4.2 Sleep

Matt Utesch was active and full of energy as a child, but come sophomore year in high school, he periodically fell asleep throughout the day. Matt was beginning to experience the symptoms of a serious sleep disorder.

ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL When Matt Utesch reminisces about childhood, he remembers having a lot of energy. “I was the kid that would wake up at 6:00 A.M. and watch cartoons,” Matt recalls. As a teenager, Matt channeled his energy through sports—

ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL When Matt Utesch reminisces about childhood, he remembers having a lot of energy. “I was the kid that would wake up at 6:00 A.M. and watch cartoons,” Matt recalls. As a teenager, Matt channeled his energy through sports—

At first it seemed like nothing serious. Matt just dozed off in class from time to time. But his mini-

It was the summer before junior year, and Matt was driving his truck home from work at his father’s appliance repair shop. One moment he was rolling along the street at a safe distance from other cars, and the next he was ramming into a brown Saturn that had slowed to make a left turn. What had transpired in the interim? Matt had fallen asleep. He slammed on the brake pedal, but it was too late; the two vehicles collided. Unharmed, Matt leaped out of his truck and ran to check on the other driver—

An Introduction to Sleep

Two mustang fillies sleep while standing. Horses are not the only animals that snooze in seemingly awkward positions. The bottlenose dolphin dozes while swimming, one brain hemisphere awake and the other asleep (McCormick, 2007; Siegel, 2005).

All animals sleep or engage in some rest activity that resembles sleep (Horne, 2006). Dolphins snooze while swimming, keeping one eye cracked open at all times; horses usually sleep standing up; and some birds appear to doze mid-

LO 4 Identify how circadian rhythm relates to sleep.

circadian rhythm (sər-

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM Have you ever noticed that you often get sleepy in the middle of the afternoon? Even if you had a good sleep the night before, you inevitably begin feeling tired around 2:00 or 3:00 P.M.; it’s like clockwork. That’s because it is clockwork. Many things your body does, including sleep, are regulated by a biological clock. Body temperature rises during the day, reaching its maximum in the early evening. Hormones are secreted in a cyclical fashion. Growth hormone is released at night, and the stress hormone cortisol soars in the morning, reaching levels 10 to 20 times higher than at night (Wright, 2002). These are just a few of the body functions that follow predictable daily patterns, affecting our behaviors, alertness, and activity levels. Such patterns in our physiological functioning roughly follow the 24-

In the circadian rhythm for sleep and wakefulness, there are two times when the desire for sleep hits hardest. The first is between 2:00 and 6:00 A.M., the same window of time when most car accidents caused by sleepiness occur (Horne, 2006). The second, less intense desire for sleep strikes midafternoon, around 2:30 P.M., when many college students have trouble keeping their eyes open in class (Mitler & Miller, 1996).

Not all biological rhythms are circadian. Some occur over longer time intervals (monthly menstruation), and others cycle much faster (90-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we explained the functions of the hypothalamus. For example, it maintains blood pressure, temperature, and electrolyte balance. It also is involved in regulating sleep–

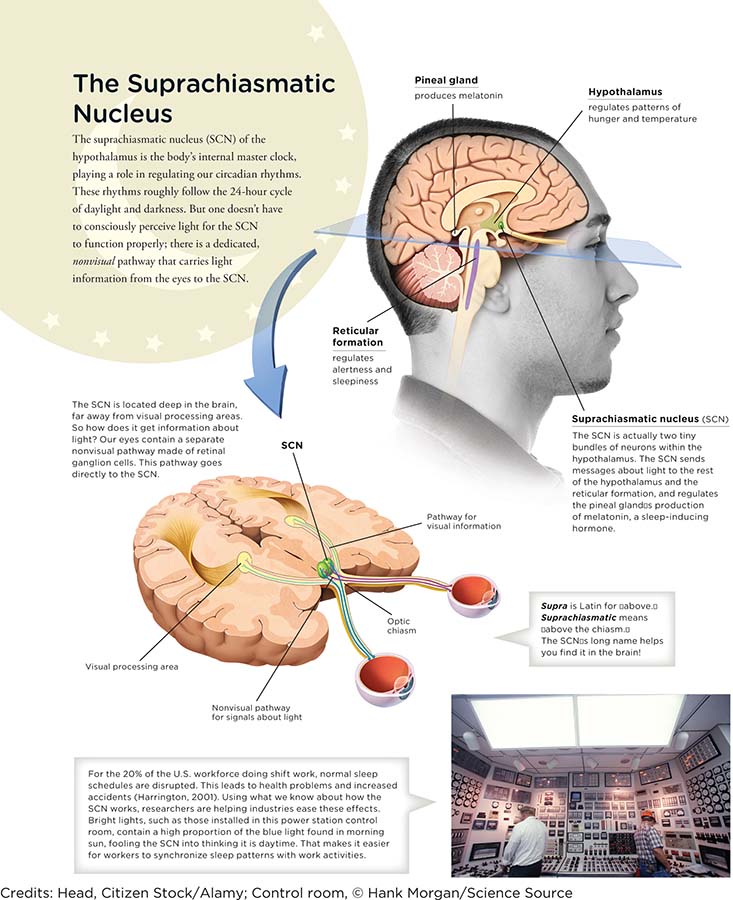

SUPRACHIASMATIC NUCLEUS Where in the human body do these inner clocks and calendars dwell? Miniclocks are found in cells all over your body, but a master clock is nestled deep within the hypothalamus, a brain structure whose activities revolve around maintaining homeostasis, or balance, in the body’s systems. This master of clocks, known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), actually consists of two clusters, each no bigger than an ant, totaling around 20,000 neurons (Forger & Peskin, 2003; Wright, 2002). The SCN plays a role in our circadian rhythm by communicating with other areas of the hypothalamus, which regulates daily patterns of hunger and temperature, and the reticular formation, which regulates alertness and sleepiness (Infographic 4.1).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we described how light enters the eye and is directed to the retina. The rods and cones in the retina are photoreceptors, which absorb light energy and turn it into electrical and chemical signals. Here, we see how light-

Although tucked away in the recesses of the brain, the SCN knows the difference between day and night. That’s because it receives signals from a special type of light-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we presented the experiences of the 33 Chilean miners who spent 2 months trapped in the dark caverns of a collapsed mine. When they were rescued, actions were taken to protect their eyes because they had not been exposed to natural light for more than 2 months.

What would happen if you lived in a dark cave with no cell phones or computers to help you keep track of time? Would your body stay on a 24-

INFOGRAPHIC 4.1

LARKS AND OWLS Everyone has her own unique clock, which helps explain why some of us are “morning people” or so-

College students are often portrayed as owls, but is this just a stereotype? Does something in the college environment influence sleep–

try this

JET LAG AND SHIFT WORK Whether you are a lark or an owl, your biological clock is likely to become confused when you travel across time zones. Your clock does not automatically reset to match the new time. The physical and mental consequences of this delayed adjustment, known as “jet lag,” may include difficulty concentrating, headaches, and gastrointestinal distress. Fortunately, the biological clock can readjust by about 1 or 2 hours each day, eventually falling into step with the new environmental schedule (Cunha & Stöppler, 2011). Jet lag is frustrating, but at least it’s only temporary.

Rapidly traveling through time zones puts a strain on the body and brain. Most of us can adjust by 1 or 2 hours per day. So if you travel across 3 time zones (Los Angeles to New York), it could take as long as 3 days to adapt (Cunha & Stöppler, 2011).

Factory workers are among the many professionals who clock in and out at all hours of the day. Working alternating or night shifts can disrupt circadian rhythms, leading to fatigue, irritability, and diminished mental sharpness. Physical activity and good sleep habits will help counteract the negative effects (Costa, 2003).

Now imagine plodding through life with a case of jet lag you just can’t shake. This is the tough reality for some of the world’s shift workers—

Dr. Lawrence J. Epstein of Harvard Medical School suggests ways in which night workers can minimize circadian disturbances and increase their productivity. Remember that light is the master clock’s most important external cue. Dr. Epstein suggests maximizing light exposure during work time and steering clear of it close to bedtime. Some night shifters don sunglasses on their way home, to block the morning sun, and head straight to bed in a quiet, dark room (Epstein & Mardon, 2007). Taking 20-

The Stages of Sleep

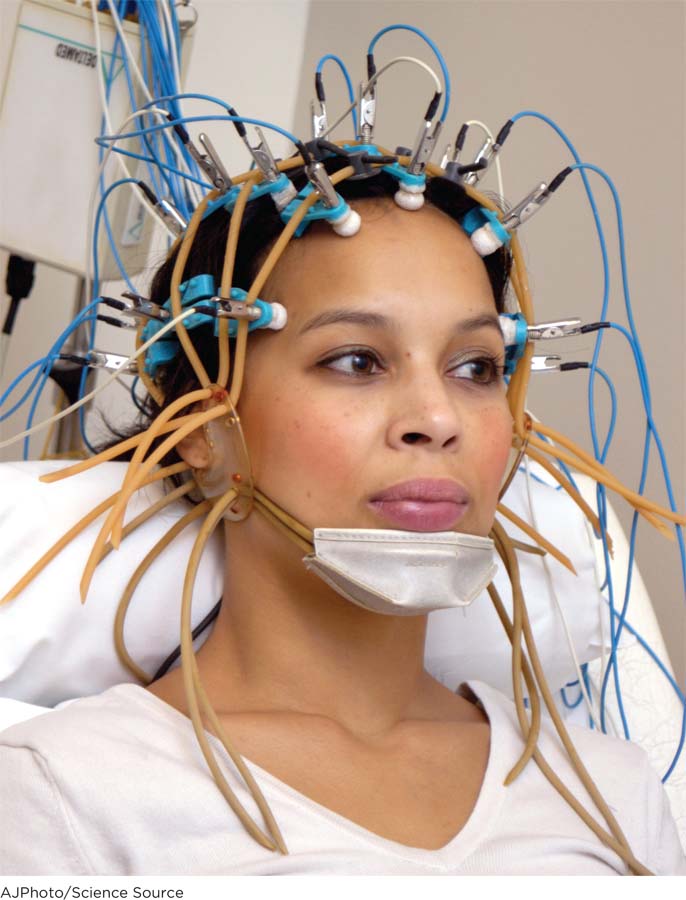

A woman receives an electro-

LO 5 Summarize the stages of sleep.

beta waves Brain waves that indicate an alert, awake state.

alpha waves Brain waves that indicate a relaxed, drowsy state.

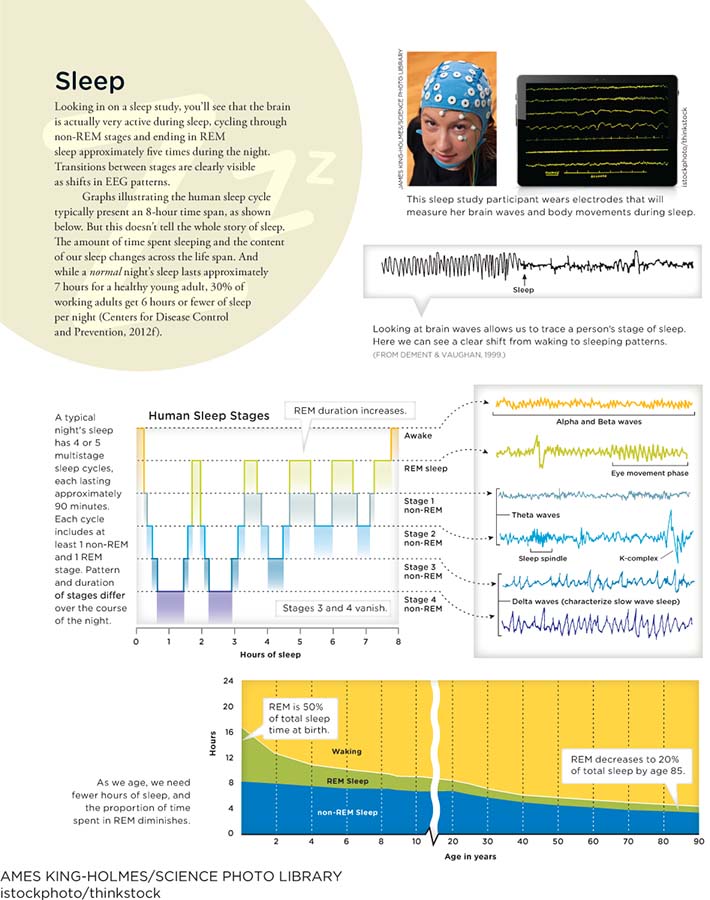

Have you ever watched someone sleeping? The person looks blissfully tranquil: body still, face relaxed, chest rising and falling like a lazy ocean wave. Don’t be fooled. Underneath the body’s quiet front is a very active brain, as revealed by an electroencephalogram (EEG), a device that picks up electrical signals from the brain and displays this information on a screen. If you could look at an EEG trace of your brain right this moment, you would probably see a series of tiny, short spikes in rapid-

non-

theta waves Brain waves that indicate light sleep.

NON-

INFOGRAPHIC 4.2

istockphoto/thinkstock

After a few minutes in Stage 1, you move on to the next phase of non-

delta waves Brain waves that indicate a deep sleep.

After passing through Stages 1 and 2, the sleeper descends into Stage 3, and then into an even deeper Stage 4, when it is most difficult to awaken. Both Stages 3 and 4 are known as slow-

rapid eye movement (REM) The stage of sleep associated with dreaming; sleep characterized by bursts of eye movements, with brain activity similar to that of a waking state, but with a lack of muscle tone.

This cat may be dreaming of chasing mice and birds, but its body is essentially paralyzed during REM sleep. Disable the neurons responsible for this paralysis and you will see some very interesting behavior—

REM SLEEP You don’t stay in deep sleep for the remainder of the night, however. After about 40 minutes of Stage 4 sleep, you work your way back through the lighter stages of sleep, from Stage 4, to Stage 3, to Stage 2, and finally to Stage 1. Then, instead of waking up, you enter a fifth stage known as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. During REM, the eyes often dart around, even though they are closed (hence the name “rapid eye movement” sleep). The brain is very active, with EEG recordings showing faster and shorter waves similar to that of someone who is wide awake. Pulse and breathing rate fluctuate, and blood flow to the genitals increases, which explains why people frequently wake up in a state of sexual arousal. Another name for REM sleep is paradoxical sleep, because the sleeper appears to be quiet and resting, but the brain is full of electrical activity. People roused from REM sleep often report having vivid, illogical dreams. Thankfully, the brain has a way of preventing us from acting out our dreams. During REM sleep, certain neurons in the brainstem control the voluntary muscles, keeping most of the body still.

What would happen if the neurons responsible for disabling the muscles during REM sleep were destroyed or damaged? Researchers led by Michel Jouvet in France and Adrian Morrison in the United States found the answer to that question in the 1960s and 1970s. Both teams showed that severing these neurons in the brains of cats caused them to act out their kitty dreams. Not only did the sleeping felines stand up; they arched their backs in fury, groomed and licked themselves, and hunted imaginary mice (Jouvet, 1979; Sastre & Jouvet, 1979).

SLEEP ARCHITECTURE Congratulations. You have just completed one sleep cycle, working your way through Stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 of non-

As we age, the makeup of our sleep cycles, or sleep architecture, changes. Older people spend less time in REM sleep and the deeply refreshing stages of non-

Nature and Nurture

What Kind of Sleeper Are You?

On a typical weeknight, the average American sleeps 6 hours and 40 minutes, but there is significant deviation from this “average.” A large number of people—

On a typical weeknight, the average American sleeps 6 hours and 40 minutes, but there is significant deviation from this “average.” A large number of people—

Some of us feel refreshed after sleeping 6 or 7 hours. Others can barely grasp a glass of orange juice without a solid 8. Sleep habits appear to be a blend of biological and environmental forces—

When it comes to understanding sleep patterns, we cannot ignore what is in our nature, or genetics. Some studies suggest sleep needs are inherited from parents, and there are probably many genes involved (He et al., 2009; Hor & Tafti, 2009). Evidence also suggests that “short sleepers” (people who average fewer than 6 hours per night) and “long sleepers” (those who sleep more than 9 hours) are running on different circadian rhythms. Nighttime increases of the “sleep hormone” melatonin, for example, tend to be reduced for those who get fewer zzz’s (Aeschbach et al., 2003; Rivkees, 2003).

ARE “SHORT SLEEPERS” ALWAYS IN SLEEP DEBT?

But it is also possible that some short sleepers are really just average sleepers getting by on less than an optimal amount of sleep. Given the opportunity to catch up for a few days, would they sleep for hours upon hours? This is just what happened in a small study of healthy young adults. On Day 1 of sleep catch-

Sleep Disturbances

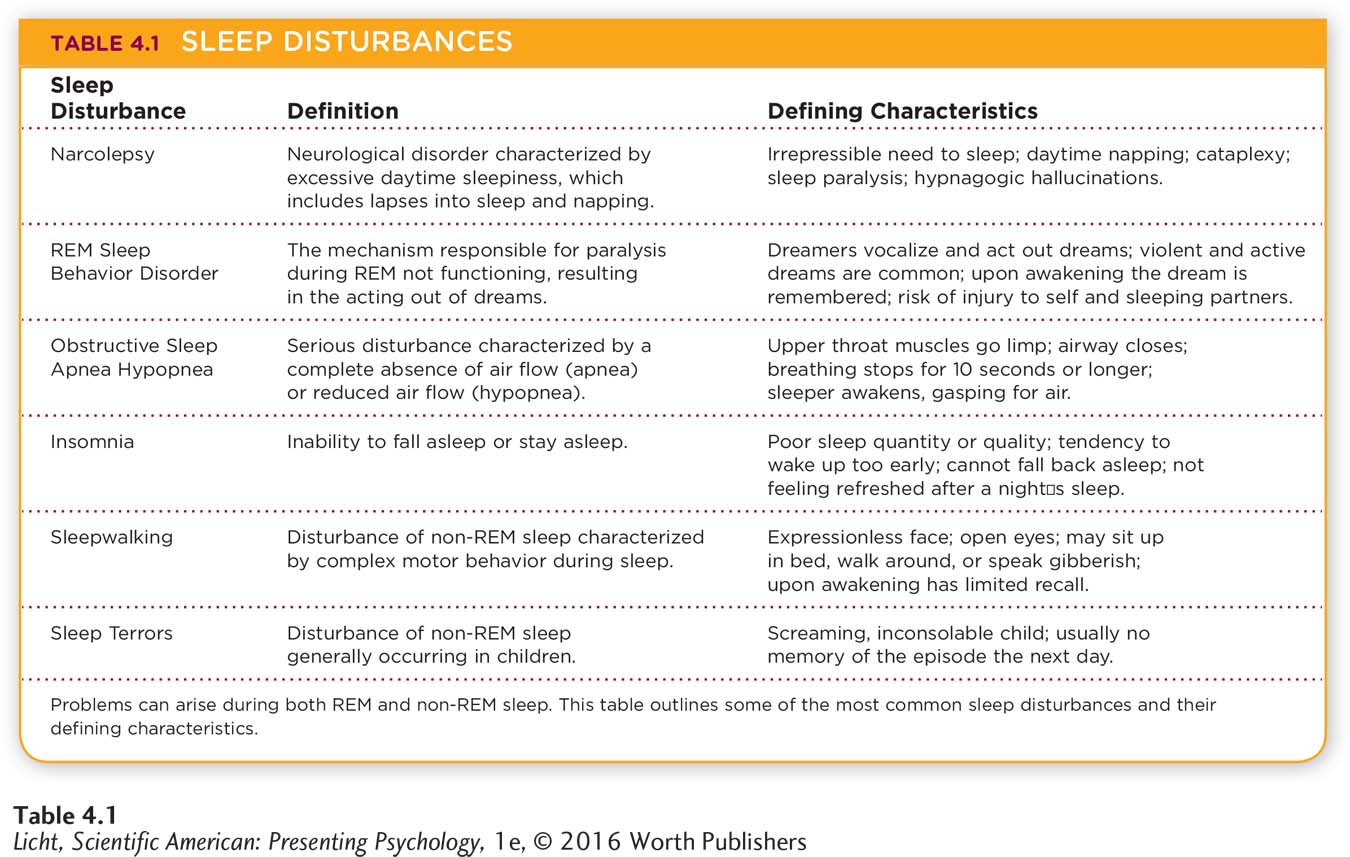

LO 6 Recognize various sleep disorders and their symptoms.

narcolepsy A neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness, which includes lapses into sleep and napping.

Matt’s battle with narcolepsy climaxed during his junior year of high school. In addition to falling asleep 20 to 30 times a day, he was experiencing frequent bouts of cataplexy, an abrupt loss of muscle tone that occurs while one is awake. Cataplexy struck Matt anytime, anywhere—

PROBLEM IDENTIFIED: NARCOLEPSY Shortly after the car accident, Matt was diagnosed with narcolepsy, a neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and other sleep-

PROBLEM IDENTIFIED: NARCOLEPSY Shortly after the car accident, Matt was diagnosed with narcolepsy, a neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and other sleep-

CATAPLEXY And that wasn’t all. Matt developed another debilitating symptom of narcolepsy: cataplexy, an abrupt loss of strength or muscle tone that occurs when a person is awake. During a severe cataplectic attack, some muscles go limp, and the body may collapse slowly to the floor like a rag doll. One moment Matt would be standing in the hallway laughing with friends; the next he was splayed on the floor unable to move a muscle. “It was like a tree being cut down [and] tipping over,” he recalls. Cataplexy attacks come on suddenly, usually during periods of emotional excitement (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The effects usually wear off after several seconds, but severe attacks can render a person immobilized for minutes.

Eight-

Cataplexy may completely disable the body, but it produces no loss in consciousness. Even during the worst attack, Matt remained completely aware of himself and his surroundings. He could hear people talking about him; sometimes they snickered in amusement. “Kids can be cruel,” Matt says. By junior year, Matt was having 60 to 100 attacks a day.

SLEEP PARALYSIS AND HYPNAGOGIC HALLUCINATIONS Matt also developed two other common narcolepsy symptoms: sleep paralysis and hypnagogic hallucinations. Sleep paralysis is a temporary paralysis that strikes just before falling asleep or upon waking (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Recall that the body becomes paralyzed during REM sleep, but sometimes this paralysis sets in prematurely or fails to turn off on time. Picture yourself lying in bed, awake and fully aware yet unable to roll over, climb out of bed, or even wiggle a toe. You want to scream for help, but your lips won’t budge. Sleep paralysis is a common symptom of narcolepsy, but it can also strike ordinary sleepers. One study found that nearly a third of college students had experienced sleep paralysis at least once in their lives (Cheyne, Newby-

Sleep paralysis may seem scary, but now imagine seeing bloodthirsty vampires standing at the foot of your bed just as you are about to fall asleep. Earlier we discussed the hypnagogic hallucinations people can experience during Stage 1 sleep (seeing strange images, for example). But not all hypnagogic hallucinations involve harmless blobs. They can also be realistic visions of axe murderers or space aliens trying to abduct you (McNally & Clancy, 2005). Matt had a recurring hallucination of a man with a butcher knife racing through his doorway, jumping onto his bed, and stabbing him in the chest. Upon awakening, Matt would often quiz his mother with questions like, “When is my birthday?” or “What is your license plate number?” He wanted to verify she was real, not just another character in his dream. Like sleep paralysis, vivid hypnagogic hallucinations can occur in people without narcolepsy, too. Shift work, insomnia, and sleeping faceup are all factors that appear to heighten one’s risk (Cheyne, 2002; McNally & Clancy, 2005).

BATTLING NARCOLEPSY Throughout junior year, Matt took various medications to control his narcolepsy, but his symptoms persisted. Narcolepsy was beginning to interfere with virtually every aspect of his life. At the beginning of high school, Matt had a 4.0 grade point average; now he was working twice as hard and earning lower grades. Playing sports had become a major health hazard because his cataplexy struck wherever and whenever, without notice. If he collapsed while sprinting down the soccer field or diving for a basketball, he might twist an ankle, break an arm, or worse. It was during this time that Matt realized who his true friends were. “The people that stuck with me [then] are still my close friends now,” he says. Matt’s loyal buddies learned to recognize the warning signs of his cataplexy (for example, when he suddenly stands still and closes his eyes) and did everything possible to keep him safe, grabbing hold of his body and slowly lowering him to the ground. His buddies had his back—

Approximately 1 in 2,500 people suffers from narcolepsy (Ohayon, 2011). It is believed to result from a failure of the brain to properly regulate sleep patterns. Normally, the boundaries separating sleep and wakefulness are relatively clear—

REM sleep behavior disorder A sleep disturbance in which the mechanism responsible for paralyzing the body during REM sleep is not functioning, resulting in the acting out of dreams.

REM SLEEP BEHAVIOR DISORDER Problems with REM regulation can also lead to other sleep disturbances, including REM sleep behavior disorder. The defining characteristics of this disorder include “repeated episodes of arousal often associated with vocalizations and/or complex motor behaviors arising from REM sleep” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 408). People with REM sleep behavior disorder are much like the cats in Morrison’s and Jouvet’s experiments; something has gone awry with the brainstem mechanism responsible for paralyzing their bodies during REM sleep, so they are able to move around and act out their dreams (Schenck & Mahowald, 2002). This is not a good thing, since the dreams of people with REM sleep behavior disorder tend to be unusually violent and action-

obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea (hī-pop-

Actor and TV personality Rosie O’Donnell is among the millions of Americans who suffer from obstructive sleep apnea (Schocker, 2012, September 25). Research suggests this sleep disorder affects between 3% and 7% of the adult population (Punjabi, 2008).

BREATHING-

insomnia Sleep disorder characterized by an inability to fall asleep or stay asleep, impacting both the quality and the quantity of sleep.

INSOMNIA The most prevalent sleep disorder is insomnia, which is characterized by an inability to fall asleep or stay asleep. People with insomnia often report that the quantity or quality of their sleep is not good. They may complain of waking up in the middle of the night or arising too early, and not being able to fall back asleep. Sleepiness during the day and difficulties with cognitive tasks are also reported (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). About a third of adults experience some symptoms of insomnia, and 6% to 10% suffer from insomnia disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Mai & Buysse, 2008; Roth, 2007). Insomnia symptoms can be related to many factors, including the stress of a new job, college studies, depression, anxiety, jet lag, aging, and drug use.

Pop diva Lady Gaga glows at the Vanity Fair Oscar Party in 2014. Gaga appears to get plenty of beauty sleep, but she reportedly suffers from insomnia. “Fame is like rocket fuel,” she said in a 2010 interview with OK! magazine. “The more my fans like what I’m doing, the more I want to give back to them. And my passion is so strong I can’t sleep. I haven’t slept for three days” (Simpson, 2010, April 5, para. 3).

OTHER SLEEP DISTURBANCES A common sleep disturbance that can occur during non-

Synonyms

sleep terrors night terrors

sleepwalking somnambulism (säm-

sleep terrors A disturbance of non-

Sleep terrors are non-

nightmares Frightening dreams that occur during REM sleep.

Nightmares are frightening dreams that occur in REM sleep. They affect people of all ages. And unlike night terrors, nightmares can often be recalled in vivid detail. Because nightmares usually occur during REM sleep, they are generally not acted out (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

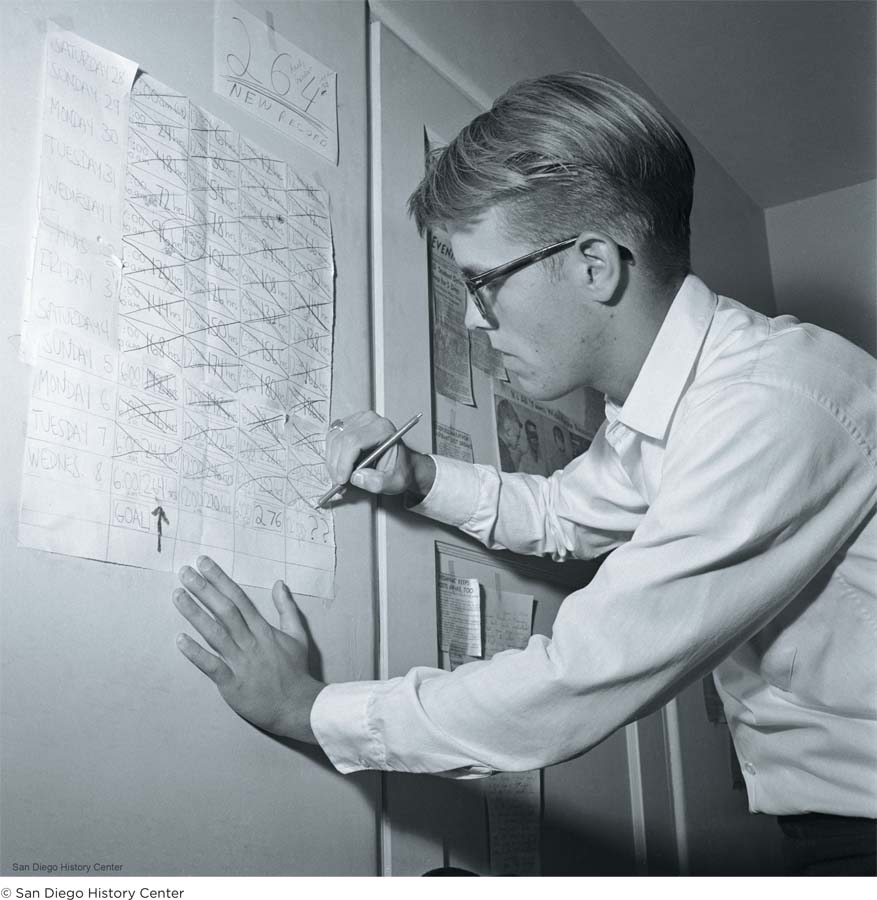

Who Needs Sleep?

Matt’s worst struggle with narcolepsy stretched through the last two years of high school. During this time, he was averaging 20 to 30 naps a day. You might think that someone who falls asleep so often would at least feel well rested while awake. This was not the case. Matt had trouble sleeping at night, and it was taking a heavy toll on his ability to think clearly. He remembers nodding off at the wheel a few times but continuing to drive, reassuring himself that everything was fine. He forgot about homework assignments and simple things people told him. Matt was experiencing two of the most common symptoms of sleep deprivation: impaired judgment and lapses in memory (Goel, Rao, Durmer, & Dinges, 2009).

Let’s face it. No one can function optimally without a good night’s sleep. But the expression “good night’s sleep” means something quite different from one person to the next. Newborns sleep anywhere from 10.5 to 18 hours per day, toddlers 11 to 14 hours, school-

A rickshaw driver snoozes in the bright sun. Afternoon siestas are common in countries such as India and Spain, but atypical in the United States (Randall, 2012, September 22). Cultural norms regarding sleep vary significantly around the world.

SLEEP DEPRIVATION What happens to animals when they don’t sleep at all? Laboratory studies show that sleep deprivation kills rats faster than starvation (Rechtschaffen & Bergmann, 1995; Siegel, 2005). Curtailing sleep in humans leads to rapid deterioration of mental and physical well-

A half-

A more chronic form of sleep deprivation results from insufficient sleep night-

REM DEPRIVATION So far we have only covered sleep loss in general, but remember there are two types of sleep: REM and non-

REM rebound An increased amount of time spent in REM during the first sleep session after sleep deprivation.

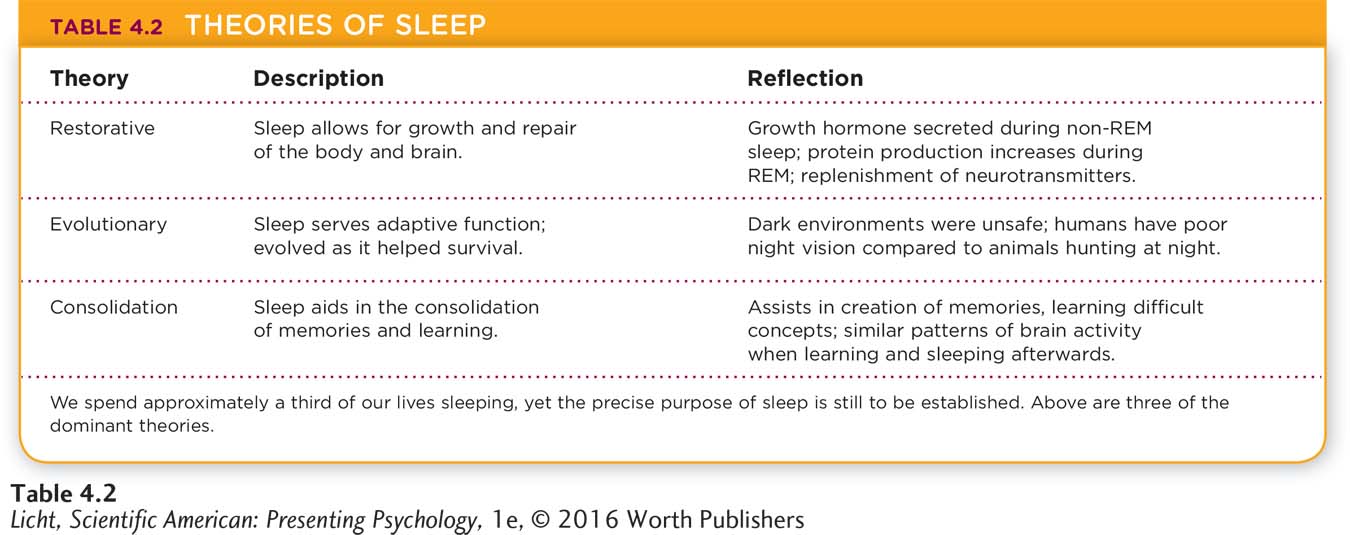

WHY DO WE SLEEP? The exact purpose of sleep has yet to be identified. Drawing from sleep deprivation studies and other types of experiments, researchers have constructed various theories to explain why we spend so much time sleeping (Table 4.2). Here are three of the major ones:

The restorative theory says we sleep because it allows for growth and repair of the body and brain. Growth hormone is secreted during non-

REM sleep and protein production ramps up in the brain during REM. Some have suggested that sleep is a time for rest and replenishment of neurotransmitters, especially those important for attention and memory (Hobson, 1989). An evolutionary theory says sleep serves an adaptive function; it evolved because it helped us survive. For much of human history, nighttime was very dark—

and very unsafe. Humans have poor night vision compared to animals hunting for prey, so it was adaptive for us to avoid moving around our environments in the dark of night. The development of our circadian rhythms driving us to sleep at night has served an important evolutionary purpose. Another compelling theory suggests that sleep helps with the consolidation of memories and learning. Researchers disagree about which stage of sleep might facilitate such a process, but one thing seems clear: Without sleep, our ability to lay down complex memories, and thus learn difficult concepts, is hampered (Farthing, 1992). Studies show that areas of the brain excited during learning tasks are reawakened during non-

REM sleep. When researchers monitored the neuronal activity of rats exploring a new environment, they noticed certain neurons firing. These same neurons became active again when the rats fell into non- REM sleep, suggesting that the neurons were involved in remembering the experience (Diekelmann & Born, 2010). Similarly, in humans, PET scans have shown common patterns of brain activity when research participants were awake and learning and later while asleep (Maquet, 2000).

Whatever the purpose of sleep, there is no denying its importance. After a couple of sleepless nights, we are grumpy, clumsy, and unable to think straight. Although we may appreciate the value of sleep, we don’t always practice the best sleep habits—

Apply This

7 Sleep Myths

Everyone seems to have their own bits of “expert knowledge” about sleep. Read on to learn about claims (in bold) that are false.

Drinking alcohol before bed helps you sleep better: Alcohol helps you fall asleep, but it undermines sleep quality and may cause you to awaken in the night (Ebrahim, Shapiro, Williams, & Fenwick, 2013). So, too, can one or two cups of coffee. Although moderate caffeine consumption heightens alertness (Epstein & Mardon, 2007), be careful not to drink too much or too close to bedtime; either action may lead to further sleep disruption (Drake, Roehrs, Shambroom, & Roth, 2013).

Exercising right before bed sets you up for a good night’s sleep: Generally speaking, exercise promotes slow-

wave sleep, the type that makes you feel bright- eyed and bushy- tailed in the morning (Driver & Taylor, 2000; Youngstedt & Kline, 2006). However, working out too close to bedtime (2 to 3 hours beforehand) may prevent good sleep (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2012). Everyone needs 8 hours of sleep each night: Most people require between 7 and 8 hours (Banks & Dinges, 2007), but sleep needs can range greatly from person to person. Some people do fine with 6 hours; others genuinely need 9 or 10.

Watching TV or using your computer just before bed helps get you into the sleep zone: Screen time is not advised as a transition into sleep time. The stimulation of TV and computers can inhibit sleep (National Sleep Foundation, 2015b).

You can catch up on accumulated sleep loss with one night of “super-

sleep”: Settling any sleep debt is not easy. You may feel refreshed upon waking from 10 hours of “recovery” sleep, but the effects of sleep debt will likely creep up later on (Cohen et al., 2010).Insomnia is no big deal. Everyone has trouble sleeping from time to time: Insomnia is a mentally and physically debilitating condition that can result in mood changes, memory problems, difficulty with concentration and coordination, and other life-

altering impairments (Pavlovich- Danis & Patterson, 2006). NO IPADS ALLOWED IN THE BED!

Sleep aids are totally safe: When taken according to prescription, sleep aids are relatively safe and effective, although they do not guarantee a normal night of sleep. That being said, research has linked some of these medications to an increased risk of death (Kripke, Langer, & Kline, 2012), as well as an increased risk of sleep eating, sleep sex, and “driving while not fully awake” (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2013, para. 5).

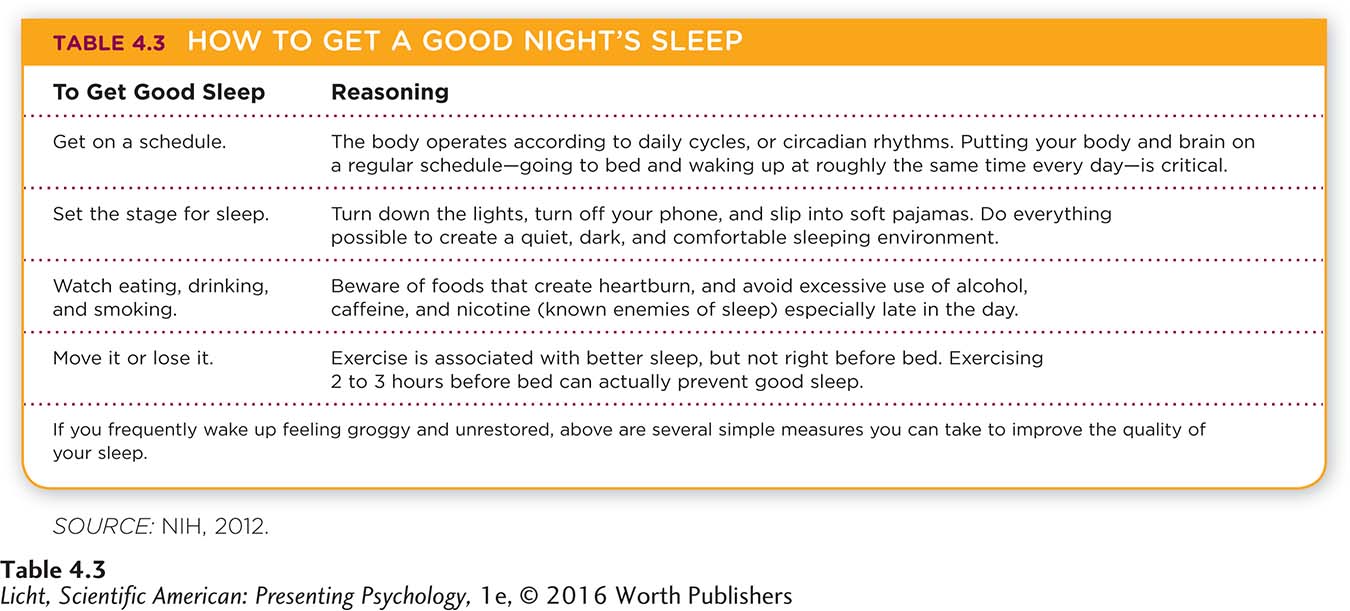

Before moving on to the next section, look at Table 4.3, below for some ideas on how to get better sleep.

show what you know

Question 1

1. The suprachiasmatic nucleus obtains its information about day and night from:

circadian rhythms.

beta waves.

K-

complexes. retinal ganglion cells.

d. retinal ganglion cells.

Question 2

2. In which of the following stages of sleep do adults spend the most time at night?

Stage 1

Stage 2

Stage 3

Stage 4

b. Stage 2

Question 3

3. Narcolepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and other sleep-

cataplexy

Question 4

4. Make a drawing of the 90-

Drawings will vary; see Infographic 4.2. A normal adult sleeper begins in non-