5.1 An Introduction to Learning

Ivonne Mosquera-

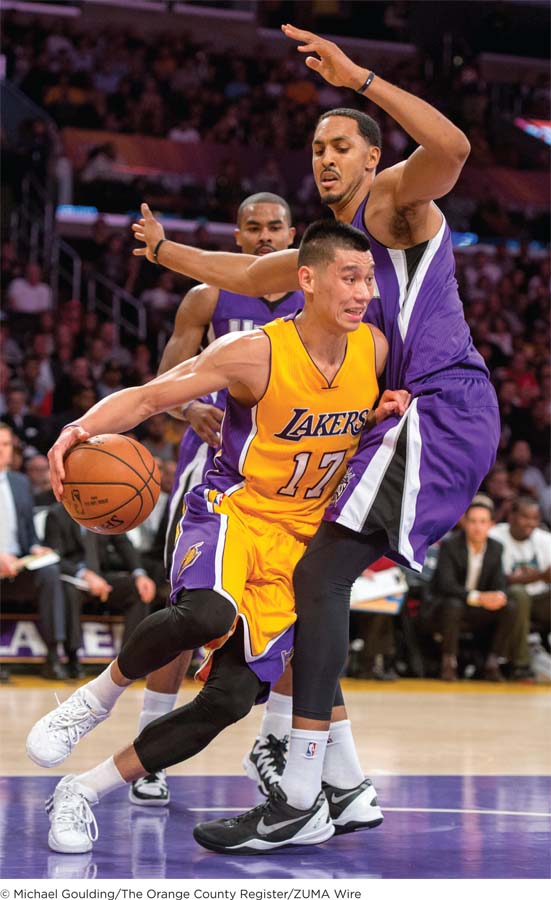

Playing for the Los Angeles Lakers in the 2014/2015 NBA season, Jeremy Lin races past Ryan Hollins of the Sacramento Kings. Jeremy’s basketball accomplishments are the result of talent, motivation, and extensive learning.

ATHLETES IN THE MAKING Palo Alto, California: It was the spring of 1999, and Ivonne Mosquera was about to graduate from Stanford University with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics. Math majors typically spend a lot of time manipulating numbers on paper, graphing functions, and trying to understand spatial relationships—

Blindness never stopped Ivonne from doing much of anything. Growing up in New York City, she used to ride her bicycle across the George Washington Bridge as her father ran alongside. She went to school with sighted kids, climbed trees in the park, and studied ballet, tap, and jazz dance (Boccella, 2012, May 6; iminmotion.net, n.d., para. 3). She tried downhill skiing, hiking, and rock climbing. Now Ivonne was graduating from college with a degree in one of the most rigorous academic disciplines, a great accomplishment indeed. Yet there were bigger things to come for Ivonne. In the next decade, she would become a world-

Meanwhile, just a few miles from the Stanford campus, a 10-

At first glance, Ivonne Mosquera (now Ivonne Mosquera-

Note: Quotations attributed to Ivonne Mosquera-

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LO 1 Define learning.

LO 2 Explain what Pavlov’s studies teach us about classical conditioning.

LO 3 Identify the differences between the US, UR, CS, and CR.

LO 4 Recognize and give examples of stimulus generalization and stimulus discrimination.

LO 5 Summarize how classical conditioning is dependent on the biology of the organism.

LO 6 Describe the Little Albert study and explain how fear can be learned.

LO 7 Describe Thorndike’s law of effect.

LO 8 Explain shaping and the method of successive approximations.

LO 9 Identify the differences between positive and negative reinforcement.

LO 10 Distinguish between primary and secondary reinforcers.

LO 11 Describe continuous reinforcement and partial reinforcement.

LO 12 Name the schedules of reinforcement and give examples of each.

LO 13 Explain how punishment differs from negative reinforcement.

LO 14 Summarize what Bandura’s classic Bobo doll study teaches us about learning.

LO 15 Describe latent learning and explain how cognition is involved in learning.

What Is Learning?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described circumstances in which learning influences the brain and vice versa. For example, dopamine plays an important role in learning through reinforcement, attention, and regulating body movements. Neurogenesis (the generation of new neurons) is also thought to be associated with learning.

In Chapter 3, we discussed sensory adaptation, which is the tendency to become less aware of constant stimuli. Becoming habituated to sensory input keeps us alert to changes in the environment.

LO 1 Define learning.

learning A relatively enduring change in behavior or thinking that results from experiences.

Ivonne and her guide prepare for the 2012 Paratriathlon World Championships in Auckland, New Zealand. Ivonne is about to begin the swim portion of the triathlon, which takes place in the frigid ocean waters along Queens Wharf. She wears a wetsuit to keep her warm. The red string just below her knee is the tether that keeps her connected to the guide.

Psychologists define learning as a relatively enduring change in behavior or thinking that results from our experiences. Studies suggest that learning can begin before we are even born—

Army Specialist Antonio Ingram gets a kiss from Emma, one of the therapy dogs that works with soldiers at Fort Hood, Texas (Flaherty, 2011, October 29). Therapy animals like Emma help ease the stress of wounded veterans, abused children, cancer patients, and others suffering from psychological distress (American Humane Association, 2013). The dogs are trained using the principles of learning.

habituation (hah-

stimulus An event or occurrence that generally leads to a response.

The ability to learn is not unique to humans. Trout can learn to press a pendulum to get food (Yue, Duncan, & Moccia, 2008); orangutans can pick up whistling (Wich et al., 2009); and even honeybees can be trained to differentiate among photos of human faces (Dyer, Neumeyer, & Chittka, 2005). One of the most basic forms of learning occurs during the process of habituation (hah-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described the theme of nature and nurture, which examines the relative weight of heredity and environment. Some scientists who initially studied the biological and innate aspects (nature) of animals shifted their focus and began to study how experiences and learning (nurture) influenced these animals.

In Chapter 1, we discussed Institutional Review Boards, which must approve all research with human participants and animal subjects to ensure safe and humane procedures.

Researchers have studied learning using a variety of animals. The history of psychology is full of stories about scientists who began studying animal biology but then switched their focus to animal behavior as unexpected events unfolded in the laboratory. These scientists were often excited to find the connections between biology and experience that became evident as they explored the principles of learning.

Animals are often excellent models for studying and understanding human behavior. Conducting animal research sidesteps many of the ethical dilemmas that arise with human research. It’s generally considered okay to keep rats, cats, and birds in cages to ensure control over experimental variables (as long as they are otherwise treated humanely), but locking up people in laboratories would obviously be unacceptable.

This chapter focuses on three major types of learning: classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning. As you make your way through these pages, you will begin to realize that learning is very much about creating associations. Through classical conditioning, we associate two different stimuli: for example, the sound of a bell and the arrival of food. In operant conditioning, we make connections between our behaviors and their consequences: for example, through rewards and punishments. With observational learning, we learn by watching and imitating other people, establishing a closer link between our behavior and the behavior of others.

Learning can occur in predictable or unexpected ways. It allows us to grow and change, and it is a key to achieving goals. Now let’s see how learning has shaped the lives of Ivonne Mosquera-

AN OMINOUS SMELL Ivonne is on her way to swim practice. As she walks through the locker room and approaches the pool entrance, she catches a whiff of chlorine. Immediately, her shoulders tense and her heart rate jumps. The smell of chlorine gives Ivonne the jitters, not because there is something inherent about the chemical that causes a physical reaction, but because it is associated with something she dreads: swimming.

AN OMINOUS SMELL Ivonne is on her way to swim practice. As she walks through the locker room and approaches the pool entrance, she catches a whiff of chlorine. Immediately, her shoulders tense and her heart rate jumps. The smell of chlorine gives Ivonne the jitters, not because there is something inherent about the chemical that causes a physical reaction, but because it is associated with something she dreads: swimming.

“I’ve never been a strong swimmer,” Ivonne says. “I just survive in water.” Submerging her ears in water, which is necessary when she swims the freestyle stroke in triathlons, makes Ivonne feel disoriented. “I can’t hear what’s around me,” she explains. “There aren’t sounds or echoes for me to follow.”

Imagine navigating a mile in the frigid ocean bordering Canada in the Vancouver Triathlon, or plowing through choppy waves (not to mention dodging pieces of trash) in the Hudson River in New York City’s triathlon. Now imagine doing all of that swimming in the darkness. It’s no surprise that Ivonne feels a little apprehensive about being in the water.

To understand why the smell of chlorine seems to evoke such a strong physiological response for Ivonne, we need to travel back in time and into the lab of a young Russian scientist: Ivan Pavlov.

show what you know

Question 1

1. Learning is a relatively enduring change in __________ that results from our __________.

behavior or thinking; experiences

Question 2

2. Learning is often described as the creation of __________, for example, between two stimuli or between a behavior and its consequences.

habituation

ethical dilemmas

associations

unexpected events

c. associations