5.2 Classical Conditioning

LO 2 Explain what Pavlov’s studies teach us about classical conditioning.

The son of a village priest, Ivan Pavlov (1849–

CONNECTIONS

A dog naturally begins to salivate when exposed to the smell of food, even before tasting it. This is an involuntary response of the autonomic nervous system, which we explored in Chapter 2. Dogs do not normally salivate at the sound of footsteps. Here, we see this response is a learned behavior, as the dog salivates without tasting or smelling food.

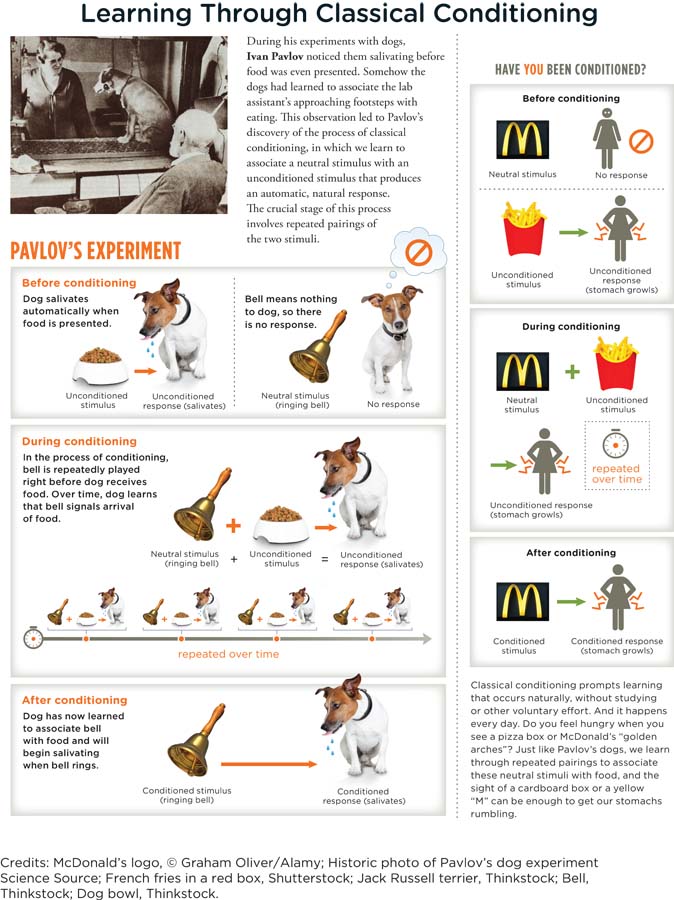

Pavlov spent the 1890s studying the digestive system of dogs at Russia’s Institute of Experimental Medicine (Watson, 1968). One of his early experiments involved measuring how much dogs salivate in response to food. Initially, the dogs salivated as expected, but as the experiment progressed, they began salivating to other stimuli as well. After repeated trials with an assistant giving a dog its food and then measuring the dog’s saliva output, Pavlov noticed that instead of salivating the moment it received food, the dog began to salivate at the mere sight or sound of the lab assistant arriving to feed it. The assistant’s footsteps, for example, seemed to act like a trigger (the stimulus) for the dog to start salivating (the response). Pavlov had discovered how associations develop through the process of learning, which he referred to as conditioning. The dog was associating the sound of footsteps with the arrival of food; it had been conditioned to associate certain sights and sounds with eating. Intrigued by his discovery, Pavlov decided to shift the focus of his research to investigate the dogs’ salivation (which he termed “psychic secretions”) in these types of scenarios (Fancher & Rutherford, 2012, p. 248; Watson, 1968).

Pavlov’s Basic Research Plan

Pavlov conditioned his dogs to salivate in response to auditory stimuli, such as bells and ticking metronomes. A metronome is a device that musicians often use to maintain tempo. This “old-

Pavlov followed up on his initial observations with numerous studies in the early 1900s, examining the link between stimulus (for example, the sound of human footsteps) and response (the dog’s salivation). The type of behavior Pavlov was studying (salivating) is not voluntary, but involuntary or reflexive (Pavlov, 1906). The connection between food and salivating is innate and universal, whereas the link between the sound of footsteps and salivating is learned. Learning has occurred whenever a new, nonuniversal link between stimulus (footsteps) and response (salivation) is established.

Many of Pavlov’s studies had the same basic format (Infographic 5.1). Prior to the experiment, the dog had a tube surgically inserted into its cheek to allow for the precise collection of saliva. When the dog salivated, instead of the secretions being swallowed, they were emptied from that tube into a measuring device so Pavlov could determine exactly how much the dog was producing.

INFOGRAPHIC 5.1

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the importance of control in the experimental method. In this case, if the sound of footsteps was the stimulus, then Pavlov would need to control the number of steps taken, the type of shoes worn, and so on, to ensure the stimulus was identical for each trial. Otherwise, he would be introducing extraneous variables, which are characteristics that interfere with the outcome of research, making it difficult to determine what exactly was causing the dog to salivate.

Because Pavlov was interested in exploring the link between a stimulus and the dog’s response, he had to pick a stimulus that was more controlled than the sound of someone walking into a room. Pavlov used a variety of stimuli, such as sounds produced by metronomes, buzzers, and bells, which under normal circumstances have nothing to do with food. In other words, they are neutral stimuli in relation to feeding and responses to food.

On numerous occasions during an experimental trial, Pavlov and his assistants presented a dog with a chosen sound—

Time for Some Terms

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed operational definitions, which are the precise ways in which characteristics of interest are defined and measured. Although earlier we described the research in everyday language, here we provide operational definitions for the procedures of the study.

neutral stimulus (NS) A stimulus that does not cause a relevant automatic or reflexive response.

LO 3 Identify the differences between the US, UR, CS, and CR.

classical conditioning Learning process in which two stimuli become associated with each other; when an originally neutral stimulus is conditioned to elicit an involuntary response.

Now that you know Pavlov’s basic research procedure, it is important to learn the specific terminology psychologists use to describe what is happening (Infographic 5.1). Before the experiment began, the tone was a neutral stimulus (NS)—something in the environment that does not normally cause a relevant automatic or reflexive response. In the current example, salivation is the automatic response associated with food; dogs do not normally respond to the tone of a bell by salivating. But through experience, the dogs learned to link this neutral stimulus (the tone) with another stimulus (food) that prompts an automatic, unlearned response (salivation). This type of learning is classical conditioning, and it occurs when an originally neutral stimulus is conditioned to elicit or induce an involuntary response, such as salivation, eye blinks, and other types of reflex reactions.

Synonyms

classical conditioning Pavlovian conditioning

unconditioned stimulus (US) A stimulus that automatically triggers an involuntary response without any learning needed.

unconditioned response (UR) A reflexive, involuntary response to an unconditioned stimulus.

conditioned stimulus (CS) A previously neutral stimulus that an organism learns to associate with an unconditioned stimulus.

conditioned response (CR) A learned response to a conditioned stimulus.

US, UR, CS, AND CR At the start of a trial, before the dogs were conditioned or had learned anything about the neutral stimulus, they salivated when they smelled or were given food. The food is called an unconditioned stimulus (US) because it triggers an automatic response without any learning needed. Salivation by the dogs when exposed to food is an unconditioned response (UR) because it doesn’t require any conditioning (learning); the dog just does it involuntarily. The salivation (the UR) is an automatic response elicited by the smell or taste of food (the US). After conditioning has occurred, the dog responds to the tone of the bell almost as if it were food. The tone, previously a neutral stimulus, has now become a conditioned stimulus (CS) because it triggers the dog’s salivation. When the salivation occurs in response to the tone, it is called a conditioned response (CR); the salivation is a learned response.

acquisition The initial learning phase in both classical and operant conditioning.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described the scientific method and how it depends on objective observations. An objective approach requires scientists to make their observations without the influence of personal opinion or preconceived notions. We are all prone to biases, but the scientific method helps minimize their effects. Pavlov was among the first to insist that behavior must be studied objectively.

THE ACQUISITION PHASE The pairings of the neutral stimulus (the tone) with the US (the meat powder) occur during the acquisition or initial learning phase. Some points to remember:

The meat powder is always a US (the dog never has to learn how to respond to it).

The dog’s salivating is initially a UR to the meat powder, but eventually becomes a CR as it occurs in response to the tone (without the sight or smell of meat powder).

The US is always different from the CS; the US automatically triggers the response, but with the CS, the response has been learned by the organism.

Pavlov’s work paved the way for a new generation of psychologists who considered behavior to be a topic of objective, scientific study. Like many who would follow, he believed that scientists should focus only on observable behaviors; his work transformed our understanding of learning and our approach to psychological research.

Nuts and Bolts of Classical Conditioning

We have learned about Pavlov’s dogs and their demonstration of classical conditioning. We have defined the terminology associated with that process. Now it’s time to take our learning (about learning) to the next level and examine some of the principles that guide the process.

LO 4 Recognize and give examples of stimulus generalization and stimulus discrimination.

stimulus generalization The tendency for stimuli similar to the conditioned stimulus to elicit the conditioned response.

STIMULUS GENERALIZATION What would happen if a dog in one of Pavlov’s experiments heard a slightly higher-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we introduced the concept of a difference threshold, which is the minimum difference between two stimuli that is noticed 50% of the time. Here, we see that difference thresholds can play a role in stimulus discrimination tasks. The conditioned stimulus and the comparison stimuli must be sufficiently different to be distinguished; that is, their difference is greater than the difference threshold.

stimulus discrimination The ability to differentiate between a conditioned stimulus and other stimuli sufficiently different from it.

STIMULUS DISCRIMINATION Next let’s see what would happen if you presented Pavlov’s dogs with two stimuli that differed significantly. Believe it or not, the dogs would be able to tell them apart. If you presented the meat powder with a high-

extinction In classical conditioning, the process by which the CR decreases after repeated exposure to the CS in the absence of the US; in operant conditioning, the disappearance of a learned behavior through the removal of its reinforcer.

EXTINCTION Once the dogs in a classical conditioning experiment associate the tone of a bell with meat powder, can they ever listen to the sound without salivating? The answer is yes—

spontaneous recovery The reappearance of a conditioned response following its extinction.

SPONTANEOUS RECOVERY But take note: Even with extinction, the connection is not necessarily gone forever. For example, Pavlov (1927/1960) used classical conditioning with a dog to form an association between the tone of a bell and meat powder. Once the tone was associated with the salivation, he stopped presenting the meat powder, and the association was extinguished (the dog didn’t salivate in response to the tone). Two hours following this extinction, Pavlov presented the tone again and the dog salivated. This reappearance of the conditioned response following its extinction is called spontaneous recovery. With the presentation of a CS after a period of rest, the CR reappears. The dog had not “forgotten” the association when the pairing was extinguished. Rather, the CR was “suppressed” when the dog was not being exposed to the US. Two hours later when the bell (the CS) sounded in the absence of food (the US), the association reemerged; the link between the tone and the food had been simmering beneath the surface. Let’s return to that refreshing glass of lemonade—

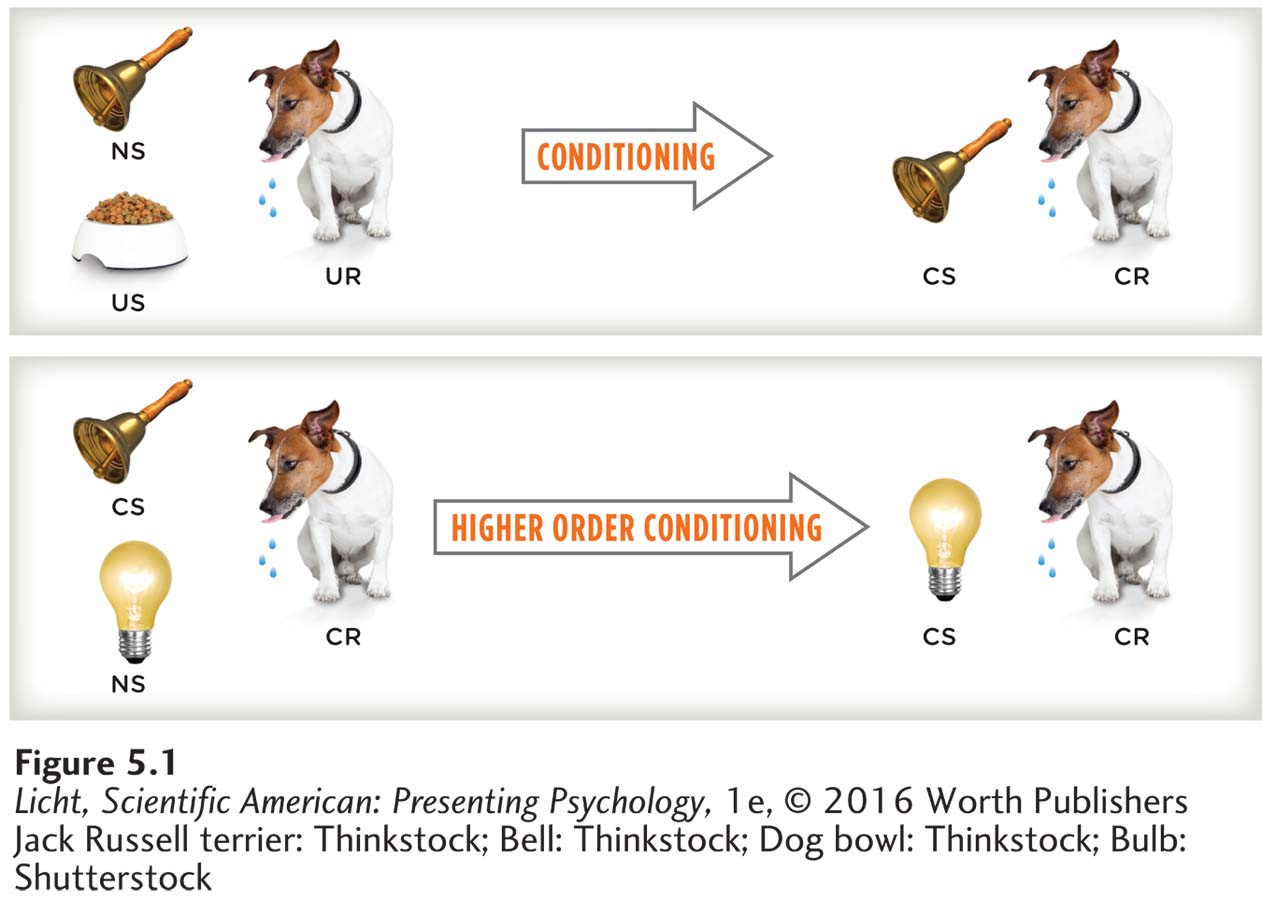

higher order conditioning With repeated pairings of a conditioned stimulus and a neutral stimulus, the second neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus as well.

HIGHER ORDER CONDITIONING After the acquisition phase, it is possible to add another layer to the conditioning process. Suppose the tone of the bell has become a CS for the dog, such that every time it sounds, the dog has learned to salivate. Once this conditioning is established, the researcher can add a new neutral stimulus, such as a light flashing, every time the dog hears the sound of the tone. After pairing the sound and the light together (without the meat powder anywhere in sight or smell), the light will become associated with the sound and the dog will begin to salivate in response to seeing the light alone. This is called higher order conditioning (Figure 5.1). With repeated pairings of the CS (the tone) and a new neutral stimulus (the light), the second neutral stimulus becomes a CS as well. When all is said and done, both stimuli (the sound and the light) have gone from being neutral stimuli to conditioned stimuli, and either of them can elicit the CR (salivation). But in higher order conditioning, the second neutral stimulus is paired with a CS instead of being paired with the original US (Pavlov, 1927/1960). In our example, the light is associated with the sound, not with the food directly.

Once an association has been made through classical conditioning, the conditioned stimulus can be used to acquire new learned associations. Here, when a conditioned stimulus (such as a bell that now triggers salivation) is repeatedly paired with a neutral stimulus (NS) such as a flashing light, the dog will learn to salivate in response to the light—

Humans also learn to salivate when presented with stimuli that signal the delivery of food. Perhaps your nightly routine includes making dinner during television commercial breaks, and your mouth begins to water as you prepare your food. Initially, the commercials are neutral stimuli, but maybe you have gotten into the habit of preparing food only during those breaks. Making your food (CS) causes you to salivate (CR), and because dinner preparation always happens during commercials, those commercials will eventually have the power to make you salivate (CR) as well, even in the absence of food. Here we have an example of higher order conditioning, wherein additional stimuli elicit the CR.

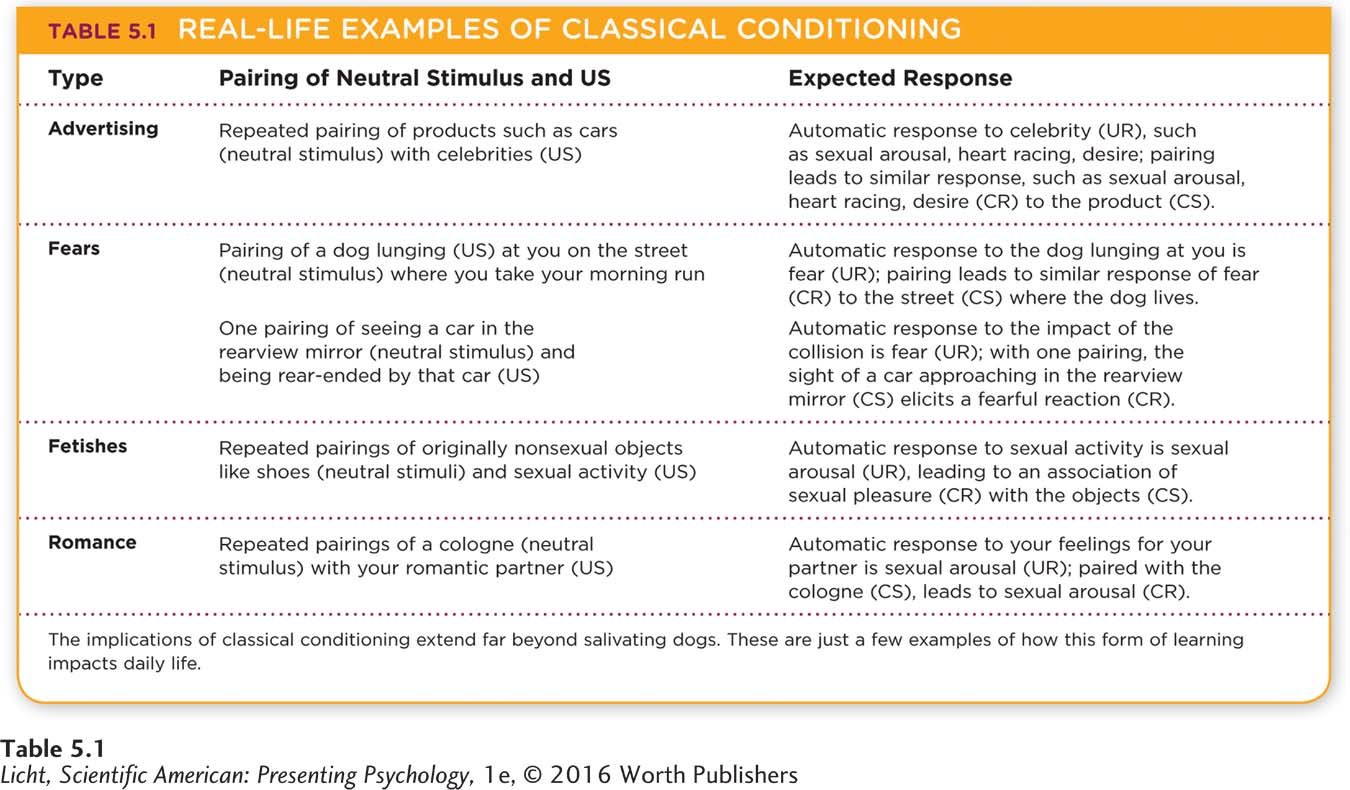

Classical conditioning is not limited to examples of salivation. It affects you in ways you may not even realize. Think of what happens to your heart rate, for example, when you walk into a room where you have had a bad experience. See Table 5.1 below for some additional real-

From Dogs to Triathletes: Extending Pavlov

Although Ivonne has now completed over 25 triathlons, she is not particularly comfortable with the swimming portion of the event. Just smelling chlorinated pool water makes her heart beat faster and her muscles tense—

Getting in the water has always made Ivonne uneasy, making her muscles tighten and her heart pump faster. She experiences this physiological fear response (the UR) because she feels disoriented when her ears, which she uses for navigation, are submerged. Her disorientation would be considered an unconditioned stimulus (US). During the acquisition phase, Ivonne began to associate the smell of chlorine (a neutral stimulus) with the disorientation she feels (US) while swimming. Every time she went to the pool, the odor of chlorine was in the air. With repeated pairings of the chlorine smell and the disoriented feeling, the neutral stimulus became linked with the US. Now, simply smelling chlorine evokes the same physiological response she has when she feels disoriented in the water. The chlorine odor went from being a neutral stimulus to a conditioned stimulus that elicits the now conditioned response of her fear reaction.

Now let’s explore a more hypothetical situation. If Ivonne were to smell dishes rinsed in a bleach solution or chlorine-

Stimulus discrimination also applies to Ivonne’s example. A gym locker room is filled with all sorts of odors: hair spray, shampoo, and sweaty socks, just to mention a few. Of all the scents in the locker room, chlorine is the only one that gets her heart racing. The fact that Ivonne can single out this odor even when bombarded with other smells and sounds demonstrates her ability to differentiate the CS from other stimuli.

It would be nice for Ivonne if the smell of chlorine no longer made her heart race. There are two ways that she could get rid of this classically conditioned response. First, she could stop swimming for a very long time, and the association might fade away through extinction. But quite often avoidance does not extinguish a classically conditioned response, as the possibility of spontaneous recovery always exists. (Recovery in this sense means recovering the conditioned response of fear, not the more familiar sense of “getting better.”) And clearly, this approach is not practical for Ivonne.

The second option is to pair a new response with the US or the CS. For example, Ivonne could practice relaxation skills and positive race visualization that includes a successful completion of the swim, until swimming itself no longer triggers the anxiety. With this accomplished, the chlorine would cease to stir up anxiety as well. Or Ivonne could gradually expose herself to the smell of chlorine while maintaining a state of relaxation, thus preventing the learned anxiety and fear response. In Chapter 13, we present some techniques therapists use to help individuals struggling with anxiety and fear.

Yuck: Conditioned Taste Aversion

LO 5 Summarize how classical conditioning is dependent on the biology of the organism.

conditioned taste aversion A form of classical conditioning that occurs when an organism learns to associate the taste of a particular food or drink with illness.

Have you ever experienced food poisoning? After falling ill from something you ate, whether it was sushi, uncooked chicken, or tainted peanut butter, you probably steered clear of that particular food for a while. This is an example of conditioned taste aversion, a powerful form of classical conditioning that occurs when an organism learns to associate the taste of a particular food or drink with illness. Imagine a grizzly bear that avoids poisonous berries after vomiting all day from eating them. Often it only takes a single pairing between a food and a bad feeling—

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced the evolutionary perspective, which suggests that adaptive behaviors and traits are shaped by natural selection. Here, the evolutionary perspective helps clarify why some types of learning are so powerful. In the case of conditioned taste aversion, species gain an evolutionary advantage through quick and efficient learning about poisonous foods.

adaptive value The degree to which a trait or behavior helps an organism survive.

Avoiding foods that induce sickness has adaptive value, meaning it helps organisms survive, upping the odds they will reproduce and pass their genes along to the next generation. According to the evolutionary perspective, humans and other animals have a powerful drive to ensure that they and their offspring reach reproductive age, so it’s critical to steer clear of tastes that have been associated with illness.

How might conditioned taste aversion play out in your life? Suppose you eat a hot dog a few hours before coming down with a stomach virus that’s coincidentally spreading throughout your college. The hot dog isn’t responsible for your illness—

RATS WITH BELLYACHES American psychologist John Garcia and his colleagues provided a demonstration of taste aversion in their well-

biological preparedness The tendency for animals to be predisposed or inclined to form associations.

The rats in Garcia’s studies seemed naturally inclined to link their “internal malaise” (sick feeling) to tastes and smells and less likely to associate the nausea with other types of stimuli related to their hearing or vision, such as noises or things they saw (Garcia et al., 1966). This is clearly an adaptive trait, because nausea often results from ingesting food that is poisonous or spoiled. In order to survive, an animal must be able to recognize and shun the tastes of dangerous substances. Garcia’s research highlights the importance of biological preparedness, the predisposition or inclination of animals (and people) to form certain kinds of associations through classical conditioning. Conditioned taste aversion is a powerful form of learning; would you believe it can be used to save endangered species?

didn’t SEE that coming

Rescuing Animals with Classical Conditioning

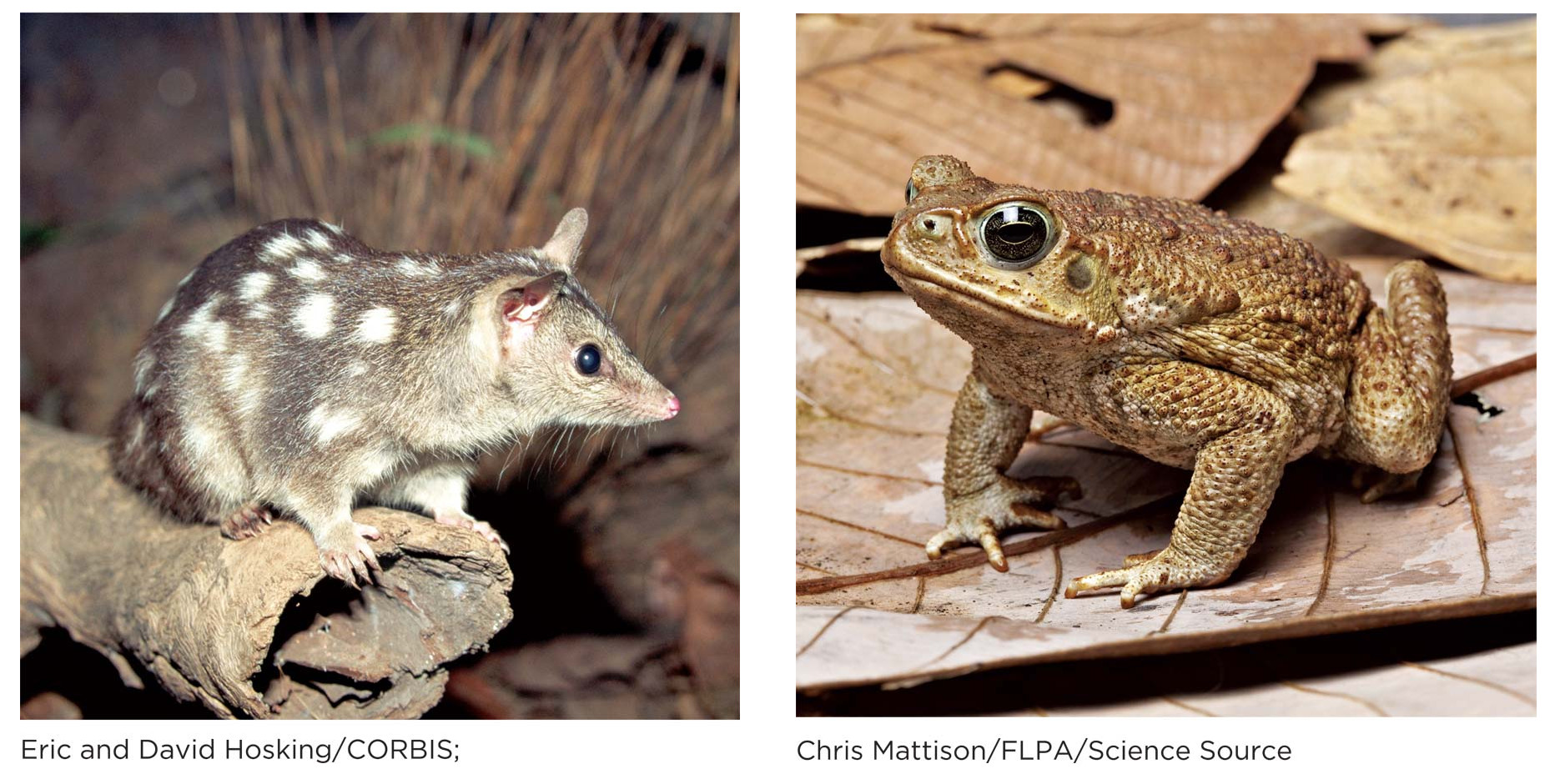

Using your newfound knowledge of conditioned taste aversion, imagine how you might solve the following problem: An animal is in trouble in Australia. The northern quoll, a meat-

Using your newfound knowledge of conditioned taste aversion, imagine how you might solve the following problem: An animal is in trouble in Australia. The northern quoll, a meat-

EATING A POISONOUS TOAD CAN TAKE A QUOLL!

Remember that conditioned taste aversion occurs when an organism rejects a food or drink after consuming it and becoming very sick. To condition the quolls to stop eating the toxic toads, you must teach them to associate the little amphibians with nausea. You could do this by feeding them non-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced two types of research. Basic research is focused on gathering knowledge for the sake of knowledge. Applied research focuses on changing behaviors and outcomes, often leading to real-

Australia’s northern quoll (left) is threatened by the introduction of an invasive species known as the cane toad (right). The quolls eat the toads, which carry a lethal dose of poison, but they can learn to avoid this toxic prey through conditioned taste aversion (O’Donnell et al., 2010).

Similar approaches are being tried across the world. For example, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is using taste aversion to discourage endangered Mexican wolves from feasting on livestock in New Mexico and Arizona (Bryan, 2012, January 28). As you see, lessons learned by psychologists working in a lab can have far-

Little Albert and Conditioned Emotional Response

LO 6 Describe the Little Albert study and explain how fear can be learned.

conditioned emotional response An emotional reaction acquired through classical conditioning; process by which an emotional reaction becomes associated with a previously neutral stimulus.

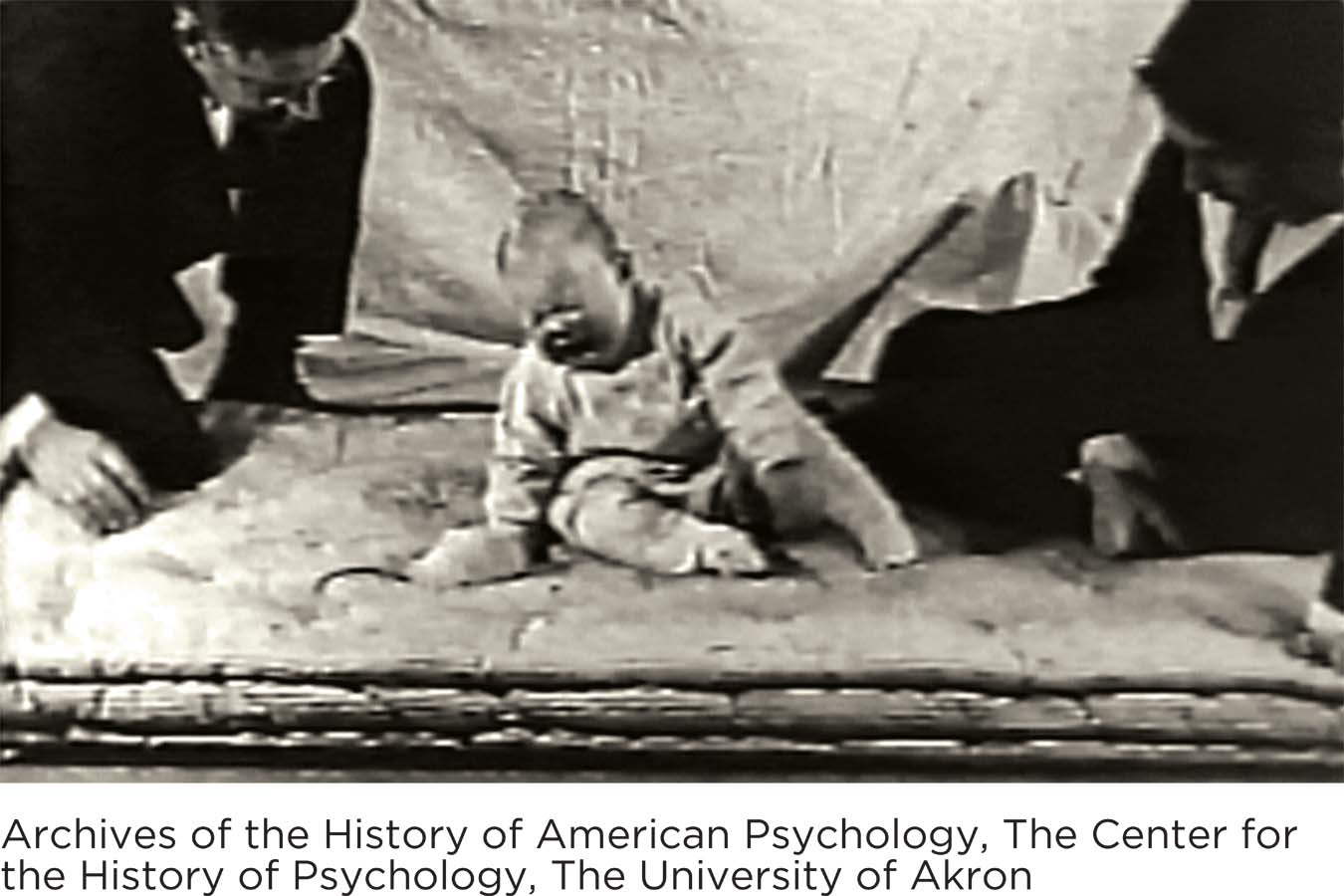

“Little Albert” was an 11-

So far, we have focused chiefly on the classical conditioning of physical responses—

The classic case study of “Little Albert,” conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner, provides a famous illustration of a conditioned emotional response (Watson & Rayner, 1920). Little Albert was an 11-

Nobody knows exactly what happened to Little Albert after he participated in Watson and Rayner’s research. Some psychologists believe Little Albert’s true identity is still unknown (Powell, 2010; Reese, 2010). Others have proposed Little Albert was Douglas Merritte, who at age 6 died of hydrocephalus (Beck & Irons, 2011; Beck, Levinson, & Irons, 2009). More recently, researchers have proposed that Little Albert was William Albert Barger (later known as William Albert Martin), who lived until 2007 and reportedly did not like animals (Powell, Digdon, Harris, & Smithson, 2014). Did Barger’s distaste for animals stem from his participation in Watson and Rayner’s experiment, or was it the result of seeing a childhood pet killed in an accident? Researchers cannot be sure, and we may never know the true identity of Little Albert or the long-

The Little Albert study would never happen today; at least, we hope it wouldn’t. Contemporary psychologists conduct research according to stringent ethical guidelines, and instilling terror in a baby would not be considered acceptable (and would not be allowed at research institutions). However, it is not too far out to imagine a similar scenario playing out in real life. Picture a toddler who is about to reach for a rat on the kitchen floor. A parent sees this happening and shouts “NO!” It would not take many pairings of the toddler reaching for the rat and the parent shouting “NO!” for the child to develop a fear of the rat. In this real-

Classical Conditioning: Do You Buy It?

Justin Bieber models underwear for Calvin Klein’s Spring 2015 ad campaign. Research suggests that advertisements may instill attitudes toward brands through classical conditioning (Grossman & Till, 1998), but how do these attitudes affect sales? Now that is a question worth researching.

Classical conditioning has applications in marketing and sales (Table 5.1). Some research suggests that advertisements can instill emotions and attitudes toward product brands through classical conditioning, and that these responses may linger as long as 3 weeks (Grossman & Till, 1998). In one study, some participants were shown pictures of pleasant scenes (such as a tropical location or a panda in a natural setting) paired with a fictitious mouthwash brand. Participants who were exposed to the mouthwash (originally a neutral stimulus) and the favorable pictures (the US) were more likely to retain a positive enduring attitude (now the CR) toward the mouthwash (which became a CS) than participants who were exposed to the entire same set of pictures paired in random order. In other words, the researchers were able to create “favorable attitudes” toward the fictitious brand of mouthwash by pairing pictures of the mouthwash with scenery that evoked positive emotions (Grossman & Till, 1998). The study did not address whether this favorable attitude leads to a purchase, however.

Do you think you are susceptible to this kind of conditioning? We would venture to say that we all are. Complete the following Try This to see if classical conditioning affects your attitudes and feelings toward everyday products.

Remember that classical conditioning is a type of learning associated with automatic (or involuntary) behaviors. You don’t “learn” to go out and buy a particular brand of mouthwash through classical conditioning. Classical conditioning can influence our attitudes toward products, but it can’t teach us voluntary behaviors. Well then, how do we learn these types of deliberate behaviors? Read on.

Marketers use classical conditioning to instill positive emotions and attitudes toward product brands. List examples of recent advertisements you have seen on television or the Internet that use this approach to get people to buy products. Which of your recent purchases may have been influenced by such ads?

try this

show what you know

Question 1

1. __________ is the learning process in which two stimuli become associated.

Classical conditioning

Question 2

2. Because of __________, animals and people are predisposed or inclined to form associations that increase their chances of survival.

biological preparedness

Question 3

3. Hamburgers were once your favorite food, but ever since you ate a burger tainted with salmonella (which causes food poisoning), you cannot smell or taste one without feeling nauseous. Which of the following is the unconditioned stimulus?

salmonella

nausea

hamburgers

the hamburger vendor

a. salmonella

Question 4

4. Watson and Rayner used classical conditioning to instill fear in Little Albert. Create a diagram of the neutral stimulus, US, UR, CS, and CR used in their experiment. In what way does Little Albert show stimulus generalization?

When Little Albert heard the loud bang, it was an unconditioned stimulus (US) that elicited fear, the unconditioned response (UR). Through conditioning, the sight of the rat became paired with the loud noise, and thus the rat went from being a neutral stimulus to a conditioned stimulus (CS). Little Albert’s fear of the rat became a conditioned response (CR). Not only did Little Albert begin to fear rats, he showed stimulus generalization when he demonstrated fear to other furry objects, including a sealskin coat and a rabbit.