4.3 Dreams

Sleep is an exciting time for the brain. As we lie in the darkness, eyes closed and bodies limp, our neurons keep firing. REM is a particularly active sleep stage, characterized by brain waves that are fast and irregular. During REM, anything is possible. We can soar through the clouds, kiss superheroes, and ride roller coasters with frogs. Time to explore the weird world of dreaming.

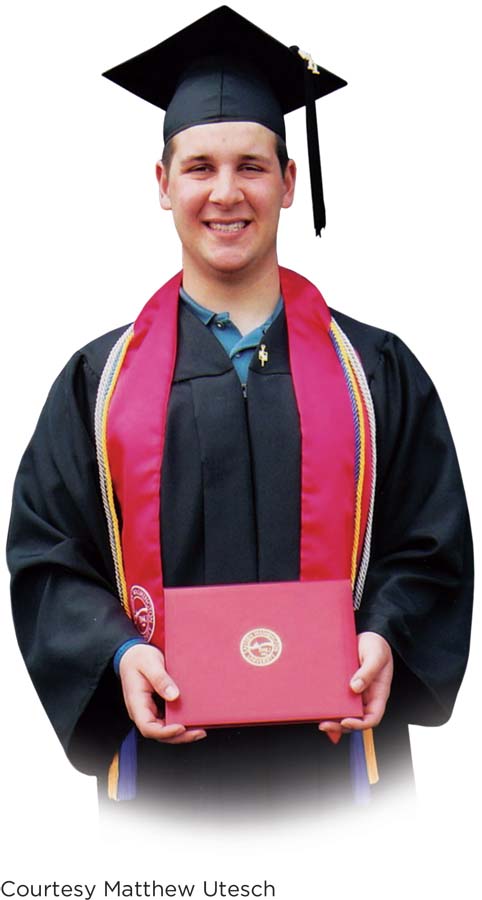

After a few very challenging years, Matt developed effective strategies for managing his narcolepsy. In addition to using a medication that helps him sleep more soundly at night, Matt takes strategic power naps and sticks to a regular bedtime and wake-

SLEEP, SLEEP, GO AWAY Just 2 months before graduating from high school, Matt began taking a new medication that vastly improved the quality of his nighttime sleep. He also began strategic power napping, setting aside time in his schedule to go somewhere peaceful and fall asleep for 15 to 30 minutes. “Power naps are probably the greatest thing a person with narcolepsy can do,” Matt insists. The naps helped eliminate the daytime sleepiness, effectively preempting all those unplanned naps that had fragmented his days. Matt also worked diligently to create structure in his life, setting a predictable rhythm of going to bed, taking medication, going to bed again, waking up in the morning, attending class, taking a nap, and so on.

SLEEP, SLEEP, GO AWAY Just 2 months before graduating from high school, Matt began taking a new medication that vastly improved the quality of his nighttime sleep. He also began strategic power napping, setting aside time in his schedule to go somewhere peaceful and fall asleep for 15 to 30 minutes. “Power naps are probably the greatest thing a person with narcolepsy can do,” Matt insists. The naps helped eliminate the daytime sleepiness, effectively preempting all those unplanned naps that had fragmented his days. Matt also worked diligently to create structure in his life, setting a predictable rhythm of going to bed, taking medication, going to bed again, waking up in the morning, attending class, taking a nap, and so on.

Now a college graduate and working professional, Matt manages his narcolepsy quite successfully. All of his major symptoms—

Not everyone with narcolepsy is so fortunate. The disorder is often mistaken for another ailment, such as depression or insomnia. Most people with narcolepsy don’t even know they have it, and by the time an expert offers them a diagnosis (sometimes years after the symptoms began), they have already suffered major social and professional consequences (Stanford School of Medicine, 2015). While several medications are available to help control symptoms, there is no known cure for narcolepsy. Scheduling “therapeutic naps,” avoiding monotonous activities, and controlling emotional highs are all behavioral treatments for narcolepsy.

Now when Matt goes to sleep at night, he no longer imagines people coming to murder him. In dreams, he soars through the skies like Superman, barreling into outer space to visit the planets. “All my dreams are now pleasant,” says Matt, “[and] it’s a lot nicer being able to fly than being stabbed by a butcher knife.” If you wonder what Matt is doing these days, he works at a credit union (one of the top producers in his company) and is pursuing his master's of business administration (MBA). Onward and upward, like Superman.

In Your Dreams

LO 7 Summarize the theories of why we dream.

What are dreams, and why do we have them? People have contemplated the significance of dreams for millennia, and scholars have developed many intriguing theories to explain them.

manifest content The apparent meaning of a dream; the remembered story line of a dream.

latent content The hidden meaning of a dream, often concealed by the manifest content of the dream.

activation–

PSYCHOANALYSIS AND DREAMS The first comprehensive theory of dreaming was developed by the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud (Chapters 10 and 13). In 1900 Freud laid out his theory in the now-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3 we noted that the vestibular system is responsible for our balance. Accordingly, if its associated area in the nervous system is active while we are asleep, the sensations normally associated with this system when we are awake will be interpreted in a congruent manner.

ACTIVATION–

NEUROCOGNITIVE THEORY OF DREAMS The neurocognitive theory of dreams proposes that a network of neurons exists in the brain, including some areas in the limbic system and the forebrain, that is necessary for dreaming to occur (Domhoff, 2001). People with damage to these brain areas either do not have dreams, or their dreams are not normal. Additional support for this theory comes from studies of children; it turns out that the dreams of children differ from those of adults. Before about 13 to 15 years of age, children report dreams that are less vivid and seem to have less of a story line. Apparently, an underlying neural network must develop or mature before a child can dream like an adult. And as noted earlier, memory consolidation seems to be facilitated by sleep, with some theorists emphasizing the important role REM sleep plays in this process. The neurocognitive theory of dreams does not suggest, however, that dreams serve a purpose. Instead, they seem to be the result of how sleep and consciousness have evolved in humans (Domhoff, 2001).

Dream a Little Dream

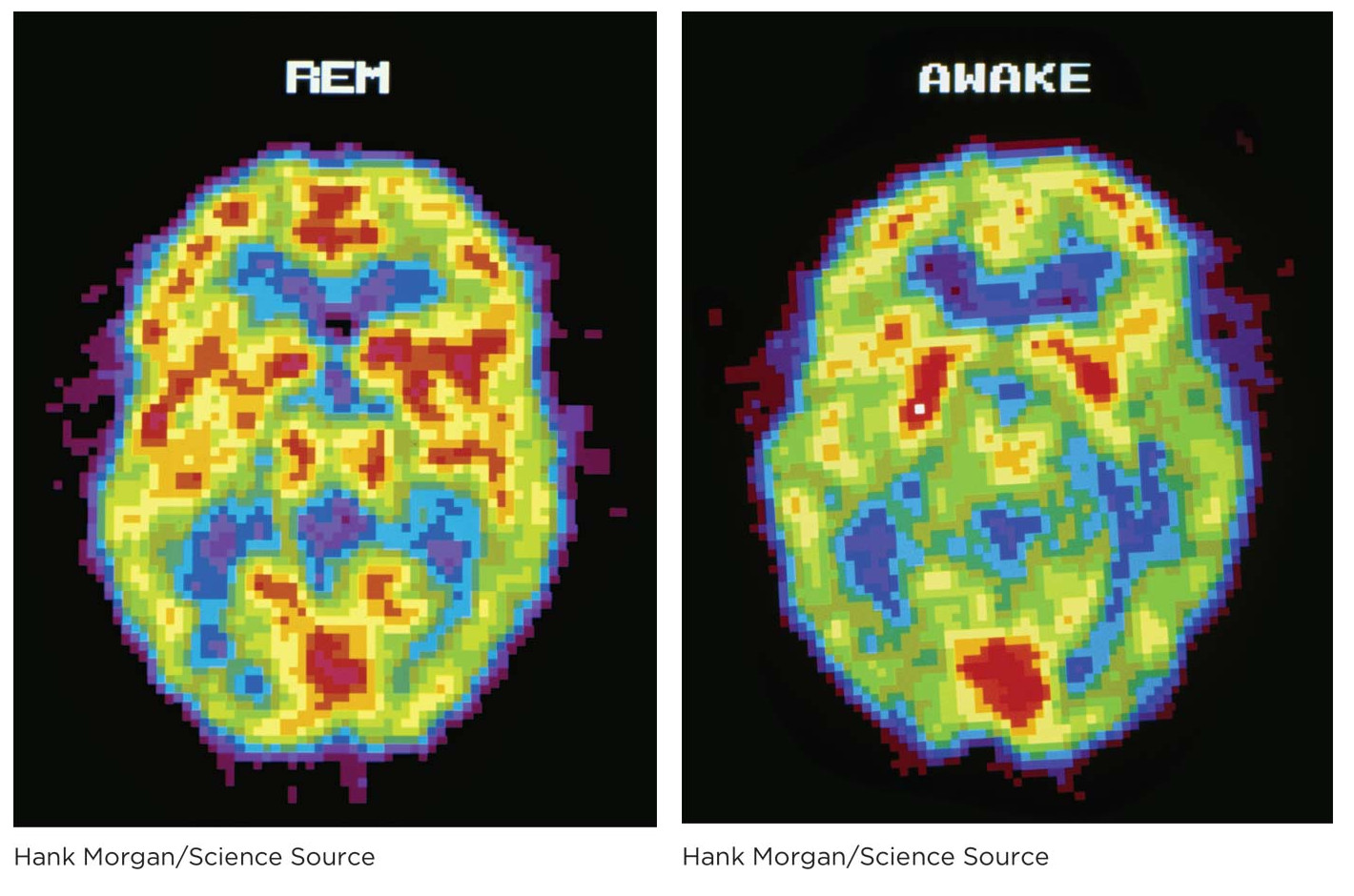

PET scans reveal the high levels of brain activity during REM sleep (left) and wakefulness (right). During REM, the brain is abuzz with excitement. (This is especially true of the sensory areas.) According to the activation–

Most dreams feature ordinary, everyday scenarios like driving a car or sitting in class. The content of dreams is repetitive and in line with what we think about when we are awake, and includes similar ideas about relationships, bad luck, people, and negative feelings. In fact, the content of dreams is relatively consistent across cultures. Dreams are more likely to include sad events than happy ones and, contrary to popular assumption, less than 12% of dream time is devoted to sexual activity (Yu & Fu, 2011). If you’re one of those people who believe they don’t dream, you are probably wrong. Most individuals who insist they don’t dream simply fail to remember their dreams. If awakened during a dream, one is more likely to recall it at that moment than if asked to remember it at lunchtime. The ability to remember dreams is dependent on the length of time since the dream.

Most dreaming takes place during REM sleep and is jam-

Have you ever realized that you are in the middle of a dream? A lucid dream is one that you are aware of having, and research suggests that about half of us have had one (Gackenbach & LaBerge, 1988). There are two parts to a lucid dream: the dream itself and the awareness that you are dreaming. Some suggest lucid dreaming is actually a way to direct the content of dreams (Gavie & Revonsuo, 2010), but this is a controversial claim because there is no way to confirm people’s subjective reports; dreams cannot be experienced by an outsider.

Fantastical, funny, or frightening, dreams represent a distinct state of consciousness, and consciousness is a fluid, ever-

show what you know

Question 1

1. Freud believed dreams have two levels. The __________________ refers to the apparent meaning of the dream, whereas the __________________ refers to its hidden meaning.

manifest content; latent content

Question 2

2. According to the __________________ , dreams have no meaning whatsoever. Instead, the brain is responding to random neural activity as if it has meaning.

psychoanalytic perspective

neurocognitive theory

activation–

synthesis model evolutionary perspective

c. activation–

Question 3

3. What occurs in the brain when you dream?

EEG and PET scan technologies can demonstrate neural activity while we sleep. During REM sleep, the motor areas of the brain are inhibited, but a great deal of neural activity is occurring in the sensory areas of the brain. The activation–

Question 4

4. Your 6-

until children are around 13 to 15 years old, their reported dreams are less vivid.

dream content is not the same across cultures.

children younger than 13 can report very complicated story lines from their dreams.

dream content is the same for people, regardless of age.

a. until children are around 13 to 15 years old, their reported dreams are less vivid.