2.1

As an intern at the Tranquility Rehabilitation Center, you’ll be working with people who have suffered a brain injury. Each patient has spent time in a hospital to take care of their immediate medical needs and is now learning how to live with their brain injuries. Today, you will visit Eduardo, a 71-year-old Hispanic male who has suffered a stroke that has impacted his active lifestyle. We will discuss the brain injury he has suffered and discuss how the different structures in the brain underlie his thoughts and behaviors.

2.2

Eduardo recently suffered a stroke in the left hemisphere of his cerebral cortex. His stroke occurred in a large portion of his left frontal lobe, going along the entire length of the motor cortex. Because of this brain damage, Eduardo has difficulty moving the entire right side of his body. In addition, he can’t say more than a syllable at a time. At this point in his recovery, he can only say ‘Ah,’ ‘Ba,’ ‘Ga,’ or ‘Ta.’

Eduardo’s wife, Gayle, described what a vibrant outgoing man he was until his stroke 4 weeks ago. He was vivacious and the life of the party. Gayle said that his goal, wherever he was, was to make other people happy with his jokes, magic tricks, and love of life. His favorite hobby was woodworking and many considered him to be a master with his hands. Now, Eduardo just sits in his bed or the wheelchair, looking depressed and angry. He is silent for the most part, except for occasional groans and difficult-to-understand syllables. Gayle is terrified that he won’t get better.

2.3

The cerebral cortex is highly-specialized. The left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and the right hemisphere controls the left side of the body. In fact, each hemisphere tends to outshine the other in specific tasks, a concept known as lateralization. The left hemisphere plays an important role in language production and comprehension in most people (as a memory device, think of the letter “L” for both left and language). For example, Broca’s area, which is in charge of language production, is located only within the left hemisphere. The same is true of Wernicke’s area, which is responsible for language comprehension. For most people, damage to the left hemisphere will result in difficulties with language abilities.

2.4

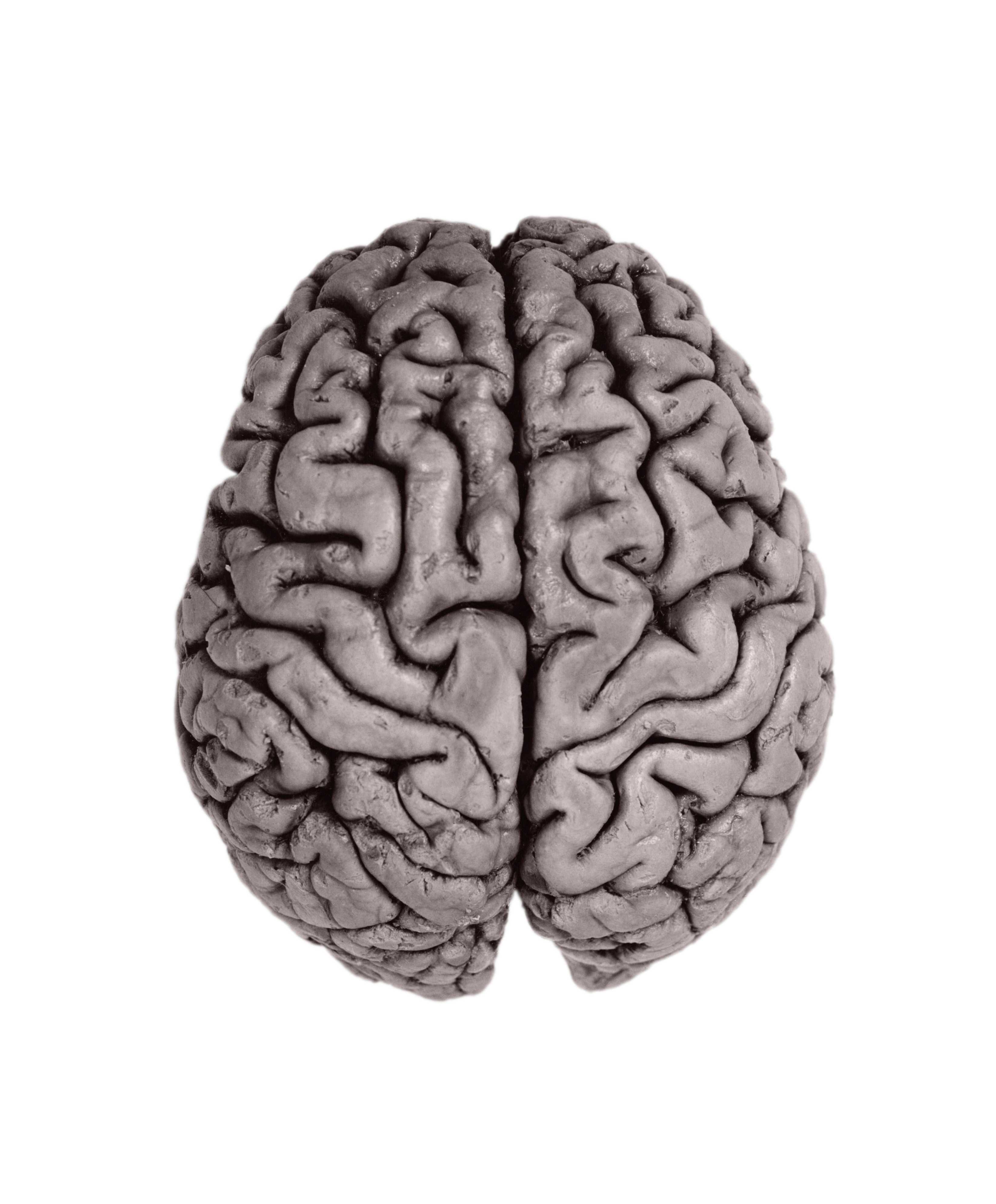

As an intern in a rehabilitation hospital for individuals with brain injuries, you need to understand both the anatomy and function of specific brain regions. For each of the following areas of the left hemisphere of the brain, select the name of the brain region. Next to each lobe is a drop down menu. Select the name of the particular region of the brain from the terms listed.

2.5

Now that you’ve identified key areas in the brain’s anatomy, let’s focus on the primary functions of these brain regions. Match the area of the brain with its specific function. Create matches by selecting the circle next to an option in the left column. Then click on the circle next to the option in the right column where you want to make the match.

2.6

2.7

Besides being responsible for motor abilities and language, the frontal lobe also plays an important role in what are called executive functions. Executive functions involve our ability to plan, hold small amounts of information in memory (working memory), inhibit thoughts and behaviors (control impulses), make judgments, and pay attention. In addition, the frontal lobes play a role in many aspects of our personality, including mood regulation. Essentially, the frontal lobes are responsible for the types of behaviors and thinking that differentiate humans from other species.

A stroke to the frontal lobes can impair many aspects of Eduardo’s life including the active lifestyle he and Gayle so fully enjoyed. He had been a happy person and loved being the center of attention. Eduardo is 4 weeks into his rehabilitation, but he has not made much progress. He is becoming more withdrawn and depressed, and yesterday he refused to participate in therapy. Gayle pleaded with him but nothing worked. Even when Gayle broke down in tears, Eduardo refused to perform his exercises or speech therapy.

2.8

What types of activities might be difficult for Eduardo after suffering his stroke? How might Gayle and Eduardo’s lives change given his loss of abilities? (Hint: Think of the functions of the frontal lobe.)

2.9

Watch the videos of two different patients who have suffered strokes. Examine the speech of both patients and notice the differences. While watching, think about which patient most resembles Eduardo. This video is of Sarah Scott who suffered a stroke at age 18.

First watch this video of Sarah Scott who suffered a stroke at age 18 and answer some questions.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

INTERVIEWER: So, what's your name?

SARAH SCOTT: Um, Scott. Oh, no. Sarah Scott.

INTERVIEWER: That's right. And how old are you?

SARAH SCOTT: I can't.

INTERVIEWER: Try.

SARAH SCOTT: I can't.

INTERVIEWER: You're 19. 19. And what happened to you?

SARAH SCOTT: Stroke.

INTERVIEWER: You had a stroke last year?

SARAH SCOTT: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: And, what happened? Can you remember what happened?

SARAH SCOTT: Um, uh, uh, school and English class.

INTERVIEWER: OK.

SARAH SCOTT: And I book. And I read it aloud, but I can't, [? because ?] straight. So I [INAUDIBLE]. And, also, it's the same as-- the same as-- kind of thing as-- you know.

INTERVIEWER: Pins and needles?

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah. The same. And also, this foot.

INTERVIEWER: Leg.

SARAH SCOTT: And the-- yeah. Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: And what happened after the stroke with your speech?

SARAH SCOTT: But, I can't.

INTERVIEWER: You have speech problems. So, you were going to go to university. What are you doing now?

SARAH SCOTT: What?

INTERVIEWER: What do you doing now everyday?

SARAH SCOTT: Oh, um, speech and speech--

INTERVIEWER: Therapy.

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah. And also, writing.

INTERVIEWER: What helps you to speak? When you write things down, it helps you, doesn't it?

SARAH SCOTT: Yes. I don't that it's-- I can't-- sometimes I'll write it down, because it's easier, and also speaking is easier. So, I don't know.

INTERVIEWER: A mixture.

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah. And I can't write like one word. I'm find that sometimes long sentences I can't read, I can't write.

INTERVIEWER: Can you read a book?

SARAH SCOTT: No.

INTERVIEWER: Do you want to read the book?

SARAH SCOTT: Yes. But I can't.

INTERVIEWER: You'd like to though.

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: And what about your friends? Do you still see your friends?

SARAH SCOTT: A little.

INTERVIEWER: Is that hard for them?

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah, because I can't speak a little, but it's harder. And I can't-- sometimes it's harder, because-- speaking, like, my friends-- like, it's too hard and I don't like it. So, it's hard then friends [? than-- ?]

INTERVIEWER: Family?

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: It's been nine months now since your stroke, not even a year. So that's good, because at first, you couldn't walk, you couldn't swallow, could you?

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah.

INTERVIEWER: Do you remember being in hospital?

SARAH SCOTT: I tiny bit, but I can't.

INTERVIEWER: And didn't know why you had a stroke?

SARAH SCOTT: Heart. A hole in the heart. And I close up, so--

INTERVIEWER: You had an operation?

SARAH SCOTT: Yeah.

2.10

2.11

Now, watch the video below of Byron Peterson, who also suffered a stroke. When someone suffers a stroke, where in the brain that stroke occurs impacts different functions. Listen carefully to how Byron speaks. Pay attention to how well he follows the questions and how well he speaks. Note any differences between Byron and Sarah.

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

- English Captions

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

This is a modal window.

WOMAN: Hi, Byron. How are you?

BYRON; I'm happy. Are you pretty? You look good.

WOMAN: What are you doing today?

BYRON: We stayed with the water over here at the moment, talked with the people of the them over there. They're diving for them at the moment. They'll save in the moment, have water very soon for him, with luck for him.

WOMAN: So we're on a cruise, and we're about to get to Juno.

BYRON: We will sort right here, and they'll save their hands right there with them.

WOMAN: And what were we just doing with the iPad?

BYRON: Right at the moment, they don't show a darn thing.

WOMAN: The iPad that we were doing. Like here?

BYRON: I'd like my change for me, and change hands for me. It was happy. I would talk with Donna sometimes. We're all with them. Other people are working with them-- them. I'm very happy with them.

WOMAN: Good.

BYRON: This girl with fairly good, and happy, and I played golf, and hit the trees. We play out with the hands. We save a lot of hands on hold for people's for us, other hands. I don't know what you get, but I talk with a lot of hand for him. Sometimes, I might talk of anymore to say.

2.12

The video of Sarah showed her recovery of speech function after intense rehabilitation. Sarah was 18 when she had her stroke. Eduardo is 71. What differences in Eduardo’s recovery would you expect to see if he were 50 years younger? Specifically, define and apply the idea of neuroplasticity.

2.13

That was some first day here at Tranquility Rehabilitation Center! You did a fantastic job of examining Eduardo and recording the brain damage his stroke caused. We also hope that this experience has shown you how difficult it is to lose brain functions we take for granted.

Based on your experience working as an intern for Tranquility Rehabilitation Center, discuss the main points you learned about a brain injury to the frontal lobe and the loss of certain brain functions. After examining Eduardo, how has your idea of coping with such an injury changed? How might a brain injury of this sort impact you and/or your family’s lives?