11.3 Factors Related to Stress

First responders encounter a wide variety of scenarios, ranging in intensity from five-

Conflicts

Police officers deal with a variety of conflicts in their daily work. Imagine you are an officer trying to decide whether to arrest a parent suspected of child abuse. If you make the arrest, the child may be removed from the home and placed in foster care (not an ideal scenario), but at least the threat of abuse is removed. This is an approach–

LO 9 Identify different types of conflicts.

When people think of conflict, they may imagine arguments and fist fights, but conflict can also refer to the discomfort one feels when making tough choices. In an approach–

Let’s see how these types of conflict might arise in police work:

approach–

approach conflict: Suppose you are a 30-year veteran of the Houston police department. You can either retire now and begin receiving a pension, or continue working in a profession you find rewarding. Both options are positive. approach–

avoidance conflict: Now imagine you are a police officer contemplating whether to arrest a mother and father suspected of child abuse. If you make the arrest, all of the children in the home will be placed in foster care, an unfamiliar, often frightening environment for children. Something good will come out of the change (the children are no longer at risk of being abused), but the downside is that they will be thrown into an unfamiliar environment.avoidance–

avoidance conflict: You are new to the police force. It is your second day on the job, and you are given a choice between the following two tasks: ride in the squad car with a partner you dislike or stay in the station all day and answer calls (a very boring activity). Both decisions lead to negative outcomes.

Conflicts can be even more complicated than this. A double approach–

Sometimes conflicts and other stressors pile up so high they become difficult to tolerate. When we can no longer deal with stress in a constructive way, we experience what psychologists call burnout.

A nurse holds a patient’s IV bag in the emergency room. Nursing is one of the professions associated with high burnout—

AMBULANCE BURNOUT Kehlen has been in the EMS field for nearly a decade, and most of that time he has spent working for a private ambulance company. He estimates that the average ambulance worker lasts about 8 years before quitting to pursue another line of work. What makes this career so hard to endure? The pay is modest, the 24-

AMBULANCE BURNOUT Kehlen has been in the EMS field for nearly a decade, and most of that time he has spent working for a private ambulance company. He estimates that the average ambulance worker lasts about 8 years before quitting to pursue another line of work. What makes this career so hard to endure? The pay is modest, the 24-

burnout Emotional, mental, and physical fatigue that results in reduced motivation, enthusiasm, and performance.

It might not surprise you that the EMS profession has one of the highest rates of burnout (Gayton & Lovell, 2012). Burnout refers to emotional, mental, and physical fatigue that results from repeated exposure to challenges, leading to reduced motivation, enthusiasm, and performance. People who work in the helping professions, such as nurses, mental health professionals, and child protection workers, are clearly at risk for burnout (Jenaro, Flores, & Arias, 2007; Linnerooth, Mrdjenovich, & Moore, 2011; Rupert, Stevanovic, & Hunley, 2009).

I Can Deal: Coping with Stress

Police officers are also susceptible to burnout. The nature of the work they do, the size of the department they work in, and the amount of trust in their coworkers all play a role (McCarty, Schuck, Skogan, & Rosenbaum, 2011, January 7). To survive and thrive in this career, you must excel under pressure. Police departments need officers who are emotionally stable and capable of making split-

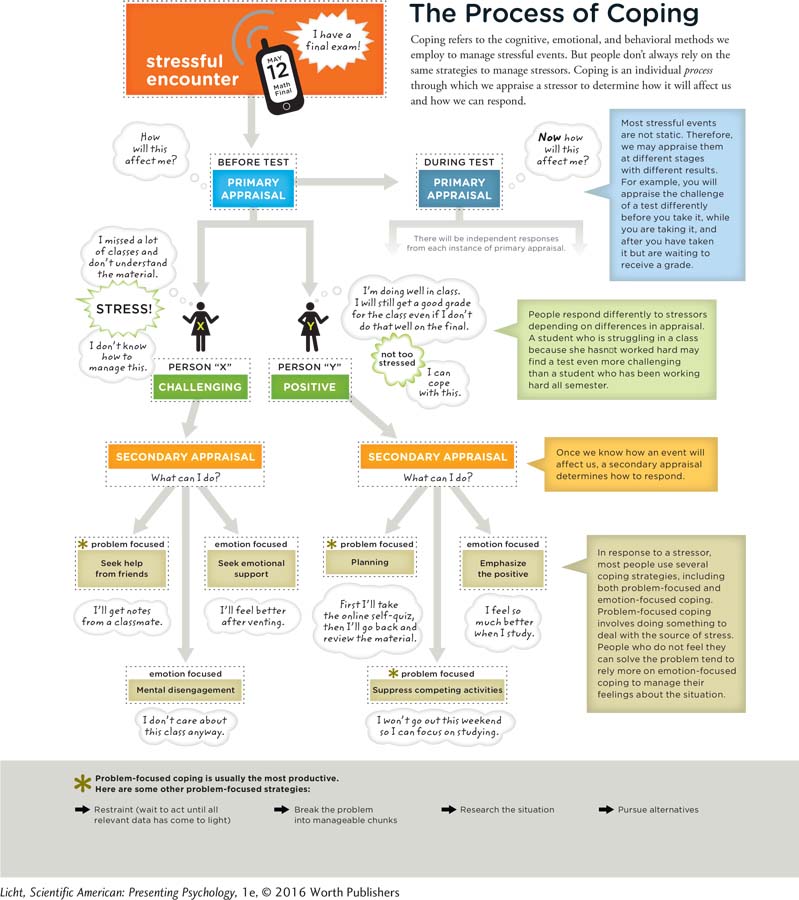

LO 10 Illustrate how appraisal influences coping.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we described the cognitive appraisal theory of emotion, which suggests that emotion results from the way people appraise or interpret interactions they have. We appraise events based on their significance, and our subjective appraisal influences our response to stressors.

coping The cognitive, behavioral, and emotional abilities used to effectively manage something that is perceived as difficult or challenging.

primary appraisal One’s initial assessment of a situation to determine its personal impact and whether it is irrelevant, positive, challenging, or harmful.

secondary appraisal An assessment to determine how to respond to a challenging or threatening situation.

APPRAISAL AND COPING Needless to say, people respond to stress in their own unique ways. Psychologist Richard Lazarus (1922–

INFOGRAPHIC 11.3

problem-

emotion-

There are two basic types of coping. Problem-

IT’S A PERSONAL THING In June 2011 Eric began his second run through Onondaga’s police training program. This time around, he nailed the Emergency Vehicle Operations Course (EVOC). “I can’t even describe to you how great it felt.” The secret to his success? “Instead of worrying about everything, I had fun,” Eric says. “Once you relax … [it] helps you focus better.” Eric graduated in December 2011. He soon landed a position with a local police department.

IT’S A PERSONAL THING In June 2011 Eric began his second run through Onondaga’s police training program. This time around, he nailed the Emergency Vehicle Operations Course (EVOC). “I can’t even describe to you how great it felt.” The secret to his success? “Instead of worrying about everything, I had fun,” Eric says. “Once you relax … [it] helps you focus better.” Eric graduated in December 2011. He soon landed a position with a local police department.

“Police training is different everywhere,” says Eric, who chose the police academy at Onondaga Community College because of its rigor. No training program can totally prepare you for police work, but the academy makes every effort to simulate real-

LO 11 Describe Type A and Type B personalities and explain how they relate to stress.

Type A personality Competitive, aggressive, impatient, and often hostile pattern of behaviors.

Type B personality Relaxed, patient, and nonaggressive pattern of behaviors.

TYPE A AND TYPE B PERSONALITIES Personality appears to have a profound effect on coping style and predispositions to stress-

Olympic swimmer Ryan Lochte appears to have what psychologists call a Type B personality—

Although many years of research confirmed the relationship between Type A behavior and coronary heart problems, some researchers began to report findings inconsistent with this (Smith & MacKenzie, 2006). Failure to reproduce the results led some to question the validity of this relationship, although one major factor was a lack of consistency in research methodology. For example, some studies used samples with high-

TYPE D PERSONALITY More recently, researchers have suggested another personality type that may better predict how patients fare when they already have heart disease: Type D personality, where the “D” refers to distress (Denollet & Conraads, 2011). Someone with Type D personality is characterized by emotions like worry, tension, bad moods, and social inhibition (avoids confronting others, poor social skills). There is a clear link between Type D characteristics and a “poor prognosis” in patients with coronary heart disease (Denollet & Conraads, 2011). In other words, people who have heart problems and exhibit these Type D characteristics are more likely to struggle with their illness. It could be that people with Type D personality tend to avoid dealing with their problems directly and don’t take advantage of social support. Such an approach might lead to poor choices about coping with stressors over time (Martin et al., 2011).

hardiness A personality characteristic indicating an ability to remain resilient and optimistic despite intensely stressful situations.

THE THREE Cs OF HARDINESS Clearly, not everyone has the same tolerance for stress (Ganzel, Morris, & Wethington, 2010; Straub, 2012). Some people seem capable of handling intensely stressful situations, such as war and poverty. These individuals appear to have a personality characteristic referred to as hardiness, meaning that even when functioning under a great deal of stress, they are very resilient and tend to remain positive. Kehlen, who considers himself “a very optimistic person,” may fit into this category, and findings from one study of Scottish ambulance personnel suggest that EMS workers with this characteristic are less likely to experience burnout (Alexander & Klein, 2001).

Kobasa (1979) and others have studied how some executives seem to withstand the effects of extremely stressful jobs. Their hardiness appears to be associated with three characteristics: feeling a strong commitment to work and personal matters; believing they are in control of the events in their lives and not victims of circumstances; and not feeling threatened by challenges, but rather seeing them as opportunities for growth.

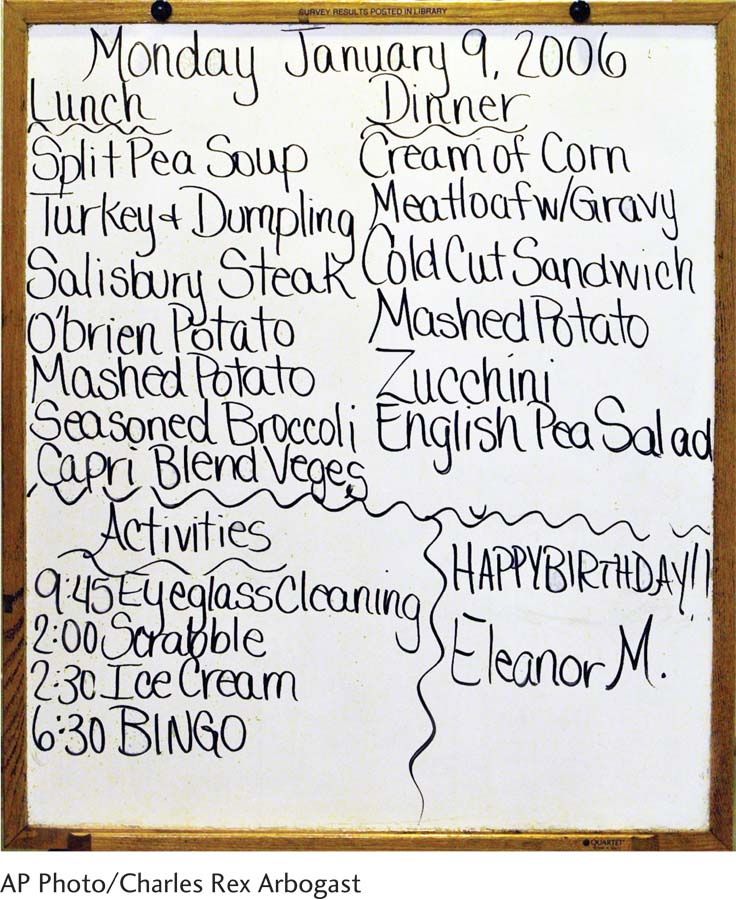

I Am in Control

A nursing home white board displays a list of menu items and activities that residents can choose from. One study found that putting nursing home residents in charge of their daily activities led to increased levels of energy, health, and social engagement. Their empowerment was also associated with lower death rates (Rodin & Langer, 1977).

The ability to manage stress is very much dependent on one’s perceived level of personal control. Psychologists have consistently found that people who believe they have control over their lives and circumstances are less likely to experience the negative impact of stressors than those who do not feel the same control. For example, Langer and Rodin (1976) conducted a series of studies using nursing home residents as participants. Residents in a “responsibility-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 10, we discussed locus of control, a key component of personality. Someone with an internal locus of control believes the causes of outcomes reside within him. A person with an external locus of control thinks causes of outcomes reside outside him. Here, we see that higher personal control is associated with better health outcomes.

Researchers have examined how having a sense of personal control relates to a variety of health issues across all ages. Feelings of control are linked to how patients fare with some diseases. Cancer patients who exhibit a “helpless attitude” regarding their disease seem more likely to experience a recurrence of the cancer than those with perceptions of greater control. Why would this be? Women who have had breast cancer and believe they maintain control over their lifestyle, through diet and exercise, are more likely to make proactive changes related to their health, and perhaps reduce risk factors associated with recurrence (Costanzo, Lutgendorf, & Roeder, 2011). The same type of relationship is apparent in cardiovascular disease; the less control people feel they have, the greater their risk (Shapiro, Schwartz, & Astin, 1996). As we pointed out, having choices increases a perceived sense of control.

Feelings of control may also have a more direct effect on the body; for example, a sense of powerlessness is associated with increases in catecholamines and corticosteroids, both key players in a physiological response to stressors. Some have suggested a causal relationship between feelings of perceived control and immune system function; the greater the sense of control, the better the functioning of the immune system (Shapiro et al., 1996). But these are correlations, and the direction of causality should not be assumed. Could it be that better immune functioning, and thus better health, might increase a sense of control?

We must also consider cross-

LOCUS OF CONTROL Differences in perceived sense of control stem from beliefs about where control resides (Rotter, 1966). Someone with an internal locus of control generally feels she is in control of life and its circumstances; she probably believes it is important to take charge and make changes when problems occur. A person with an external locus of control generally feels as if chance, luck, or fate is responsible for her circumstances; there is no point in trying to change things or make them better. Imagine that a doctor tells a patient he needs to change his lifestyle and start exercising. If the patient has an internal locus of control, he will likely take charge and start walking to work or hitting the gym; he expects his actions will impact his health. If the patient has an external locus of control, he is more apt to think his actions won’t make a difference and may not attempt lifestyle changes. In the 1970 British Cohort Study, researchers examined over 11,000 children at age 10, and then assessed their health at age 30. Participants with an internal locus of control, measured at 10 years of age, were less likely as adults to be overweight or obese, and had lower levels of psychological problems. They were also less likely to smoke and more likely to exercise regularly than people with a more external locus of control (Gale, Batty, & Deary, 2008).

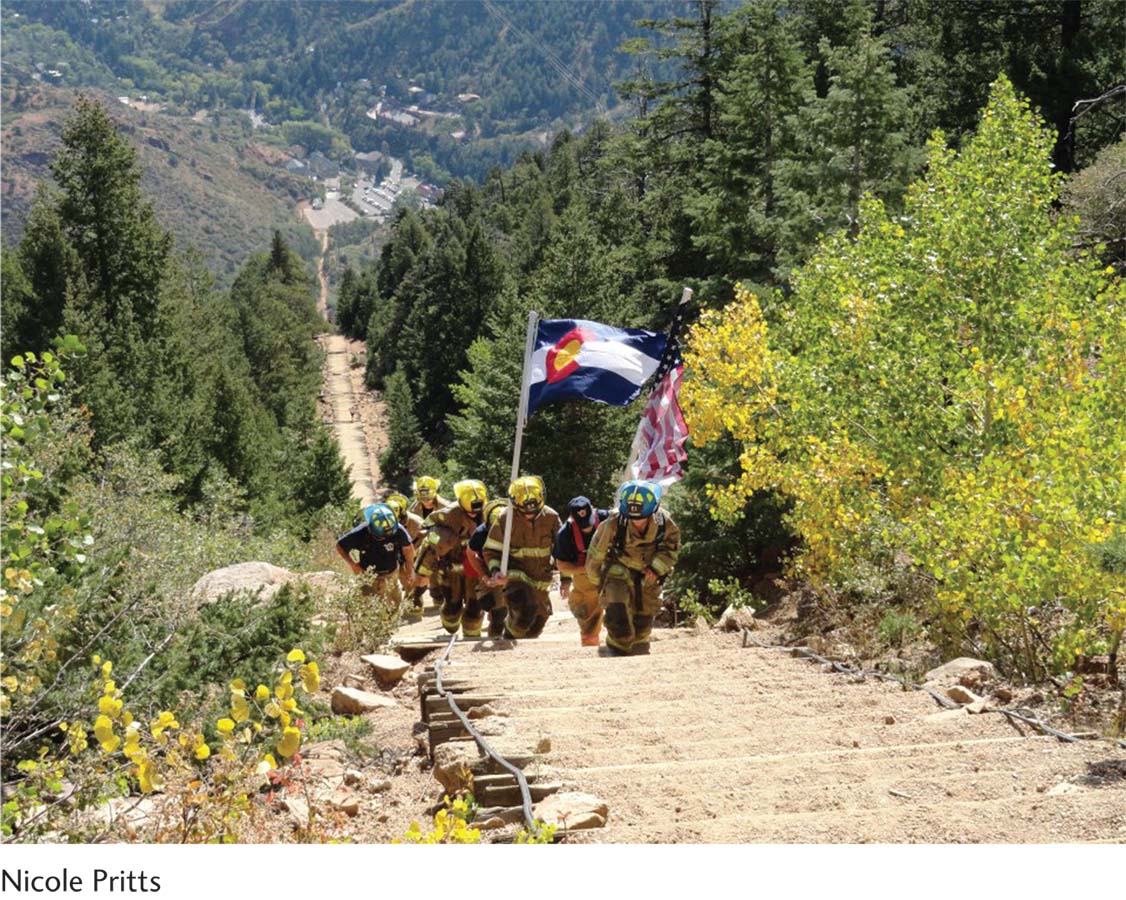

FROM AMBULANCE TO FIREHOUSE Kehlen’s original career goal was to become a firefighter, but jobs are extremely hard to come by in this field. Fresh out of high school, Kehlen joined an ambulance crew with the goal of moving on to the firehouse. Seven years later, he reached his destination. Kehlen is now a firefighter paramedic with the Pueblo Fire Department. His job description still includes performing CPR, inserting breathing tubes, and delivering lifesaving medical care. But now he can also be seen handling fire hoses and rushing into 800-

FROM AMBULANCE TO FIREHOUSE Kehlen’s original career goal was to become a firefighter, but jobs are extremely hard to come by in this field. Fresh out of high school, Kehlen joined an ambulance crew with the goal of moving on to the firehouse. Seven years later, he reached his destination. Kehlen is now a firefighter paramedic with the Pueblo Fire Department. His job description still includes performing CPR, inserting breathing tubes, and delivering lifesaving medical care. But now he can also be seen handling fire hoses and rushing into 800-

Compared to an ambulance, the firehouse environment is far more conducive to managing stress. For starters, there is enormous social support. Fellow firefighters are a lot like family members. They eat together, go to sleep together, and wake to the same flashing lights and tones announcing the latest emergency. “The fire department is such a brotherhood,” Kehlen says. Spending a third of his life at the firehouse with colleagues, Kehlen has come to know and trust them on a deep level. They discuss disturbing events they witness and help each other recover emotionally. “If you don’t talk about it,” says Kehlen, “it’s just going to wear on you.” Another major benefit of working at the firehouse is having the freedom to exercise, which Kehlen considers a major stress reliever. The firefighters are actually required to work out 1 hour per day during their shifts.

Ambulance work is quite another story. Kehlen and his coworkers were friends, but they didn’t share the tight bonds that Kehlen now has with fellow firefighters. And eating healthy and exercising were almost impossible. Ambulance workers don’t have the luxury of making a healthy meal in a kitchen. They often have no choice but to drive to the nearest fast-

Firefighters climb the notoriously difficult “Incline,” a seemingly endless set of stairs up Pikes Peak in Manitou Springs, Colorado. Every year on the morning of September 11, the firefighters walk up the 1-

Tools for Healthy Living

LO 12 Discuss several tools for reducing stress and maintaining health.

Dealing with stressors can be challenging, but you don’t have to grin and bear it. There are many simple ways to manage and reduce stress. Let’s take a look at two powerful stress-

Apply This

Everyday Stress Relievers

You are feeling the pressure. Exam time is here, and you haven’t cracked open a book because you’ve been so busy at work. The holidays are approaching, you have not purchased a single present, and the pile of unpaid bills on your desk is starting to build. With so much to do, you feel paralyzed. In these types of situations, the best solution may be to drop to the floor to do some push-

How does exercise work its magic? Physiologically, we know exercise increases blood flow, activates the autonomic nervous system, and helps initiate the release of several hormones. These physiological reactions help the body defend itself from potential illnesses, especially those that are stress related. Exercise also spurs the release of the body’s natural painkilling and pleasure-

When it comes to choosing an exercise regimen, the tough part is finding an activity that is intense enough to reduce the impact of stress, but sufficiently enjoyable to keep you coming back for more. Research suggests that only 30 minutes of daily exercise is needed to decrease the risk of heart disease, stroke, hypertension, certain types of cancer, and diabetes (Warburton, Charlesworth, Ivey, Nettlefold, & Bredin, 2010) and improve mood (Bryan, Hutchison, Seals, & Allen, 2007; Hansen, Stevens, & Coast, 2001). And exercise needn’t be a chore. Your daily 30 minutes could mean dancing to Just Dance 6 on the Wii, going for a bike ride, raking leaves on a beautiful fall day, or shoveling snow in a winter wonderland.

Exercise is all about getting the body moving, but relaxing the muscles can also relieve stress. “Just relax.” We have heard it said a thousand times, but do we really know how to begin? Physician and physiologist Edmund Jacobson (1938) introduced a technique known as progressive muscle relaxation, which has since been expanded upon. With this technique, you begin by tensing a muscle group (for example, your toes) for about 10 seconds, and then releasing as you focus on the tension leaving. Next you progress to another muscle group, such as the calves, and then the thighs, buttocks, stomach, shoulders, arms, neck, and so on. After several weeks of practice, you will begin to recognize where you hold tension in your muscles—

CONTROVERSIES

Meditate on This

An increasingly popular way to induce relaxation is meditation. If you’ve ever known an anxious person who began meditating regularly, you know that it can have a dramatic “chilling out” effect. A sense of serenity seems to envelop people who take up meditation. But anecdotal evidence or folk wisdom is no substitute for scientific data. What does the research say?

An increasingly popular way to induce relaxation is meditation. If you’ve ever known an anxious person who began meditating regularly, you know that it can have a dramatic “chilling out” effect. A sense of serenity seems to envelop people who take up meditation. But anecdotal evidence or folk wisdom is no substitute for scientific data. What does the research say?

… JUST THINKING MEDITATION IS BENEFICIAL MAY AFFECT THE WAY PEOPLE PERCEIVE AND REPORT ITS EFFECTS.

Numerous studies point to a variety of meditation-

In many cases, it’s unclear whether meditation or some other lifestyle factor such as regular exercise is causing the positive effects researchers have observed. It’s also important to recognize that the expectations of research participants can sway study results in a favorable direction. In other words, just thinking meditation is beneficial may affect the way people perceive and report its effects. Meditation may exert a placebo effect, leading its practitioners to believe that their efforts are paying off. If this is the case, the beliefs (rather than the meditation) are producing the health benefits.

That said, we should point out that long-

Many forms of meditation emphasize control and awareness of breathing. This may be one of the reasons people find meditation so relaxing. Taking slow, deep breaths is a fast and easy way to reduce the impact of stress.

Using a clock or watch to time yourself, breathe in slowly for 5 seconds. Then exhale slowly for 5 seconds. Do this for 1 minute. With each breath, you begin to slow down and relax. The key is to breathe deeply. Draw your breath deep into the diaphragm and avoid shallow, rapid chest breathing.

try this

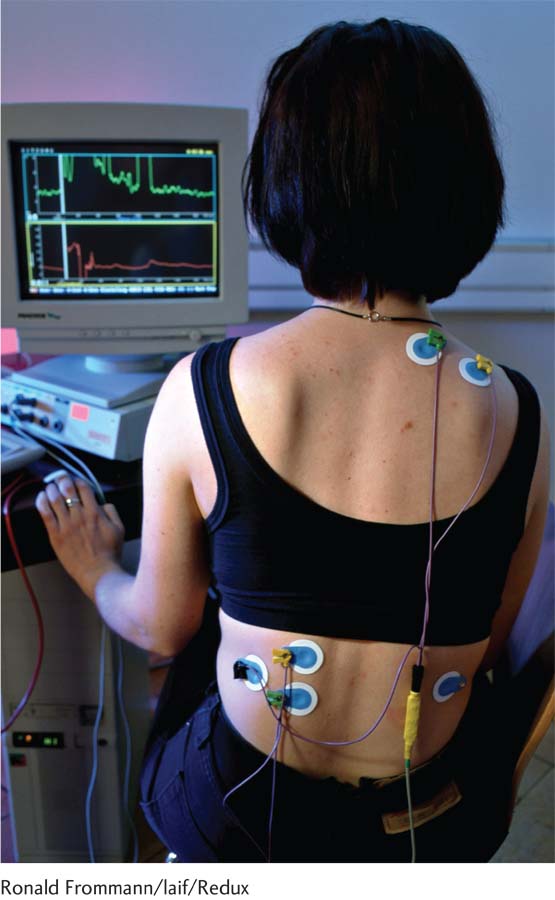

biofeedback A technique that involves providing visual or auditory information about biological processes, allowing a person to control physiological activity (for example, heart rate, blood pressure, and skin temperature).

BIOFEEDBACK A proven method for reducing physiological responses to stressors is biofeedback. This technique builds on learning principles to teach control of seemingly involuntary physiological activity (such as heart rate, blood pressure, and skin temperature). The biofeedback equipment monitors internal responses and provides visual or auditory signals to help a person identify those that are maladaptive (for example, tense shoulder muscles). The person begins by focusing on a signal (a light or tone, for example) that indicates when a desired response occurs. By learning to control this biofeedback indicator, the person learns to maintain the desired response (relaxed shoulders in this example). The goal is to be able to tap into this technique outside of the clinic or lab, and translate what has been learned into real-

A patient at the Max Planck Institute in Munich, Germany, combats back pain using biofeedback, a learning technique that enables a person to manipulate seemingly automatic functions, such as heart rate and blood pressure. With the help of a monitor that signals the occurrence of a target response, a patient can learn how to sustain this response longer.

The use of biofeedback can decrease the frequency of headaches and chronic pain (Flor & Birbaumer, 1993; Sun-

Volunteers in Chongqing, China, celebrate Father’s Day with elderly men in a nursing home. Altruism, or helping others because it feels good, is an excellent stress reliever.

SOCIAL SUPPORT Up until now, we have discussed ways to manage the body’s physiological response to stressors. There are also situational methods to deal with stressors, like maintaining a social support network. Researchers have found that proactively participating in positive enduring relationships with family, friends, and religious groups can generate a health benefit similar to exercise and not smoking (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). People who maintain positive, supportive relationships also have better overall health (Walsh, 2011).

You might expect that receiving support is the key to lowering stress, but research suggests that giving support also really matters. In a study of older married adults, researchers reported reduced mortality rates for participants who indicated that they helped or supported others, including friends, spouses, relatives, and neighbors. There were no reductions in mortality, however, associated with receiving support from others (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003).

Helping others because it gives you pleasure, and expecting nothing in return, is known as altruism, and it appears to be an effective stress reducer and happiness booster (Schwartz, Keyl, Marcum, & Bode, 2009; Schwartz, Meisenhelder, Yunsheng, & Reed, 2003). When we care for others, we generally don’t have time to focus on our own problems; we also come to recognize that others may be dealing with more troubling circumstances than we are.

FAITH, RELIGION, AND PRAYER Psychologists are also discovering the health benefits of faith, religion, and prayer. Research suggests elderly people who actively participate in religious services or pray experience improved health and noticeably lower rates of depression than those who don’t participate in such activities (Lawler-

These various types of proactive, stress-

Apply This

THINK again

Think Positive

In the very first chapter of this book, we introduced a field of study known as positive psychology, “the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, and enabling institutions” (Seligman & Steen, 2005, p. 410). Rather than focusing on mental illness and abnormal behavior, positive psychology emphasizes human strengths and virtues. The goal is well-

In the very first chapter of this book, we introduced a field of study known as positive psychology, “the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, and enabling institutions” (Seligman & Steen, 2005, p. 410). Rather than focusing on mental illness and abnormal behavior, positive psychology emphasizes human strengths and virtues. The goal is well-

… YOUR CURRENT STRESS LEVEL IS WITHIN YOUR CONTROL.

As we wrap up this chapter on stress and health, we encourage you to focus on that third category: flow and happiness in the present moment. No matter what stressors come your way, try to stay grounded in the here and now. The past is the past, the future is uncertain, but this moment is yours. Finding a way to enjoy the present is one of the best ways to reduce stress. We also remind you that your current stress level is very much within your control. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, make time to engage in activities such as exercise and meditation, which produce measurable changes in the body and brain.

TO PROTECT, SERVE, AND NOT GET TOO STRESSED If you’re wondering how Eric Flansburg and Kehlen Kirby are doing these days, both young men are thriving in their careers. Eric joined the police department in Cicero, New York. “I love it,” he says. “Can’t see myself doing anything else.” Recently Eric, his wife, and their two sons (Eric Junior, 6, and Nathan, 2) experienced a major stressor: their home was destroyed in a fire. Thankfully no one was hurt, and the damage was covered by insurance. Something positive actually came out of the crisis: the family emerged stronger and closer than ever.

TO PROTECT, SERVE, AND NOT GET TOO STRESSED If you’re wondering how Eric Flansburg and Kehlen Kirby are doing these days, both young men are thriving in their careers. Eric joined the police department in Cicero, New York. “I love it,” he says. “Can’t see myself doing anything else.” Recently Eric, his wife, and their two sons (Eric Junior, 6, and Nathan, 2) experienced a major stressor: their home was destroyed in a fire. Thankfully no one was hurt, and the damage was covered by insurance. Something positive actually came out of the crisis: the family emerged stronger and closer than ever.

Having worked at the fire station since 2010, Kehlen is really getting into the fire department groove. He was recently promoted to “engineer,” which means he is now responsible for driving the fire engine (in addition to all his firefighting and paramedic responsibilities). When he’s not putting out fires and rescuing people, Kehlen helps his wife run her family medicine practice and cares for his 3-

Having worked at the fire station since 2010, Kehlen is really getting into the fire department groove. He was recently promoted to “engineer,” which means he is now responsible for driving the fire engine (in addition to all his firefighting and paramedic responsibilities). When he’s not putting out fires and rescuing people, Kehlen helps his wife run her family medicine practice and cares for his 3-

show what you know

Question 1

1. Having to choose between two options that are equally attractive to you is called a(n) ____________ conflict.

approach–

Question 2

2. ____________ is apparent when a person deals directly with a problem by attempting to solve it.

Emotion-

focused coping Positive psychology

Support seeking

Problem-

focused coping

d. Problem-

Question 3

3. Individuals who are more relaxed, patient, and nonaggressive are considered to have a:

Type A personality.

Type B personality.

Type C personality.

Type D personality.

b. Type B personality.

Question 4

4. Describe three “tools” for healthy living that you could use to improve your health.

Answers may vary. Stress management incorporates tools to lower the impact of possible stressors. Exercise, meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback, and social support all have positive physical and psychological effects on the response to stressors. In addition, looking out for the well-