15.5 Aggression

THE ULTIMATE INSULT

When Julius attended high school in Uganda’s capital city of Kampala, he never told his classmates that he had been kidnapped by the LRA. “I would not tell them, or anybody, that I was a child soldier,” he says. Had the other students known, they might have called him a rebel—one of the most derogatory terms you can use to describe a person in Uganda. Calling someone a rebel is like saying that individual is worthless. “You’re poor, you do not know anything; you’re a killer,” Julius says. “It’s the same pain as in America [when] they used to call Black people ‘nigger.’ You feel that kind of pain inside you … when they call you a ‘rebel’ within your country.”

When Julius attended high school in Uganda’s capital city of Kampala, he never told his classmates that he had been kidnapped by the LRA. “I would not tell them, or anybody, that I was a child soldier,” he says. Had the other students known, they might have called him a rebel—one of the most derogatory terms you can use to describe a person in Uganda. Calling someone a rebel is like saying that individual is worthless. “You’re poor, you do not know anything; you’re a killer,” Julius says. “It’s the same pain as in America [when] they used to call Black people ‘nigger.’ You feel that kind of pain inside you … when they call you a ‘rebel’ within your country.”

LO 9 Demonstrate an understanding of aggression and identify some of its causes.

Using racial slurs and hurling threatening insults is a form of aggression. Psychologists define aggression as intimidating or threatening behavior or attitudes intended to hurt someone. Where does aggression originate? Some research suggests that aggressive tendencies are rooted in biology. Studies comparing identical and fraternal twins suggest that aggression may run in families. Identical twins, who have the same genes, are more likely than fraternal twins to share aggressive traits (Bezdjian, Tuvblad, Raine, & Baker, 2011; Rowe, Almeida, & Jacobson, 1999). Hormones also appear to be an important part of the equation, as high levels of testosterone and low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin correlate with aggression (Glenn, Raine, Schug, Gao, & Granger, 2011; Montoya, Terburg, Bos, & van Honk, 2012).

CONNECTIONS

In previous chapters, we have stated that identical twins share 100% of their genetic material, whereas fraternal twins share approximately 50%. Here, we see that identical twins are more similar on an aggressive trait than fraternal twins, which suggests there is a genetic basis for aggressive behavior.

But like any phenomenon in psychology, aggression is also influenced by environment. According to the frustration–aggression hypothesis, we can all show aggressive behavior when placed in a frustrating situation (Dollard, Miller, Doob, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939). Males tend to show more direct aggression (physical displays of aggression), while females are more likely to engage in relational aggression (gossip, exclusion, ignoring) (Archer, 2004; Archer & Coyne, 2005). One important reason for this tendency is that females run a greater risk of bodily injury resulting from a physical confrontation; therefore, they tend to opt for more relational aggression (Campbell, 1999).

In Chapter 10, we described gender differences in aggression, including a variety of causes (such as differences in testosterone levels). Here, we note that environmental factors play a role as well.

Stereotypes and Discrimination

Typically, we associate aggression with behavior, but it can also exist in the mind, coloring our attitudes about people and things. This is evidenced by the existence of stereotypes—the conclusions or inferences we make about people who are different from us, based on their group membership (such as race, religion, age, or gender). Stereotypes are often negative (Blonde people are airheads), but they can also be positive (Asians are good at math). Either way, stereotypes can be harmful.

Stereotypes are often associated with a set of perceived characteristics that we think describe members of a group. The stereotypical college instructor is absentminded, absorbed in thought, and unapproachable. The quintessential motorcycle rider is covered in tattoos, and the teenager with the tongue ring is rebelling against her parents. What do all these stereotypes have in common? They are not objective or based on empirical research. In other words, they are like bad theories of personality that characterize people based on a single behavior or trait. These stereotypes typically include a variety of predicted behaviors and traits that are rooted in subjective observations and value judgments.

When Julius was living in Louisiana, a man once approached him and said, “Is it true in Africa people still walk [around] naked?” We can only imagine where this man had gathered his knowledge of Africa (perhaps he had spent a bit too much time flipping through dated issues of National Geographic), but one thing seems certain: He was relying on an inaccurate stereotype of African people. The underlying message was clearly an aggressive one; he judged African people to be primitive and not as advanced as he was.

Groups and Social Identity

LO 10 Recognize how group affiliation influences the development of stereotypes.

Evolutionary psychologists would suggest that stereotypes allowed human beings to quickly identify the group to which they belonged (Liddle, Shackelford, & Weekes-Shackelford, 2012)—an adaptive trait, given that groups provide safety. But because we tend to think our group is superior, we may draw incorrect conclusions about members of other groups, or outsiders in general. We tend to see the world in terms of the in-group (the group to which we belong, or us) and the out-group (those who are outside the group to which we belong, or them). For better or worse, our affiliation with an in-group helps us form our social identity, or view of ourselves within a social group, and this process begins at a very young age. Those in your in-group may influence your behaviors and thoughts more than you realize. Their opinions may even shape your perception of beauty.

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Following the Crowd

Changing your mind to fit in may not be a conscious choice

Beauty is not just in the eye of the beholder—it is also in the eyes of the beholder’s friends. A study published in April in Psychological Science found that men judge a woman as more attractive when they believe their peers find that woman attractive—supporting a budding theory that groupthink is not as simple as once thought.

Researchers at Harvard University asked 14 college-age men to rate the attractiveness of 180 female faces on a scale of 1 to 10. Thirty minutes later the psychologists asked the men to rate the faces again, but this time the faces were paired with a random rating that the scientists told the men were averages of their peers’ scores. The men were strongly influenced by their peers’ supposed judgments—they rated the women with higher scores as more attractive than they did the first time. Functional MRI scans showed that the men were not simply lying to fit in. Activity in their brain’s pleasure centers indicated that their opinions of the women’s beauty really did change.

The results fit in with a new theory of conformity, says the study’s lead author Jamil Zaki. When people conform to group expectations, Zaki says, they are not concealing their own preferences; they actually have aligned their minds. In addition, the likelihood of someone conforming depends on his or her place within the group, according to a study in the December 2010 issue of the British Journal of Sociology. Members who are central are more likely to dissent because their identities are more secure. Those at the edges, who feel only partially involved or are new to the group, may have more malleable opinions. Carrie Arnold. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2011 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Discrimination

Seeing the world from the narrow perspective of our own group may lead to ethnocentrism. This term is often used in reference to cultural groups, yet it can apply to any group (think of football teams, glee clubs, college rivals, or nations). We tend to see our own group as the one that is worthy of emulation, the superior group. This type of group identification can lead to stereotyping, discussed earlier, and discrimination, which involves showing favoritism or hostility to others because of their affiliation with a group. As noted by Julius, even former child soldiers are at risk for becoming objects of discrimination.

Those in the out-group are particularly vulnerable to becoming scapegoats. A scapegoat is the target of negative emotions, beliefs, and behaviors. During periods of major stress (such as an economic crisis), scapegoats are often blamed for upsetting social situations (such as high unemployment).

Prejudice

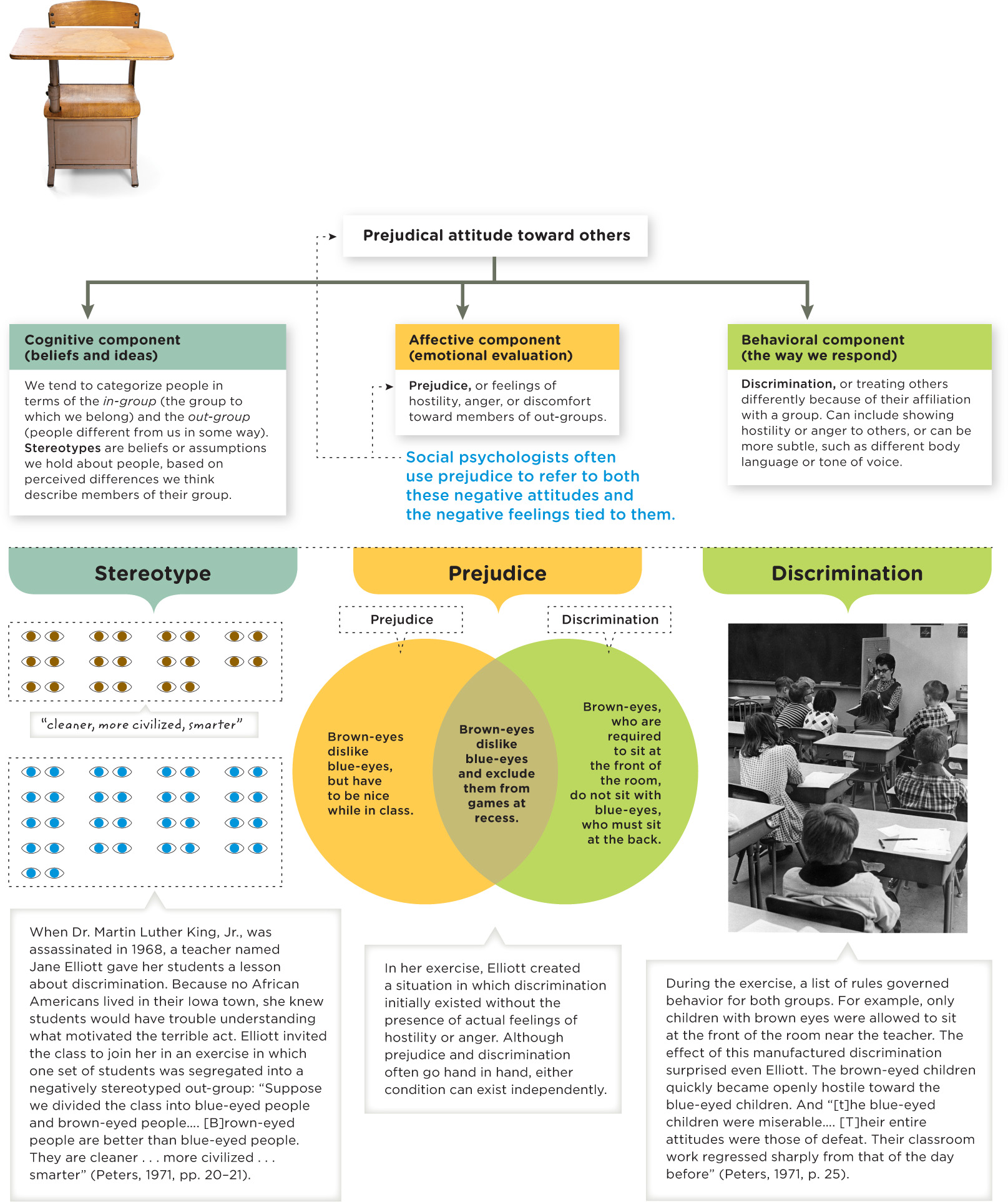

People who harbor stereotypes and blame scapegoats are more likely to feel prejudice, hostile or negative attitudes toward individuals or groups (Infographic 15.3). While prejudice and explicit racism have declined in the United States over the last half-century, there is still considerable evidence that negative attitudes persist. The same is true when it comes to sexual orientation, disabilities, and religious beliefs (Carr, Dweck, & Pauker, 2012; Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002). The causes of prejudice are complex and varied. Cognitive aspects of prejudice include the just-world hypothesis, which assumes that another person has done something to deserve the bad things happening to him. This type of belief can lead to feelings that a person should be able to control events in his life, which in turn can lead to feelings of anger and hostility. Prejudice may also result from conformity if a person seeks approval from others with strong prejudicial views.

Researchers have nevertheless concluded that prejudice can be reduced when people are forced to work together toward a common goal. In the early 1970s, Eliot Aronson and colleagues developed the notion of a jigsaw classroom. The teachers created exercises that required all students to complete individual tasks, the results of which would fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The students began to realize the importance of working cooperatively to reach the desired goal. Ultimately, every student’s contribution was an essential piece of the puzzle, and this resulted in all the students feeling valuable (Aronson, 2013).

Stereotype Threat

Stereotypes, discrimination, and prejudice are conceptually related to stereotype threat, a “situational threat” in which a person is aware of others’ negative expectations. This leads to a fear of being judged and/or treated as inferior, and it can actually undermine performance in a specific area associated with the stereotype (Steele, 1997).

African American college students are often the targets of racial stereotypes about poor academic abilities. These threatening stereotypes can lead to lowered performance on tests designed to measure ability and/or a disidentification with the role of a student (in other words, taking on the attitude that I am not a student). Interestingly, a person does not have to believe the stereotype is accurate in order for it to have an impact (Steele, 1997, 2010). If someone has a stereotypical belief (all professors are absentminded, for example), it can still have an impact even if the target doesn’t believe it’s true. One may, for instance, vehemently deny or brush off such a claim with a laugh.

There is a great deal of variation in how people react to stereotype threats (Block, Koch, Liberman, Merriweather, & Roberson, 2011). Some people simply “fend off” the stereotype, by working harder to disprove it. Others feel discouraged and respond by getting angry, either overtly or quietly. Still others seem to ignore the threats. These resilient types appear to “bounce back” and grow from the negative experience. When confronted with a stereotype, they redirect their responses to create an environment that is more inclusive and less conducive to stereotyping.

INFOGRAPHIC 15.3: Thinking About Other People

Stereotypes, Discrimination, and Prejudice

Attitudes are complex and only sometimes related to our behaviors. Like most attitudes, prejudicial attitudes can be connected with our cognitions about groups of people, our negative feelings about others (also referred to as prejudice), and our behaviors (discriminating against others). Understanding how and when these pieces connect to each other is an important goal of social psychology. Jane Elliott’s classic “Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes” exercise helps demonstrate how stereotypes, discrimination, and prejudice may be connected.

Unfortunately, stereotypes are pervasive in our society. Just contemplate all the positive and negative stereotypes associated with certain lines of work. Lawyers are greedy, truck drivers are overweight, and (dare we say) psychologists are manipulative. Can you think of any negative stereotypes associated with prison guards? As you read the next feature, think about how stereotypes come to life when people fail to think critically about their behaviors.

CONTROVERSIES

The Stanford “Prison”

August 1971: Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University launched what would become one of the most controversial experiments in the history of psychology. Zimbardo and his colleagues carefully selected 24 male college students to play the roles of prisoners and guards in a simulated “prison” setup in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology building. (Three of the selected students did not end up participating, so the final number of participants included 10 prisoners and 11 guards.) The young men chosen for the experiment were deemed “normal-average” by the researchers, who administered several psychological tests (Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973, p. 90).

August 1971: Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University launched what would become one of the most controversial experiments in the history of psychology. Zimbardo and his colleagues carefully selected 24 male college students to play the roles of prisoners and guards in a simulated “prison” setup in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology building. (Three of the selected students did not end up participating, so the final number of participants included 10 prisoners and 11 guards.) The young men chosen for the experiment were deemed “normal-average” by the researchers, who administered several psychological tests (Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973, p. 90).

After being “arrested” in their homes by Palo Alto Police officers, the prisoners were searched and booked at a local police station, and then sent to the “prison” at Stanford. The experiment was supposed to last for 2 weeks, but the behavior of the guards and the prisoners was so disturbing the researchers abandoned the study after just 6 days (Haney & Zimbardo, 1998). The guards became abusive, punishing the prisoners, stripping them naked, and confiscating their mattresses. It seemed as if they had lost sight of the prisoners’ humanity, as they ruthlessly wielded their newfound power. As one guard stated, “Looking back, I’m impressed how little I felt for them” (Haney et al., 1973, p. 88). Some prisoners became passive and obedient, accepting the guards’ cruel treatment; others were released early due to “extreme emotional depression, crying, rage, and acute anxiety”.

“… LOOKING BACK, I’M IMPRESSED HOW LITTLE I FELT FOR THEM.”

How can we explain this fiasco? The guards and prisoners, it seemed, took their assigned social roles and ran way too far with them. Social roles guide our behavior and represent the positions we hold in social groups, and the responsibilities and expectations associated with those roles.

We should note that this experiment took place during a time when prisons were under intense public scrutiny. Some scholars suggest that the participants were “acting out their stereotypic images” of guards and prisoners, and behaving in accordance with the researchers’ expectations (Banuazizi & Movahedi, 1975, p. 159).

Nevertheless, the Stanford Prison Experiment did shed light on the power of social roles. It also generated quite a storm of controversy. The study had been approved by the university’s review committee, and it did not violate the existing standards of the American Psychological Association (APA), yet many people questioned its ethical validity. The APA has since changed its guidelines, and the Stanford Prison Experiment would no longer be considered acceptable (Ratnesar, 2011, July/August). Although the ethics of the study have been questioned, its findings continue to shed light on contemporary events. In 2004 news broke that American soldiers and intelligence officials at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison had beaten, sodomized, and forced detainees to commit degrading sexual acts (Hersh, 2004, May 10). The similarities between Abu Ghraib and the Stanford Prison are remarkable (Zimbardo, 2007). In both cases, authority figures threatened, abused, and forced inmates to be naked. Those in charge seemed to derive pleasure from violating and humiliating other human beings (Haney et al., 1973; Hersh, 2004, May 10).

Before we move on to more positive things, let’s take one last detour through the dark side. You’ve learned all about aggressive behaviors, but did it ever occur to you that aggression can occur through a string of 1s and 0s? It’s aggression 2.0: Rudeness on the Internet.

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Rudeness on the Internet

Mean comments arise from a lack of eye contact more than from anonymity

Read any Web forum, and you’ll agree: people are meaner online than in “real life.” Psychologists have largely blamed this disinhibition on anonymity and invisibility: when you’re online, no one knows who you are or what you look like. A new study in Computers in Human Behavior, however, suggests that above and beyond anything else, we’re nasty on the Internet because we don’t make eye contact with our compatriots.

Researchers at the University of Haifa in Israel asked 71 pairs of college students who did not know one another to debate an issue over Instant Messenger and try to come up with an agreeable solution. The pairs, seated in different rooms, chatted in various conditions: some were asked to share personal, identifying details; others could see side views of their partner’s body through webcams; and others were asked to maintain near-constant eye contact with the aid of close-up cameras attached to the top of their computer.

Far more than anonymity or invisibility, whether or not the subjects had to look into their partner’s eyes predicted how mean they were. When their eyes were hidden, participants were twice as likely to be hostile. Even if the subjects were both unrecognizable (with only their eyes on screen) and anonymous, they rarely made threats if they maintained eye contact. Although no one knows exactly why eye contact is so crucial, lead author and behavioral scientist Noam Lapidot-Lefler, now at the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College in Israel, notes that seeing a partner’s eyes “helps you understand the other person’s feelings, the signals that the person is trying to send you,” which fosters empathy and communication. Melinda Wenner Moyer. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2012 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Much of this chapter has focused on the negative aspects of human behavior, such as obedience, stereotyping, and discrimination. And while we cannot deny the existence of these tendencies, we believe they are overshadowed by the goodness that lies within every one of us.

Prosocial Behavior

You may be wondering why we chose to include Joe and Susanne Maggio in the same chapter as Julius Achon. What do these people have in common, and why are they featured together in a chapter on social psychology? We chose these individuals because their stories send a positive message, illuminating what is best about human relationships, like the capacity to love and feel empathy. They epitomize the positive side of social psychology.

LO 11 Compare prosocial behavior and altruism.

Julius: What advice would you give to someone interested in charitable work?

Julius Achon’s actions exemplify prosocial behavior, or behavior aimed at benefiting others. After meeting the orphans in 2003, Julius kept his promise to assist them, wiring his family $150 a month to cover the cost of food, clothing, school uniforms, tuition, and other necessities—even when he and his wife were struggling to stay afloat. For 3 years, Julius was the children’s sole source of financial support. Then in 2006, when Julius was living in Portland and working for Nike, a friend helped him gather additional support from others. The following year, Julius formalized his efforts by creating the Achon Uganda Children’s Fund (AUCF), a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving the living conditions of children in the rural areas of northern Uganda. AUCF’s latest project is the construction and operation of a medical clinic in Julius’s home county of Otuke. The Kristina Acuma Achon Health Center is named after Julius’s mother, who was shot by the LRA in 2004 and died from her wounds because she lacked access to proper medical care. (For more information about the Achon Uganda Children’s Fund, please see http://achonugandachildren.org.)

If you’re wondering what became of the 11 orphans, they are all flourishing. The teenage girl in tattered clothing—the first to emerge from under the bus that morning in 2003—is now in nursing school. Sam Mugisha is following in the footsteps of Julius, running on the track team of an esteemed high school in Kampala. He is well on his way to becoming a competitive racer with an American college or professional club. As for the younger children, they are still living with the Achon family and attending school. They do their homework together at the dining room table, helping each other get through tough problems.

On the Up Side

It feels good to give to others, even when you receive nothing in return. The satisfaction derived from knowing you made someone feel happier, more secure, or appreciated is enough of a reward. The desire or motivation to help others with no expectations of payback is called altruism. Empathy, or the ability to understand and recognize another’s emotional point of view, is a major component of altruism.

Altruism and Toddlers

The seeds of altruism appear to be planted very early in life. Children as young as 18 months have been observed demonstrating helping behavior. One study found that the vast majority of 18-month-olds would help a researcher obtain an out-of-reach object, assist him in a book-stacking exercise, and open a door for him when his hands were full. It is important to note the babies did not help when the researcher intentionally put the object out of reach, or if he appeared satisfied with the stack of books. They only assisted when it appeared assistance was needed (Warneken & Tomasello, 2006). What was happening in the brains of these young children? Research has shown that particular areas of the brain (such as the medial prefrontal cortex) show increased activity in association with feelings of empathy and helping behaviors (Rameson, Morelli, & Lieberman, 2012). Given that altruism shows up so early in life, perhaps you are wondering if it is an innate characteristic. Researchers are, in fact, trying to determine if this characteristic has a genetic component, and the findings from twin studies identify “considerable heritability” of altruistic tendencies and other prosocial behaviors (Jiang, Chew, & Ebstein, 2013). But as always, we should remember that with a characteristic like altruism, we must consider the biopsychosocial perspective, and recognize the interacting forces of genetics, environment, and culture (Knafo & Israel, 2010).

Reducing Stress and Increasing Happiness

Research suggests that helping others reduces stress and increases happiness (Schwartz, Keyl, Marcum, & Bode, 2009; Schwartz, Meisenhelder, Yunsheng, & Reed, 2003). The gestures don’t have to be grand to be altruistic or prosocial. Consider the last time you bought coffee for a colleague without being asked, or gave a stranger a quarter to fill his parking meter? Do you recycle, conserve electricity, and take public transportation? These behaviors indicate an awareness of the need to conserve resources for the benefit of all. Promoting sustainability is an indirect, yet very impactful, prosocial endeavor. Perhaps you haven’t opened your home to 11 orphaned children, but you may perform prosocial acts more regularly than you realize.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 12, we discussed how altruistic behaviors can reduce stress. When helping someone else, we generally don’t have time to focus on our own problems; we also see that there are people dealing with more troubling issues than we are.

Even if you’re not the type to reach out to strangers, you probably demonstrate prosocial behavior toward your family and close friends. This giving of yourself allows you to experience the most magical element of human existence: love.

show what you know

Question 15.15

1. According to research, which of the following plays a role in aggressive behavior?

- low social identity

- low levels of the hormone testosterone

- low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin

- low levels of ethnocentrism

c. low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin

Question 15.16

2. Julius Achon sent money home every month to help cover the cost of food, clothing, and schooling for his 11 adopted children. This is a good example of

- the just-world hypothesis.

- deindividuation.

- individualistic behavior.

- prosocial behavior.

d. prosocial behavior.

Question 15.17

3. Name and describe the different displays of aggression exhibited by males and females.

Males tend to show more direct aggression (physical displays of aggression), whereas females are more likely to engage in relational aggression (gossip, exclusion, ignoring), perhaps because females have a higher risk for physical or bodily harm than males do.

Question 15.18

4. Students often have difficulty identifying how the concepts of stereotypes, discrimination, and prejudice are related. If you were sitting at a table with a sixth-grade student, how would you explain their similarities and differences?

Answers will vary, but may be based on the following information. Discrimination is showing favoritism or hostility to others because of their affiliation with a group. Prejudice is holding hostile or negative attitudes toward an individual or group. Stereotypes are conclusions or inferences we make about people who are different from us based on their group membership, such as their race, religion, age, or gender. Discrimination, prejudice, and stereotypes involve making assumptions about others we may not know. They often lead to unfair treatment of others.