14.1 An Introduction to Social Psychology

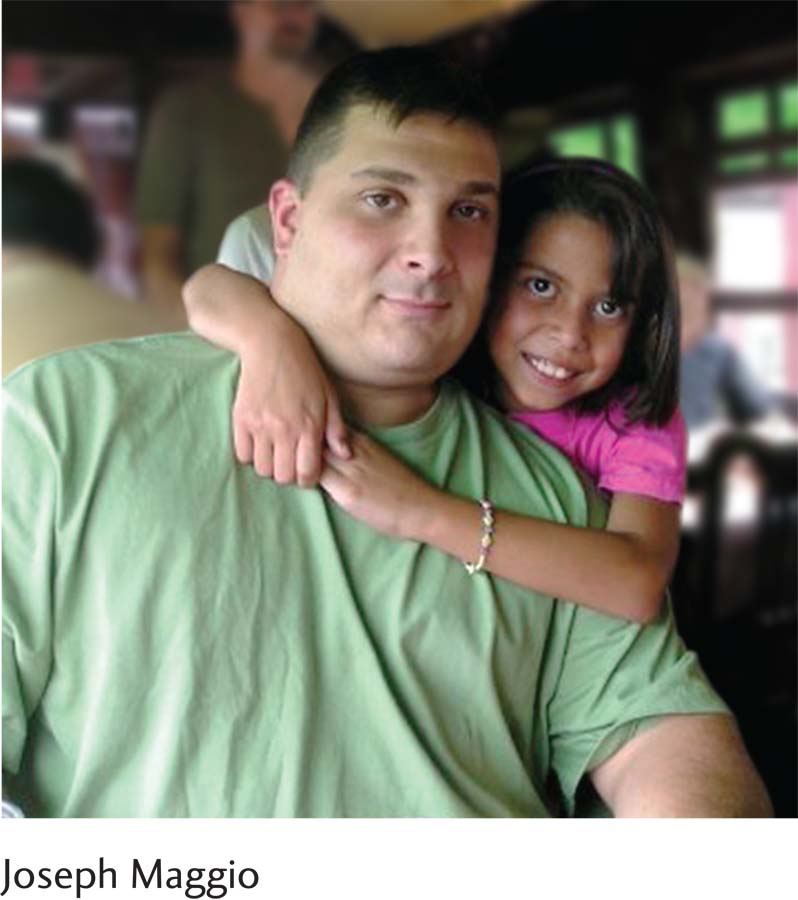

LOVE STORY Prior to 2006, Joe Maggio did not have a fulfilling love life. While serving overseas in the military, he had a relationship with a local woman with whom he was not at all compatible. But something beautiful came out of their failed union: a baby girl named Kristina. Joe was awarded full custody, and he returned to Long Island, New York, to begin his life as a single dad. In between work and taking care of his daughter, there was little time for dating. Joe was not the type to frequent bars and nightclubs, and his work as an ice cream truck driver provided few opportunities for meeting other singles. It never seemed to work out with the girlfriends he did manage to date. And as Joe admits, “I had my share of doozies [extraordinarily bad experiences].”

Everything abruptly changed when Susanne entered the picture. Their first face-

Before joining Match.com, Joe Maggio was a single father to daughter Kristina. Dating was a challenge, as most of the women Joe met lacked the qualities he desired. Then, with a few clicks and keystrokes, along came Susanne . . .

Instantly at ease, Susanne sat down and began to talk with Joe and Kristina. “It was just kind of relaxed . . . like we had known each other forever,” says Susanne, who at 32 was finished playing games and exploring dead-

The next morning, Joe called Susanne and invited her for a cup of coffee. “We did not leave the local Starbucks until almost seven, eight hours later,” he recalls. During that marathon date, Joe and Susanne shared stories about their families and talked about their hopes and dreams. “I didn’t want the day to end,” says Joe, who then invited Susanne home and made her a dinner of sautéed pork chops, roasted peppers, and potatoes. “I think I kind of won her heart that night.”

Joe and Susanne’s initial impressions of one another were right on. They were extremely compatible people with similar backgrounds and family values. Both were big fans of cooking, baseball (the Mets), and spending Friday night curled up on the couch watching a movie. Susanne found it attractive that Joe was a single father. And Joe came to love how Susanne treated Kristina like her own daughter, and how Kristina loved her back. You might say Joe and Susanne were perfectly matched. How did they find one another?

Note: Quotations attributed to Julius Achon and Joe and Susanne Maggio are personal communications.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LO 1 Define social psychology and identify how it is different from sociology.

LO 2 Describe social cognition and how we use attributions to explain behavior.

LO 3 Describe how attributions lead to mistakes in our explanations for behaviors.

LO 4 Describe social influence and recognize the factors associated with persuasion.

LO 5 Define compliance and explain some of the techniques used to gain it.

LO 6 Identify the factors that influence the likelihood of someone conforming.

LO 7 Describe obedience and explain how Stanley Milgram studied it.

LO 8 Recognize the circumstances that influence the occurrence of the bystander effect.

LO 9 Demonstrate an understanding of aggression and identify some of its causes.

LO 10 Recognize how group affiliation influences the development of stereotypes.

LO 11 Compare prosocial behavior and altruism.

LO 12 Identify the three major factors contributing to interpersonal attraction.

What Is Social Psychology?

Joe and Susanne did not meet at a church, a library, or a bar. They did not work in the same office, nor were they introduced by mutual friends. Like a growing number of couples, Joe and Susanne first encountered one another online. They met through Match.com, the popular dating Web site.

In the mid-

In just two decades, online dating has gone from being essentially nonexistent to a primary avenue for finding love (Figure 14.1). Research suggests that the Internet is the second most common way to connect with a potential partner, the first being an introduction by mutual friends (Finkel, Eastwick, Karney, Reis, & Sprecher, 2012). Joe and Susanne met through one of the mainstream online dating services, but there are also highly specialized sites and mobile apps to accommodate particular interests. Looking for a vegetarian mate? Try VeggieDate.org. Searching for a farmer to love? Visit FarmersOnly.com. There are even digital services designed to match people with the same book preferences and food allergies.

Online dating has forever changed the singles’ landscape. What other medium allows you to scan and research a database of thousands, if not millions, of potential partners from the comfort of your sofa, or filter potential mates with the ease of a finger swipe? Online dating has also created a new laboratory for psychologists to study the way people’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are influenced by others. Put differently, it is an emerging topic of research in social psychology.

LO 1 Define social psychology and identify how it is different from sociology.

In every chapter of this book, we have touched on issues relevant to social psychology. Chapter 1, for example, tells the story of 33 Chilean miners trapped in a sweltering, underground hole for more than 2 months. How do you think the social interactions among these men influenced their behaviors, thoughts, and feelings? In Chapter 3, we journeyed into the world of Zoe, Emma, and Sophie, identical triplets who are deaf and blind. How might the triplets’ social behaviors differ from those of children with normal hearing and vision? Then there was Clive Wearing from Chapter 6. How do you suppose Clive’s devastating memory loss affects his relationships? Social psychologists strive to answer these types of questions.

social psychology The study of human cognition, emotion, and behavior in relation to others, including how people behave in social settings.

Social psychology is the study of human cognition, emotion, and behavior in relation to others. Students often ask how social psychology differs from the field of sociology. The answer is simple: Social psychology explores the way individuals behave in relation to others and groups, while sociology examines the groups themselves—

Research Methods in Social Psychology

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described how participants’ and researchers’ expectations can influence the results of an experiment. One form of deception used to counter this is the double-

Social psychologists use the same general research methods as other psychologists, but often with an added twist of deception. Deception is sometimes necessary because people do not always behave naturally when they know they are being observed. Some participants try to conform to expectations; others do just the opposite, behaving in ways they believe will contradict the researchers’ predictions. Suppose a team of researchers is studying facial expressions in social settings. If participants know that every glance and grimace is being analyzed, they may feel self-

Social psychology studies often involve confederates, who are people secretly working for the researchers. Playing the role of participants, experimenters, or simply bystanders, confederates say what the researchers tell them to say and do what the researchers tell them to do. They are, unknown to the other participants, just part of the researchers’ experimental manipulation.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed informed consent and debriefing. Debriefing is an ethical component of disclosure in which researchers provide participants with useful information related to the study. In some cases, participants are informed of deception or manipulation they were exposed to in the study—

In most cases, the deception is not kept secret forever. Researchers debrief their participants at the end of a study, or review aspects of the research initially kept under wraps. Even after learning they were deceived, many participants report they are willing to take part in subsequent psychology experiments (Blatchley & O’Brien, 2007). Debriefing is also a time when researchers make sure that participants were not harmed or upset by their involvement in a study. We should note that all psychology research affiliated with colleges and universities must be approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure that no harm will come from participation. This requirement is partly a reaction to early studies involving extreme deception and manipulation—

A research confederate in Stanley Milgram’s classic experiment is strapped to a table and hooked up to electrodes. Participants in this study were led to believe they were administering electrical shocks to the confederate when in reality the confederate was just pretending to be shocked. This allowed the researchers to study how far participants would go applying shocks—

show what you know

Question 1

1. ____________ studies individuals in relation to others and groups, whereas ____________ studies the groups themselves, including cultures and societies.

Sociology; social psychology

Social psychology; sociology

Sociology; a confederate

A confederate; social psychology

b. Social psychology; sociology

Question 2

2. When a participant has completed his involvement in a research project, generally the researcher will ____________ him by discussing aspects of the study previously kept secret and making sure he was not upset or harmed by his involvement.

debrief

Question 3

3. Social psychology research occasionally involves some form of deception that includes a confederate. How is this type of deception different from the use of double-

Social psychology studies often involve confederates, who are people secretly working for the researchers. Playing the role of participants, confederates say what the researchers tell them to say and do what the researchers tell them to do. They are, unknown to the other participants, just part of the researchers’ experimental manipulation. In a double-