3.5 Perception

We have learned how the sensory systems absorb information and transform it into the electrical and chemical language of neurons. Now let’s look more closely at the next step: perception, which draws from experience to organize and interpret sensory information, turning sensory data into something meaningful. Perhaps the most important lesson you will learn in this section is that perception is far from foolproof. We don’t see, hear, smell, taste, or feel the world exactly as it is, but as our brains judge it to be.

Illusions: The Mind’s Imperfect Eye

When your friend texts you a smiley face, data-

What you see is not always what you get. Consider this experiment: Researchers asked a group of undergraduates studying oenology (the study of wine) to sample two beverages. One was a white wine, and the other was the exact same white wine—

illusion A perception incongruent with sensory data.

A great way to detect distortions in perceptual processes is to study illusions. An illusion is a perception that is incongruent with real sensory data, conveying an inaccurate representation of reality. Looking at perception when it is working “incorrectly” allows us to examine knowledge-

Look at the Müller-

The golf club and golf ball seem to be moving because their images appear in rapid succession. Stroboscopic motion is an example of a visual illusion.

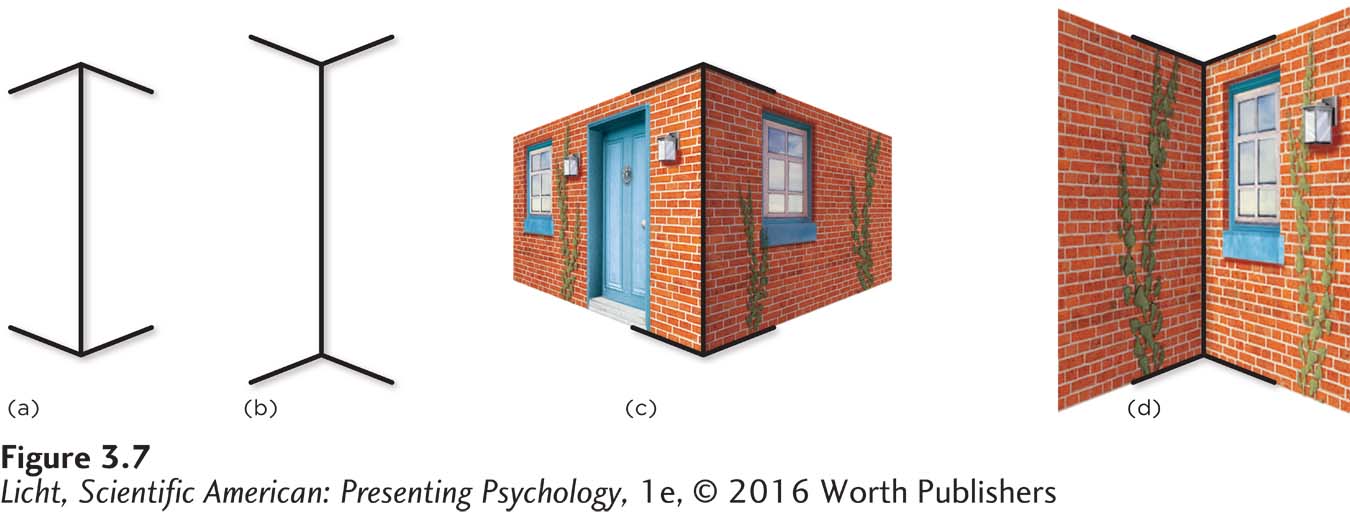

Which line looks longer? They are actually the same length. Visual depth cues cause you to perceive that (b) and (d) are longer because they appear farther away.

Another visual illusion is stroboscopic motion, the appearance of motion produced when a sequence of still images are shown in rapid succession. (Think of drawing stick figures on the edges of book pages and then flipping the pages to see your figure “move.”) The brain interprets this as movement. Even infants appear to perceive this kind of motion (Valenza, Leo, Gava, & Simion, 2006). Although illusions provide clues about how perception works, they cannot explain everything. Let’s take a look at principles of perceptual organization, which provide universal guidelines on how we perceive our surroundings.

Perceptual Organization

LO 13 Identify the principles of perceptual organization.

gestalt (gə-ˈstält) The natural tendency for the brain to organize stimuli into a whole, rather than perceiving the parts and pieces.

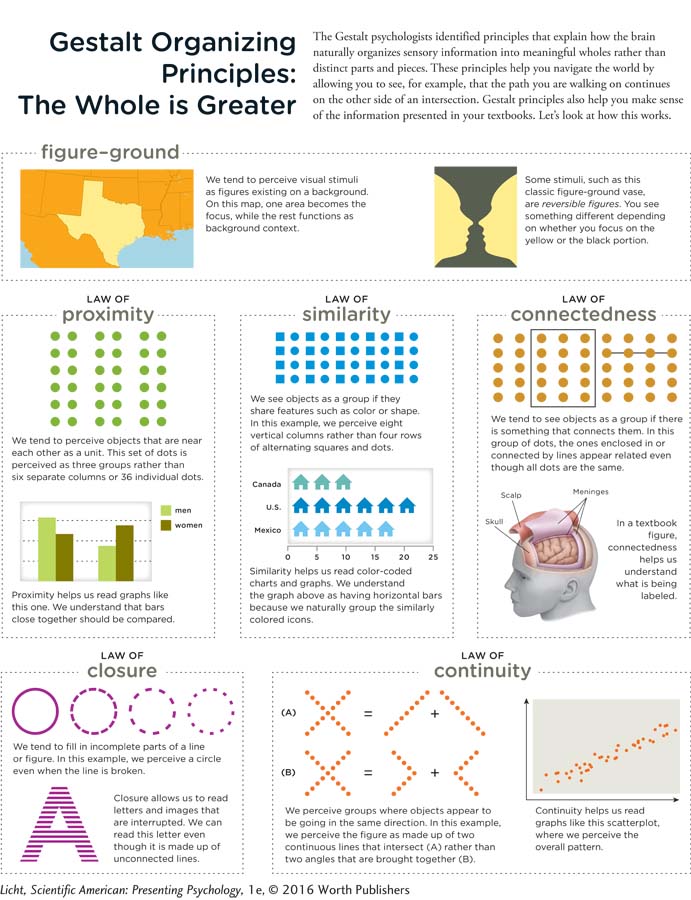

Many psychologists turn to the Gestalt (gə-ˈstält) psychologists to understand how perception works. Gestalt psychologists, who were active in Germany in the late 1800s and early 1900s, became interested in perception after observing illusions of motion. They wondered how stationary objects could be perceived as moving and thus attempted to explain how the human mind organizes stimuli in the environment. Noting the tendency for perception to be organized and complete, they realized that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts; the brain naturally organizes stimuli in their entirety rather than perceiving the parts and pieces. Gestalt means “whole” or “form” in German. The Gestalt psychologists, and others who followed, studied the principles that explain how the brain perceives objects in the environment as wholes or groups (Infographic 3.4, below).

INFOGRAPHIC 3.4

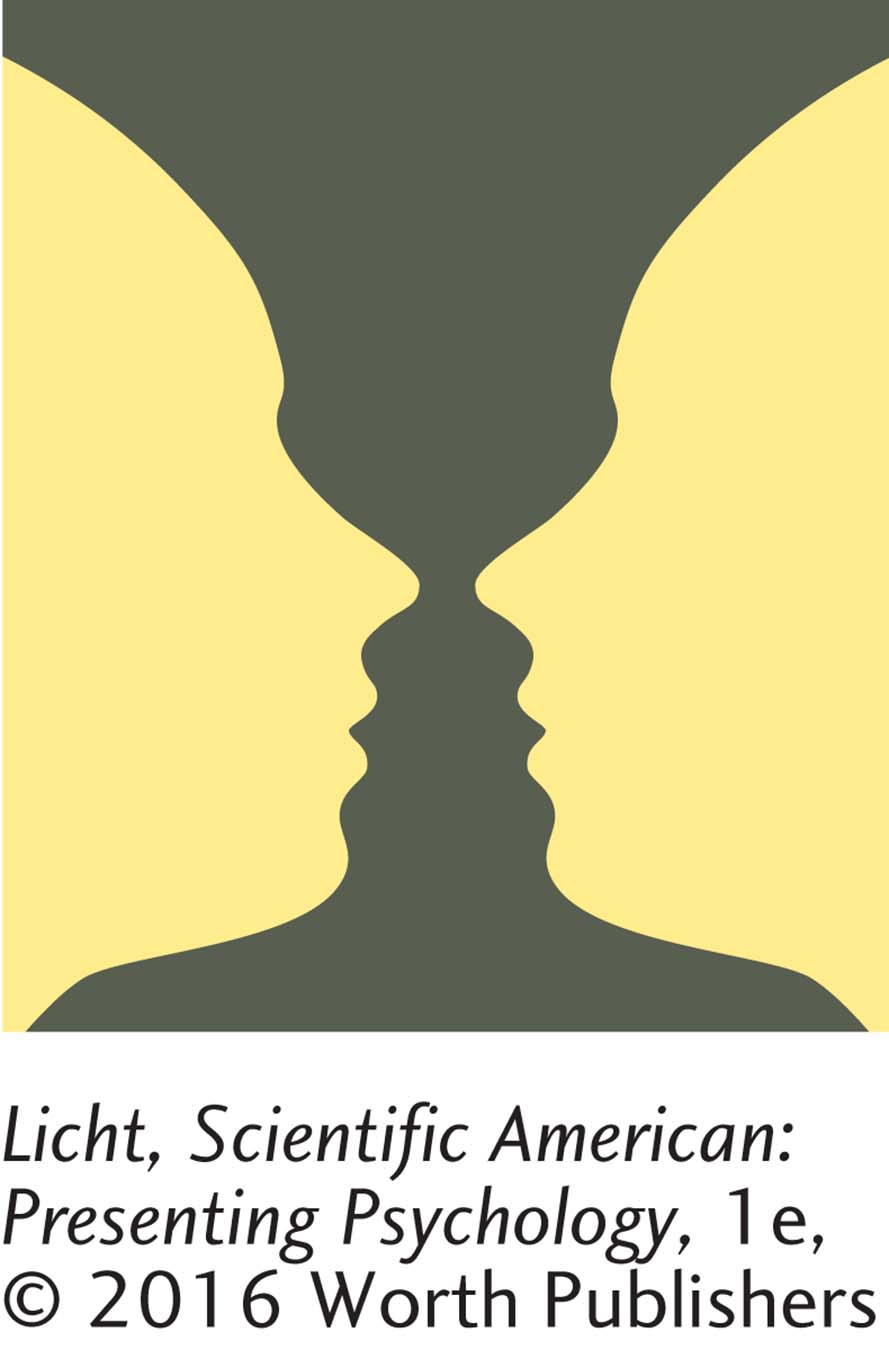

figure-

One central idea illuminated by the Gestalt psychologists is the figure-

Proximity—

Objects close to each other are perceived as a group. Similarity—

Objects similar in shape or color are perceived as a group. Connectedness—

Objects that are connected are perceived as a group. Closure—

Gaps tend to be filled in if something isn’t complete. Continuity—

Parts tend to be perceived as members of a group if they head in the same direction.

Although these organizational principles have been demonstrated for vision, it is important to note that they apply to the other senses as well. Imagine a mother who can discern her child’s voice amid the clamor of a busy playground: Her child’s voice is the figure and the other noises are the ground.

Depth Perception

LO 14 Identify concepts involved in depth perception.

That same mother can tell that the slide extends from the front of the jungle gym, thanks to her brain’s ability to pick up on cues about depth. How can a two-

A baby appears distressed when he encounters the visual cliff, a supportive glass surface positioned over a drop-

depth perception The ability to perceive three-

VISUAL CLIFF In order to determine whether depth perception is innate or learned, researchers studied the behavior of babies approaching a “visual cliff,” a flat, clear glass surface with a checkered tablecloth-

binocular cues Information gathered from both eyes to help judge depth and distance.

convergence A binocular cue used to judge distance and depth based on the tension of the muscles that direct where the eyes are focusing.

BINOCULAR CUES Some cues for perceiving depth are the result of information gathered by both eyes. Binocular cues provide information from the right and left eyes to help judge depth and distance. For example, convergence is the brain’s interpretation of the tension (or lack thereof) in the eye muscles that direct where both eyes focus. If an object is close, there is more muscular tension (as the muscles turn our eyes inward toward our nose), and the object is perceived as near. This perception of distance is based on experience; throughout life, we have learned that the more muscular tension, the closer an object. Let’s take a moment and feel that tension.

Point your finger up to the ceiling at arm’s length with both eyes open. Now slowly bring your finger close to your nose. Can you feel tension and strain in your eye muscles? Your brain uses this type of convergence cue to determine distance.

try this

retinal disparity A binocular cue that uses the difference between the images the two eyes see to determine the distance of objects.

Another binocular cue is retinal disparity, which is the difference between the images seen by the right and left eyes. The greater the difference, the closer the object. The more similar the two images, the farther the object. With experience, our brains begin using these image disparities to judge distance. The following Try This provides an example of retinal disparity.

Hold your index finger about 4 inches in front of your face pointing up to the ceiling. Quickly open your right eye as you are closing your left eye, alternating this activity for a few seconds; it should appear as if your finger is jumping back and forth. Now do the same thing, but this time with your finger out at arm’s length. The image does not seem to be jumping as much.

try this

You can gauge the distance and depth in this photo with at least four types of monocular cues: (1) People that are farther away look smaller (relative size). (2) The two sides of the street start out parallel but converge as distance increases (linear perspective). (3) The trees in the front block those that are behind (interposition). (4) Textures are more apparent for closer objects (texture gradient).

monocular cues Depth and distance cues that require the use of only one eye.

MONOCULAR CUES Judgments about depth and distance can also be informed by monocular cues, which do not necessitate the use of both eyes. An artist who paints pictures can transform a white canvas into a three-

Relative Size—

If two objects are similar in actual size, but one is farther away, it appears to be smaller. We interpret the larger object as being closer. Linear Perspective—

When two lines start off parallel, then come together, where they converge appears farther away than where they are parallel. Interposition—

When one object is in front of another, it partially blocks the view of the other object, and this partially blocked object appears more distant. Texture Gradient—

When objects are closer, it is easier to see their texture. As they get farther away, the texture becomes less visible. The more apparent the texture, the closer the object appears.

Perceptual Constancy and Perceptual Set

perceptual constancy The tendency to perceive objects in our environment as stable in terms of shape, size, and color, regardless of changes in the sensory data received.

shape constancy An object is perceived as maintaining its shape, regardless of the image projected on the retina.

size constancy An object is perceived as maintaining its size, regardless of the image projected on the retina.

color constancy Objects are perceived as maintaining their color, even with changing sensory data.

All these perceptual skills are great—

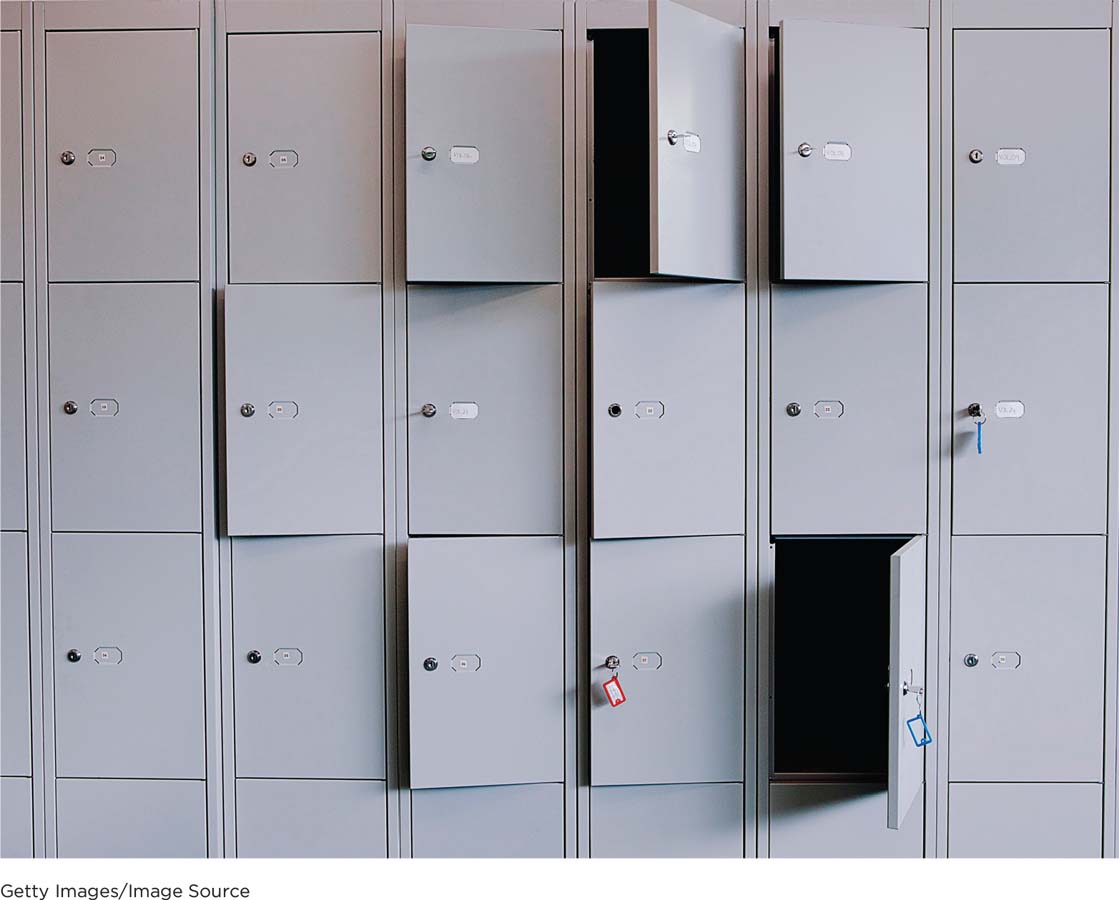

How do you know that all these doors are the same size and shape? The images projected onto your retina suggest that the opened doors are narrower, nonrectangular shapes. Your brain, however, knows from experience that all the opened doors are identical rectangles. This phenomenon is known as shape constancy.

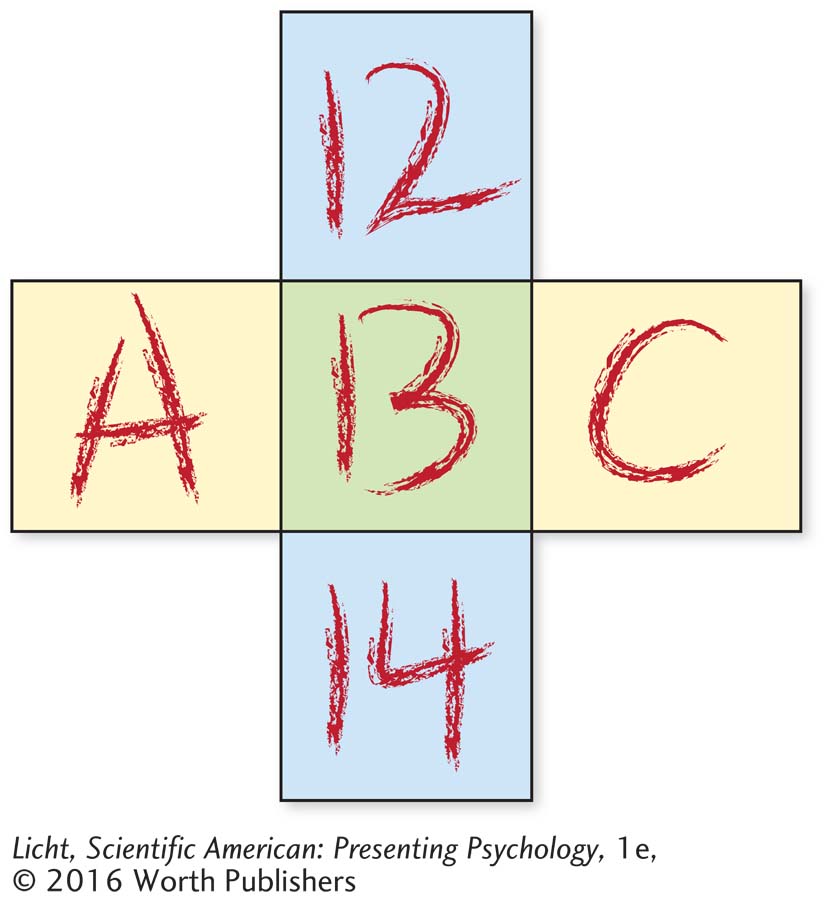

Look in the green square. What do you see? That depends on whether you viewed the symbol as belonging to a row of letters (A B C) or a column of numbers (12 13 14). Perceptions are shaped by the context in which a stimulus occurs, and our expectations about that stimulus.

Although examples of these organizational tendencies occur with robust regularity, some of these perceptual skills are not necessarily universal, as the Müller-

perceptual set The tendency to perceive stimuli in a specific manner based on past experiences and expectations.

Learning also plays a role in the phenomenon of perceptual set—the tendency to perceive stimuli in a specific manner based on past experiences and expectations. If someone handed you a picture of two women and said, “This is a mother with her daughter,” you would be more likely to rate them as looking alike than if you had been given the exact same picture and told, “These women are unrelated.” Indeed, research shows that people who believe they are looking at parent–

Perceptual sets are molded by the context of the moment. If you hear the word “sects” in a TV news report about feuding religious groups, you are unlikely to think the reporter is saying “sex” even though “sects” and “sex” sound the same. Similarly, if you see a baby swaddled in a blue blanket, you are probably more likely to assume it’s a boy than a girl. Studies show that expectancies about male or female infants influence viewers’ perceptions of gender (Stern & Karraker, 1989). Simply labeling infants as premature or full-

Although our perceptual sets may not always lead to the right conclusions, they do help us organize the vast amount of information flooding our senses. But can perception exist in the absence of sensation? In other words, is it possible to perceive something without seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, or feeling it?

Extrasensory Perception: Where’s the Evidence?

LO 15 Define extrasensory perception and explain why psychologists dismiss claims of its legitimacy.

extrasensory perception (ESP) The purported ability to obtain information about the world without any sensory stimuli.

parapsychology The study of extrasensory perception.

Have you ever had a dream that actually came to pass? Perhaps you have heard of psychics who claim that they can read people’s “auras” and decipher their thoughts. Extrasensory perception (ESP) is this purported ability to obtain information about the world without any sensory stimuli. And when we say “no sensory input,” we are not referring to sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and feelings occurring subliminally, or below absolute thresholds. We mean absolutely no measurable sensory data. The study of these kinds of phenomena is called parapsychology.

THINK again

Extrasensory Perception

ESP, psychic powers, the sixth sense—

ESP, psychic powers, the sixth sense—

CONNECTIONS

The importance of replicating experiments was discussed in Chapter 1. The more a study is replicated and produces similar findings, the more confident we can be in them; replication is a key step in the scientific method. If similar results cannot be reproduced using the same methods, then the original findings may have resulted from chance or experimenter bias.

. . . THERE IS NO SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE TO SUPPORT ITS EXISTENCE.

Despite ESP’s lack of scientific credibility, many people remain firm believers. Most often, their “evidence” comes in the form of personal anecdotes. Aunt Tilly predicted she was going to win the lottery based on a dream she had one night, and when she did win, it was “proof” of her ESP abilities. This is an example of what psychologists might call an illusory correlation, an apparent link between variables that are not closely related at all. Aunt Tilly dreamed she won the lottery, but so did 1,000 other people around the country, and they didn’t win—

Liz and her eldest daughter Sarah (back left) relax with the triplets: Zoe (front left), Emma (front right), and Sophie (back right). Zoe and Emma currently attend the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, while Sophie goes to school in the local district.

More interesting than ESP, we would argue, are the remarkable (and real) stories of people who thrive despite difficulties with sensation and perception. Are you wondering what became of Emma, Zoe, and Sophie?

MOVING FORWARD When the triplets were about 5 years old, Liz and her husband got a divorce, and Liz faced the daunting task of caring for four young children. Today, Sarah is a high school graduate, Emma and Zoe study at the prestigious Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, and Sophie is holding her own in the public school system. Liz operates her own business and recently wed her true love from two decades past.

MOVING FORWARD When the triplets were about 5 years old, Liz and her husband got a divorce, and Liz faced the daunting task of caring for four young children. Today, Sarah is a high school graduate, Emma and Zoe study at the prestigious Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, and Sophie is holding her own in the public school system. Liz operates her own business and recently wed her true love from two decades past.

With the love and support of family, Emma and Zoe have made significant strides in their social and linguistic skills. Both can communicate with about 50 signs, but they understand many more and are building their vocabulary all the time. As for Sophie, having limited vision has enabled her to take classes alongside sighted children.

show what you know

Question 1

1. ____________ means the “whole” or “form” in German.

Gestalt

Question 2

2. One binocular cue called ____________ is based on the brain’s interpretation of the tension in muscles of the eyes.

convergence

retinal disparity

interposition

relative size

a. convergence

Question 3

3. Using what you have learned so far in the textbook, how would you try to convince a friend that extrasensory perception does not exist?

ESP is the purported ability to obtain information about the world in the absence of sensory stimuli. There is a lack of scientific evidence to support the existence of ESP, and most so-

Question 4

4. Have you ever noticed how the shape of a door seems to change as it opens and closes, yet you know its actual shape remains the same? The term ____________ refers to the fact that even though sensory stimuli may change, we know that objects do not change their shape, size, or color.

perceptual set

perceptual constancy

convergence

texture-

gradient

b. perceptual constancy