengthen the group members’ original positions. And, as the members of the group listen to each other make arguments, their original positions become more entrenched. Thus, group deliberation may not be helpful when the members of the group are initially in agreement.