14.3 Social Influence

11 ORPHANS In 1983 a 7-

11 ORPHANS In 1983 a 7-

Julius was born on December 12, 1976, in Awake, a village that had no electricity or running water. “Life in Uganda is very tough,” says Julius, who spent his childhood sleeping between eight brothers and sisters on the floor of a one-

A group of women sit together in Awake, Uganda, the village where Julius Achon was born and raised. Day-

After coming home, Julius began to run competitively. Running made him feel free, and running was his great gift. He ran 42 miles barefoot to his first major track meet in the city of Lira. Hours after arriving, Julius was racing—

Julius wins the 1,500 meters at the 2005 Payton Jordan U.S. Open at Stanford University. With two Olympics under his belt, the young runner had enjoyed an extremely successful athletic career, but his focus was beginning to shift onto something bigger—

As awe-

“Where are your parents?” Julius remembers asking. One of the children said their parents had been shot and killed. “Can I walk you to my home, you know, to go eat?” Julius asked. The children eagerly agreed and followed him home for a meal of rice, beans, and porridge. What happened next may seem unbelievable, but Julius and his family are extraordinary people. Julius asked his father to shelter the 11 orphans, provided that he, Julius, would send money home to cover their living expenses. Julius had been running with a professional team in Portugal, making about $5,000 a year, not even enough to cover his own expenses. His parents already had six people living in their one-

“Ah, it’s no problem,” said Julius’ father. And just like that, Julius and his family adopted 11 children.

Power of Others

Throughout the years Julius was trotting the globe and winning medals, he never forgot about Uganda. He remembered the people back home with empty stomachs and no access to lifesaving medicine, living in constant fear of the LRA. Julius was raised in a family that had always reached out to neighbors in need. “You will get help from other people when you do good,” his parents used to say. Julius also felt blessed by all the support people outside the family had given him. “I feel I was so loved [by] others,” says Julius, referring to the mentors and coaches who had provided him with places to stay, clothes to wear, and family away from home.

So when Julius encountered those 11 orphans lying under the bus, he didn’t think twice about coming to their rescue. His decision to bring them into his life probably had something to do with the positive interactions he had experienced with people in his past.

LO 4 Describe social influence and recognize the factors associated with persuasion.

social influence How a person is affected by others as evidenced in behaviors, emotions, and cognition.

Children tend to perform better in school when teachers expect them to succeed (Rosenthal, 2002a). This is especially true for students who are young and socioeconomically disadvantaged (Sorhagen, 2013).

SOCIAL INFLUENCE DEFINED Rarely a day goes by that we do not come into contact with other human beings. This contact may be up close and personal, in a family or a tight-

EXPECTATIONS Think back to your days in elementary school. What kind of student were you—

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we discussed how poverty and its associated stressors can have a lasting impact on the development of the brain and subsequent cognitive abilities. Some factors that influence children’s brain development include nutrition, toxins, and abuse. Here, we see that the expectations of others can impact cognitive functioning as well.

Expectations can have a powerful impact on behaviors. Here, we have a case in which teachers’ expectations (based on false information) seemed to transform students’ aptitudes and facilitate substantial gains. Let’s consider the types of teacher behaviors that could explain this effect. The teachers may have inadvertently communicated expectations by demonstrating “warmer socioemotional” attitudes toward the “surprising gain” students; they may have provided them with more material and opportunities to respond to high expectations; and they may have given them more complex and personalized feedback (Rosenthal, 2002a, 2003). From the student’s perspective, teacher behaviors can create a desire to work hard, or they can result in a decline in interest and confidence (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2011).

Since this classic study was conducted approximately 50 years ago, researchers have studied expectations in a variety of classroom settings. Their results demonstrate that teacher expectations do not have the same effect or degree of impact on all students (Jussim & Harber, 2005). They appear to have greater influence on younger students (first and second graders) and children of lower socioeconomic status (Sorhagen, 2013).

Expectations are powerful, but they are just one form of social influence. Let’s return to the story of Julius and learn about more targeted types of influence.

Persuasion

persuasion Intentionally trying to make people change their attitudes and beliefs, which may lead to changes in their behaviors.

When Julius asked his father to shelter and feed the 11 orphans, he was using a form of social influence called persuasion. With persuasion, one intentionally tries to make other people change their attitudes and beliefs, which may (or may not) lead to changes in their behaviors. The person doing the persuading does not necessarily have control over those he seeks to persuade. Julius could not force his father to feel sympathy for the orphans. His father made a choice.

The important elements of persuasion were first described by Carl Hovland, a social psychologist who studied the morale of soldiers fighting in World War II. According to Hovland, three factors determine persuasive power: the source, the message, and the audience (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953).

THE SOURCE The credibility of the person or organization sending a message is critical, and credibility can be dependent on perceived expertise and trustworthiness (Hovland & Weiss, 1951). Suppose you are searching for information about the risks associated with vaccines—

THE MESSAGE The content of the message also determines persuasive power. One important factor is the degree to which the message is logical and to the point (Chaiken & Eagly, 1976). Fear-

THE AUDIENCE Finally, we turn to the characteristics of the audience. One important factor is age. For example, middle-

ELABORATION LIKELIHOOD MODEL The elaboration likelihood model proposes that persuasion hinges on the way people think about an argument, and it can occur via one of two pathways. With the central route to persuasion, the focus is on the content of the message, and thinking critically about it. With the peripheral route, the focus is not on the content but on “extramessage factors” such as the credibility or attractiveness of the source (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Little critical thinking is involved, and the commitment to the outcome is low. How do we know which route the message will take? If the person receiving the message is knowledgeable and invested in its outcome, the central route to persuasion is used. If the person is distracted, lacks knowledge about the topic, or does not feel invested in the outcome, the peripheral route is typically taken (O’Keefe, 2008).

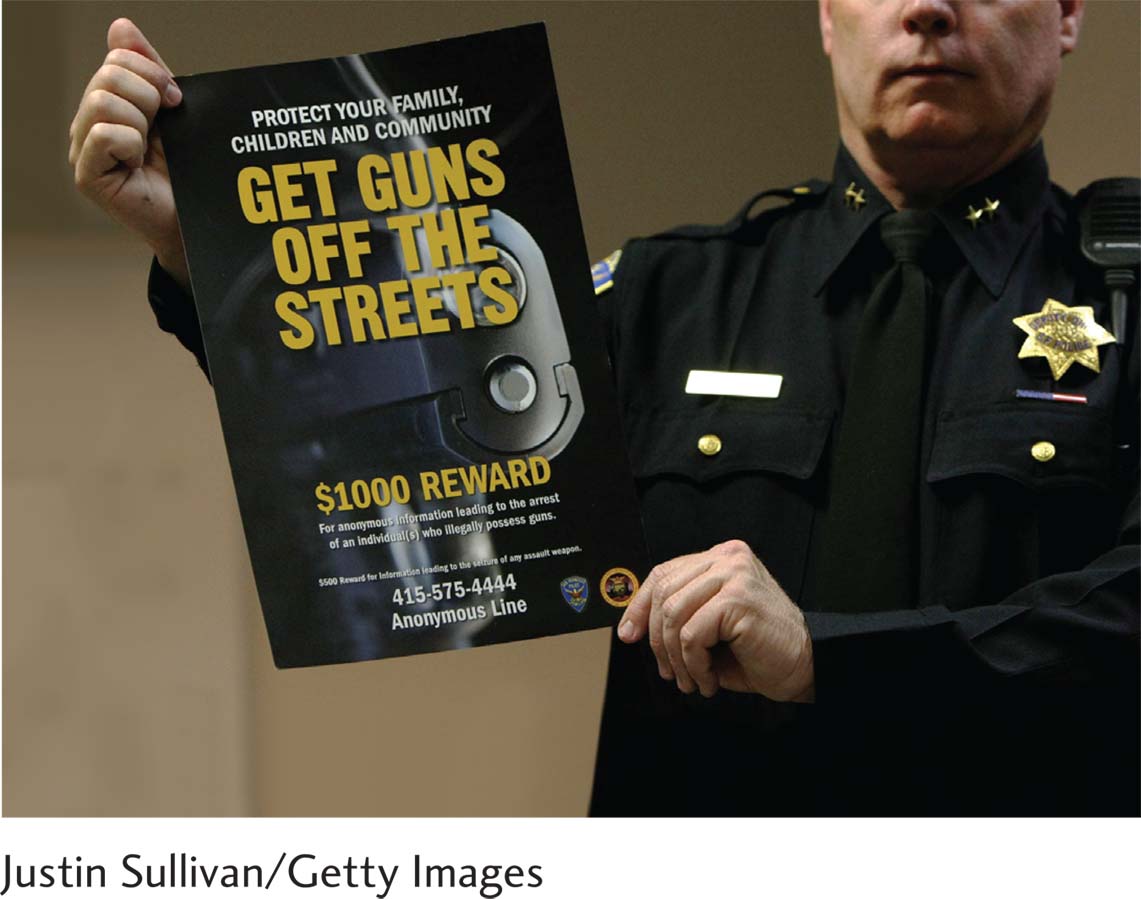

The fact that this anti-

Immediately following the tragic Newtown massacre of 2012, there was an upsurge in calls for tighter gun control in the United States. Someone with strong feelings about gun control (either for or against it) would likely take advantage of central processing when trying to develop a persuasive argument. Some politicians, for example, tried to persuade others by supplying data about the number of gun-

The take-

Compliance

LO 5 Define compliance and explain some of the techniques used to gain it.

compliance Changes in behavior at the request or direction of another person or group, who in general do not have any true authority.

The results of persuasion are internal and related to a change in attitude (Key, Edlund, Sagarin, & Bizer, 2009). Compliance, on the other hand, occurs when someone voluntarily changes her behavior at the request or direction of another person or group, who in general does not have any true authority over her. Compliance is evident in changes to “overt behavior” (Key et al., 2009). For example, if you want to get someone to help clean up after a party, you would try to get him to comply with your request, perhaps through some mild form of guilt (Remember the last party we had, when I helped you?).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 4, we discussed the automatic cognitive activity that guides some behaviors. These behaviors appear to occur without our intent or awareness. Compliance can be driven by automatic processes.

Surprisingly, compliance often occurs outside of our awareness. Think of an everyday situation in which you mindlessly comply with another person’s request. You’re waiting in line at the copy machine, and a man asks if he can cut in front of you. Do you allow it? Your response may depend on the wording of the request. Researchers studying this very scenario—

foot-

As you can see, compliance can be associated with mindlessness. Understanding this might lead you to reflect on how compliance comes into play in everyday situations (Fennis & Janssen, 2010). For example, salespeople and marketing experts use a variety of techniques to get consumers to comply with their requests. One common method is the foot-

Looks like this petitioner has gotten her “foot in the door,” so to speak. With the foot-

The reasoning is that if you have already said yes to a small request, chances are you will agree to a bigger request to remain consistent in your involvement. Your prior participation leads you to believe you are the type of person who gets involved; in other words, your attitude has shifted (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Freedman & Fraser, 1966). So why is such a strategy called foot-

door-

Another method for gaining compliance is the door-

Let’s review these concepts using Julius as an example. After meeting the 11 orphans, Julius brought them home and asked his parents to provide them with a meal. Once his parents complied with this initial request, Julius made a much larger request—

Compliance generally occurs in response to specific requests or instructions: Will you pick up the kids after school? Can you chop these onions? Please collect your sweaty socks from the bathroom floor! But social influence needn’t be explicit. Sometimes we adapt our behaviors and beliefs simply to fit in with the crowd.

Conformity

When Julius came to the United States on a college scholarship in 1995, he was struck by some of the cultural differences he observed between the United States and Uganda—

During the decade Julius lived in the United States, he never stopped acting like a Ugandan. Before going out in the evening, he would tuck in his shirt, check his hair, and make sure his clothes were ironed—

LO 6 Identify the factors that influence the likelihood of someone conforming.

conformity The urge to modify behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions to match those of others.

norms Standards of the social environment.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we described Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which includes the need to belong. If physiological and safety needs are met, an individual will be motivated by the need for love and belongingness. This need can drive us to conform.

FOLLOWING THE CROWD Have you ever found yourself turning to look in the same direction as other people who are staring at something, just because you see them doing so? During the Waldo Canyon Fires in Colorado Springs in the summer of 2012, a day did not pass without people pointing to the mountain range. It was next to impossible to avoid looking in the direction they were pointing, and not just because of the smoke coming from the mountains. We seem to have a commanding urge to do what others are doing, even if it means changing our normal behavior. This tendency to modify our behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions to match those of others is known as conformity. Sometimes we conform to the norms or standards of the social environment, such as the group to which we are connected. Unlike compliance, which occurs in response to an explicit and direct request, conformity is generally unspoken. We often conform because we feel compelled to fit in and belong.

It is important to note that conformity is not always a bad thing. We rely on conformity in many cases to ensure the smooth running of day-

The next time you are outside in a fairly crowded area, look up and keep your eyes toward the sky. You will find that some people change their gazes to match yours, even though there is no other indication that something is happening above.

try this

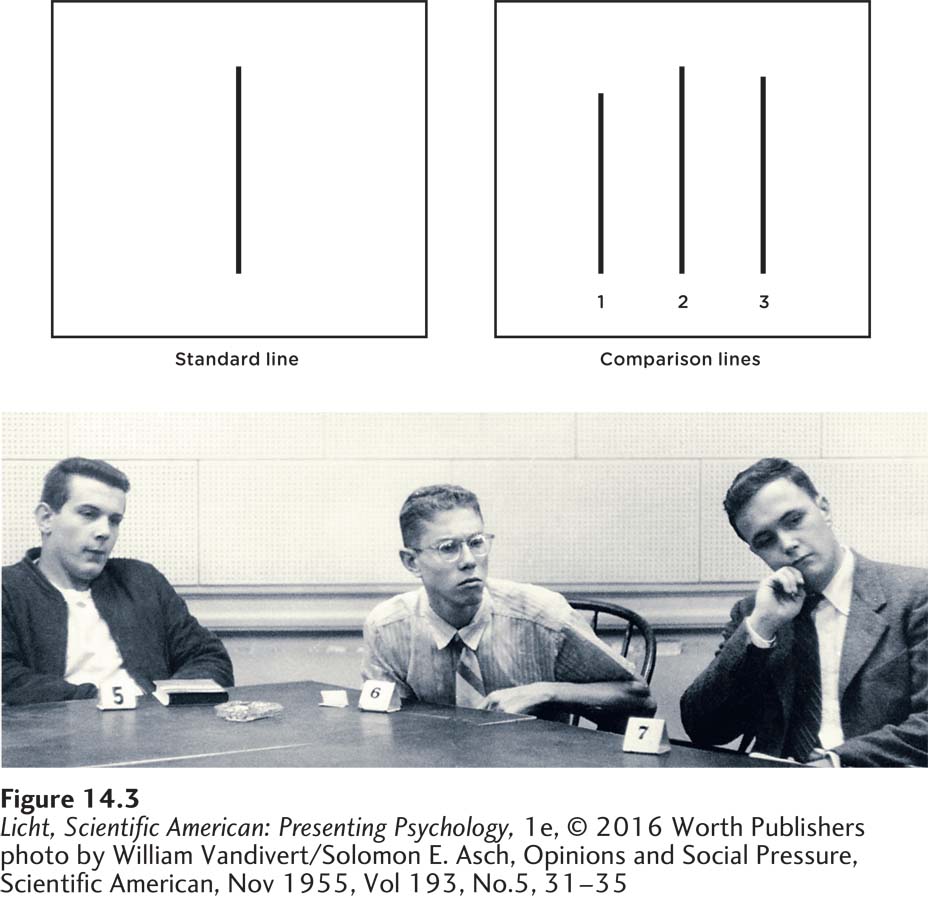

STUDYING CONFORMITY Social psychologists have studied conformity in a variety of settings, including American colleges. In a classic experiment by Solomon Asch (1955), college-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we explained that a control group in an experiment is not exposed to the treatment variable. In this case, the control group is not exposed to the confederates making incorrect answers.

Would the real participant (the sixth person to answer) follow suit and conform to the wrong answer, or would he stand his ground and report the correct answer? In roughly 37% of these trials, participants went along with the group and provided the incorrect answer. What’s more, 76% of the participants conformed to the incorrect answers of the confederates at least once (Asch, 1955, 1956). When members of the control group made the same judgments alone in a room, they were correct 99% of the time, confirming that the differences between the standard line and the comparison lines were substantial, and generally not difficult to assess. It is worth noting that most participants (95%) refused to conform on at least one occasion, choosing an answer that conflicted with that of the group (Asch, 1956; Griggs, 2015). Thus, they were capable of thinking and behaving independently. This type of study was later replicated in a variety of cultures, with mostly similar results (Bond & Smith, 1996).

Participants in this experiment were asked to look at the lines on two cards, announcing which of the comparison lines was closest in length to the standard line. Imagine you are a participant, like the man wearing glasses in this photo, and everyone else at the table chooses Line 3. Would that influence your answer? If you are like many participants, it would. Seventy-

WHY CONFORM? People do not always conform to the behavior of others, but what factors come into play when they do? There are three major reasons for conformity. Most of us want the approval of others, to be liked and accepted. This desire influences our behavior and is known as normative social influence. Just think back to middle school—

Listed below are certain conditions that increase the likelihood of conforming (Aronson, 2012; Asch, 1955):

The group includes at least three other people who are unanimous.

You have to report your decision in front of others and give your reasons.

You are faced with a task you think is difficult.

You are unsure of your ability to perform a task.

And here are some conditions that decrease the likelihood of conforming:

At least one other person is going against the group with you (Asch, 1955).

Group members come from individualist, or “me-

centered” cultures, meaning they are less likely to conform than those from collectivistic, or community- centered, cultures (Bond & Smith, 1996).

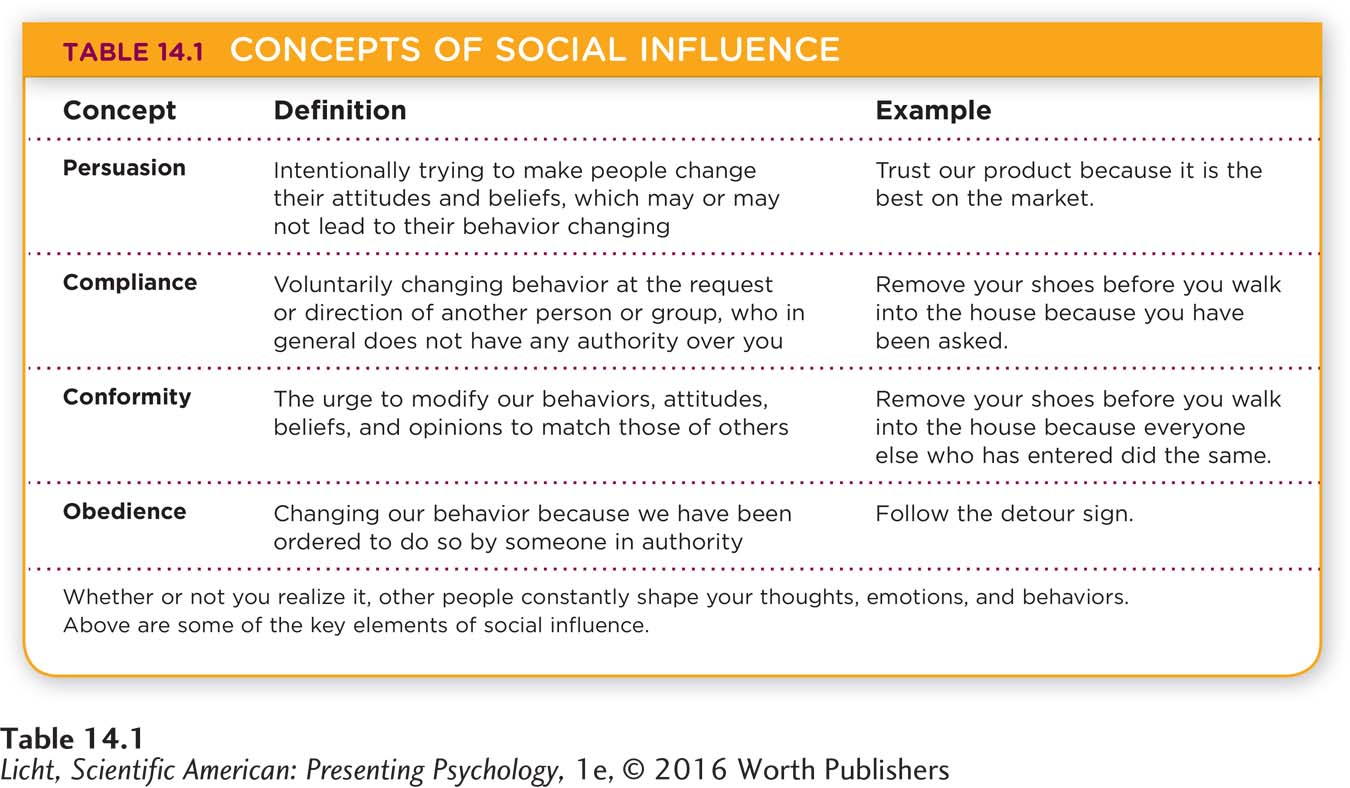

When you conform, no one is specifically telling you to do so. But this is not the case with all types of social influence (Table 14.1). Let’s take a trip to the darker side and explore the frightening phenomenon of obedience.

Obedience

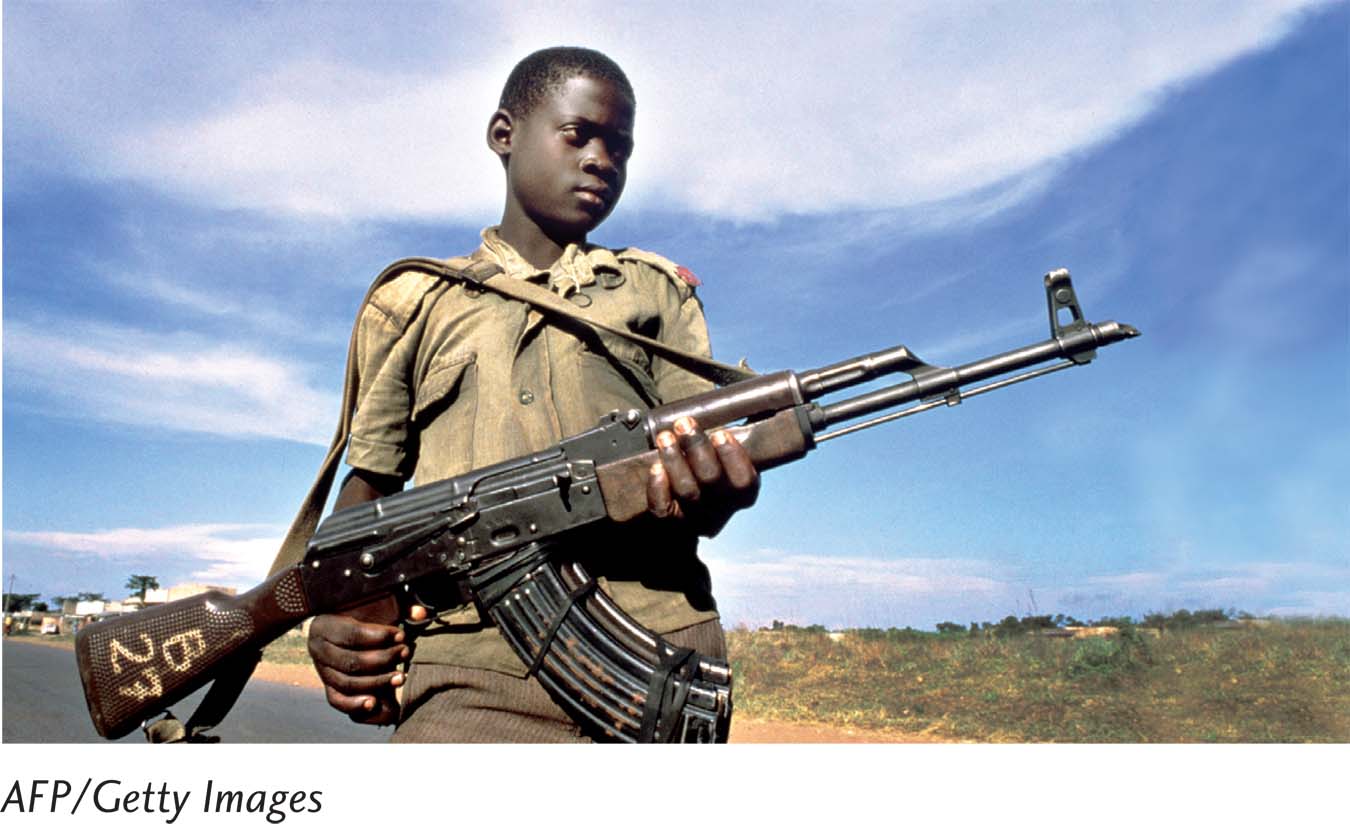

A young boy wields a Kalashnikov rifle near Kampala, Uganda. He is among the tens of thousands of children who have been exploited by military groups in Uganda. Julius was just 12 years old when he was abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and forced to fight and plunder on the group’s behalf.

BOY SOLDIERS During Uganda’s 2-

BOY SOLDIERS During Uganda’s 2-

While a captive of the LRA, Julius witnessed other boy soldiers assaulting innocent people and stealing property. Sometimes at the end of the day, they would laugh or brag about how many people they had beaten or killed. But these were just “normal” boys from the villages, children who never would have behaved this way under regular circumstances. And some showed clear signs of regret. Julius remembers seeing other child soldiers cry alone at night after returning to the camp when there was time to reflect on what they had done.

How do you explain this tragedy? What drives an ordinary child to commit senseless violence? A psychologist might tell you it has something to do with obedience.

LO 7 Describe obedience and explain how Stanley Milgram studied it.

obedience Changing behavior because we have been ordered to do so by an authority figure.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 13, we introduced the concept of transference, a reaction some clients have to their therapists. A client demonstrating transference responds to the therapist as if dealing with a parent, or other important caregiver from childhood; this may include behaving more childlike and obedient.

One of the most disconcerting results of social influence is obedience, which occurs when we change our behavior, or act in a way we might not normally act, because we have been ordered to do so by an authority figure. In these situations, an imbalance of power exists, and the person with more power (for example, a teacher, police officer, doctor, or boss) generally has an advantage over someone with less power, who is more likely to be obedient out of respect, fear, or concern. In some cases, the person in charge demands obedience for the well-

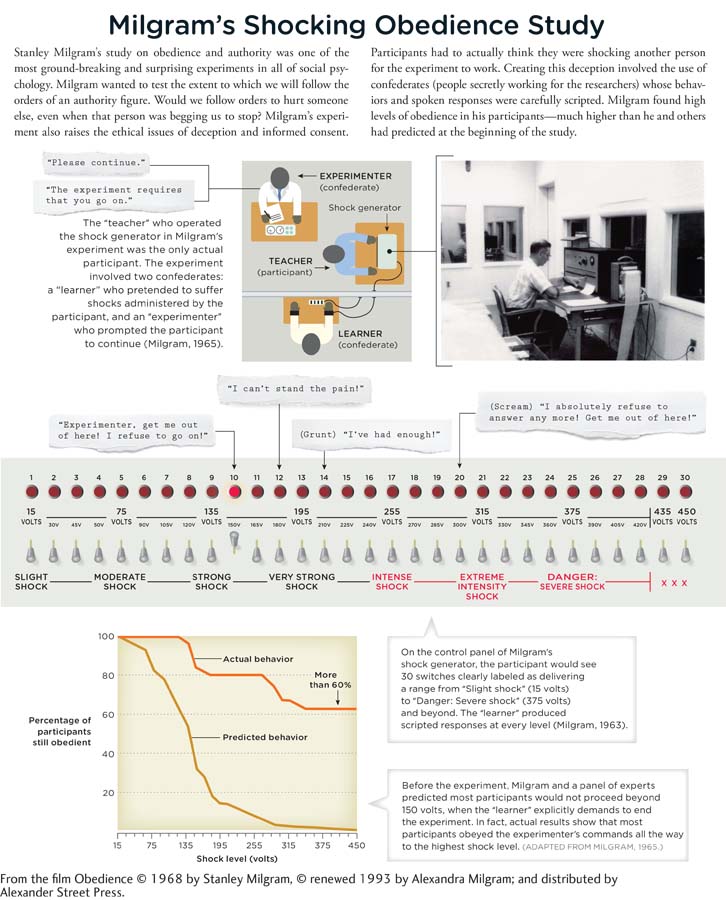

THIS WILL SHOCK YOU: MILGRAM’S STUDY Back in the 1960s, psychologist Stanley Milgram was interested in determining the extent to which obedience can lead to behaviors that most people would consider unethical. Milgram (1963, 1974) conducted a series of experiments examining how far people would go, particularly in terms of punishing others, when urged to do so by an authority figure. Participants were told the study was about memory and learning (another example of research deception). The sample included teachers, salespeople, post office workers, engineers, and laborers, representing a wide range of educational backgrounds, from elementary school dropouts to people with graduate degrees.

Upon arriving at the Yale University laboratory, participants were informed they would be using punishment as part of a learning experiment. They were then asked to draw a slip of paper from a hat; the slip told them they had been randomly assigned the teacher role, although the truth was that a confederate always played the role of the learner (the hat contained two slips that both read “teacher”). To start, the teacher was asked to sit in the learner’s chair, so that he could experience a 45-

INFOGRAPHIC 14.2

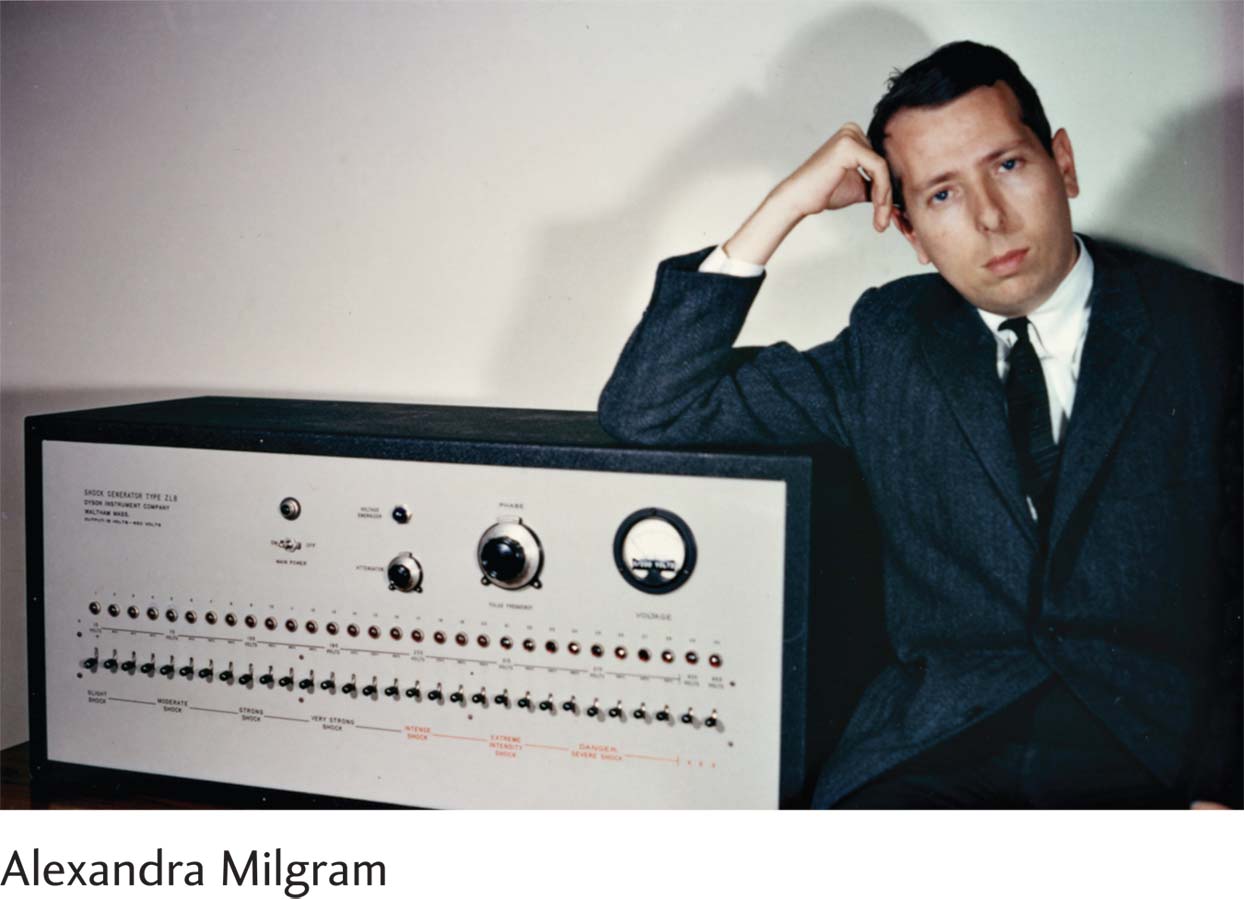

A photo of psychologist Stanley Milgram appears on the cover of his biography, The Man Who Shocked The World: The Life and Legacy of Stanley Milgram (2004), by Thomas Blass. Milgram’s research illuminated the dangers of human obedience. Feeling pressure from authority figures, participants in Milgram’s studies were willing to administer what they believed to be painful and life-

The learner (the confederate) did not receive actual shocks, but instead had a script of responses he was to make as the experiment continued. The learner’s behaviors, including the mistakes he made and his responses to the increasing shock levels (including mild complaints, screaming, references to his heart condition, pleas for the experiment to stop, and total silence as if he were unconscious or even dead), were identical for all participants. A researcher in a white lab coat (also a confederate with scripted responses) always remained in the room with the teacher, and he was insistent that the experiment proceed if the teacher began to question going any further given the learner’s responses (such as “Experimenter, get me out of here. . . . I refuse to go on” or “I can’t stand the pain”; Milgram, 1965, p. 62). The researcher would say to the teacher, “Please continue” and “You have no other choice, you must go on” (Milgram, 1963, p. 374).

How many teachers do you think obeyed the researcher and proceeded with the experiment in spite of the learner’s desperate pleas? Before the experiment, Milgram asked a variety of people (including psychiatrists and students) to predict how many teachers would obey the researcher. Many believed that the participants would refuse to continue at some point in the experiment. Most of the psychiatrists, for example, predicted that only 0.125% of participants would continue to the highest voltage (Milgram, 1965). They also guessed that the majority of the participants would quit the experiment when the learner began his protests.

Here’s what actually happened: 65% of participants continued to the highest voltage level. Most of these participants were obviously not comfortable with what they were doing (stuttering, sweating, trembling), yet they continued. Even those who eventually refused to proceed went much further than anyone (even Milgram himself) had predicted—

We should emphasize that participants were not necessarily comfortable with their role as teachers. One person who witnessed the study reported the following:

I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse. . . . At one point he pushed his fist into his forehead and muttered: “Oh God, let’s stop it.” And yet he continued to respond to every word of the experimenter, and obeyed to the end (Milgram, 1963, p. 377).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we reported that professional organizations have specific guidelines to ensure ethical treatment of research participants. They include doing no harm, safeguarding welfare, and respecting human dignity. An Institutional Review Board also ensures the well-

REPLICATING MILGRAM This type of research has been replicated in the United States and in other countries, and the findings have remained fairly consistent, with 61–

Milgram and others have followed up on the original study, to determine if there were specific factors or characteristics that made it more likely someone would be obedient in this type of scenario (Blass, 1991; Burger, 2009; Milgram, 1965). Several key factors determined whether participants were obedient in these studies: (1) the legitimacy of the authority figure (the more legitimate, the more obedience demonstrated by participants); (2) the closeness of the authority figure (the closer the experimenter was to participants, the higher their level of obedience); (3) the closeness of the learner (the closer the learner, the less obedient the participant); and (4) the presence of other teachers (if another confederate was acting as an obedient teacher, the participant was more likely to obey as well).

Milgram’s initial motivation for studying obedience came from learning about the horrific events of World War II and the Holocaust, which “could only have been carried out on a massive scale if a very large number of people obeyed orders” (Milgram, 1974, p. 1). And his experiments on obedience seem to support this suggestion. One ray of hope did shine through in his later experiments, and that was how participants responded when they saw others refuse to obey. In one follow-

show what you know

Question 1

1. Match the definitions with the terms:

how a person is affected by others

intentionally trying to make people change their attitudes

a person voluntarily changes behavior at the request of someone without authority

someone asks for a small request, followed by a larger request

the urge to modify behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs to match those of others

| ______ conformity | ______ persuasion |

| ______compliance | ______foot- |

| ______social influence |

a. social influence; b. persuasion; c. compliance; d. foot-

Question 2

2. ____________ occurs when we change our behavior, or act in a way we might not normally, because we have been ordered to do so by an authority figure.

Persuasion

Compliance

Conformity

Obedience

d. Obedience

Question 3

3. Asch’s experiments with conformity show how difficult it is to resist the urge to conform to the behaviors, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions of others. At the same time, many of his participants did not cave in to so-

Answers will vary. Examples may include resisting the urge to eat dessert when others at the table are doing so, saying no to a cigarette when others offer one, and so forth.