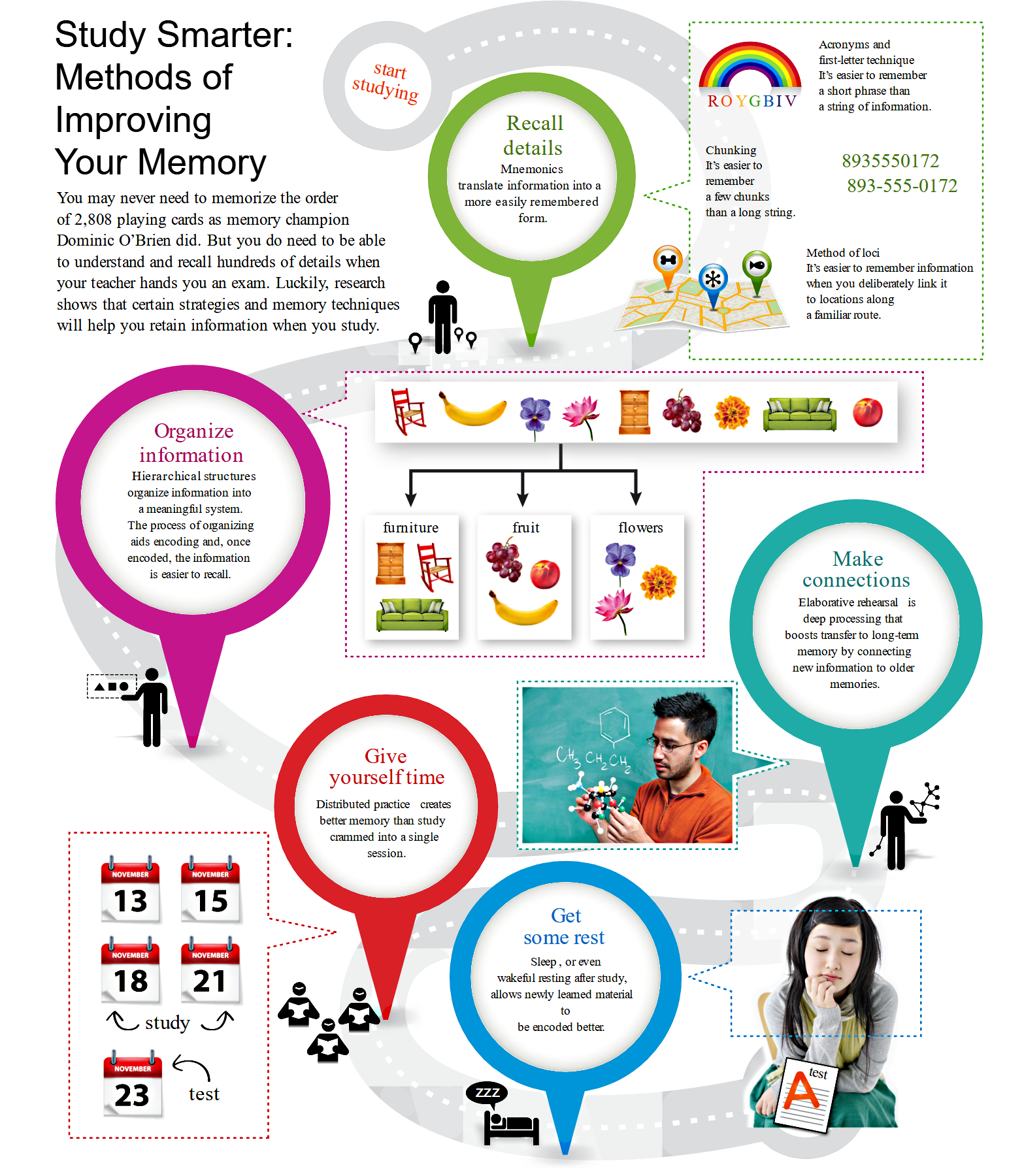

You spent all of last night cramming for your psychology exam. You were sure that you had learned all the necessary information after all that studying. You made it to the test on time, but you struggled to remember a lot of the material. You are frustrated and pretty sure you received a bad grade on the exam despite pulling an all-nighter.

What can you do to improve your performance on the next exam? To help you out, we’ll introduce you to some helpful study skills and help you think through the best way to use those skills. To get started, read the following paragraphs from an article in Scientific American titled “Why Testing Boosts Learning.”

Next, read the following paragraph from the same article, then answer the questions about what you have read in the first two paragraphs:

As expected, students in the practice test group were better at remembering the word pairs during a final exam a week later. But Rawson and Pyc also asked students to tell them their keywords—for instance, “bird” might serve as a bridge between wingu and cloud—and they revealed that the people in the practice test group not only remembered more of their keywords, but they were more likely to have changed their keyword before restudying the word pairs than those who had not been tested. As the researchers reported in Science last October, these results suggest that testing improves memory by strengthening keyword associations and weeding out clues that do not work.

Anderson, A. (2011, January 1). Why testing boosts learning: Getting quizzed strengthens memory-jogging keyword clues. Scientific American Mind. Retrieved from Why Testing Boosts Learning - Scientific American(Opens in a new window)