6.1 An Introduction to Memory

MEMORY BREAKDOWN: THE CASE OF CLIVE WEARING Monday, March 25, 1985: Deborah Wearing awoke in a sweat-

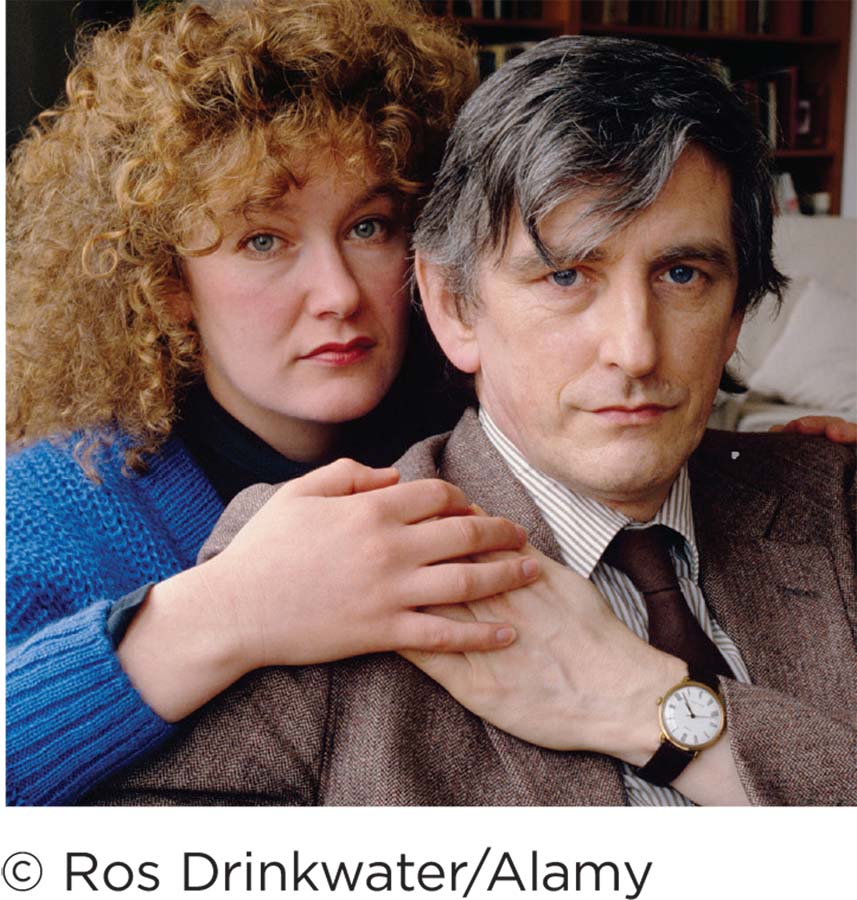

In 1985 conductor Clive Wearing (pictured here with his wife Deborah) developed a brain infection—

The doctor arrived a couple of hours later, reassured Deborah that her husband’s confusion was merely the result of sleep deprivation, and prescribed sleeping pills. Deborah came home later that day, expecting to find her husband in bed. But no Clive. She shouted out his name. No answer, just a heap of pajamas. After the police had conducted an extensive search, Clive was found when a taxi driver dropped him off at a local police station; he had gotten into the cab and couldn’t remember his address (Wearing, 2005). Clive returned to his flat (which he did not recognize as home), rested, and took in fluids. His fever dropped, and it appeared that he was improving. But when he awoke Friday morning, his confusion was so severe he could not identify the toilet among the various pieces of furniture in his bathroom. As Deborah placed urgent calls to the doctor, Clive began to drift away. He lost consciousness and was rushed to the hospital in an ambulance (Wearing, 2005; Wilson & Wearing, 1995).

Prior to this illness, Clive Wearing had enjoyed a fabulous career in music. As the Director of the London Lassus Ensemble, he spent his days leading singers and instrumentalists through the emotionally complex music of his favorite composer, Orlande de Lassus. A renowned expert on Renaissance music, Clive produced music for the prestigious British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), including that which aired on the wedding day of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer (Sacks, 2007, September 24; Wilson, Baddeley, & Kapur, 1995; Wilson, Kopelman, & Kapur, 2008). But Clive’s work—

Millions of people carry herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-

Although Deborah saw to it that Clive received early medical attention, having two doctors visit the house day and night for nearly a week, these physicians mistook his condition for the flu with meningitis-

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LO 1 Define memory.

LO 2 Identify the processes of encoding, storage, and retrieval in memory.

LO 3 Explain the stages of memory described by the information-

LO 4 Describe sensory memory.

LO 5 Summarize short-

LO 6 Give examples of how we can use chunking to improve our memory span.

LO 7 Explain working memory and how it compares with short-

LO 8 Describe long-

LO 9 Illustrate how encoding specificity relates to retrieval cues.

LO 10 Identify some of the reasons why we forget.

LO 11 Explain how the malleability of memory influences the recall of events.

LO 12 Define rich false memory.

LO 13 Compare and contrast anterograde and retrograde amnesia.

LO 14 Identify the brain structures involved in memory.

LO 15 Describe long-

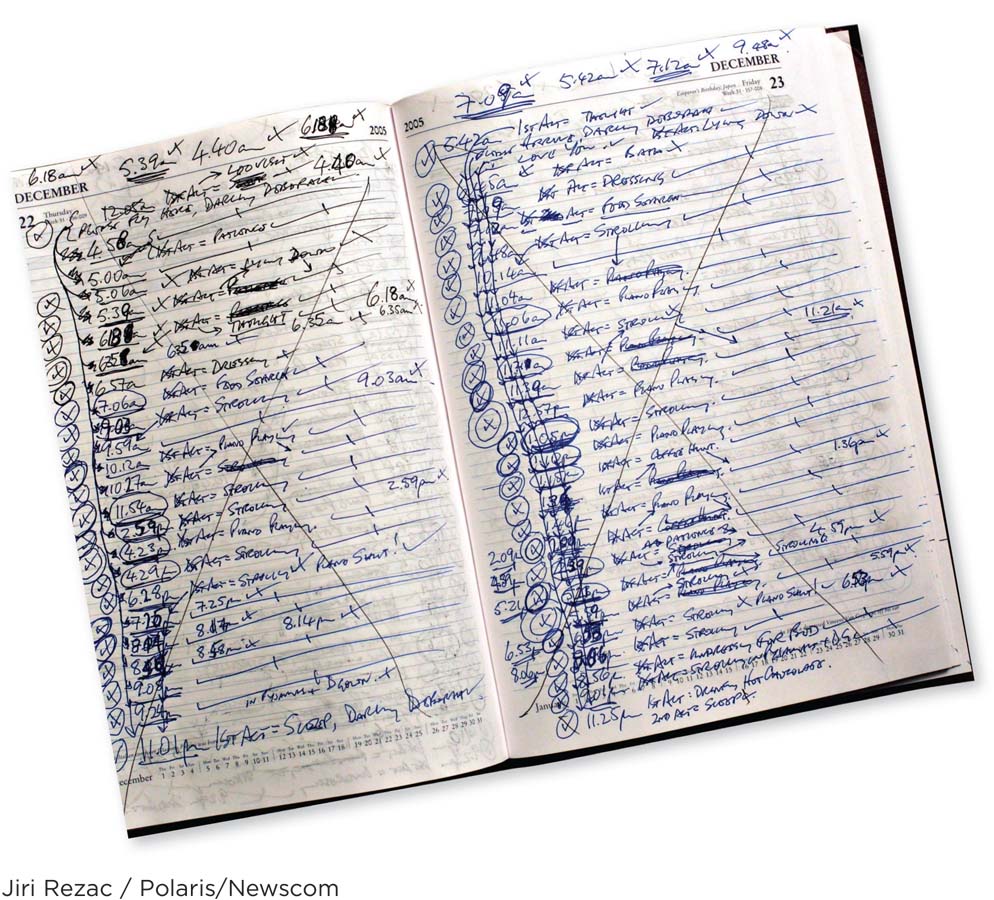

Looking at a page from Clive’s diary, you can see the fragmented nature of his thought process. He writes an entry, forgets it within seconds, and then returns to the page to start over, often writing the same thing. Encephalitis destroyed areas of Clive’s brain that are crucial for learning and memory, so he can no longer recall what is happening from moment to moment.

Clive survived, but the damage to his brain was extensive and profound; the virus had destroyed a substantial amount of neural tissue. And though Clive could still sing and play the keyboard (and spent much of the day doing so), he was unable to continue working as a conductor and music producer (D. Wearing, personal communication, June 18, 2013; Wilson & Wearing, 1995). In fact, he could barely get through day-

In the months following his illness, Clive was overcome with the feeling of just awakening. His senses were functioning properly, but every sight, sound, odor, taste, and feeling registered for just a moment, and then vanished. As Deborah described it, Clive saw the world anew with every blink of his eye (Wearing, 2005). The world must have seemed like a whirlwind of sensations, always changing, never stable. Desperate to make sense of everything, Clive would pose the same questions time and again: “How long have I been ill?” he would ask Deborah and the hospital staff members looking after him. “How long’s it been?” (Wearing, p. 181). For much of the first decade following his illness, Clive repeated the same few phrases almost continuously in his conversations with people. “I haven’t heard anything, seen anything, touched anything, smelled anything,” he would say. “It’s just like being dead” (Wearing, p. 160).

The depth of Clive’s impairment is revealed in his diary, where he wrote essentially the same entries all day long. On August 25, 1985, he wrote, “I woke at 8:50 A.M. and baught [sic] a copy of The Observer,” which is then crossed out and followed by “I woke at 9:00 A.M. I had already bought a copy of The Observer.” The next line reads, “This (officially) confirms that I awoke at 9:05 A.M. this morning” (Wearing, 2005, p. 182). Having forgotten all previous entries, Clive reported throughout the day that he had just become conscious. His recollection of writing in his journal—

The story of Clive Wearing launches our journey through memory. This chapter will take us to the opposite ends of a continuum: from memory loss to exceptional feats of remembering. We will travel to the World Memory Championships, an annual event where competitors from around the globe gather to see how many numbers, words, and images they can squeeze into their brains in 3 days. You will learn some tricks that might help you remember material for exams and everyday life: terms, concepts, passwords, pin numbers, people’s names, and where you left your keys. You, too, can develop superior memorization skills; you just have to practice using memory aids. But beware: No matter how well you exercise your memory “muscle,” it does not always perform perfectly. Like anything human, memory is prone to error.

Three Processes of Memory: Encoding, Storage, and Retrieval

LO 1 Define memory.

memory Information collected and stored in the brain that is generally retrievable for later use.

Memory refers to information the brain collects, stores, and may retrieve for later use. Much of this process has gone haywire for Clive. You may be wondering why we chose to start this chapter with the story of a person whose memory system failed. When it comes to understanding complex cognitive processes like those of memory, sometimes it helps to examine what happens when elements of the system are not working.

What is your earliest memory and how was it created? Do you know if it is accurate? And how can you recall it after so many years? Psychologists have been asking questions like these since the 1800s. Exactly how the brain absorbs information from the outside world and files it for later use is still not completely clear, but scientists have proposed many theories and models to explain how the brain processes, or works on, data on their way to becoming memories. As you learn about various theories and models, keep in mind that none of them are perfect. Rather than labeling one as right and another as wrong, most psychologists embrace a combination of approaches, taking into consideration their various strengths and weaknesses.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described the electrical and chemical processes involved in the communication between neurons. We also reported that the human nervous system, which includes the brain, contains 100 billion cells interlinked by about 100 quadrillion (1015) connections.

One often-

LO 2 Identify the processes of encoding, storage, and retrieval in memory.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapters 2 and 3, we described how sensory information is taken in by sensory receptors and transduced; that is, transformed into neural activity. Here, we explore what happens after transduction, when information is processed in the memory system.

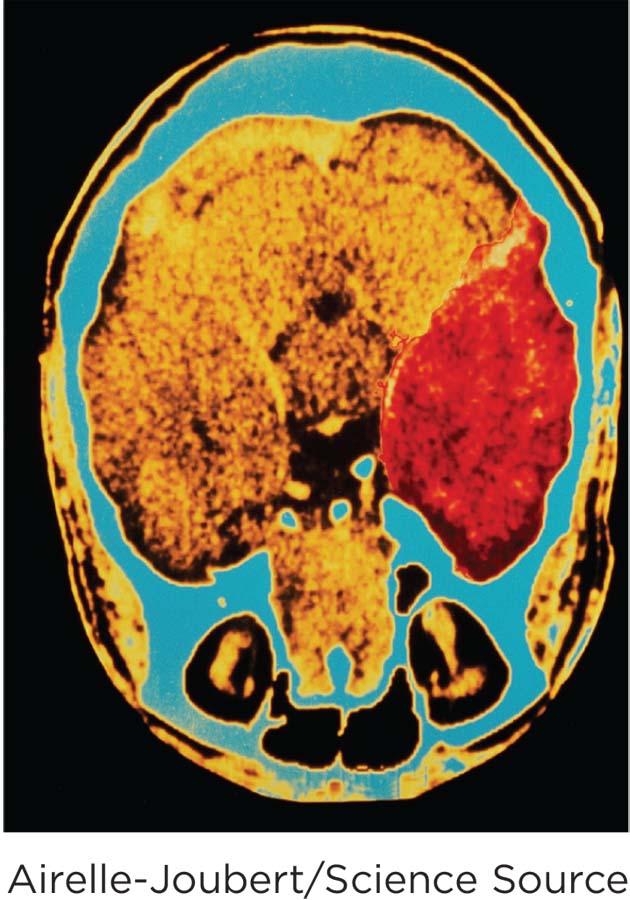

encoding The process through which information enters our memory system.

The red area in this computerized axial tomography (CAT or CT) scan reveals inflammation in the temporal lobe. The cause of this swelling is herpes simplex virus, the same virus responsible for Clive’s illness. Many people carry this virus (it causes cold sores), but herpes encephalitis is extremely rare, affecting as few as 1 in 500,000 people annually (Sabah et al., 2012). Even with early treatment, this brain infection frequently leaves its victims with cognitive damage (Kennedy & Chaudhuri, 2002).

ENCODING During the course of a day, we are bombarded with information coming from all of our senses and internal data from thoughts and emotions. Some of this information we will remember, but the majority of it will not be retained for very long. What is the difference between what is kept and what is not? Most psychologists agree that it all starts with encoding, the process through which information enters our memory system. Think about what happens when you pay attention to an event unfolding before you; stimuli associated with that event (sights, sounds, smells) are taken in by your senses and then converted to neural activity that travels to the brain. Here, the neural activity continues, at which point the information takes one of two paths: Either it enters our memory system (it is encoded to be stored for a longer period of time) or it slips away. For Clive Wearing, much of this information slips away.

storage The process of preserving information for possible recollection in the future.

STORAGE For information that is successfully encoded, the next step is storage. Storage is exactly what it sounds like: preserving information for possible recollection in the future. Before Clive Wearing fell ill, his memory was excellent. His brain was able to encode and store a variety of events and learned abilities. Following his bout with encephalitis, however, his ability for long-

retrieval The process of accessing information encoded and stored in memory.

RETRIEVAL After information is stored, how do we access it? Perhaps you still have a memory of your first-

Before taking a closer look at the three processes of memory—

MEET THE MEMORY ATHLETES The 18th Annual World Memory Championships had officially kicked off. Dorothea Seitz felt her heart pound as she flipped over her memorization sheet. The page was filled with row upon row of black-

MEET THE MEMORY ATHLETES The 18th Annual World Memory Championships had officially kicked off. Dorothea Seitz felt her heart pound as she flipped over her memorization sheet. The page was filled with row upon row of black-

Competitors at the 2013 World Memory Championships study stacks of playing cards. Many wear earmuffs and other devices to block out background noises that might interfere with their concentration.

Memory master Dominic O’Brien took 54 decks of playing cards and memorized their correct order after flipping through them just once. By practicing memory techniques, Dominic went from being a person with an average memory to an eight-

Dorothea was the reigning junior champion, and she had come to defend her title. Sitting in that same London conference room were 73 other contestants from all over the world, including most of the hotshots in memory sport. Many wore large ear plugs or earmuffs to cancel out any noises that might derail their train of thought. Others donned dark glasses with tiny holes cut out of the centers, or side blinders like the kind racehorses wear—

When the 15 minutes were up, contest supervisors circulated the room collecting memorization sheets and distributing “recall sheets”—pieces of paper with the same images arranged in a different order. The contestants had only 30 minutes to unscramble them. Speeding through the recall phase of the event, Dorothea managed to remember 214 images. That put her in fourth place overall—

Dorothea had started the competition strong, but there were still nine events to go. The competitors would spend the next 3 days memorizing meaningless strings of numbers, random lists of words, imaginary historic dates, and other pieces of contrived “information.”

MEMORY COMPETITORS AND THE REST OF US The brains of memory champions are not wired in a special way; these are regular people who have trained themselves to excel in memory. Just ask eight-

One small study actually compared memory competitors to “normal” people and found nothing extraordinary about their intelligence or brain structure. What they did find was heightened activity in specific brain areas (particularly in regions used for spatial memory). This activity seemed to be associated with the use of a method for remembering items by associating them with an imagined “journey” (Maguire, Valentine, Wilding, & Kapur, 2003). As it turns out, memory champions like Dorothea and Dominic rely heavily on this type of imagined journey, which is rich with visual images. We will learn about this memory aid later in the chapter, when we discuss memory improvement, but first we must get a grasp of how the entire system works.

The Information-Processing Model of Memory

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described the importance of using theories and models to organize and conceptualize observations. In this chapter, we present several of these to explain the human memory system.

LO 3 Explain the stages of memory described by the information-

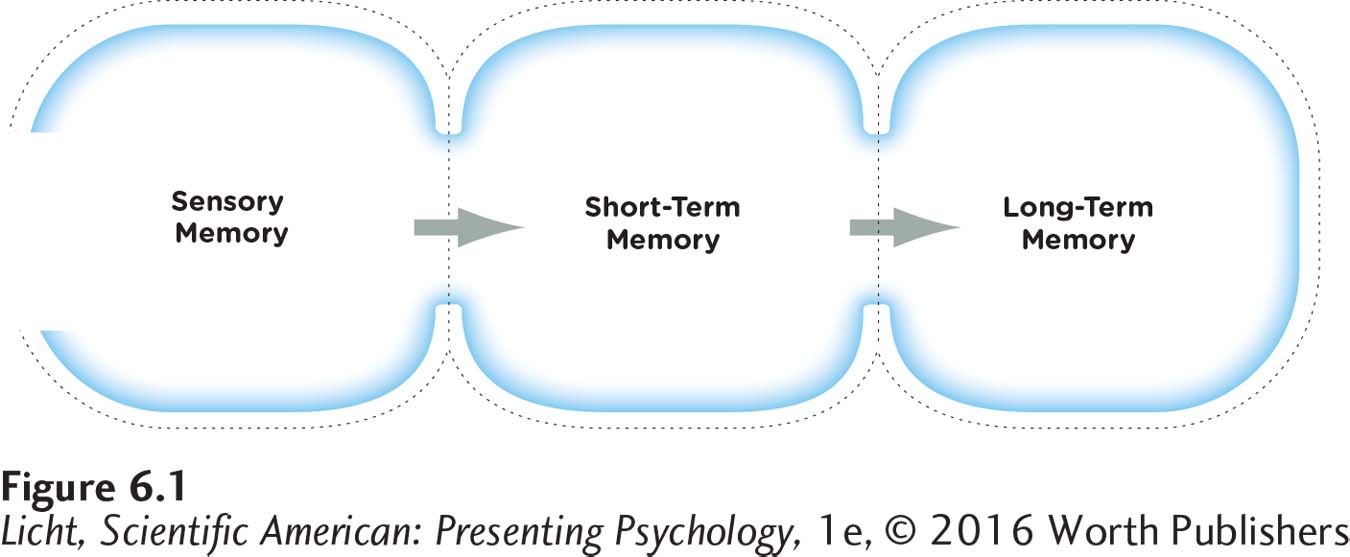

Psychologists employ several models to explain how the memory system is organized. Among the most influential is the information-

Synonyms

sensory memory sensory register

sensory memory A stage of memory that captures near-

short-

long-

According to the information-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we defined sensation as the process by which receptors receive and detect stimuli. Perception is the process by which sensory data are organized to provide meaningful information. Some critics of the information-

Note: Quotations attributed to Dorothea Seitz are personal communications.

The information-

Levels of Processing

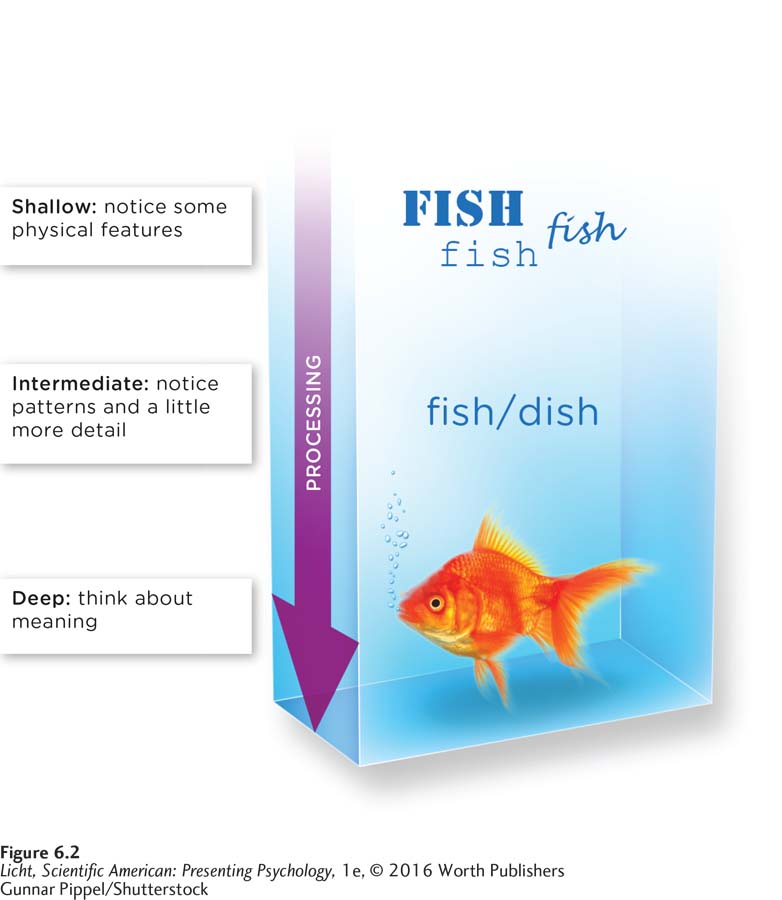

Information can be processed along a continuum from shallow to deep, affecting the probability of recall. Shallow processing, in which only certain details like the physical appearance of a word might be noticed, results in brief memories that may not be recalled later. We are better able to recall information we process at a deep level, thinking about meaning and tying it to memories we already have.

Another way to conceptualize memory is from a processing standpoint. To what degree does information entering the memory system get worked on? According to the levels of processing framework, there is a “hierarchy of processing stages” that corresponds to different depths of information processing (Craik & Lockhart, 1972). Thus, processing can occur along a continuum from shallow to deep (Figure 6.2). Shallow-

Fergus Craik and Endel Tulving explored levels of processing in their classic 1975 study. After presenting college students with various words, the researchers asked them yes or no questions, prompting them to think about and encode the words at three different levels: shallow, intermediate, and deep. The shallow questions required the students to study the appearance of the word: “Is the word in capital letters?” The intermediate-

Ask several people to try to remember the name “Clive Wearing.” (1) Tell some of them to picture it written out in uppercase letters (CLIVE WEARING). (2) Tell others to imagine what it sounds like (Clive Wearing rhymes with dive daring). (3) Ask a third group to contemplate its underlying significance (Clive Wearing is the musician who suffers from an extreme case of memory loss). Later, test each person’s memory for the name and see if a deeper level of processing leads to better encoding and a stronger memory.

try this

Most people have the greatest success with (3) deep processing, but it depends somewhat on how they are prompted to retrieve information. For example, if someone asks you to remember any words that rhyme with “dive daring,” the name “Clive Wearing” will probably pop into your head regardless of whether you used deep processing.

The levels of processing model helps us understand why testing, which often requires you to connect new and old information, can improve memory and help you succeed in school. Research strongly supports the idea that “testing improves learning,” as long as the stakes are low (Dunlosky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan, & Willingham, 2013). The Show What You Know and Test Prep resources in this textbook are designed with this in mind. Repeated testing, or the testing effect, results in a variety of benefits: better information retention; identification of areas needing more study; and increased self-

show what you know

Question 1

1. __________ refers to the information that your brain collects, stores, and may use at a later time.

Memory

Question 2

2. __________ is the process whereby information enters the memory system.

Retrieval

Encoding

Communication

Spatial memory

b. Encoding

Question 3

3. After suffering from a devastating illness, Clive Wearing essentially lost the ability to use which of the following stages of the information-

long-

term memory sensory memory

memory for keywords

sensory register

a. long-

Question 4

4. How might you illustrate shallow processing versus deep processing as it relates to studying?

Paying little attention to data entering our sensory system results in shallow processing. For example, you remember seeing a word that has been boldfaced in the text while studying. You might even be able to recall the page that it appears on, and where on the page it is located. Deeper-