14.4 Groups and Aggression

Sometimes other “people” don’t have to be present and watching for social facilitation to work. Researchers have demonstrated that competitive seniors pedal harder on stationary bikes when they have an avatar rival to race against (Anderson-

Thus far, the primary focus of this chapter has been people in social situations. We learned, for example, how individuals process information about other people (social cognition) and how behavior is shaped by social interactions (social influence). But human beings do not exist solely as isolated units. When striving toward a common goal, we often come together in groups, and these groups have their own fascinating social dynamics.

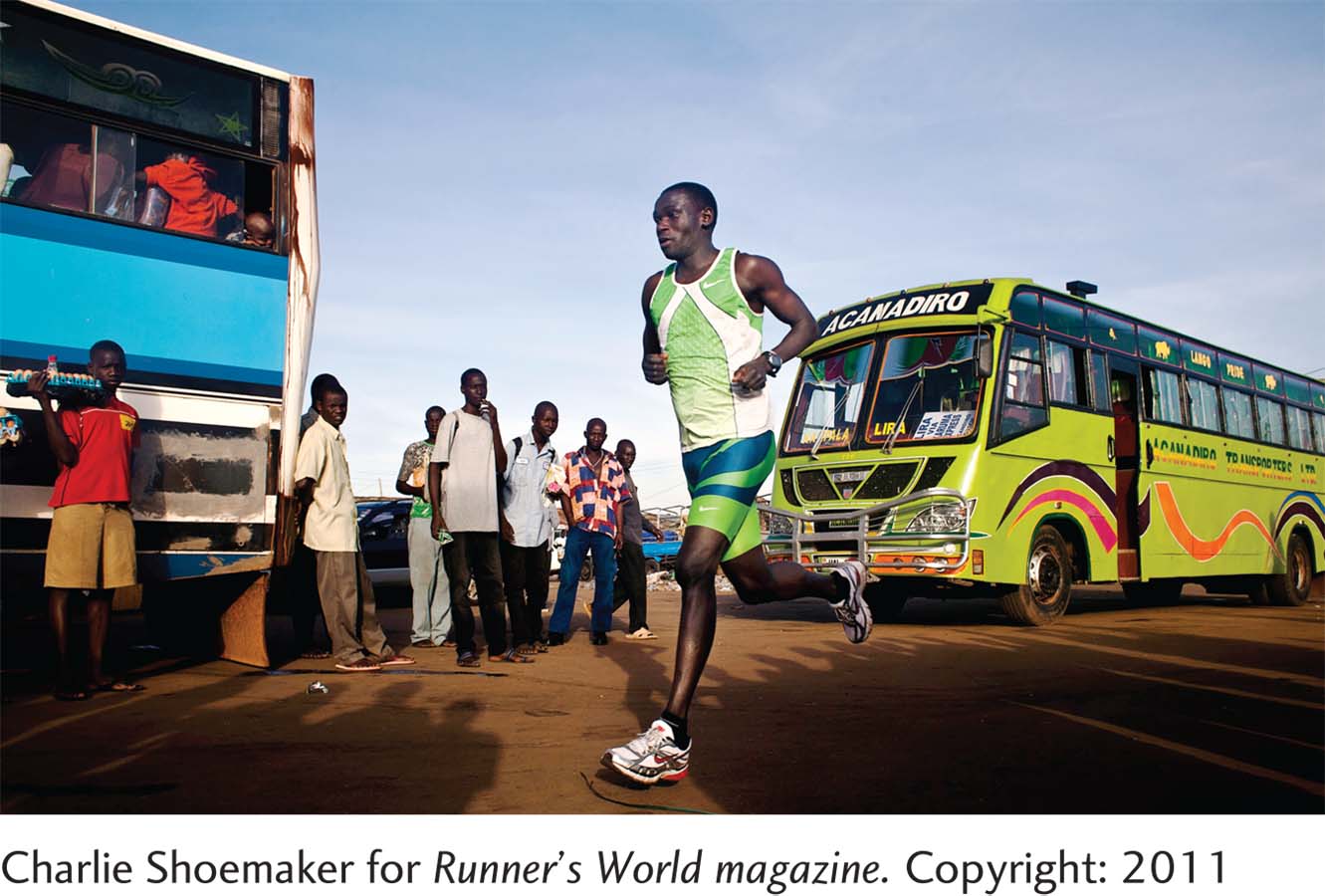

LET’S DO THIS TOGETHER The most important competition of Julius Achon’s career was probably the 1994 World Junior Championships in Portugal. Julius was 17 at the time, and he represented Uganda in the 1,500 meters. It was his first time flying on an airplane, wearing running shoes, and racing on a rubber track. No one expected an unknown boy from Uganda to win, but Julius surprised everyone, including himself. Crossing the finish line strides ahead of the others, he almost looked uncertain as he raised his arms in celebration.

LET’S DO THIS TOGETHER The most important competition of Julius Achon’s career was probably the 1994 World Junior Championships in Portugal. Julius was 17 at the time, and he represented Uganda in the 1,500 meters. It was his first time flying on an airplane, wearing running shoes, and racing on a rubber track. No one expected an unknown boy from Uganda to win, but Julius surprised everyone, including himself. Crossing the finish line strides ahead of the others, he almost looked uncertain as he raised his arms in celebration.

social facilitation The tendency for the presence of others to improve personal performance when the task or event is fairly uncomplicated and a person is adequately prepared.

Julius ran the 1,500 meters (the equivalent of 0.93 miles) in approximately 3 minutes and 40 seconds. Do you suppose he would have run this fast if he had been alone? Research suggests the answer is no (Worringham & Messick, 1983). In some situations, people perform better in the presence of others. This is particularly true when the task at hand is uncomplicated (running) and the individual is well prepared (runners may spend months training for races). Thus, social facilitation can improve personal performance when the activity is fairly straightforward and the person is adequately prepped.

When Two Heads Are Not Better Than One

social loafing The tendency for people to make less than their best effort when individual contributions are too complicated to measure.

Being around other people does not always provide a performance boost, however. Learning or performing difficult tasks may actually be harder in the presence of others (Aiello & Douthitt, 2001), and group members may not put forth their best effort. When individual contributions to the group aren’t easy to ascertain, social loafing may occur (Latané, Williams, & Harkins, 1979). Social loafing is the tendency for people to make less than their best effort when individual contributions are too complicated to measure. Many students will shy away from working in groups because of the negative experiences they have had with other group members’ social loafing.

diffusion of responsibility The sharing of duties and responsibilities among all group members that can lead to feelings of decreased accountability and motivation.

Social loafing often goes hand-

576

Apply This

CUT THE LOAFING

Want some advice on how to reduce social loafing? Even if an instructor doesn’t require it, you should try to get other students in your group to designate and take responsibility for specific tasks, have group members submit their part of the work to the group before the assignment is due, and specify their contributions to the end product (Jones, 2013; Maiden & Perry, 2011). If you do have some “free riders” in your group, don’t automatically assume they are lazy or apathetic. Some group members fail to pull their weight because they feel incompetent (perhaps a result of language difficulties), or they are not “team players” (Barr, Dixon, & Gassenheimer, 2005; Hall & Buzwell, 2012). Communicate with these individuals early in the process, and work with your group to identify a task they can perform with confidence and success.

across the WORLD

Slackers of the West

It turns out that social loafing is more likely to occur in societies where people place a high premium on individuality and autonomy. These individualistic societies include the United States, Western Europe, and other parts of the Western world. In the collectivistic cultures of China and other parts of East Asia, people tend to prioritize community over the individual, and social loafing is less likely to occur. Group members from these more community-

It turns out that social loafing is more likely to occur in societies where people place a high premium on individuality and autonomy. These individualistic societies include the United States, Western Europe, and other parts of the Western world. In the collectivistic cultures of China and other parts of East Asia, people tend to prioritize community over the individual, and social loafing is less likely to occur. Group members from these more community-

IF YOU ARE TRAVELING TO EAST ASIA, SHOULD YOU LEAVE YOUR EGO AT HOME?

Nothing in psychology is ever that simple, however. Social loafing may be less common in collectivist cultures, but it certainly happens (Hong, Wyer, & Fong, 2008). And within every “individualistic” or “collectivistic” society are individuals who do not behave according to these generalities. We should also point out that many group tasks require both individual and shared efforts; in these situations, a combination of individualism and collectivism may lead to more successful outcomes (Wagner, Humphrey, Meyer, & Hollenbeck, 2011).

deindividuation The diminished sense of personal responsibility, inhibition, or adherence to social norms that occurs when group members are not treated as individuals.

DEINDIVIDUATION In the last section, we discussed how obedience played a role in the senseless violence carried out by boy soldiers in Uganda. We suspect that the actions of these children also had something to do with deindividuation. People in groups sometimes feel a diminished sense of personal responsibility, inhibition, or adherence to social norms. This state of deindividuation can occur when group members are not treated as individuals, and thus begin to exhibit a “lack of self-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed a type of descriptive research that involves studying participants in their natural environments. Naturalistic observation requires that the researcher not disturb the participants or their environment. Would Diener’s study be considered naturalistic observation?

Research suggests that children are indeed vulnerable to deindividuation. In a classic study of trick-

577

CONNECTIONS

What else motivated the children who were alone? In Chapter 9, we discussed various sources of motivation, ranging from instincts to the need for power. These sources of motivation might help explain why some children took more than their fair share of candy when they thought no one was watching.

The findings were fascinating. If a parent was present, the children were well behaved (only 8% took more than their allotted one piece of candy). But with no adult present, children acted quite differently. Of the children who came to the door alone and anonymous (the confederate did not ask for names or other identifying information), 21% took more than they should have. By comparison, 80% of the children who were in a group and anonymous took extra candy and/or money. The researchers suggested that the condition of being in a group combined with anonymity created a sense of deindividuation (Diener, Fraser, Beaman, & Kelem, 1976). Are you wondering how much money and candy the kids took? It seems that the children who took more than their fair share of candy grabbed as much as their hands could hold (between 1.6 and 2.3 extra candy bars, on average). As for the money, around 14% of the children stole coins (and ignored the candy), while nearly 21% took both money and more than one piece of candy.

A classic study by Diener and colleagues found that children were most likely to swipe Halloween candy and coins when they were anonymous group members. The condition of being anonymous and part of a group seemed to create a state of deindividuation (Diener et al., 1976).

We have shown how deindividuation occurs in groups of children, but what about adults? Perhaps you have heard about “Bedlam,” a football game between archrival teams from the University of Oklahoma (OU) and Oklahoma State University (OSU). Most years, OU has won, but in 2011, OSU beat OU 44–

risky shift The tendency for groups to recommend uncertain and risky options.

RISKY SHIFT Imagine you have $250,000 to spend for your company. Will you spend more if you’re making decisions alone or working as part of a committee? Researcher James A. F. Stoner (1961, 1968) set out to find the answer to this question, and here’s what he discovered: When group members were asked to make a unanimous decision on how to spend the money, they were more likely to recommend uncertain and risky options than individuals working alone, a phenomenon known as the risky shift.

group polarization The tendency for a group to take a more extreme stance than originally held after deliberations and discussion.

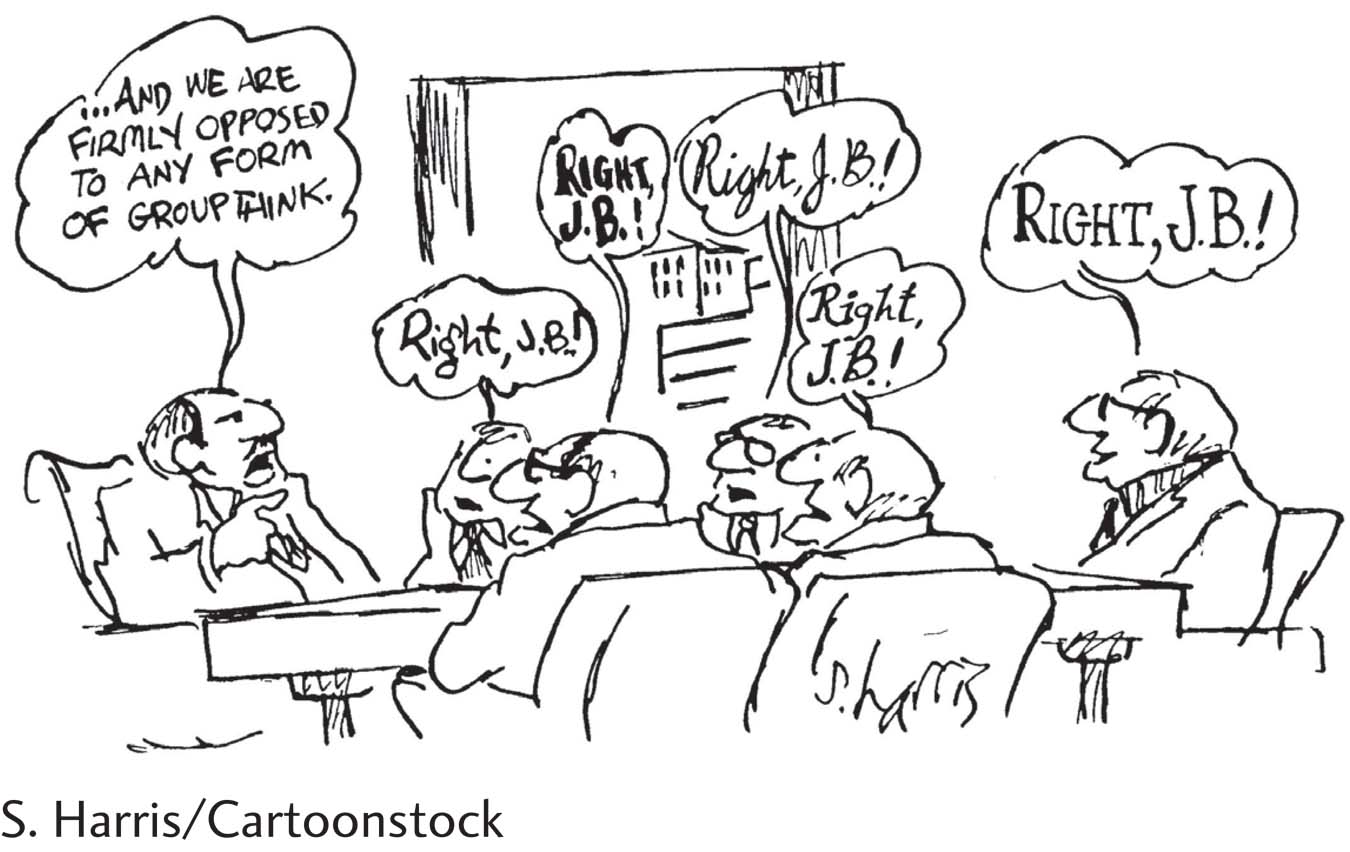

GROUP POLARIZATION AND GROUPTHINK As members of a group work together, their positions tend to become more extreme. For example, if people who strongly support the legalization of marijuana are assembled in a group, their position will become increasingly pro-

578

When group members become increasingly unified, frequently reaching agreement but seldom questioning each other, groupthink has probably taken hold.

groupthink The tendency for group members to maintain cohesiveness and agreement in their decision making, failing to consider possible alternatives and related viewpoints.

As a group becomes increasingly united, another group process known as groupthink can occur. This is the tendency for group members to maintain cohesiveness and agreement in their decision making, failing to consider possible alternatives and related viewpoints (Janis, 1972; Rose, 2011). Groupthink is thought to have played a role in a variety of disasters, including the Challenger space shuttle explosion in 1986, the Mount Everest climbing tragedy in 1996, and the U.S. decision to invade Iraq in 2003 (Badie, 2010; Burnette, Pollack, & Forsyth, 2011).

As you can see, groupthink can have life-

LO 8 Recognize the circumstances that influence the occurrence of the bystander effect.

THE BYSTANDER EFFECT Before meeting Julius, the orphans had been homeless for several months. At night, they kept each other warm coiled beneath the bus, and they shared food when there was enough to go around. Their meals often consisted of scraps that hotels had poured onto side roads for dogs and cats. The orphans leaned on one another, but they didn’t get much assistance from the outside world. Day after day, they encountered hundreds of passersby. Why didn’t anyone try to rescue them? “Everybody was fearing responsibility,” Julius says. In northern Uganda, many people cannot even afford to feed themselves, so they are reluctant to lend a helping hand.

bystander effect The tendency for people to avoid getting involved in an emergency they witness because they assume someone else will help.

But perhaps there was another factor at work, one that psychologists call the bystander effect. When a person is in trouble, bystanders have the tendency to assume (and perhaps wish) that someone else will help—

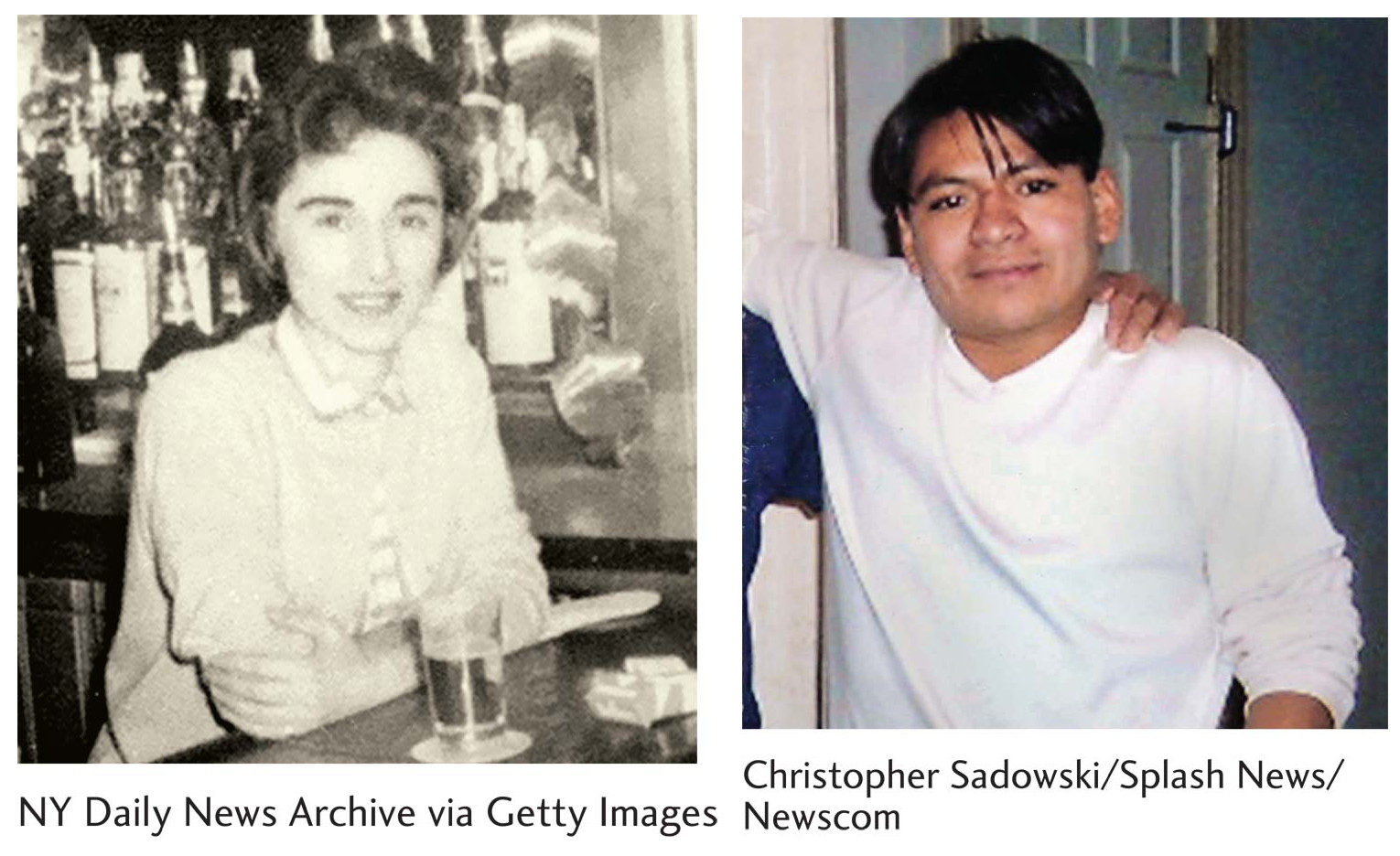

Perhaps the most famous illustration of the bystander effect is the attack on Kitty Genovese. It was March 13, 1964, around 3:15 A.M., when Catherine “Kitty” Genovese arrived home from work in her Queens, New York, neighborhood. As she approached her apartment building, an attacker brutally stabbed her. Kitty screamed for help, but initial reports suggested that no one came to her rescue. The attacker ran away, and Kitty stumbled to her apartment building. But he soon returned, raping and stabbing her to death. The New York Times originally reported that 38 neighbors heard her cries for help, witnessed the attack, and did nothing to assist. But the evidence suggests that the second attack occurred inside her building, where few people could have witnessed it (Manning, Levine, & Collins, 2007).

579

Kitty Genovese (left) and Hugo Tale-

More recently, in April 2010, a homeless man (also in Queens) was left to die after several people walked by him and decided to do nothing. The man, Hugo Tale-

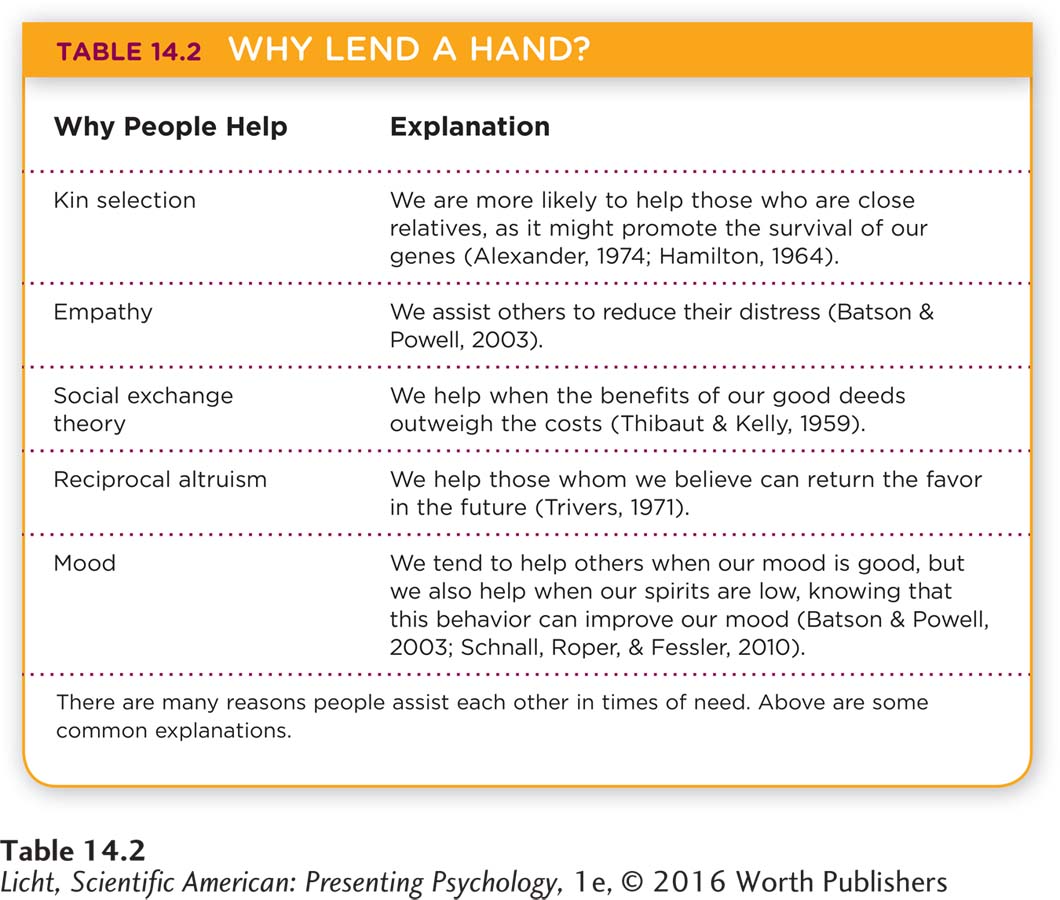

A recent review of the research suggests that things might not be as “bleak” as these events suggest. In extremely dangerous situations, bystanders are actually more likely to help even if there is more than one person watching. More dangerous situations are recognized and interpreted quickly as being such, leading to faster intervention and help (Fischer et al., 2011). If we want to increase the likelihood of bystanders getting involved in stopping violence, the community needs to educate its members about their responsibilities as neighbors and take steps to increase people’s confidence in their ability to help (Banyard & Moynihan, 2011). Take a look at Table 14.2 to learn about factors that increase helping behavior.

Aggression

580

THE ULTIMATE INSULT When Julius attended high school in Uganda’s capital city of Kampala, he never told his classmates that he had been kidnapped by the LRA. “I would not tell them, or anybody, that I was a child soldier,” he says. Had the other students known, they might have called him a rebel—

THE ULTIMATE INSULT When Julius attended high school in Uganda’s capital city of Kampala, he never told his classmates that he had been kidnapped by the LRA. “I would not tell them, or anybody, that I was a child soldier,” he says. Had the other students known, they might have called him a rebel—

LO 9 Demonstrate an understanding of aggression and identify some of its causes.

aggression Intimidating or threatening behavior or attitudes intended to hurt someone.

frustration–

CONNECTIONS

In previous chapters, we noted that identical twins share 100% of their genetic material, whereas fraternal twins share approximately 50%. Here, we see that identical twins are more likely than fraternal twins to share aggressive traits.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapters 7 and 8, we presented the concept of heritability (in relation to intelligence and schizophrenia, for example). Here, we note that around half of the variability in aggressive behavior can be attributed to genes and the other half to environment.

Using racial slurs and hurling threatening insults is a form of aggression. Psychologists define aggression as intimidating or threatening behavior or attitudes intended to hurt someone. Like any phenomenon studied in psychology, aggression results from an interplay of biology and environment. According to the frustration–

The way we express our aggression may be influenced by our gender. Males tend to show more direct aggression (physical displays of aggression such as hitting), while females are more likely to engage in relational aggression—

Gender disparities in aggressive behavior typically appear early in life (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008; Hanish, Sallquist, DiDonato, Fabes, & Martin, 2012), and result from a complex interaction of environmental factors and genetics (Brendgen et al., 2005; Rowe, Maughan, Worthman, Costello, & Angold, 2004). As mentioned, high levels of testosterone have been linked to aggression, and men have more testosterone than women. Social and cultural factors also play a role. Researchers have noted that boys tend to be more aggressive when raised in nonindustrial societies; patriarchal societies, in which women have less power and are considered inferior to men; and polygamous societies, in which men can have more than one wife. Evolutionary psychology would suggest that competition for resources (including females) increases the likelihood of aggression (Wood & Eagly, 2002).

Stereotypes and Discrimination

Julius runs by the Lira bus station where he discovered 11 orphans lying under a bus. Despite all the personal struggles Julius faced—

581

stereotypes Conclusions or inferences we make about people who are different from us based on their group membership, such as race, religion, age, or gender.

Typically, we associate aggression with behavior, but it can also exist in the mind, coloring our attitudes about people and things. This is evidenced by the existence of stereotypes—the conclusions or inferences we make about people who are different from us, based on their group membership (such as race, religion, age, or gender). Stereotypes are often negative (Blonde people are airheads), but they can also be positive (Asians are good at math). Either way, stereotypes can be harmful.

Stereotypes are often associated with a set of perceived characteristics that we think describes members of a group. The stereotypical college instructor is absentminded, absorbed in thought, and unapproachable. The quintessential motorcycle rider is covered in tattoos, and the teenager with the tongue ring is rebelling against her parents. What do all these stereotypes have in common? They are not objective or based on empirical research. In other words, they are like bad theories of personality that characterize people based on a single behavior or trait. These stereotypes typically include a variety of predicted behaviors and traits that are rooted in subjective observations and value judgments.

When Julius was living in Louisiana, a man once approached him and said, “Is it true in Africa people still walk [around] naked?” We can only imagine where this man had gathered his knowledge of Africa (perhaps he had spent a bit too much time flipping through dated issues of National Geographic), but one thing seems certain: He was relying on an inaccurate stereotype of African people. The underlying message was clearly an aggressive one; he judged African people to be primitive and not as advanced as he was.

LO 10 Recognize how group affiliation influences the development of stereotypes.

in-

out-

social identity How we view ourselves within our social group.

GROUPS AND SOCIAL IDENTITY Evolutionary psychologists would suggest that stereotypes allowed human beings to quickly identify the group to which they belonged (Liddle, Shackelford, & Weekes-

ethnocentrism To see the world only from the perspective of one’s own group.

discrimination Showing favoritism or hostility to others because of their affiliation with a group.

DISCRIMINATION Seeing the world from the narrow perspective of our own group may lead to ethnocentrism. This term is often used in reference to cultural groups, yet it can apply to any group (think of football teams, glee clubs, college rivals, or nations). We tend to see our own group as the one that is worthy of emulation, the superior group. This type of group identification can lead to stereotyping, discussed earlier, and discrimination, which involves showing favoritism or hostility to others because of their group affiliation.

scapegoat A target of negative emotions, beliefs, and behaviors; typically, a member of the out-

Those in the out-

prejudice Holding hostile or negative attitudes toward an individual or group.

582

PREJUDICE People who harbor stereotypes and blame scapegoats are more likely to feel prejudice, hostile or negative attitudes toward individuals or groups (Infographic 14.3 on page 584). While racial prejudice has declined in the United States over the last half-

INFOGRAPHIC 14.3

Researchers have concluded that prejudice can be reduced when people are forced to work together toward a common goal. In the early 1970s, Eliot Aronson and colleagues developed the notion of a jigsaw classroom. The teachers created exercises that required all students to complete individual tasks, the results of which would fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The students began to realize the importance of working cooperatively to reach the desired goal. Ultimately, every contribution was an essential piece of the puzzle, and this resulted in all the students feeling valuable (Aronson, 2015).

stereotype threat A “situational threat” in which individuals are aware of others’ negative expectations, which leads to their fear that they will be judged or treated as inferior.

STEREOTYPE THREAT Stereotypes, discrimination, and prejudice are conceptually related to stereotype threat, a “situational threat” in which a person is aware of others’ negative expectations. This leads to a fear of being judged or treated as inferior, and it can actually undermine performance in a specific area associated with the stereotype (Steele, 1997).

African American college students are often the targets of racial stereotypes about poor academic abilities. These threatening stereotypes can lead to lowered performance on tests designed to measure ability, and to a disidentification with the role of a student (in other words, taking on the attitude that I am not a student). Interestingly, a person does not have to believe the stereotype is accurate in order for it to have an impact (Steele, 1997, 2010).

There is a great deal of variation in how people react to stereotype threats (Block, Koch, Liberman, Merriweather, & Roberson, 2011). Some people simply “fend off” the stereotype, by working harder to disprove it. Others feel discouraged and respond by getting angry, either overtly or quietly. Still others seem to ignore the threats. These resilient types appear to “bounce back” and grow from the negative experience. When confronted with a stereotype, they redirect their responses to create an environment that is more inclusive and less conducive to stereotyping.

Unfortunately, stereotypes are pervasive in our society. Just contemplate all the positive and negative stereotypes associated with certain lines of work. Lawyers are greedy, truck drivers are overweight, and (dare we say) psychologists are manipulative. Can you think of any negative stereotypes associated with prison guards? As you read the next feature, think about how stereotypes come to life when people fail to stop and think about their behaviors.

583

CONTROVERSIES

The Stanford “Prison”

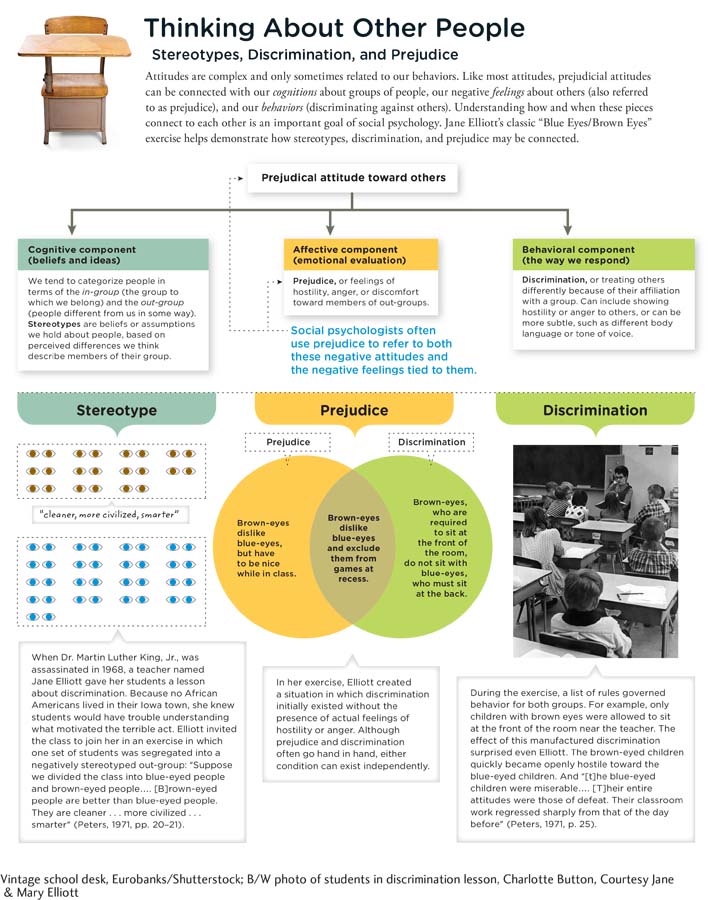

August 1971: Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University launched what would become one of the most controversial experiments in the history of psychology. Zimbardo and his colleagues carefully selected 24 male college students to play the roles of prisoners and guards in a simulated “prison” setup in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology building. (Three of the selected students did not end up participating, so the final number of participants included 10 prisoners and 11 guards.) The young men chosen for the experiment were deemed “normal-

August 1971: Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University launched what would become one of the most controversial experiments in the history of psychology. Zimbardo and his colleagues carefully selected 24 male college students to play the roles of prisoners and guards in a simulated “prison” setup in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology building. (Three of the selected students did not end up participating, so the final number of participants included 10 prisoners and 11 guards.) The young men chosen for the experiment were deemed “normal-

“… LOOKING BACK, I’M IMPRESSED HOW LITTLE I FELT FOR THEM.”

After being “arrested” in their homes by Palo Alto Police officers, the prisoners were searched and booked at a local police station, and then sent to the “prison” at Stanford. The experiment was supposed to last for 2 weeks, but the behavior of the guards and the prisoners was so disturbing the researchers abandoned the study after just 6 days (Haney & Zimbardo, 1998). Some of the guards became abusive, punishing the prisoners, stripping them naked, and confiscating their mattresses. It seemed as if they had lost sight of the prisoners’ humanity, as they ruthlessly wielded their newfound power. As one guard stated, “Looking back, I’m impressed how little I felt for them” (Haney et al., 1973, p. 88). Some prisoners became passive and obedient, accepting the guards’ cruel treatment; others were released early due to “extreme emotional depression, crying, rage, and acute anxiety” (p. 81).

social roles The positions we hold in social groups, and the responsibilities and expectations associated with those roles.

How can we explain this fiasco? The guards and prisoners, it seemed, took their assigned social roles and ran way too far with them. Social roles guide our behavior and represent the positions we hold in social groups, and the responsibilities and expectations associated with those roles.

The prison experiment may have shed light on the power of social roles, but its validity has come under fire. For example, scholars suggest that the participants were merely “acting out their stereotypic images” of guards and prisoners, and behaving in accordance with the researchers’ expectations (Banuazizi & Movahedi, 1975, p. 159). As one guard explained decades later, “I set out with a definite plan in mind, to try to force the action, force something to happen, so that the researchers would have something to work with” (Ratnesar, 2011, July/August, para. 30). Apparently, Zimbardo made his expectations quite clear, instructing the guards to deny the prisoners their “privacy,” “freedom,” and “individuality” (Zimbardo, 2007).

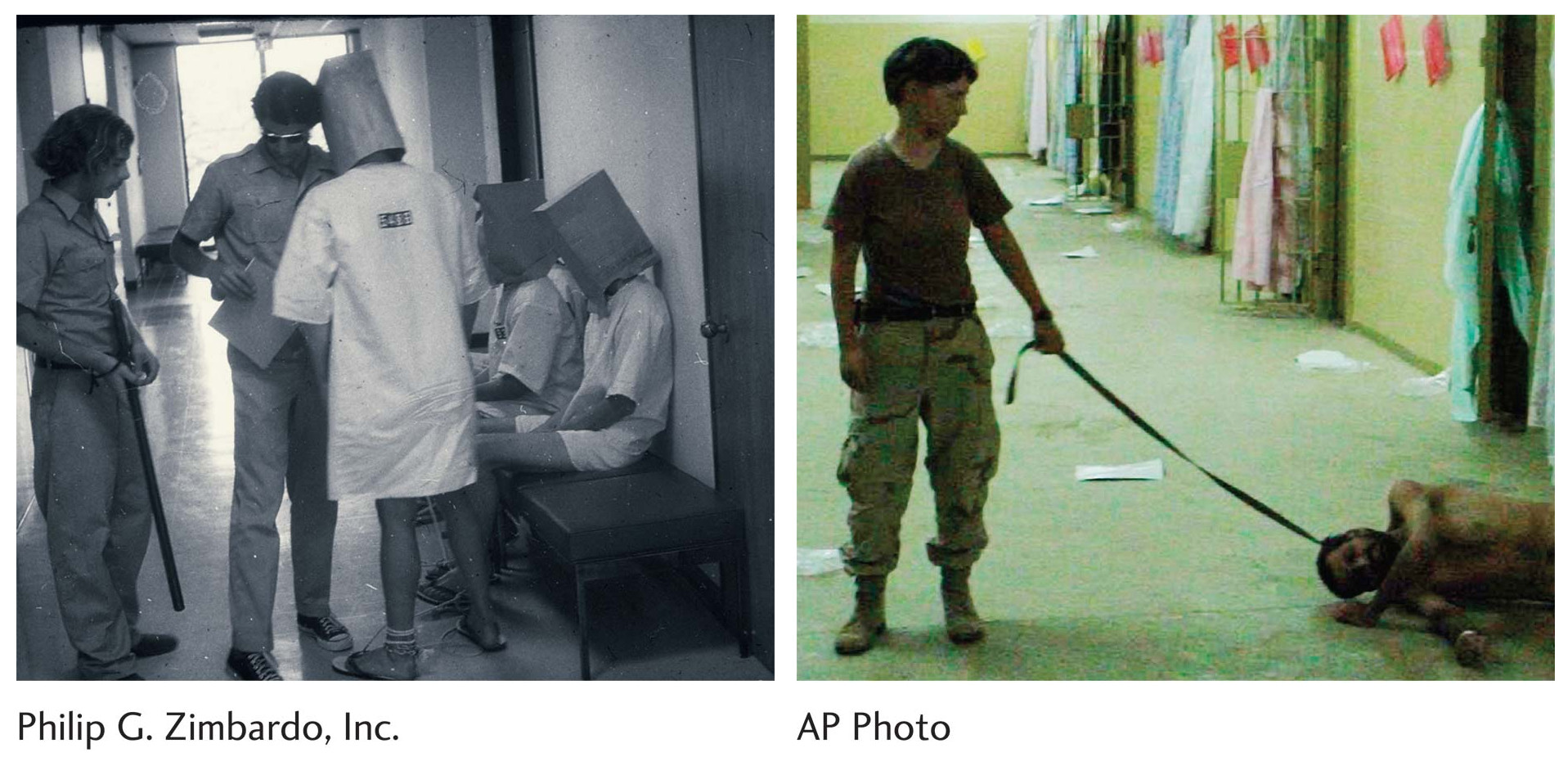

(left) Prisoners in Zimbardo’s 1971 prison experiment are forced to wear bags over their heads. An Abu Ghraib detainee (right) lies on the floor attached to a leash in 2003. The dehumanization and cruel treatment of prisoners in the “Stanford Prison” and the Abu Ghraib facility are disturbingly similar.

Despite its limitations and questionable ethics, the Stanford Prison Experiment continues to be relevant. In 2004, news broke that American soldiers and intelligence officials at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison had beaten, sodomized, and forced detainees to commit degrading sexual acts (Hersh, 2004, May 10). The similarities between Abu Ghraib and the Stanford Prison are noteworthy (Zimbardo, 2007). In both cases, authority figures threatened, abused, and forced inmates to be naked. Those in charge seemed to derive pleasure from violating and humiliating other human beings (Haney et al., 1973; Hersh, 2004, May 10).

584

585

Much of this chapter has focused on the negative aspects of human behavior, such as obedience, stereotyping, and discrimination. While we cannot deny the existence of these phenomena, we believe they are overshadowed by the goodness that lies within every one of us.

show what you know

Question 1

1. ____________ is the tendency for people to not react in an emergency, often thinking that someone else will step in to help.

Group polarization

The risky shift

The bystander effect

Deindividuation

c. The bystander effect

Question 2

2. According to research, which of the following plays a role in aggressive behavior?

low social identity

low levels of the hormone testosterone

low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin

low levels of ethnocentrism

c. low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin

Question 3

3. Name and describe the different displays of aggression exhibited by males and females.

Males tend to show more direct aggression (physical displays of aggression), whereas females are more likely to engage in relational aggression (gossip, exclusion, ignoring), perhaps because females have a higher risk for physical or bodily harm than males do.

Question 4

4. Students often have difficulty identifying how the concepts of stereotypes, discrimination, and prejudice are related. If you were sitting at a table with a sixth-

Answers will vary, but may be based on the following information. Discrimination is showing favoritism or hostility to others because of their affiliation with a group. Prejudice is holding hostile or negative attitudes toward an individual or group. Stereotypes are conclusions or inferences we make about people who are different from us based on their group membership, such as their race, religion, age, or gender. Discrimination, prejudice, and stereotypes involve making assumptions about others we may not know. They often lead to unfair treatment of others.