5.4 Observational Learning and Cognition

Playing for the Los Angeles Lakers, Jeremy Lin charges past Jerryd Bayless of the Milwaukee Bucks. Jeremy may not be the tallest player in the NBA, but he more than makes up for that in confidence and game smarts.

Baby Jeremy poses with his father Gie-

BASKETBALL IQ Jeremy Lin is not the fastest runner or highest jumper on the planet, and he is certainly not the biggest guy in professional hoops. In the world of the NBA, where the players’ average height is about 6´7˝ and the average weight is 220 pounds, Jeremy is actually somewhat small (NBA.com, 2007, November 20; NBA.com, 2007, November 27). So what is it about this benchwarmer-

BASKETBALL IQ Jeremy Lin is not the fastest runner or highest jumper on the planet, and he is certainly not the biggest guy in professional hoops. In the world of the NBA, where the players’ average height is about 6´7˝ and the average weight is 220 pounds, Jeremy is actually somewhat small (NBA.com, 2007, November 20; NBA.com, 2007, November 27). So what is it about this benchwarmer-

The roots of Jeremy’s hoop smarts reach back to his father’s native country. Growing up in Taiwan, Gie-

Synonyms

observational learning social learning

model The individual or character whose behavior is being imitated.

observational learning Learning that occurs as a result of watching the behavior of others.

The NBA greats that Gie-

The Power of Observational Learning

Think about how observational learning impacts your own life. Speaking English, eating with utensils, and driving a car are all skills you probably picked up in part by watching and mimicking others. Do you ever use slang? Phrases like “gnarley” (cool) from the 1980s, “Wassup” (What is going on?) from the 1990s, and “peeps” (my people, or friends) from the 2000s caught on because people copy what they observe others saying and writing. Consider some of the phrases trending today that 20 years from now people won’t recognize.

Observational learning doesn’t necessarily require sight. Let’s return to Ivonne, who competes in triathlons, consisting of 1 mile of swimming, 25 miles of biking, and 6 miles of running. Ivonne performs the swimming and running sections of the triathlon attached to a guide with a tether, and the bike section on a tandem bike with the guide. To fine-

LO 14 Summarize what Bandura’s classic Bobo doll study teaches us about learning.

Ivonne (rear) and her guide, Marit Ogin, ride together in the Nickel City Buffalo Triathlon. The guide is responsible for steering, breaking, and communicating to Ivonne when it is time to shift gears or adjust body position for a turn.

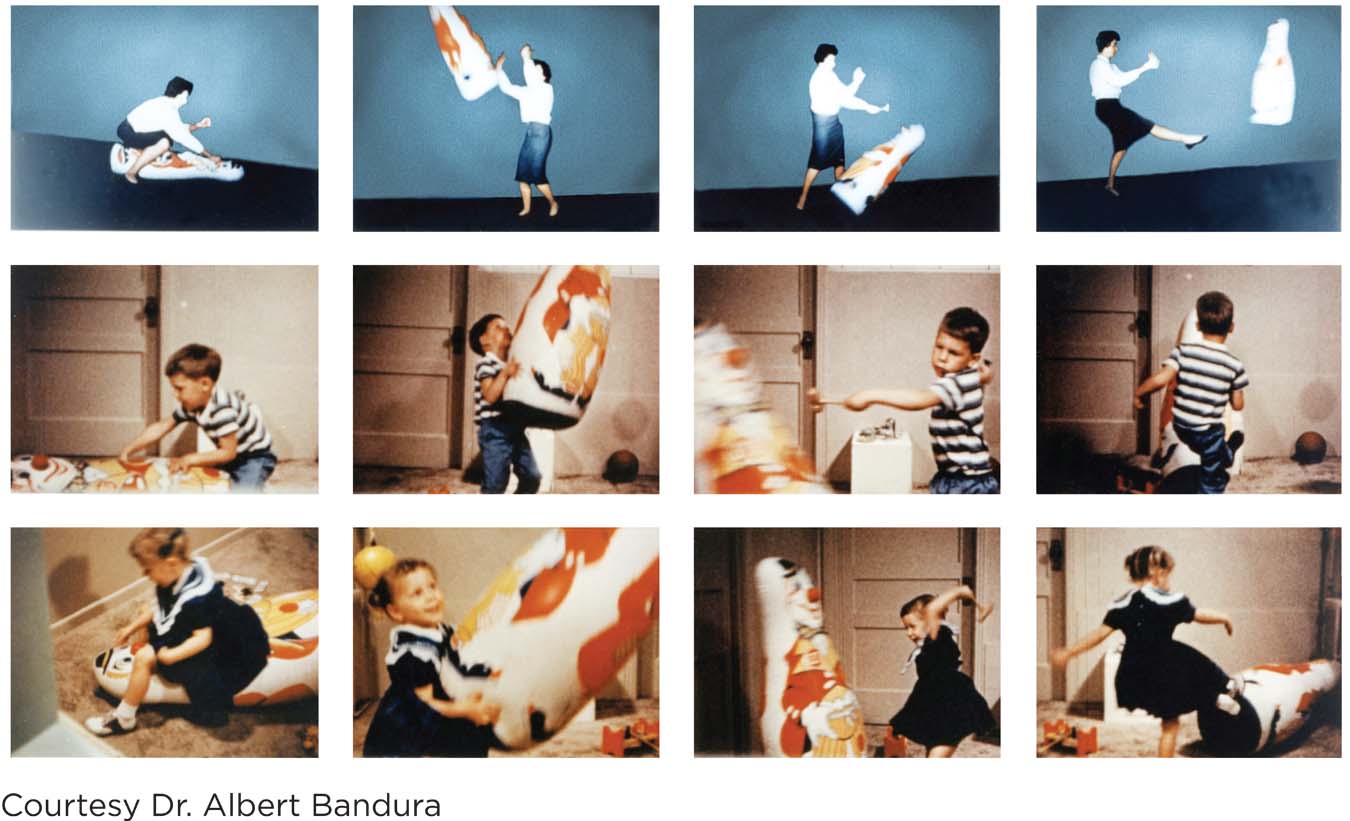

PLEASE PLAY NICELY WITH YOUR DOLL Just as observational learning can lead to positive outcomes like sharper basketball and swimming skills, it can also breed undesirable behaviors. The classic Bobo doll experiment conducted by psychologist Albert Bandura and his colleagues revealed just how fast children can adopt aggressive ways they see modeled by adults, as well as exhibit their own novel aggressive responses (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961). In one of Bandura’s studies, 76 preschool children were placed in a room alone with an adult and allowed to play with stickers and prints for making pictures. During their playtime, some of the children were paired with adults who acted aggressively toward a 5-

Preschool children in Albert Bandura’s famous Bobo doll experiment performed shocking displays of aggression after seeing violent behaviors modeled by adults. The children were more likely to copy models who were rewarded for their aggressive behavior and less likely to mimic those who were punished (Bandura, 1986).

At the end of the experiment, all the children were allowed to play with a Bobo doll themselves. Those who had observed adults attacking and shouting were much more likely to do the same. Boys were more likely than girls to mimic physical aggression, especially if they had observed it modeled by men. Boys and girls were about equally likely to imitate verbal aggression (Bandura et al., 1961).

Identify the independent variable and dependent variable in the experiment by Bandura and colleagues. What might you change if you were to replicate this experiment?

try this

Ideas for altering the study: Conducting the same study with older or younger children; exposing the children to other children (as opposed to adults) behaving aggressively; pairing children with adults of the same and different ethnicities to determine the impact of ethnic background.

VIOLENCE IN THE MEDIA Psychologists have followed up Bandura’s research with studies investigating how children are influenced by violence they see on television, the Internet, and in movies and video games. The American Academy of Pediatrics sums it up nicely: “Extensive research evidence indicates that media violence can contribute to aggressive behavior, desensitization to violence, nightmares, and fear of being harmed” (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009, p. 1495). One large study found that children who watched TV programs with violent role models, such as Starsky and Hutch (a detective series from the 1970s that included violence and suspense), were at increased risk when they became adults of physically abusing their spouses and getting into trouble with the law (Huesmann, Moise-

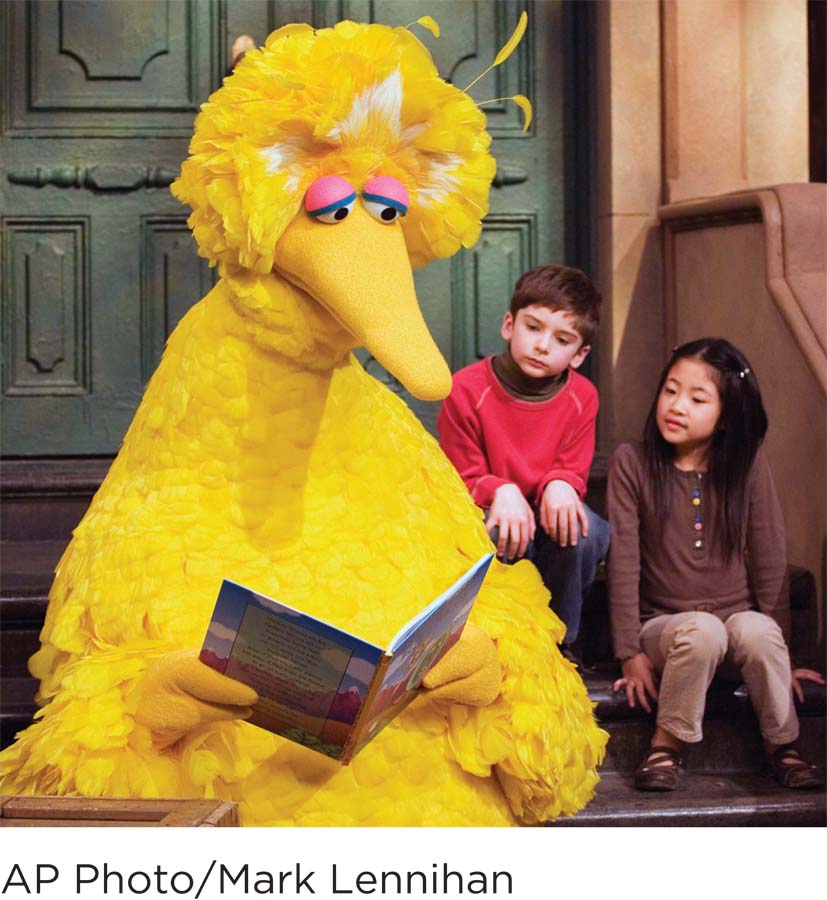

The prosocial behaviors demonstrated by Big Bird and Sesame Street friends appear to have a meaningful impact on child viewers. Children have a knack for imitating positive behaviors such as sharing and caring (Cole et al., 2008).

Critics caution, however, that an association between media portrayals and violent behaviors doesn’t mean there is a cause-

Bonnie the orangutan seems to have learned whistling by copying workers at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park in Washington, DC. Her musical skill is the result of observational learning (Stone, 2009; Wich et al., 2009).

prosocial behaviors Actions that are kind, generous, and beneficial to others.

PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR AND OBSERVATIONAL LEARNING Here’s the flip side to this issue: Children also have a gift for mimicking positive behaviors. When children watch shows similar to Sesame Street, they receive messages that encourage prosocial behaviors, meaning these programs foster kindness, generosity, and forms of behavior that benefit others.

Let’s look more closely at research on the impact of prosocial models. Using scales to measure children’s stereotypes and cultural knowledge before and after they watch TV shows, a group of researchers found evidence that shows like Sesame Street can have a positive influence (Cole, Labin, & del Rocio Galarza, 2008). Based on their review of multiple studies, these researchers made recommendations to increase prosocial behaviors. Children’s shows should have intended messages, include prosocial information about people of other cultures and religions, be relevant to children in terms of culture and environment, and be age-

Adults can also pick up prosocial messages from media. In a multipart study, researchers exposed adults to prosocial song lyrics (as opposed to neutral lyrics). The first experiment found that listening to prosocial lyrics increased the frequency of prosocial thoughts. Findings from the second experiment indicated that listening to a song with prosocial lyrics increased empathy, or the ability to understand what another person is going through. The third experiment found that listening to a song with prosocial lyrics increased helping behavior. These researchers only looked at the short-

When learning occurs through observation, often it is visible. Children watching aggression toward a Bobo doll imitate the behaviors they see, which researchers can witness and document. Not all forms of learning are so obvious.

Latent Learning

LO 15 Describe latent learning and explain how cognition is involved in learning.

Ivonne’s feet pound the streets of Boston. She is among some 20,000 runners competing in the city’s oldest annual 26.2-

cognitive map The mental representation of the layout of a physical space.

latent learning Learning that occurs without awareness and regardless of reinforcement, and is not evident until needed.

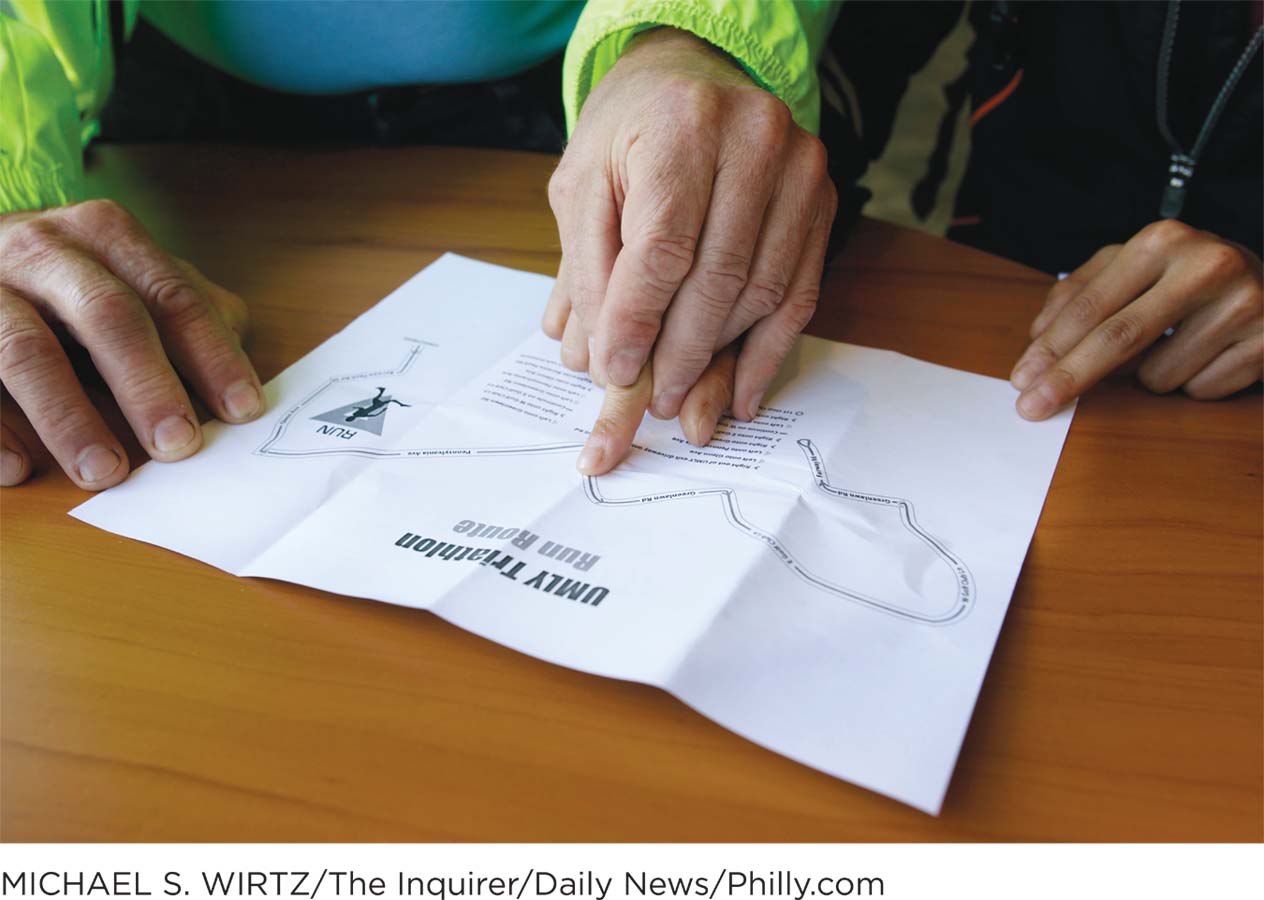

Ivonne’s husband guides her hand over the map of a racecourse. She is beginning to form a cognitive map of the route, one that will continue to crystallize as she races. While running, Ivonne’s ears collect clues about the relative positions of objects and the direction of motion—

A MAP THAT CANNOT BE SEEN Before a race, Ivonne checks online to see if there is a description of the course or studies a map with her husband or a friend in order to learn the location of important landmarks such as hills, major turns, bridges, railroad tracks, and so on. “Doing this helps me feel that I have an idea of what to expect, and when to expect it,” Ivonne says. The mental layout she creates contributes to her cognitive map, a mental representation of the physical surroundings, and it continues to come together in the race. As Ivonne runs, she hears sounds from all directions—

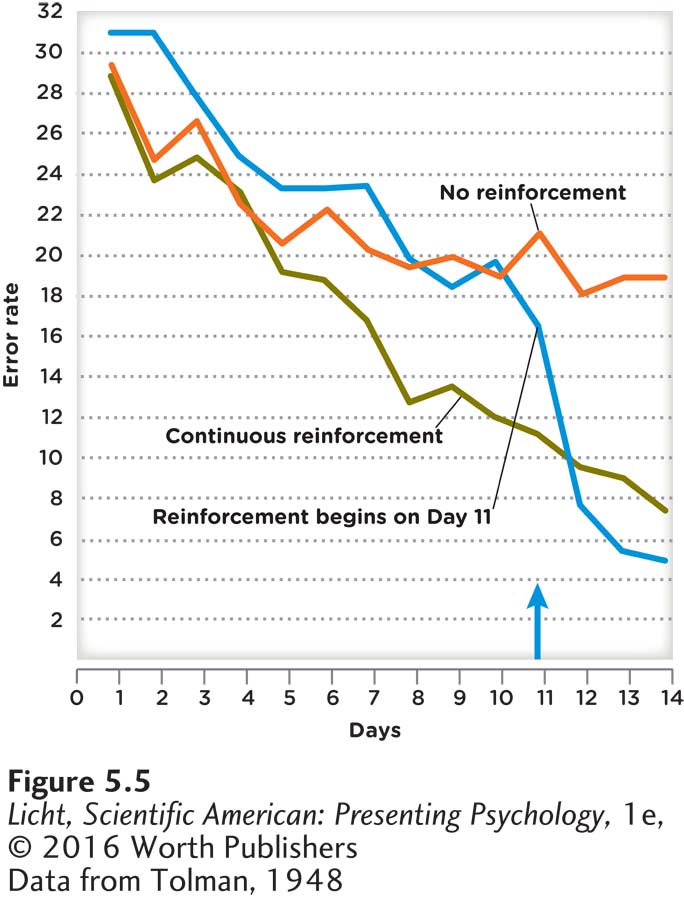

RATS THAT KNOW WHERE TO GO Edward Tolman and his colleague C. H. Honzik demonstrated latent learning in rats in their classic 1930 maze experiment (Figure 5.5, below). The researchers took three groups of rats and let them run free in mazes for several days. One group received food for reaching the goal boxes in their mazes; a second group received no reinforcement; and a third received nothing until the 11th day of the experiment, when they, too, received food for finding the goal box. As you might expect, rats getting the treats from the onset solved the mazes more quickly as the days wore on. Meanwhile, their unrewarded compatriots wandered through the twists and turns, showing only minor improvements from one day to the next. But on Day 11 when the researchers started to give treats to the third group of rats, their behavior changed markedly. After just one round of treats, the rats were scurrying through the mazes and scooping up the food as if they had been rewarded throughout the experiment (Tolman & Honzik, 1930). They had apparently been learning, even when there was no reinforcement for doing so—

In a classic experiment, groups of rats learned how to navigate a maze at remarkably different rates. Rats in a group receiving reinforcement from Day 1 (the green line on the graph) initially had the lowest rate of errors and were able to work their way through the maze more quickly than the other groups. But when a group began to receive reinforcement for the first time on Day 11, their error rate dropped immediately. This shows that the rats were learning the basic structure of the maze even when they weren’t being reinforced.

We all do this as we acquire cognitive maps of our environments. Without realizing it, we remember locations, objects, and details of our surroundings, and bring this information together in a mental layout (Lynch, 2002). Research suggests that visually impaired people forge cognitive maps without the use of visual information. Instead, they use “compensatory sensorial channels” (hearing and sense of touch, for example) to gather information about their environments (Lahav & Mioduser, 2008).

This line of research highlights the importance of cognitive processes underlying behavior and suggests that learning can occur in the absence of reinforcement. Because of the focus on cognition, this research approach conflicts with the views of Skinner and some other 20th-

Many other studies have challenged Skinner’s views. Wolfgang Köhler’s (1925) research on chimpanzees suggests that animals are capable of thinking through a problem before taking action. He designed an experiment in which chimps were presented with out-

Today, most psychologists agree that both observable, measurable behaviors and internal cognitive processes such as insight are necessary and complementary elements of learning. Environmental factors have a powerful influence on behavior, as Pavlov, Skinner, and others discovered, but every action can be traced to activity in the brain. Understanding how cognitive processes translate to behaviors remains one of the great challenges facing psychologists.

IT KEEPS GETTING BETTER Wondering what became of Jeremy Lin following “Linsanity?” After suffering a knee injury in the spring of 2012, Jeremy was out of commission for the remainder of the season with the Knicks. He then signed a deal with the Houston Rockets, had a good run with that team for two seasons, and was traded to the Los Angeles Lakers in the summer of 2014. As of the printing of this book, Jeremy is playing for the Charlotte Hornets. He has proven he can hold his own as a point guard in the NBA, and we suspect he will continue stirring up “Linsanity” in the future.

IT KEEPS GETTING BETTER Wondering what became of Jeremy Lin following “Linsanity?” After suffering a knee injury in the spring of 2012, Jeremy was out of commission for the remainder of the season with the Knicks. He then signed a deal with the Houston Rockets, had a good run with that team for two seasons, and was traded to the Los Angeles Lakers in the summer of 2014. As of the printing of this book, Jeremy is playing for the Charlotte Hornets. He has proven he can hold his own as a point guard in the NBA, and we suspect he will continue stirring up “Linsanity” in the future.

Jeremy works with an aspiring basketball player in Taipei, Taiwan. His work with children continues through the Jeremy Lin Foundation, a nonprofit organization devoted to serving young people and their communities.

Ivonne Mosquera-

Ivonne does the triangle pose during a visit to Queenstown, New Zealand. Yoga helps develop the strength and flexibility she needs for racing, and keeps her grounded.

show what you know

Question 1

1. You want to learn how to play basketball, so you watch videos of Jeremy Lin executing plays. If your game improves as a result, this would be considered an example of:

observational learning.

association.

prosocial behavior.

your cognitive map.

a. observational learning.

Question 2

2. Bandura’s Bobo doll study shows us that observationall learning results in a wide variety of learned behaviors. Describe several types of behaviors you have learned by observing a model.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following definitions. A model is an individual or character whose behavior is being imitated. Observational learning occurs as a result of watching the behavior of others.

Question 3

3. Although Skinner believed that reinforcement is the cause of learning, there is robust evidence that reinforcement is not always necessary. This comes from experiments studying:

positive reinforcement

negative reinforcement.

latent learning.

stimulus generalization.

c. latent learning.