11.2 Stress and Your Health

CONNECTIONS

We introduced the fight-

TROUBLE UNDERCOVER Meet Sergeant Michelle, a long-

TROUBLE UNDERCOVER Meet Sergeant Michelle, a long-

Faced with the prospect of being gunned down by a drug dealer, Michelle most likely experienced the sensations associated with the fight-

Fight or Flight

LO 4 Identify the brain and body changes that characterize the fight-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we introduced the parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the “rest-

When faced with a threatening situation, portions of the brain, including the hypothalamus, activate the sympathetic nervous system, which leads to the secretion of catecholamines, such as epinephrine and norepinephrine. These hormones cause heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and blood flow to the muscles to increase. Meanwhile, digestion slows and the pupils dilate.

Physiological responses prepare us for an emergency by efficiently managing the body’s resources. Once the emergency has ended, the parasympathetic system reverses these processes by reducing heart rate, blood pressure, and so on. If a person is exposed to a threatening situation for long periods of time, the fight-

Endocrinologist Hans Selye proposed that the body passes through a predictable sequence of changes in response to stress. Selye’s general adaptation syndrome includes three phases: the alarm stage, the resistance stage, and the exhaustion stage.

LO 5 Outline the general adaptation syndrome (GAS).

general adaptation syndrome (GAS) A specific pattern of physiological reactions to stressors that includes the alarm stage, resistance stage, and exhaustion stage.

GENERAL ADAPTATION SYNDROME Hans Selye, introduced earlier in the chapter, identified police work “as likely the most stressful occupation in the world” (according to Violanti, 1992, p. 718). One of the first to suggest the human body responds to stressors in a predictable way, Selye (1936) described a specific pattern of physiological reactions, which he called the general adaptation syndrome (GAS).

According to this theory, the body passes through three stages (Infographic 11.2). The first is the alarm stage, or the body’s initial response to a threatening situation, similar to the fight-

INFOGRAPHIC 11.2

LO 6 Describe the function of the hypothalamic–

Synonyms

hypothalamic–

HYPOTHALAMIC–

Synonyms

health psychology behavioral medicine

B lymphocytes B cells

T lymphocytes T cells

Psychologists have been exploring this issue for decades, trying to determine how stress influences human health. Early in the 1960s, the field of health psychology began to gather momentum, exploring the biological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to health and illness. Health psychology seeks to explain how food choices, social interactions, and living environments affect our predisposition to illness. Researchers in this field contribute to health education, helping people develop positive eating and exercise habits. They conduct public policy research that influences health-

Is Stress Making You Sick?

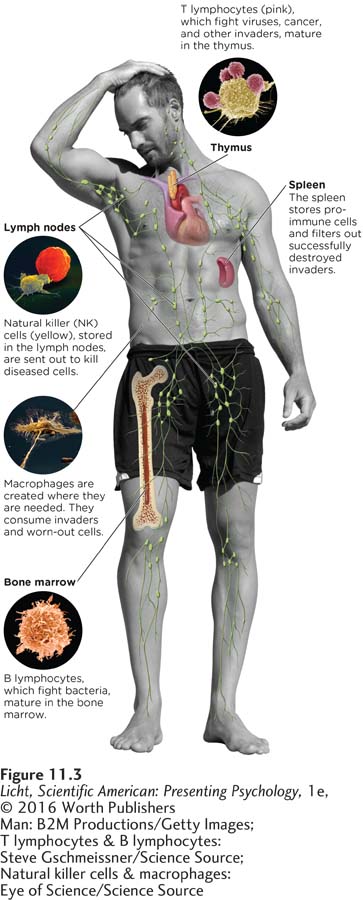

Our immunity derives from a complex system involving structures and organs throughout the body that support the work of specialized cell types to keep us healthy.

LO 7 Explain how stressors relate to health problems.

lymphocyte Type of white blood cell produced in the bone marrow whose job is to battle enemies such as viruses and bacteria.

Before we explore the connection between stress and illness, we must understand how the body deals with illness in the first place. Let’s take a side trip into introductory biology and learn about the body’s main defense against disease—

Like a platoon of soldiers, the immune system has a defense team to fight off invaders. Should the intruder(s) get past the skin, the macrophages (“big eaters”) are ready to attack. These cells hunt and consume invaders as well as worn-

Earlier we mentioned that stressors are correlated with health problems. But how exactly do stressors such as beliefs and attitudes affect the physical body? In other words, what is the causal relationship between stressors and illness? Let’s address this question by examining some illnesses thought to be closely linked to stressors (Cohen, Miller, & Rabin, 2001).

A group of Marines practice patrolling techniques as part of their combat training. Long-

GASTRIC ULCERS AND STRESSORS Gastric ulcers have long been thought to be associated with stress, but the nature of this link has not always been clear. For many years, it was believed that stress alone caused gastric ulcers, but researchers then started to suspect other culprits. They found evidence that the bacterium H. pylori plays an important role. This does not mean that H. pylori is always to blame, however. Some people who carry the bacteria never get ulcers, while others develop ulcers in its absence. It seems that many factors influence the development of ulcers, among them tobacco use, family history, and excess gastric acid (Fink, 2011).

CANCER AND STRESSORS Cancer has also been associated with stress, both in terms of risk and development. Specifically, stress has been linked to the suppression of T lymphocytes and NK cells, which help monitor immune system reactions to the invasion of developing tumors. When a person is exposed to stressors, the body is less able to mount an effective immune response, which increases the risk of cancer (Reiche, Nunes, & Morimoto, 2004).

In the United States and other Western countries, breast cancer is the greatest cancer risk for women, and some evidence suggests it is associated with stress. In a meta-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 6, we discussed the malleability of memory. Problems may arise when study participants are asked to remember events and illnesses from the past. Here we are describing a prospective study, which does not require participants to retrieve information from the distant past, thus reducing opportunities for error.

Stress has been correlated with other types of cancer, though not always in the expected direction. One group of researchers examined the relationship between chronic daily stressors and the development of colorectal cancer using a prospective study in which nearly 12,000 Danes (who had never been diagnosed with colorectal cancer) were followed for 18 years (Nielsen et al., 2008). The researchers noted some surprising findings, particularly with respect to females. Women who reported higher levels of “stress intensity” and “daily stress” were less likely to develop colon cancer during the course of the study. In contrast, men with “high stress intensity” experienced higher levels of rectal cancer, although this association was not considered to be strong because only a small number actually developed this kind of cancer. The authors suggested that a variety of physiological, mental, and behavioral factors (for example, sex hormones, burnout, and increased alcohol intake) were involved in the relationship between high stress and lower rates of colon cancer in the women.

Why can’t researchers agree on the link between cancer and stressors? Part of the problem is that studies are focusing on stressors of different durations. Short-

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND STRESSORS The same is true for the relationship between stressors and cardiovascular disease. Dimsdale (2008) noted that over 40,000 citations popped up in a medical database when the search terms were “stress” and “heart disease.” What constitutes a stressor in this context? Earthquakes, unhappy marriages, and caregiving burdens are just a few stressors associated with a variety of outcomes or vulnerabilities, ranging from abnormalities in heart function to sudden death. Earlier we discussed socioeconomic status and stress; it turns out that both of those variables are factors in cardiovascular disease. Joseph and colleagues reported fivefold higher odds of experiencing “cardiometabolic events” (within 5 years) for people who became unemployed as a result of Hurricane Katrina, a devastating natural disaster that occurred in 2005 (Joseph, Matthews, & Myers, 2013, March 25). The faster people get support to decrease “socioeconomic disruptions” related to a disaster, the better their health outcomes.

Paramedics transfer a patient from ambulance to emergency room. The patient is clearly experiencing a health crisis, but the paramedics face their own set of health risks. Working odd hours, not getting enough exercise, eating poorly, and dealing with the ongoing stresses of paramedic work make it challenging to stay healthy.

Other stressors have also been linked to heart disease. “Social-

The mechanisms of the causal relationship between stressors and cardiovascular disease are not totally understood (Straub, 2012). However, we do know that an increase of fatty deposits, inflammation, and scar tissue within artery walls, that is, atherosclerosis, is a dangerous risk factor for stroke and heart disease (Go et al., 2013). With this type of damage, blood flow in an artery may become blocked or reduced. Researchers are not sure exactly how atherosclerosis starts, but one theory suggests that it begins with damage to the inner layer of the artery wall, which may be caused by elevated cholesterol and triglycerides, high blood pressure, and cigarette smoke (American Heart Association, 2012). It is important to note that stressors cannot be shown to cause changes in cardiovascular health (Dimsdale, 2008). Although there is a clear correlation between biopsychosocial stressors and cardiovascular disease, we cannot say with certainty that these stressors are responsible (Ferris et al., 2012).

Stress and Substances

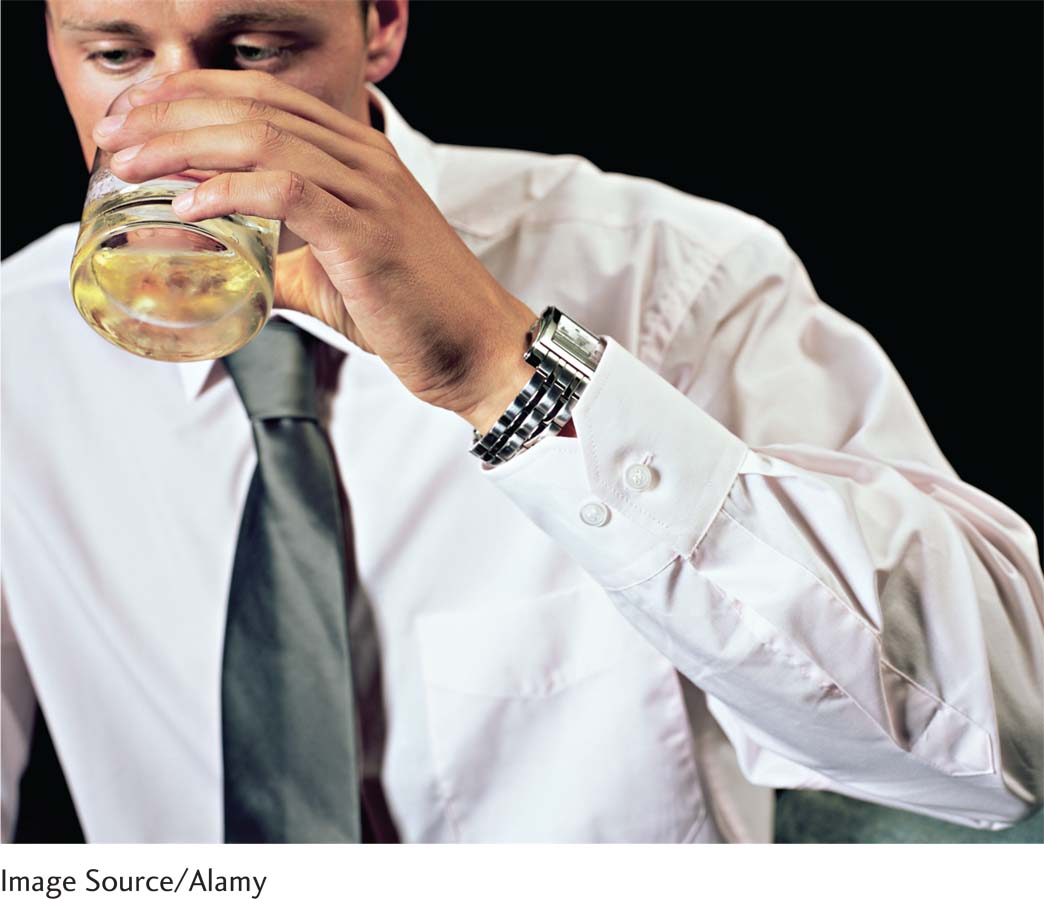

Stress often exerts its harmful effects indirectly (Cohen et al., 2001). When faced with stressors, we may sleep poorly, eat erratically, and perhaps even drink more alcohol. These behavioral tendencies can lead to significant health problems (Benham, 2010; Ng & Jeffery, 2003).

SMOKING AND STRESS In Chapter 4, on consciousness, we described how drugs are used to alleviate pain, erase memories, and toy with various aspects of consciousness. But a discussion of drugs is also in order here, because many people use drugs to ease stress. Smokers report that they smoke more cigarettes in response to stressors, as they believe it improves their mood. The association between lighting up and feeling good is one reason smokers have such a hard time quitting (Lerman & Audrain-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 4, we discussed the concept of physiological dependence and tolerance. When we use drugs, such as nicotine, they alter the chemistry of the brain and body. Over time, the body adapts to the drug and therefore needs more and more of it to create the original effect.

How do we get people to kick a habit that is perceived as so pleasurable? One effective way is to meet them where they are, rather than taking a one-

Some people turn to alcohol and other drugs for stress relief, but the self-

ALCOHOL AND STRESS Much the same could be said for alcohol, another drug frequently used to “take the edge off,” or counteract, the unpleasant feelings associated with stress. Perhaps you know someone who “needs” a drink to relax after a rough day. Psychologists explain this type of behavior with the self-

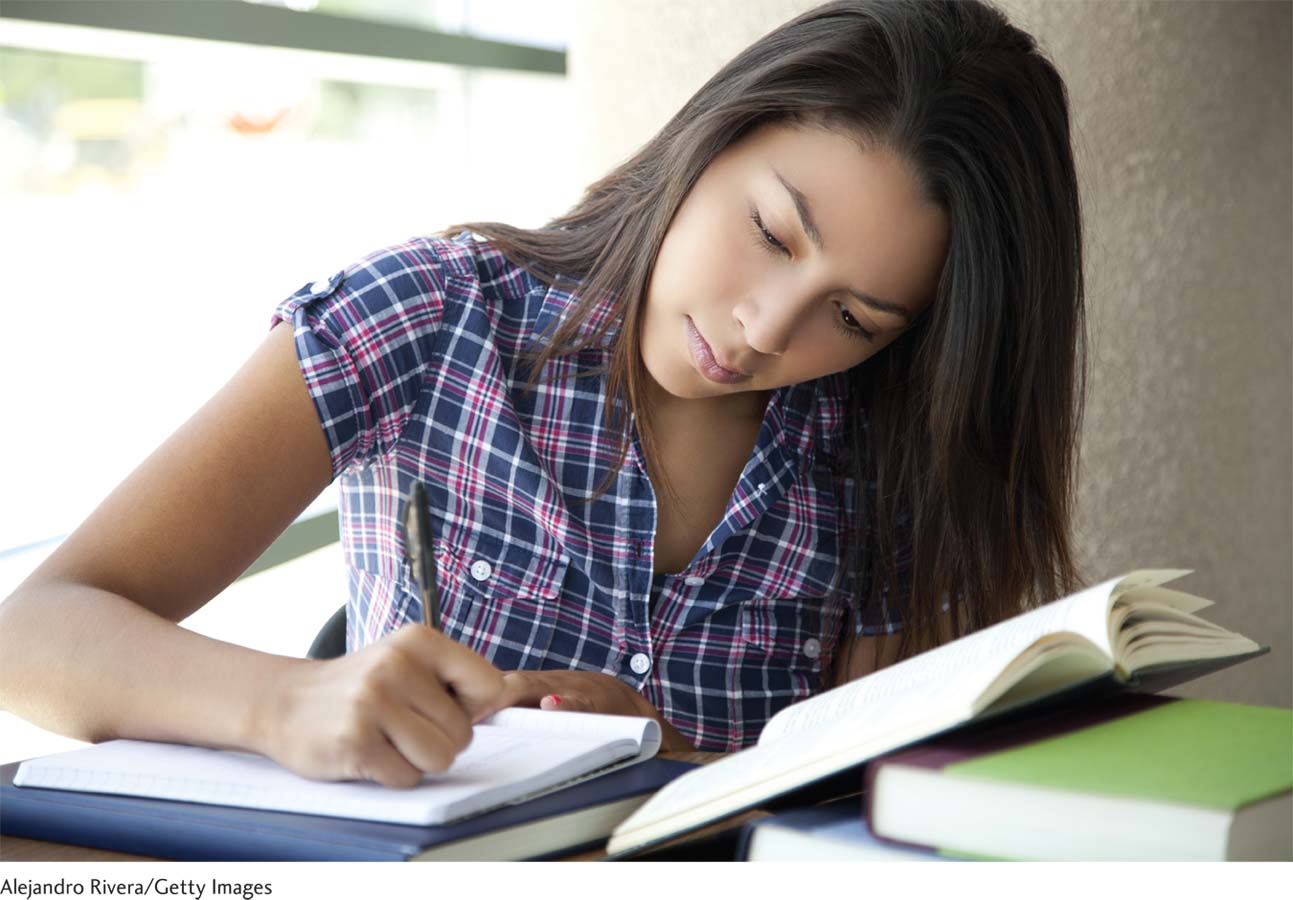

Teenagers, in particular, appear to rely on alcohol to cope with daily hassles (Bailey & Covell, 2011). Adolescents frequently face disagreements with family members, teachers, and peers. They may worry about how they look and whether they are succeeding in school. We need to help adolescents find new and more “healthy” ways to handle these hassles. This means providing more support in schools, and perhaps educating teachers and counselors about the tendency to self-

ADRENALINE JUNKIES What lures a person into an EMS career? The reward of alleviating human suffering is “incredible,” according to Kehlen. Imagine walking into the home of a diabetic who is lying on the floor, unconscious and surrounded by trembling family members. You insert an IV line into the patient’s vein and deliver D50, a dextrose solution that increases blood sugar. In a few moments, the person is awake as if nothing happened. The family is ecstatic; you have saved their loved one from potential brain damage or death. “People that like to do selfless acts, I think, are made for this job,” Kehlen says. And for those who enjoy a good challenge, both physical and mental, an EMS career will not disappoint. Try working for 24 hours in a row, making life-

ADRENALINE JUNKIES What lures a person into an EMS career? The reward of alleviating human suffering is “incredible,” according to Kehlen. Imagine walking into the home of a diabetic who is lying on the floor, unconscious and surrounded by trembling family members. You insert an IV line into the patient’s vein and deliver D50, a dextrose solution that increases blood sugar. In a few moments, the person is awake as if nothing happened. The family is ecstatic; you have saved their loved one from potential brain damage or death. “People that like to do selfless acts, I think, are made for this job,” Kehlen says. And for those who enjoy a good challenge, both physical and mental, an EMS career will not disappoint. Try working for 24 hours in a row, making life-

But there appears to be something else drawing people into the EMS profession. You might call it the “adrenaline junkie” factor. Ever since Kehlen was a small boy, he enjoyed a certain amount of risk taking. He was the kid who fearlessly scaled the monkey bars and leaped off the jungle gym, and many of his colleagues claim they were the same way. “All of us probably thought we were 10 feet tall and made of steel,” Kehlen says, careful to note that “daring” is not the same as “reckless.” One must be calculating when it comes to determining what risks are worth taking.

The adrenaline junkie quality is also apparent in some police officers, according to Sergeant Michelle. An officer patrolling a city beat probably experiences the so-

Is there really some common adrenaline junkie tendency among police officers, EMS providers, and other first responders? That remains an open question. We do know, though, that first responders are frequently exposed to highly stressful events (Anderson, Litzenberger, & Plecas, 2002; Gayton & Lovell, 2012). With all this exposure to violence and trauma, how do the body and mind hold up? The answer is probably different for each individual, but constant stress certainly has the potential to erode health and well-

Too Much Cortisol

LO 8 List some consequences of prolonged exposure to the stress hormone cortisol.

Earlier we discussed the stress hormone cortisol, which plays an important role in mobilizing the body to react to threats and other stressful situations. Cortisol is useful if you are responding to immediate danger, like a raging fire or ruthless assailant. However, you don’t want cortisol levels to remain high for long. Both body and brain are impacted when the cortisol system flips into overdrive.

CORTISOL AND KIDS The negative effects of stress are apparent very early in life—

Now consider the types of stressors some preschool children confront every day. Research shows that conflicts at home can increase cortisol levels in children (Slatcher & Robles, 2012). Verbal exchanges such as the child exclaiming, “No! I don’t want to!” and parents saying, “You are going to shut your mouth and be quiet!” are exactly the types of conflicts associated with increased cortisol levels. Cortisol activity may help explain why exposure to conflict during childhood seems to pave the way for health problems (Slatcher & Robles, 2012). Clearly, cortisol plays a role in early development. But how does this stress hormone affect adults?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 6, we presented the concept of working memory, which refers to how we actively maintain and manipulate information in short-

CORTISOL ON THE JOB High cortisol levels can have life-

Other research suggests that heightened cortisol levels may have the opposite effect. When police officers had to make threat-

psychoneuroimmunology (sī-kō-'n(y)u̇r-

Heightened cortisol levels can help or hinder a person studying for a math test. For people with “higher working memory” and low math anxiety, cortisol seems to boost performance, but it has the opposite effect when math anxiety is high (Mattarella-

PSYCHONEUROIMMUNOLOGY We have now discussed some of the effects of short-

The field of health psychology, which draws on the biopsychosocial model and psychoneuroimmunology, has shed light on the complex relationship between stress and health (Havelka, Lučanin, & Lučanin, 2009). Now that we understand how profoundly stressors can impact physical well-

show what you know

Question 1

1. According to the ____________, the human body responds in a predictable way to stressors, following a specific pattern of physiological reactions.

general adaptation syndrome (GAS)

Question 2

2. As a police officer, Michelle has found herself in life-

alarm stage

exhaustion stage

diseases of adaptation

acculturative stress

a. alarm stage

Question 3

3. ____________ helps maintain balance in the body by overseeing the sympathetic nervous system, as well as the neuroendocrine and immune systems.

The general adaptation syndrome

The exhaustion stage

The hypothalamic–

pituitary– adrenal system Eustress

c. The hypothalamic–

Question 4

4. Infants of mothers subjected to extreme stressors may be born prematurely, have low birth weights, and exhibit behavioral difficulties. These outcomes result from increased levels of the stress hormone____________.

H. pylori

lymphocytes

cortisol

NK cells

c. cortisol

Question 5

5. Why are people under stress more likely to get sick?

When the body is expending its resources to deal with an ongoing stressor, the immune system is less powerful, and the work of the lymphocytes is compromised. During times of stress, people tend to sleep poorly and eat erratically, and may increase their drug and alcohol use, along with other poor behavioral choices. These tendencies can lead to health problems.