1.3 Science and Psychology

FRUSTRATED MINERS Extreme circumstances tend to awaken the darker elements of human nature, and the Chilean mining ordeal was no exception. During those first 17 days underground, the men split into three factions, each with its own designated leader and sleeping territory. They squabbled over pieces of cardboard that they used as mattresses, and a few arguments reportedly escalated into fistfights (CBS News/Associated Press, 2010, October 16; Franklin, 2011). But the same life-

FRUSTRATED MINERS Extreme circumstances tend to awaken the darker elements of human nature, and the Chilean mining ordeal was no exception. During those first 17 days underground, the men split into three factions, each with its own designated leader and sleeping territory. They squabbled over pieces of cardboard that they used as mattresses, and a few arguments reportedly escalated into fistfights (CBS News/Associated Press, 2010, October 16; Franklin, 2011). But the same life-

The men were able to move beyond their personal disputes and see the big picture. They realized that banding together was the only sensible way to endure. Like players on a team, they began to assume special roles and responsibilities. The “pastor” José Henríquez led the group in regular prayers; the “electrician” Edison Peña cobbled together a bootleg lighting system; and the “doctor” Yonni Barrios drew from the knowledge of medicine he learned while caring for his sick mother. The miners selected two very different yet complementary leaders: the foreman Luis Urzúa and a second unofficial leader named Mario Sepúlveda. Formerly known as “El Loco” or the “Crazy One,” Sepúlveda once pole-

The miners looked to Mario Sepúlveda for support and guidance during their 10-

To break the monotony of their subterranean existence, the miners coordinated their daily activities, starting their morning with a prayer, holding a midday “townhall” meeting where they voted democratically on all major decisions, and praying again in the afternoon. When it was time for their daily meal, they gathered like a family, politely waiting to eat until all 33 members had been served (Franklin, 2011).

The men experienced their share of psychological meltdowns during those first 17 days, but they found comfort in the bonds of brotherhood. “We were like a family,” said Samuel Ávalos. “When someone falls, you pick them up” (Franklin, 2011, p. 103). And like very close family members, they could almost feel each other’s pain. “I was more worried about my companions,” said Ávalos, referring to the younger men who had just started families. “They had little babies, pregnant wives. That broke me. . . . To see my compañeros cry and cry” (p. 109).

The roles these men assumed, the ways in which they cooperated, and the emotional support they offered to each other are just the types of social dynamics that scientists would be interested in studying (Chapter 14). Equally interesting was the manner in which people throughout the world responded when they learned that rescuers had made contact with the miners.

THINK again

What’s in a Number?

News of the trapped miners was headlined, broadcast, and tweeted across the globe. People found it difficult to believe that all 33 men had survived. Some said it was testament to the endurance of the human spirit. Others called it a miracle of God. Still others pointed to the mystical nature of numerology, which attempts to provide explanations for a variety of events and observations. The number 33, which numerologists consider a “master number” (Decoz, 2011, April 18), was thought to play an important role. Here is some of the “evidence” presented to support this claim (Agence France Presse, 2010, October 14; freedomflores, 2010, October 18; The Vigilant Citizen, 2010, October 14):

News of the trapped miners was headlined, broadcast, and tweeted across the globe. People found it difficult to believe that all 33 men had survived. Some said it was testament to the endurance of the human spirit. Others called it a miracle of God. Still others pointed to the mystical nature of numerology, which attempts to provide explanations for a variety of events and observations. The number 33, which numerologists consider a “master number” (Decoz, 2011, April 18), was thought to play an important role. Here is some of the “evidence” presented to support this claim (Agence France Presse, 2010, October 14; freedomflores, 2010, October 18; The Vigilant Citizen, 2010, October 14):

NUMEROLOGY TO THE RESCUE?

There were 33 miners.

They sent up a note saying, “Estamos bien en el refugio los 33.” This statement contains 33 characters and spaces.

The eventual rescue date was 10/13/10; the sum of these digits equals 33.

Drilling the rescue tunnel took 33 days, and the width of the rescue tunnel was said to be 66 centimeters, which is 33 times two.

Are you detecting a pattern? The fact is, anyone can draw a connection or find a pattern if they try hard enough, and these patterns do not necessarily represent a unifying theory or provide a scientific explanation. They are just coincidences.

While the beliefs surrounding numerology may have provided a meaningful way for some people to interpret the miners’ experiences, such beliefs have no scientific validity. In the following section, we’ll examine “pseudosciences” like numerology and explain how we use critical thinking to evaluate how they compare to scientific research and thought.

LO 5 Evaluate pseudopsychology and its relationship to critical thinking.

pseudopsychology An approach to explaining and predicting behavior and events that appears to be psychology, but has no empirical or objective evidence to support it.

As intriguing as this apparent 33 theme may be, it has no scientific meaning. Numerology is a prime example of pseudopsychology, an approach to explaining and predicting behavior and events that appears to be psychology but is not supported by objective evidence. Another familiar pseudopsychology is astrology, which uses a chart of the heavens called a horoscope to predict everything from the weather to romantic relationships. Surprisingly, many people have difficulty distinguishing between pseudosciences, like astrology, and true sciences, even after earning a college degree (Impey, Buxner, & Antonellis, 2012; Schmaltz & Lilienfeld, 2014).

Why does astrology often seem to be accurate in its descriptions and predictions? Consider this excerpt from a monthly Gemini horoscope: “You could meet a lot of fascinating people and make many new friends as autumn begins. You could also take up a creative new interest or hobby” (Horoscope.com, 2014). When you think about it, this statement could apply to just about any human being on the planet. We all are capable of starting new activities and meeting “fascinating people” (isn’t every person “fascinating” in her own way?). How could you possibly prove such a statement wrong? You couldn’t. That’s why astrology is not science. A telltale feature of a pseudopsychology, like any pseudoscience, is its tendency to make assertions so broad and vague that they cannot be refuted (Stanovich, 2013).

Critical Thinking

critical thinking The process of weighing various pieces of evidence, synthesizing them, and evaluating and determining the contributions of each.

Why can’t we use pseudopsychology to help predict and explain behaviors? Because there is no solid evidence for its effectiveness, no scientific support for its findings. Critical thinking is absent from the “pseudotheories” used to explain the pseudosciences (Rasmussen, 2007; Stemwedel, 2011). What is critical thinking and when should we use it? Critical thinking is the process of weighing various pieces of evidence, synthesizing them (putting them together), and determining how each contributes to the bigger picture. Critical thinking requires one to consider the source of information and the quality of evidence before making a decision on its validity. The process involves thinking beyond definitions, focusing on underlying concepts and applications, and being open-

Let’s put our critical thinking skills to work by examining the numerological “evidence” pertaining to Los 33. First, can we trust the data? One source suggests the rescue hole was 66 centimeters, but another says it was 68 centimeters. Some miners were rescued on 10/13/10, but others emerged on 10/14/10 (the rescue took place over the course of 2 days). Hmm, some of the 33s appear to be fading into thin air. Lesson learned: We should use critical thinking to evaluate the evidence for a claim.

But critical thinking goes far beyond verifying the facts (Yanchar, Slife, & Warne, 2008). Even if every piece of numerological evidence was spot-

Critical thinking is an invaluable skill, whether you are a trapped miner struggling to survive, a psychologist planning an experiment, or a student trying to earn a good grade in psychology class. For example, has anyone ever told you that choosing “C” on a multiple-

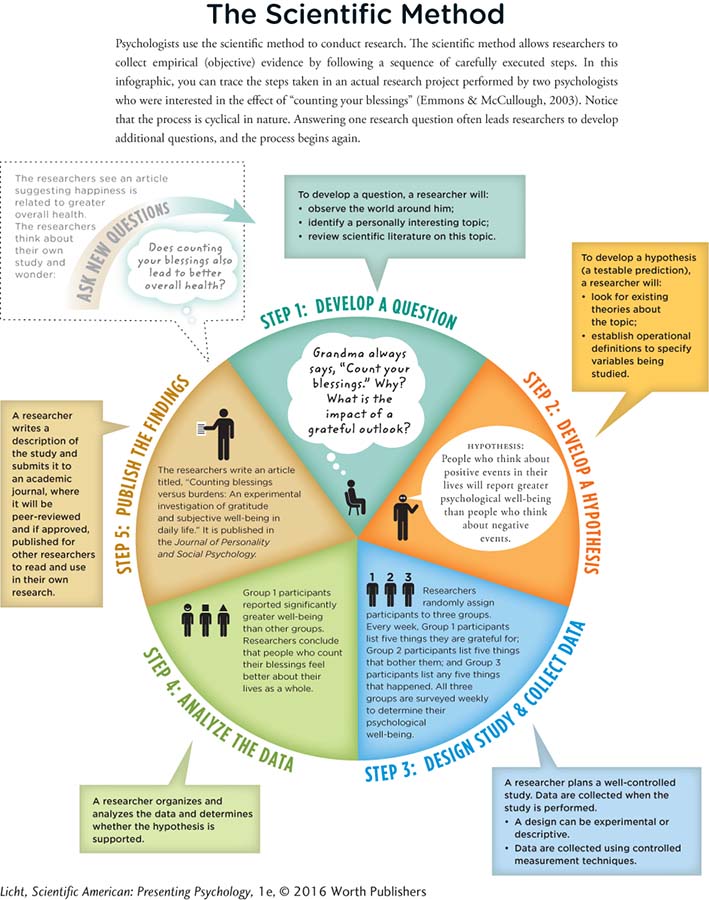

The Scientific Method

LO 6 Describe how psychologists use the scientific method.

scientific method The process scientists use to conduct research, which includes a continuing cycle of exploration, critical thinking, and systematic observation.

experiment A controlled procedure that involves careful examination through the use of scientific observation and/or manipulation of variables (measurable characteristics).

Critical thinking is an important component of the scientific method, the process scientists use to conduct research. The goal of the scientific method is to provide empirical evidence, or data from systematic observations or experiments. An experiment is a controlled procedure involving scientific observations and/or manipulations by the researcher to influence participants’ thinking, emotions, or behaviors. In the scientific method, an observation must be objective, or outside the influence of personal opinion and preconceived notions. Humans are prone to errors in thinking (Chapter 7), but the scientific method helps to minimize their impact.

Suppose a researcher had tried to determine whether any of the Chilean miners was running a fever. He might have asked the crew’s “doctor,” Yonni Barrios, to place his hand on each man’s forehead, but Barrios’ measurement of “fever” could have been different from the researcher’s. A more objective approach would have been to send down a thermometer to the mine. Observations that are truly objective do not differ from one person to the next based on beliefs or opinions. A thermometer will read the same whether it’s being used by Yonni Barrios or a new parent. Now let’s take a look at the 5 basic steps of the scientific method.

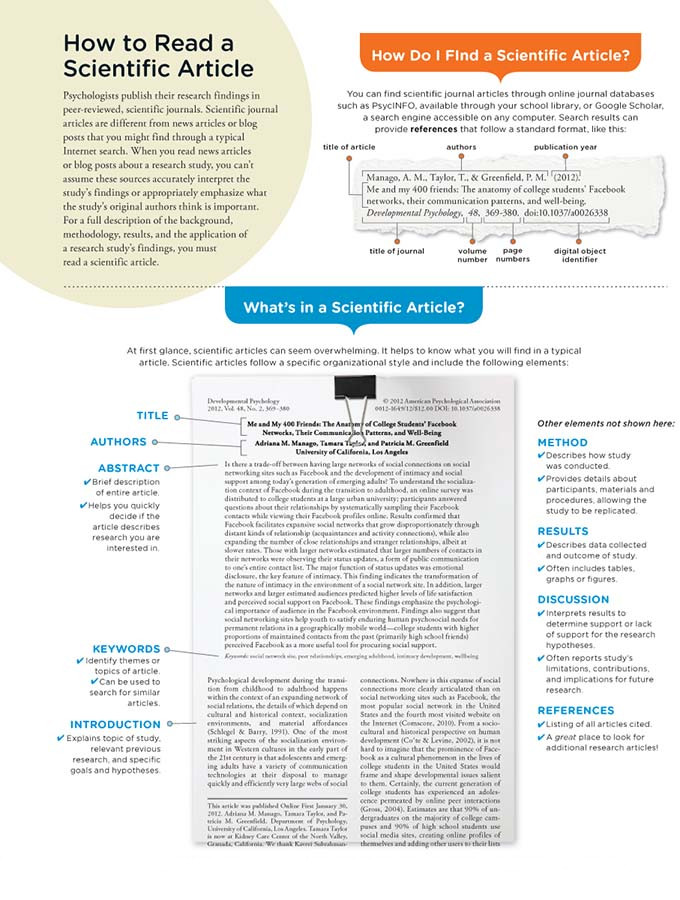

STEP 1: DEVELOP A QUESTION The scientific method typically begins when a researcher observes something interesting in the environment and comes up with a research question. A great way to start this process is to read books and articles written by scientists. (See Infographic 1.2 to get a sense of how best to find and read an article; learning these skills will help you in many classes you take, including psychology.) Imagine that a psychologist has decided to study the psychological health of the trapped miners. While reviewing the literature on this topic, he comes across several studies suggesting that disaster survivors face an elevated risk for depression (Bonanno, Brewin, Kaniasty, & La Greca, 2010). This makes the psychologist wonder: Will Los 33 experience rates of depression similar to those of other disaster victims, or do their unique circumstances place them in a category all their own?

Apply This

INFOGRAPHIC 1.2

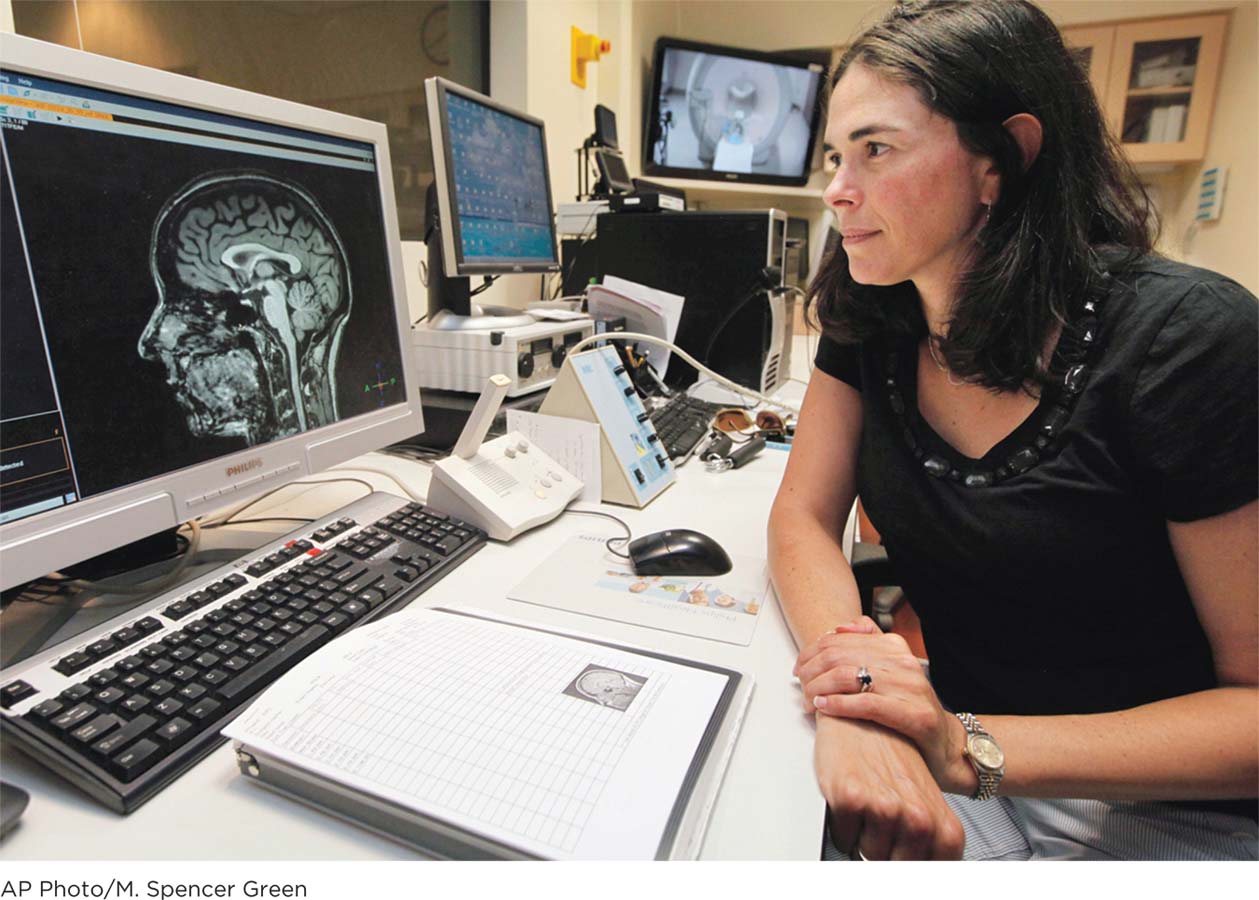

Sian Beilock, a psychologist from the University of Chicago, examines an fMRI scan. Using brain imaging and other types of objective data such as behavioral observations and cortisol levels in the saliva, Dr. Beilock studies the psychological mechanisms that underlie “choking under pressure,” or faltering under stress (University of Chicago, 2013).

hypothesis (hī-̍pä-thə-səs) A statement that can be used to test a prediction.

STEP 2: DEVELOP A HYPOTHESIS Once a research question has been developed, the next step in the scientific method is to formulate a hypothesis (hī-̍pä-thə-səs), a statement that can be used to test a prediction. The psychologist might come up with a hypothesis that reads something like this: “If we treat half of the survivors from the San José mining disaster with therapy and put the other half on a waiting list for therapy, those on the waiting list will be more likely to receive a diagnosis of depression within 5 years of rescue.” The data collected by the experimenter will either support or refute the hypothesis. Hypotheses are difficult to generate for studies on new and unexplored topics; in these situations, a general prediction may take the place of a formal hypothesis.

theory Synthesizes observations in order to explain phenomena and guide predictions to be tested through research.

While developing research questions and hypotheses, researchers should always be on the lookout for information that could offer explanations for the phenomenon they are studying. For a study on depression, this might entail reviewing theories about the causes of depression. Theories synthesize observations in order to explain phenomena, and they can be used to make predictions that can then be tested through research. Many people believe scientific theories are nothing more than unverified guesses or hunches, but they are mistaken (Stanovich, 2013). A theory is a well-

operational definition The precise manner in which a variable of interest is defined and measured.

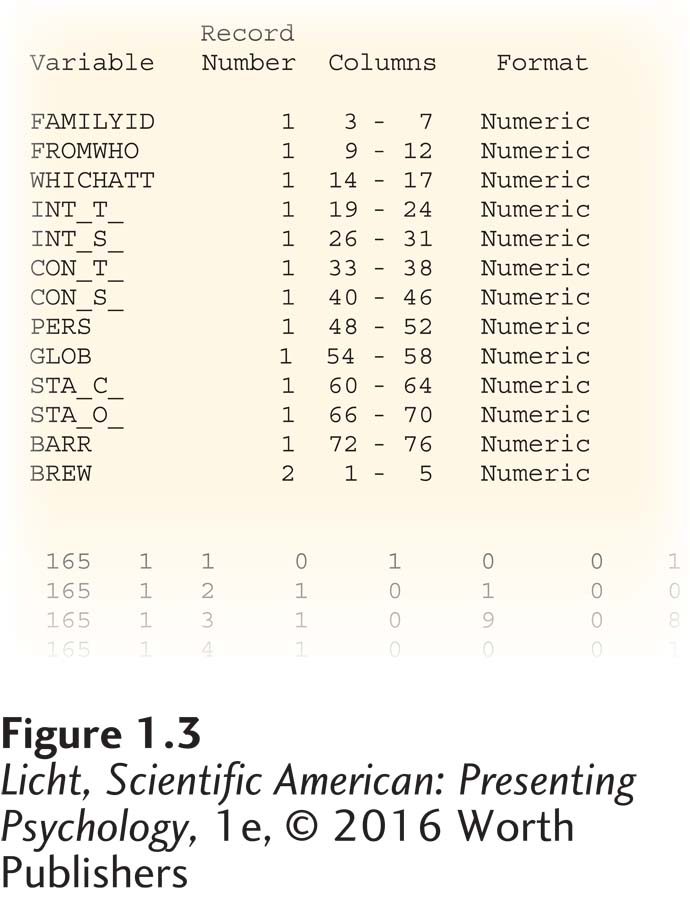

The information in this figure comes from a data file. Until the researcher analyzes the data, these numbers will have little meaning.

STEP 3: DESIGN STUDY AND COLLECT DATA Once a hypothesis has been developed, the researcher designs an experiment to test it. Operational definitions specify the precise manner in which the characteristics of interest are defined and measured. For example, the psychologist might have used a depression scale to measure the mood of the miners, and then defined depression based on a cutoff point (anyone with a score greater than 40, for example). According to the scientific method, a good operational definition helps others understand how to perform an observation or take a measurement.

The researcher then collects the data to test the hypothesis. Gathering data must be done in a very controlled fashion to ensure there are no errors, which could arise from recording problems or from unknown environmental factors. We will address the basics of data collection later in the chapter.

STEP 4: ANALYZE THE DATA The researcher now has data that need to be analyzed, or organized in a meaningful way. As you can see from Figure 1.3, rows and columns of numbers are just that, numbers. In order to make sense of the “raw” data, one must use statistical methods. Descriptive statistics are used to organize and present data, often through tables, graphs, and charts. Inferential statistics, on the other hand, go beyond simply describing the data set, allowing researchers to make inferences and determine the probability of events occurring in the future (for a more in-

Once the data have been analyzed, the researcher must ask several questions: Did the results support the hypothesis? Were the predictions met? He evaluates his hypothesis, rethinks his theories, and possibly designs a new study. This procedure is an important part of the scientific method because it enables us to think critically about our findings. In the hypothetical depression study of Los 33, what if the researcher found no differences between the therapy and nontherapy groups? Was the type of therapy used ineffective? Were the tools for measuring depression problematic? If these ideas are worth pursuing, the researcher could develop a new hypothesis and embark on a study to test it. Look at Infographic 1.3 and notice the cyclical nature of the scientific method.

INFOGRAPHIC 1.3

Actors Jenny McCarthy and Jim Carrey lead a rally calling for changes in childhood vaccines. Studies suggest that routine vaccinations are safe, but some parents believe they trigger autism, a misconception stemming from a widely publicized but problematic study published in a peer-

STEP 5: PUBLISH THE FINDINGS Once the data have been analyzed and the hypothesis tested, it’s time to share findings with other researchers who might be able to build on the work. This typically involves writing a scientific article and submitting it to a scholarly, peer-

The peer-

In the late 1990s, researchers published a study suggesting that vaccination against infectious diseases caused autism (Wakefield et al., 1998). The findings sparked panic among parents, including the actress Jenny McCarthy, who led a march in Washington, DC, calling for changes in vaccination policies. The study turned out to be fraudulent and the reported findings were deceptive, but it took 12 years for journal editors to retract the article (Editors of The Lancet, 2010). One reason for this long delay was that researchers had to investigate all the accusations of wrongdoing and data fabrication (Godlee, Smith, & Marcovitch, 2011). The investigation included interviews with the parents of the children discussed in the study, which ultimately led to the finding that the information in the published account was inaccurate (Deer, 2011).

Since the publication of that flawed study, several high-

replicate To repeat an experiment, generally with a new sample and/or other changes to the procedures, the goal of which is to provide further support for the findings of the first study.

Publishing an article is a crucial step in the scientific process because it allows other researchers to replicate an experiment, which might mean repeating it with other participants or altering some of the procedures. This repetition is necessary to ensure that the initial findings were not just a fluke or the result of a poorly designed experiment.

In the case of Wakefield’s fraudulent autism study, other researchers tried to replicate the study for over 10 years, but could never establish a relationship between autism and vaccines (Godlee et al., 2011). This fact alone made the Wakefield findings suspect. The more a study is replicated and produces similar findings, the more confidence we can have in those findings.

ASK NEW QUESTIONS Most studies generate more questions than they answer, and here lies the beauty of the scientific process. The results of one scientific study raise a host of new questions, and those questions lead to new hypotheses, new studies, and yet another collection of questions. This continuing cycle of exploration uses critical thinking at every step in the process.

Research Basics

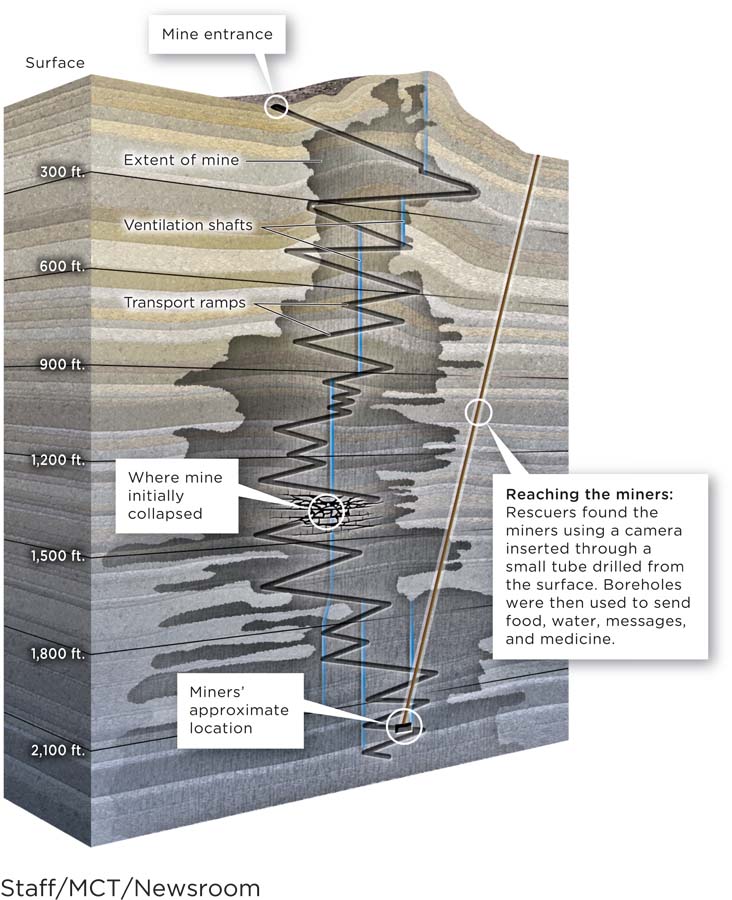

THE BIG WAIT The miners’ first 17 days underground were intense and grueling, but now they faced the ultimate test of psychological endurance: waiting up to 4 months for rescuers to bore an escape tunnel. Could they go the distance? The circumstances of their cave-

THE BIG WAIT The miners’ first 17 days underground were intense and grueling, but now they faced the ultimate test of psychological endurance: waiting up to 4 months for rescuers to bore an escape tunnel. Could they go the distance? The circumstances of their cave-

The wife of trapped miner Mario Gomez writes him a letter.

The miners communicated with the outside world through 6-

Recognizing the extraordinary psychological battle the miners faced, a team of psychologists was assembled to oversee their mental health (Franklin, 2011). Physicians and the lead psychologist Alberto Iturra began holding daily conference calls with the miners using a makeshift telephone line running through one of the boreholes. (A total of three narrow bore holes were drilled in order to facilitate communication and the delivery of food, medicine, and other necessities [Associated Press, 2010, August 30].) The relationship between Iturra and the miners was congenial at first, but feelings turned sour when Iturra began to meddle with the men’s communications. He recommended, for example, that the miners be allotted only 1 minute for their first conversation with family members. According to one miner, Iturra actually got on the line and said “cut” when a miner’s time was up. The psychologists also began to read personal letters sent from the miners to their families, and vice versa, censoring every piece of mail flowing in and out of the mine. Apparently, they were concerned that certain types of news (such as family and financial troubles) might be too much for the already stressed miners to bear. But this censorship incited something of a rebellion among the group (Franklin, 2011).

Mental health experts across the globe weighed in on the matter. Psychiatrist Nick Kanas of the University of California deemed it unwise to censor communications between the miners and the outside world. “I would not screen anything. . . . Otherwise you are setting up a basis for mistrust,” Kanas told journalist Jonathan Franklin (Franklin, 2011, p. 152). “Any attempt to be not entirely forthcoming [by rescuers] could be seen as a lack of trust,” said psychologist Lawrence Palinkas of the University of Southern California in an interview with Discovery News (O’Hanlon, 2010, August 31).

No psychologist had ever studied human beings in a scenario quite like this. There were no “lessons learned” from past experience, no guidelines to follow, and certainly no research on the subject. The best Iturra and his colleagues could do was draw on studies of people in similar situations—

Imagine you had the opportunity to conduct research on Los 33. Soon we will discuss two major categories of research design you could use—

variables Measurable characteristics that can vary over time or across people.

On Chile’s Independence Day, the miners received a special delivery from on high: empanadas, or delicious pastries filled with meat, olives, raisins, and egg (Penhaul, 2010, September 18). How might such comfort food have affected the men’s moods?

VARIABLES Virtually every psychology study includes variables, or measurable characteristics that vary, or change, over time or across people. In chemistry, a variable might be temperature, mass, or volume. In psychological experiments, researchers study a variety of characteristics pertaining to humans and other organisms. Examples of variables include personality characteristics (shyness or friendliness), cognitive characteristics (memory), number of siblings in a family, gender, socioeconomic status, and so forth. A psychologist studying the miners might be interested in variables related to mood, leadership qualities, competitiveness, or educational background. In many experiments, the goal is to see how changing one variable affects another. In the Chilean miner example, a researcher might be interested in knowing how the delivery of empanadas, delicious stuffed pastries, affected the miners’ moods. Once the variables for a study are chosen, researchers must create operational definitions with precise descriptions and manners of measurement.

LO 7 Summarize the importance of a random sample.

population All members of an identified group about which a researcher is interested.

sample A subset of a population chosen for inclusion in an experiment.

POPULATION AND SAMPLE How do researchers decide who should participate in their studies? It depends on the population, or overall group, the researcher wants to examine. If the population is large (all college students in the United States, for example), then the researcher selects a subset of that population called a sample.

random sample A subset of the population chosen through a procedure that ensures all members of the population have an equally likely chance of being selected to participate in the study.

representative sample A subgroup of a population selected so that its members have characteristics similar to those of the population of interest.

There are many methods for choosing a sample. One way is to pick a random sample, that is, theoretically any member of the population has an equally likely chance of being selected to participate in the study. Think about the problems that may occur if the sample is not random. Suppose a researcher is trying to assess attitudes about banning supersized sugary sodas in the United States, but the only place she recruits participants is New York City, where such a ban was implemented for some time. How might this bias her findings? New York City residents do not constitute a representative sample, or group of people with characteristics similar to those of the population of interest.

If a researcher aimed to understand American attitudes about supersized soda bans, she would be foolish to limit her study to residents of New York City. Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of the Big Apple, called for a ban on the sale of supersized sugary drinks in 2012. The controversial law probably affected attitudes about the issue, even though it was subsequently struck down. Thus, the people of New York City do not constitute a representative sample.

It is important for the researcher to choose a representative sample, because this allows her to generalize her findings, meaning to apply information from a sample to the population at large. Let’s say that 44% of the respondents in her study believe supersized sugary sodas should be banned. If her sample was similar enough to the overall U.S. population, then she may be able to infer that this finding from the sample is representative: “Approximately 44% of people in the United States believe that supersized sugary sodas should be banned.”

informed consent Acknowledgment from study participants that they understand what their participation will entail.

INFORMED CONSENT The researcher has chosen the population of interest, and she has identified her sample, but she needs to make certain that these people are comfortable participating in her research. Before she can begin to collect data, she must obtain informed consent, or acknowledgment from the participants that they understand what their participation will entail, including any possible harm that could result. Informed consent is a participant’s way of saying, “I understand my role in this study, and I am okay with it,” and it’s the researcher’s way of ensuring that participants know what they are getting into.

debriefing Sharing information with participants after their involvement in a study has ended, including the purpose of the study and of deception used in it.

Institutional Review Board (IRB) A committee that reviews research proposals to protect the rights and welfare of all participants.

Synonyms

Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewing committee, Animal Welfare Committee, Independent Ethics Committee, Ethical Review Board

DEBRIEFING Following the study, there is another step of disclosure known as debriefing. In a debriefing session, researchers provide participants with useful information related to the study. In some cases, participants are informed of the deception or manipulation they were exposed to in the study, information that couldn’t be shared with them beforehand. You will soon learn why a small dose of duplicity sometimes comes in handy for scientific research. And rest assured, all experiments on humans and animals must be approved by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure the highest degree of ethical standards.

The topics we have touched on thus far—

THE MINERS GET THEIR WAY > After nearly a month of working with lead psychologist Alberto Iturra, the miners demanded that he be dismissed. They were tired of the psychologists reading and editing their letters, searching care packages, and punishing them for refusing to go along with Iturra’s agenda. The miners issued an ultimatum: Either Iturra goes, or we stop eating. Their strategy worked, at least temporarily; Iturra agreed to take a 1-

THE MINERS GET THEIR WAY > After nearly a month of working with lead psychologist Alberto Iturra, the miners demanded that he be dismissed. They were tired of the psychologists reading and editing their letters, searching care packages, and punishing them for refusing to go along with Iturra’s agenda. The miners issued an ultimatum: Either Iturra goes, or we stop eating. Their strategy worked, at least temporarily; Iturra agreed to take a 1-

positive psychology An approach that focuses on the positive aspects of human beings, seeking to understand their strengths and uncover the roots of happiness, creativity, humor, and so on.

Ibañez was trained in positive psychology, a relatively new approach that studies the positive aspects of human nature—

Ibañez’s more laid-

show what you know

Question 1

1. An instructor in the psychology department assigns a project requiring students to read several journal articles on a controversial topic. They are then required to weigh various pieces of evidence from the articles, synthesize the information, and determine how the various findings contribute to understanding the topic. This process is known as:

pseudotheory.

critical thinking.

hindsight bias.

applied research.

b. critical thinking

Question 2

2. How would you explain to someone that astrology is a pseudopsychology?

Astrology is a great example of a pseudopsychology, an approach to explaining and predicting behavior and events that appears to be psychology but lacks scientific support. If you search the scientific literature for empirical, objective studies supporting astrological claims, you will have a very difficult time finding any. Another sign astrology is a pseudoscience is that its predictions are often too broad to refute. Let’s say an astrologer predicts that a friend or close family member will soon need your kind words and support. Such a prediction would likely apply to the great majority of people, as family members and friends often look to each other for strength. Such a prediction would always seem to come true, because the probability of its occurrence is almost 100%.

Question 3

3. A researcher identifies affection between partners by counting the number of times they gaze into each other’s eyes while in the laboratory waiting room. The cutoff for those who would be considered very affectionate partners is gazing more than 10 times in 1 hour. The researcher has created a(n) _____________________ of affection.

theory

hypothesis

replication

operational definition

d. operational definition

Question 4

4. A researcher is interested in studying college students’ attitudes about banning supersized sodas. She randomly selects a group of students from across the nation, trying to pick a _____________________ that will closely reflect the characteristics of college students in the United States.

variable

debriefing

representative sample

representative population

c. representative sample