7.4 Intelligence

Orlando Bloom was first diagnosed with dyslexia at the age of 7. Fortunately, he had a mother who believed in him and a school that allowed him to leave campus and attend special classes to address the issue (Child Mind Institute, 2010, October 18; Ryon, 2011, October 3). But many children are not identified as having dyslexia until they have lost considerable academic ground. Even those who receive an early diagnosis may not get into effective reading programs. Despite such challenges, people with dyslexia can be very successful.

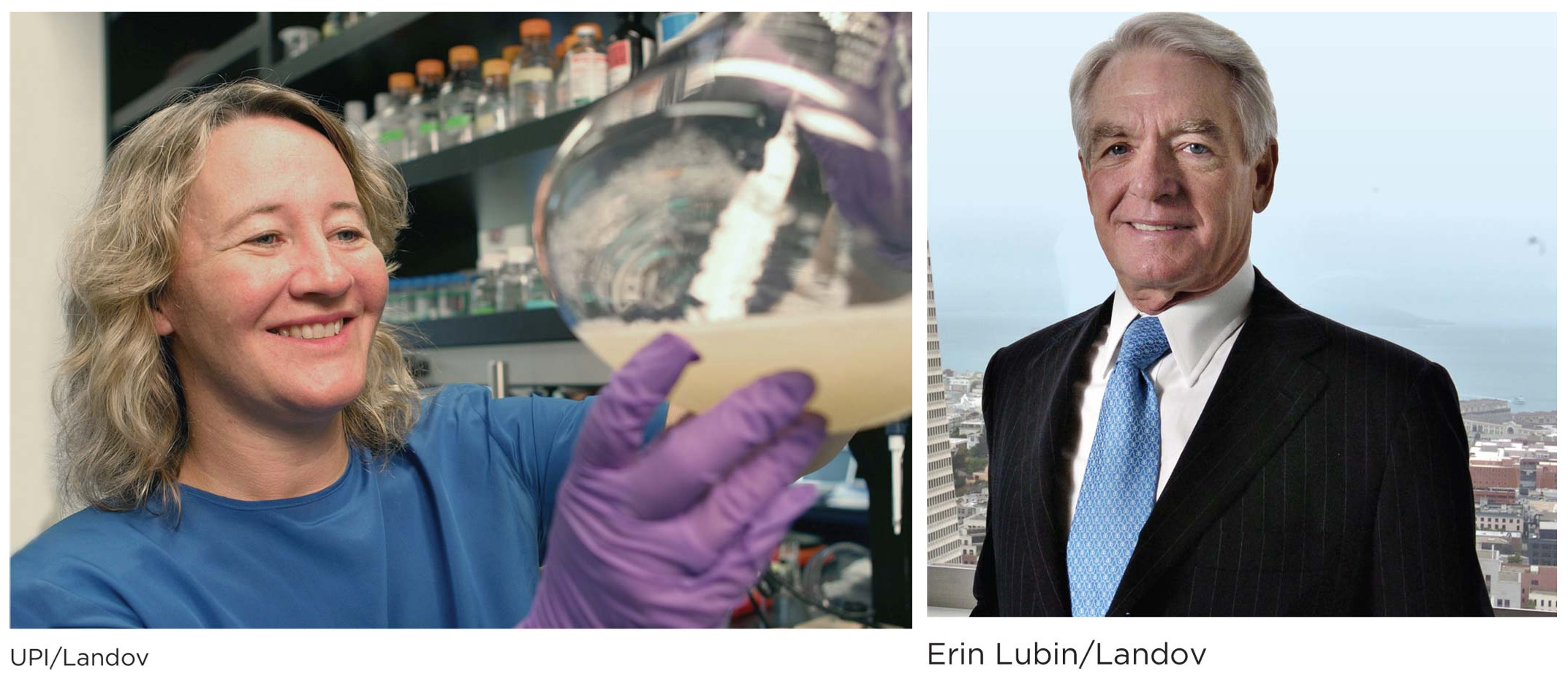

Many great intellectuals have battled dyslexia, among them Nobel Prize winners Pierre Curie, Archer Martin, and Carol Greider (Allen, 2009, October 30); financier Charles Schwab; acclaimed writer John Irving; and the president of the esteemed Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Delos Cosgrove (Shaywitz, 2003). Dyslexia, it turns out, is not a gauge of intelligence (Ferrer, Shaywitz, Holahan, Marchione, & Shawyitz, 2010).

Nobel Prize winner Carol Greider (left) and financier Charles Schwab (right) are just two examples of successful people with dyslexia. There are many others, including Jay Leno, Tom Cruise, Anderson Cooper, and Ingvar Kamprad, the creator of IKEA (Allen, 2009, October 30; Turgeon, 2011, July 14).

What Is Intelligence?

LO 10 Examine and distinguish among various theories of intelligence.

intelligence Innate ability to solve problems, adapt to the environment, and learn from experiences.

Maasai children in Kenya go through the motions of starting a fire. Definitions of intelligence vary according to culture. In the United States, intelligence is typically associated with high grades and test scores. Elsewhere in the world, being “smart” may have more to do with knowing how to survive and stay healthy.

Generally speaking, intelligence is one’s innate ability to solve problems, adapt to the environment, and learn from experiences. Intelligence relates to a broad array of psychological processes, including memory, learning, perception, and language, and how it is defined may sometimes depend on the variable being measured.

In the United States, intelligence is often associated with “book smarts.” We think of “intelligent” people as those who score high on tests measuring academic abilities. But intelligence is more complicated than that—

We do know that intelligence is, to a certain degree, a cultural construct. So although people in the United States tend to equate intelligence with school smarts, this is not the case everywhere in the world. Children living in a village in Kenya, for example, grow up using herbal medicine to treat parasitic diseases in themselves and others. Identifying illness and developing treatment strategies is a regular part of life. These children would score much higher on tests of intelligence relating to practical knowledge than on tests assessing vocabulary (Sternberg, 2004). Even within a single culture, the meaning of intelligence changes across time. “Intelligence” for modern Kenyans may differ from that of their 14th-

As we explore the theories of intelligence below, please keep in mind that intelligence does not always go hand in hand with intelligent behavior. People can score high on intelligence measures but exhibit a low level of judgment.

general intelligence (g factor) A singular underlying aptitude or intellectual competence that drives abilities in many areas, including verbal, spatial, and reasoning abilities.

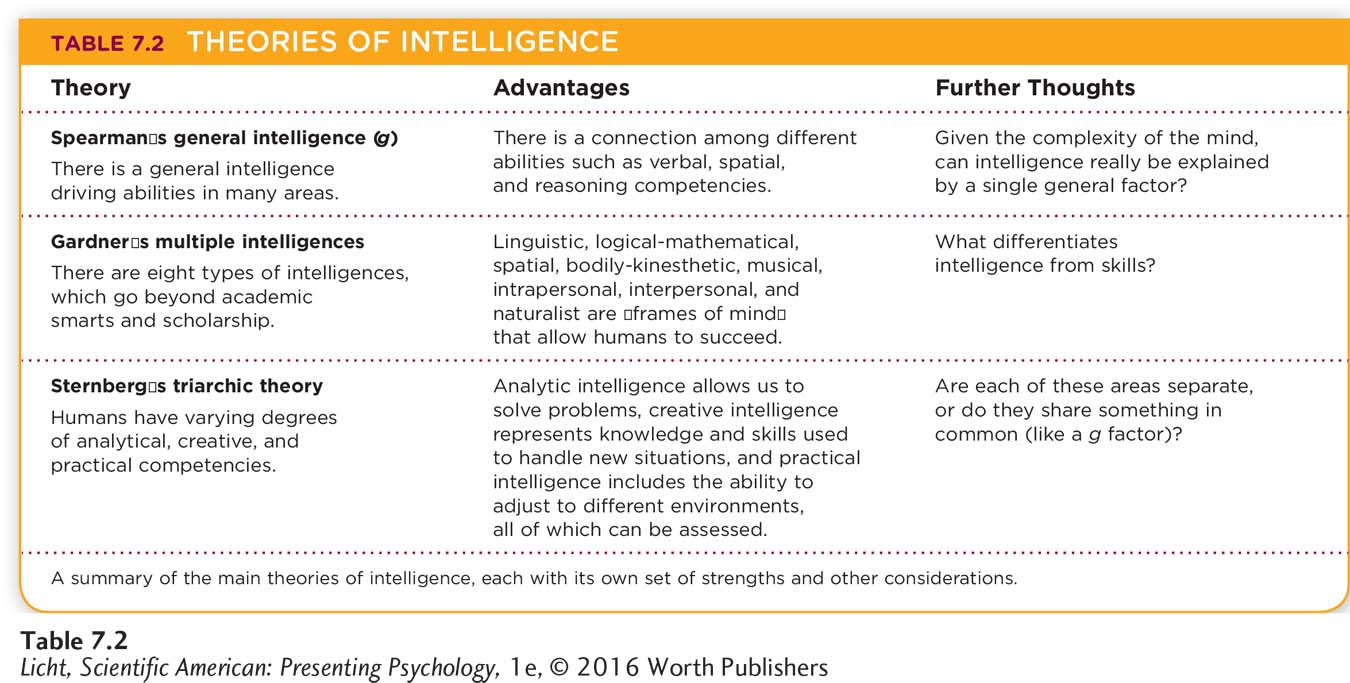

THE g FACTOR Very early in the history of intelligence measurement, Charles Spearman (1863–

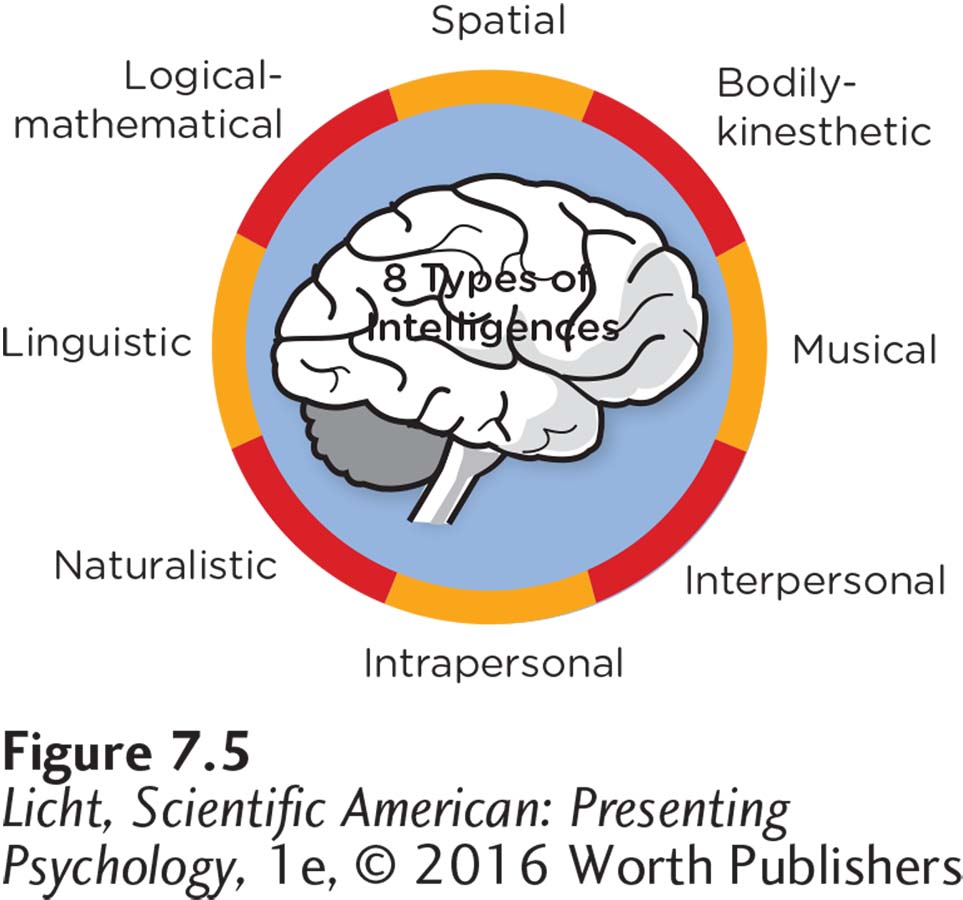

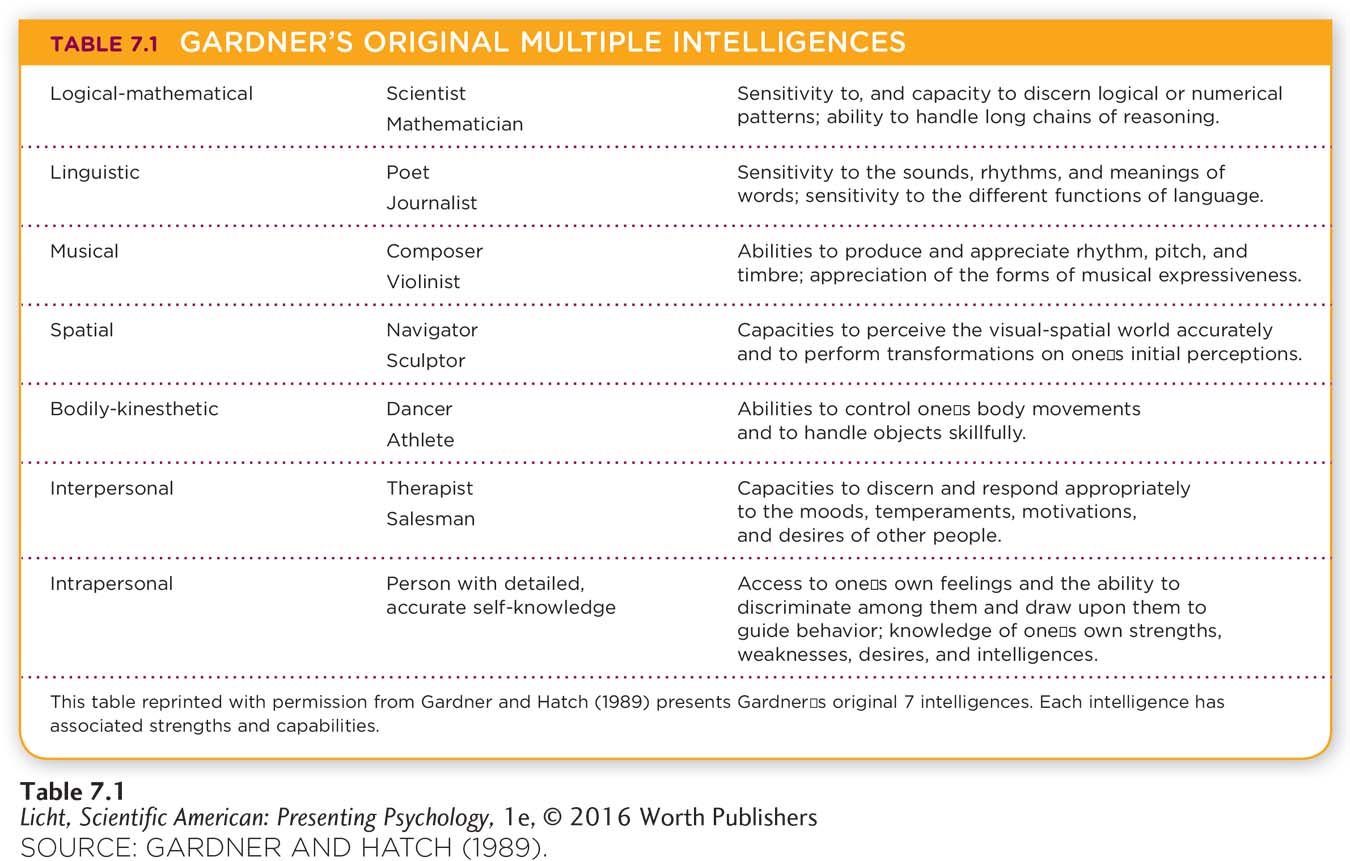

MULTIPLE INTELLIGENCES Howard Gardner (1999, 2011) suggested that intelligence can be divided into multiple intelligences (Figure 7.5). According to Gardner, there are eight types of intelligences or “frames of mind”: linguistic (verbal), logical-

According to Gardner (2011), partial evidence for multiple intelligences comes from studying people with brain damage. Some mental capabilities are lost, whereas others remain intact, suggesting that they are really distinct categories. Further evidence for multiple intelligences (as opposed to just a g factor) comes from observing people with savant syndrome. Individuals with savant syndrome generally score low on intelligence tests but have some area of extreme singular ability (calendar calculations, art, mental arithmetic, and so on). Interestingly, the majority of individuals with savant syndrome are male (Treffert, 2009).

Some psychologists question whether these abilities qualify as intelligence, as opposed to skills. Critics contend that there is little empirical support for the existence of multiple intelligences (Geake, 2008; Waterhouse, 2006).

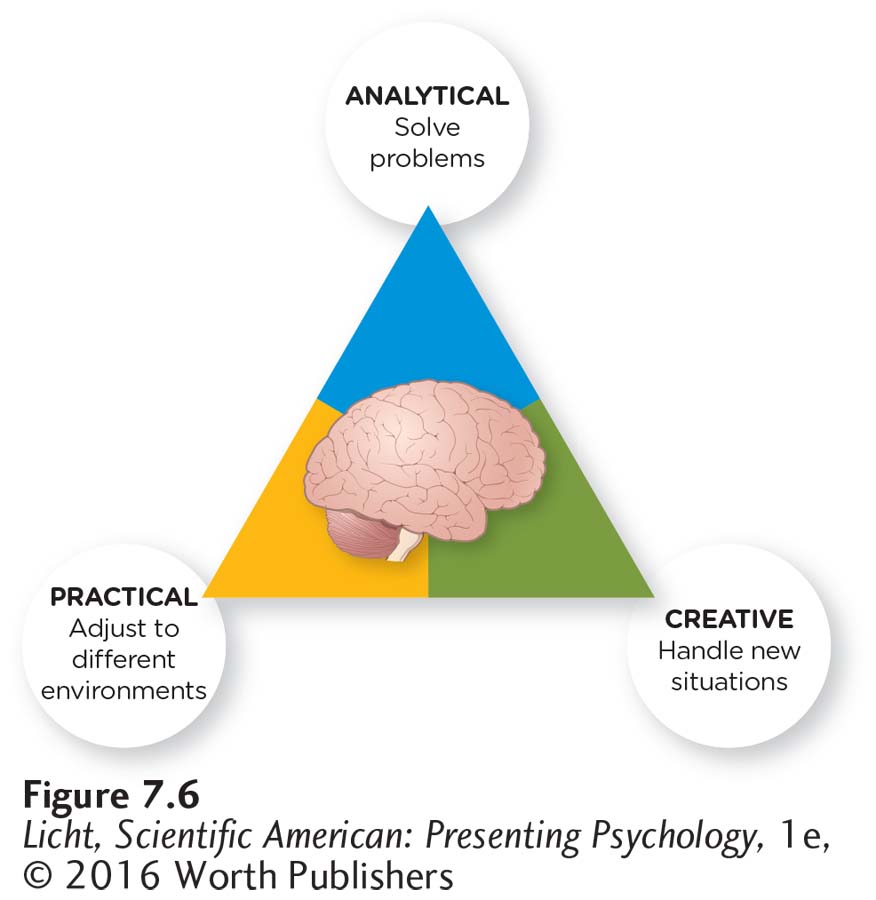

triarchic theory of intelligence (trī-är-

THE TRIARCHIC THEORY OF INTELLIGENCE Robert Sternberg (1988) proposed three kinds of intelligence. Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence (trī-är-

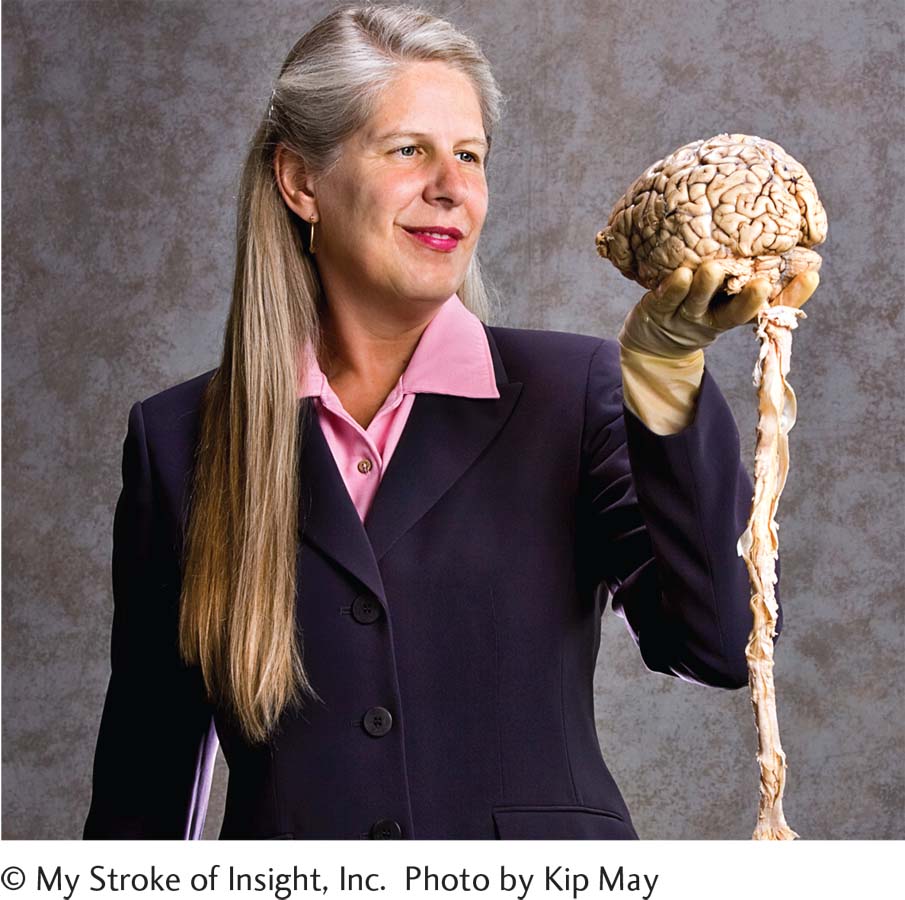

Let’s take a moment and see how the triarchic theory of intelligence relates to Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor. Following the stroke, Dr. Jill struggled with what Sternberg referred to as analytic intelligence, or the ability to solve problems. She did, however, demonstrate evidence of creative intelligence, using knowledge and skills to handle new situations. While recovering at the hospital, Dr. Jill had routine meetings with a doctor who regularly assigned her three items to remember. On his way out, he would ask her to recall these three items. Since the stroke had dismantled much of Dr. Jill’s memory system, she found this assignment nearly impossible. But on one particular day, she was dead set on remembering the assigned items: firefighter, apple, and 33 Whippoorwill Drive. Using all her available brain power, she recited the words over and over in her mind, but when the doctor finally quizzed her, she could not remember the “33” part of 33 Whippoorwill Drive. She did, however, come up with a creative theoretical solution: She told the doctor that she would walk down Whippoorwill Drive and knock on every door until she identified the house (Taylor, 2006).

Dr. Jill also maintained some degree of practical intelligence, the ability to adjust to her surroundings. Her world was thrown into turmoil by the stroke, but she developed pragmatic coping mechanisms to deal with the novelty of it all. Quickly realizing that talking to people and watching television caused mental exhaustion, she and G.G. decided to limit these overstimulating activities so that her brain could heal in tranquility. This practical strategy turned out to be a key component of her recovery (Taylor, 2006).

Needless to say, there are different ways to conceptualize intelligence (Table 7.2), none of which appear to be categorically “right” or “wrong.” Given these varied approaches, you might expect there are also many tools to measure intelligence. Let’s explore several ways psychologists assess intellectual ability.

Measuring Brainpower

LO 11 Describe how intelligence is measured and identify important characteristics of assessment.

aptitude An individual’s potential for learning.

achievement Acquired knowledge, or what has been learned.

Recall that Orlando was 7 years old when he was diagnosed with dyslexia. Around the same time, he took an intelligence test and scored very high (Child Mind Institute, 2010, October 18). Tests of intelligence generally aim to measure aptitude, or a person’s potential for learning. On the other hand, measures of achievement are designed to assess acquired knowledge (what a person has learned). Many brilliant people with dyslexia have performed poorly on achievement tests but very well on aptitude tests, demonstrating normal to high intelligence. The writer John Irving, for example, got a low score on the verbal portion of the SAT, and the renowned physician Delos Cosgrove performed poorly on the Medical College Admission Test (Shaywitz, 2003). Fortunately, they did not allow a single test to deter them. The line between aptitude and achievement tests is somewhat hazy, however; most tests are not purely one or the other.

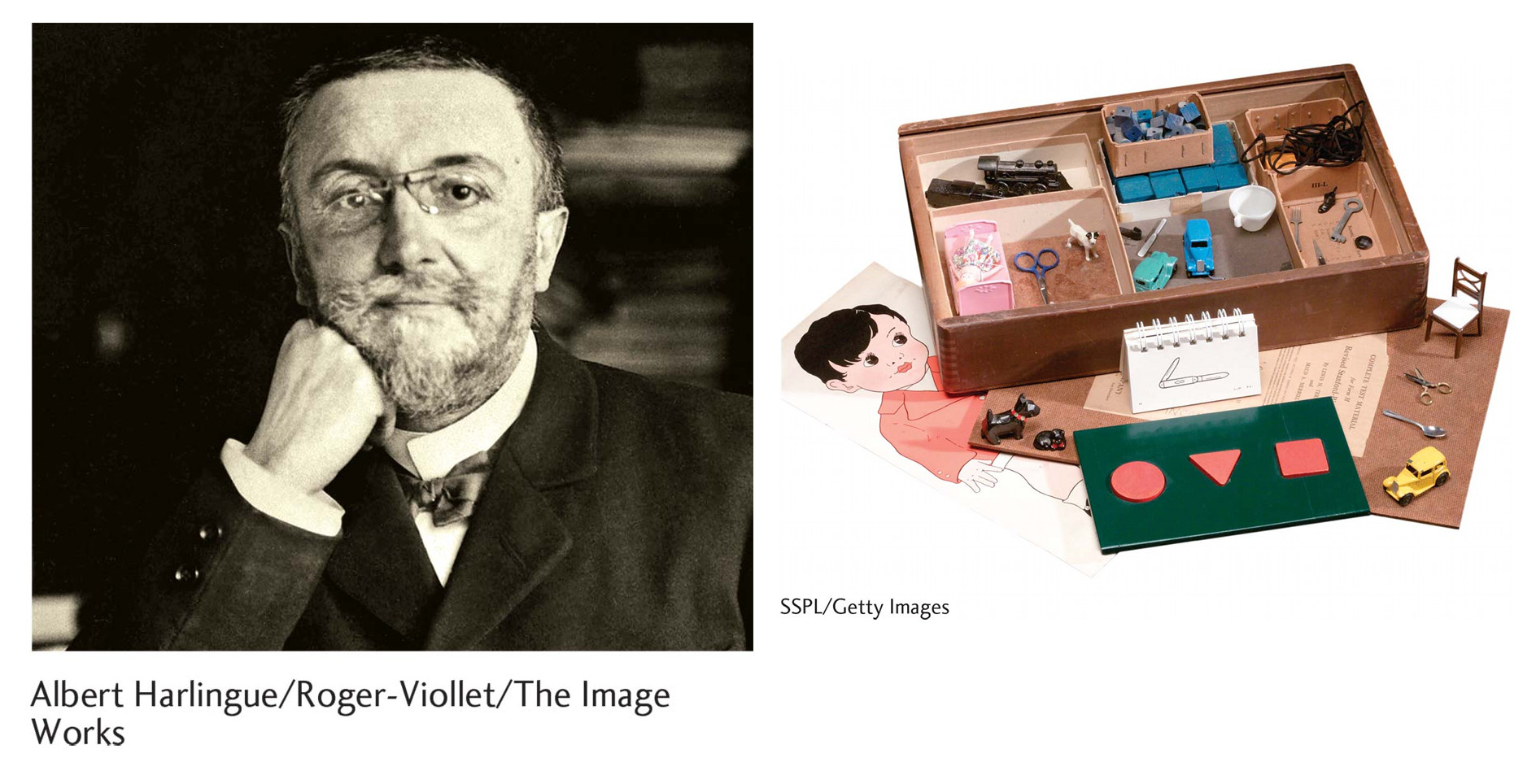

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INTELLIGENCE TESTING Intelligence testing is more than a century old. In 1904 psychologist Alfred Binet (1857–

Binet worked with one of his students, Théodore Simon (1872–

mental age (MA) A score representing the mental abilities of an individual in relation to others of a similar chronological age.

Binet and Simon assumed that children generally follow the same path of intellectual development. Their primary goal was to compare a child’s mental ability with the mental abilities of other children of the same age. They would determine the mental age (MA) of a child by comparing his performance to that of other children in the same age category. For example, a 10-

intelligence quotient (IQ) A score from an intelligence assessment; originally based on mental age divided by chronological age, multiplied by 100.

One of the problems with relying on mental age as an index is that it cannot be used to compare intelligence levels across age groups. For example, you can’t use mental age to compare the intelligence levels of an 8-

This method does not apply to adults, however. It wouldn’t make sense to give a 60-

French psychologist Alfred Binet collaborated with one of his students, Théodore Simon, to create a systematic assessment of intelligence. The materials pictured here come from Lewis Terman and Maude Merrill’s 1937 version of Binet and Simon’s test. Using these materials, the test administrator prompts the test taker with statements such as “Point to the doll’s foot,” or “What advantages does an airplane have over a car?” (Sattler, 1990).

THE STANFORD–

THE WECHSLER TESTS In the late 1930s, David Wechsler began creating intelligence tests for adults (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997). Although many had been using the Stanford–

The Wechsler assessments of intelligence consist of a variety of subtests designed to measure different aspects of intellectual ability. The 10 subtests on the WAIS–

Let’s Test the Intelligence Tests

Tests such as the SAT and ACT are called achievement tests because they are geared toward measuring learned knowledge, as opposed to innate ability. These tests are also standardized, making it possible to compare scores of people who are demographically similar.

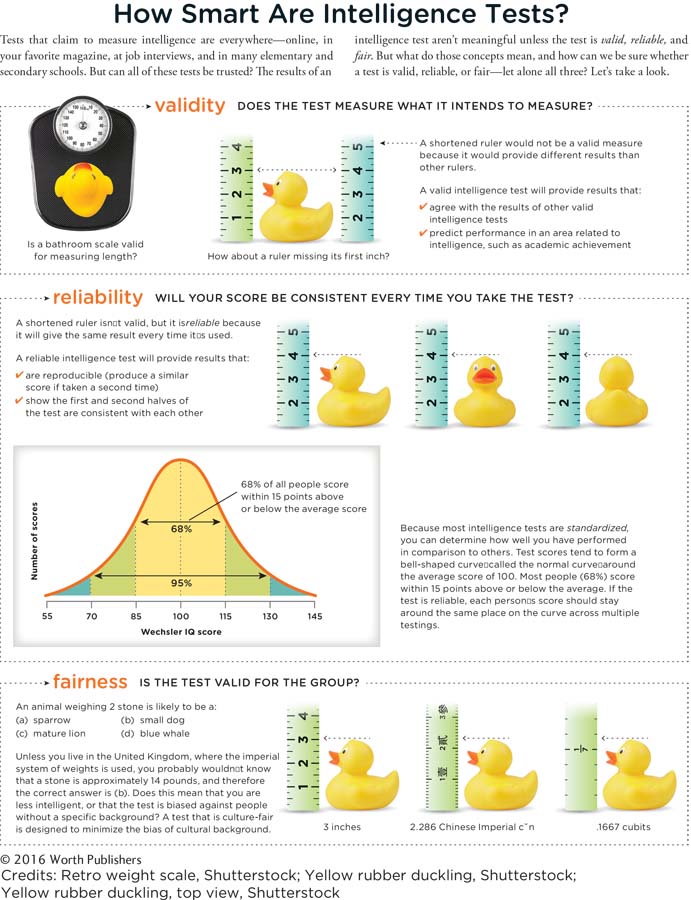

As you read about the history of intelligence assessment, did you wonder how effective those early tests were? We hope so, because this would indicate you are thinking critically. Psychologists make great efforts to ensure the accurate assessment of intelligence, paying close attention to three important characteristics: validity, reliability, and standardization.

validity The degree to which an assessment measures what it intends to measure.

VALIDITY Validity is the degree to which an assessment measures what it intends to measure. We can assess the validity of a measure by comparing its results to those of other assessments that have been found to measure the factor of interest. In addition, we determine the validity of an assessment by seeing if it can predict what it is designed to measure, or its predictive validity. Thus, to determine if an intelligence test is valid, we would check to see if the scores it produces are consistent with those of other intelligence tests. A valid intelligence test should also be able to predict future performance on tasks related to intellectual ability.

reliability The ability of an assessment to provide consistent, reproducible results.

RELIABILITY Another important characteristic of assessment is reliability, the ability of a test to provide consistent, reproducible results. If given repeatedly, a reliable test will continue producing the same types of scores. If we administer an intelligence test to an individual, we would expect (if it is reliable) that the person’s scores will remain consistent across time. We can also determine the reliability of an assessment by splitting the test in half and then determining whether the findings of the first and second halves of the test agree with each other. It is important to note that it is possible to have a reliable test that is not valid. For this reason, we always have to determine both reliability and validity.

standardization Occurs when test developers administer a test to a large sample and then publish the average scores for specified groups.

STANDARDIZATION In addition to being valid and reliable, a good intelligence test provides standardization. Perhaps you have taken a test that measured your achievement in a particular area (for example, an ACT or SAT), or an aptitude test to measure your innate abilities (for example, an IQ test). Upon receiving your scores, you may have wondered how you performed in comparison to other people in your class, college, or state. Most aptitude and achievement tests allow you to make these judgments through the use of standardization. Standardization occurs when test developers administer a test to a large sample of people and then publish the average scores, or norms, for specified groups. The sample must be representative of the population of interest; that is, it must include a variety of individuals who are similar to the population using the test. This allows you to compare your own score with people of the same age, gender, socioeconomic status, or region. Test norms permit evaluation of the relative performance (often provided as percentiles) of an individual compared to others with similar characteristics.

It is also critical that assessments are given and scored using standard procedures. This ensures that no one is given an unfair advantage or disadvantage. Intelligence tests are subject to tight control. The public does not have access to the questions or answers, and all testing must be administered by a professional. What about those IQ tests found on the Internet? They simply are not valid due to lack of standardization.

normal curve Depicts the frequency of values of a variable along a continuum; bell-

Synonyms

normal curve normal distribution

THE NORMAL CURVE Have you ever wondered how many people in the population are really smart? Or perhaps how many people have average intelligence? With aptitude tests like the Wechsler assessments and the Stanford–

INFOGRAPHIC 7.4

The normal curve shown in Infographic 7.4 portrays the distribution of scores for the Wechsler tests. As you can see, the mean or average score is 100. As you follow the horizontal axis, notice that the higher and lower scores occur less and less frequently in the population. A score of 145 or 70 is far less common than a score of 100, for example.

One final note about the normal curve is that it applies to a variety of traits, including IQ, height, weight, and personality characteristics, and that we use it to make predictions about these traits. Consult Appendix A for more information on the normal curve and a variety of other topics associated with statistics.

BUT ARE THEY FAIR? A major concern with intelligence tests is that IQ scores consistently differ across certain groups of people. For example, researchers have reported that Black Americans in general score lower on intelligence tests than do White Americans. The difference in the average of these two groups is around 10 to 15 IQ points (Ceci & Williams, 2009; Dickens & Flynn, 2006). Group differences are also apparent for East Asians, who score around 6 points higher than average White Americans, and for Hispanics, who score around 10 points lower than average White Americans (Rushton & Jensen, 2010). Although researchers disagree about what causes these gaps in IQ scores, they are in general agreement that there is no evidence to support a “genetic hypothesis” (Nisbett et al., 2012). Instead, researchers generally attribute these group differences to environmental factors.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 6, we discussed the biology of memory, exploring areas of the brain responsible for memory formation and storage (hippocampus, cerebellum, and amygdala) as well as changes at the level of the neuron (long-

The evidence for environmental influence is strong and points to a variety of factors that contribute to this gap in IQ scores. One adoption study, for example, found that Black and mixed-

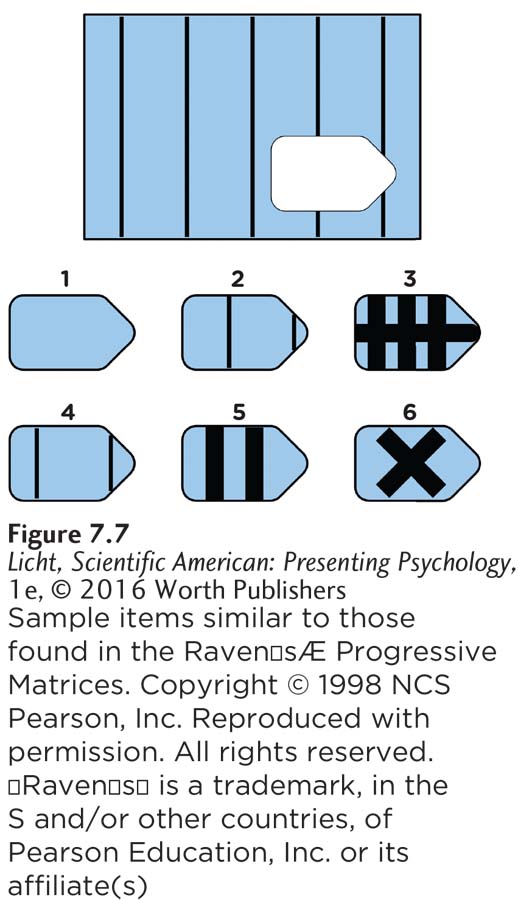

The Raven’s Progressive Matrices test is used to assess components of nonverbal intelligence. For the sample question pictured here, the test taker is required to choose the item that completes the matrix pattern. The correct answer is choice 2. This type of test is generally considered culturally fair, meaning it does not favor certain cultural groups over others.

Socioeconomic status (SES) is yet another important variable to consider. The disproportionate percentage of minorities in the lower strata may, in fact, mask the critical issue of environmental factors and their relationship with IQ. For example, children raised in homes with lower SES tend to watch more TV, have less access to books and technology, and are not read to as often. In addition, individuals with lower SES frequently live in disadvantaged neighborhoods and have limited access to quality schools (Hanscombe et al., 2012).

culture-

CULTURE-

To address these problems, psychologists have tried to create culture-

Ultimately, IQ tests are good at predicting academic success. They are highly correlated with SATs, ACTs, and GREs, for example, and the correlations are stronger for the higher and lower ranges of IQ scores. Strong correlations help us make predictions about future behavior. Researchers have found, however, that self-

The study of intelligence is far from straightforward. Assessing a concept with no universally accepted definition is not an easy task, but these tests do serve useful purposes. The key is to be mindful of their limitations, while appreciating their ability to measure an array of cognitive abilities.

The Diversity of Human Intelligence

Chinese conductor Hu Yizhou rehearses for an upcoming concert in Korea. Yizhou, who has Down syndrome, is part of the China Disabled Peoples Performing Art Troupe.

Once called mental retardation, intellectual disability consists of a delay in thinking, intelligence, and social and practical skills that is evident before age 18. Psychologists can assess intellectual functioning with IQ scores; for example, disability is identified as an IQ below approximately 70 on the Wechsler tests. It can also be assessed in terms of one’s ability to adapt; for example, being able to live independently, and understanding number concepts, money, and hygiene. Although intellectual disability is the preferred term, the phrase “mental retardation” is still used in most laws and policies relating to intellectual disability (for example, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2004; Social Security Disability Insurance; and Medicaid Home and Community Based Waiver) (Schalock et al., 2010).

There are many causes of intellectual disability, but we cannot always pinpoint them. According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), nearly half of intellectual disability cases have unidentifiable causes (Schalock et al., 2010). We do know the causes for Down syndrome (an extra chromosome in what would normally be the 21st pair), fetal alcohol syndrome (exposure to alcohol while in utero), and fragile X syndrome (a defect in a gene on the X chromosome leading to reductions in protein needed for development of the brain). There are also known environmental factors, such as lead and mercury poisoning, lack of oxygen at birth, various diseases, and exposure to drugs during fetal development.

gifted Highly intelligent; defined as having an IQ score of 130 or above.

At the other end of the intelligence spectrum are the intellectually gifted, those who have IQ scores of 130 or above. Above 140, one is considered a “genius.” As you might imagine, very few people—

TERMAN’S STUDY OF THE GIFTED American psychologist Lewis Terman was interested in discovering if gifted children could function successfully in adulthood. His work led to the longest-

emotional intelligence The capacity to perceive, understand, regulate, and use emotions to adapt to social situations.

LIFE SMARTS The ability to function in everyday life also is influenced by emotional intelligence (Goleman, 1995). Emotional intelligence is the capacity to perceive, understand, regulate, and use emotions to adapt to social situations. People with emotional intelligence use information about their emotions to direct their behavior in an efficient and creative way (Salovey, Mayer, & Caruso, 2002). They are self-

As you may have observed in your own life, people display varying degrees of emotional intelligence. Where does this diversity in emotional intelligence—

Nature and Nurture

Why Dyslexia?

We don’t have access to Orlando Bloom’s genetic code, and we certainly are not in a position to speculate on what caused his dyslexia. In some cases, however, it appears that reading difficulties are written into the genes. Dyslexia is, to a certain extent, inherited. Some of the earliest dyslexia researchers noticed that the condition runs in families, and many studies have confirmed this observation (Fisher & DeFries, 2002). If you have dyslexia and you have children, there is a good chance one of your kids will develop it as well.

We don’t have access to Orlando Bloom’s genetic code, and we certainly are not in a position to speculate on what caused his dyslexia. In some cases, however, it appears that reading difficulties are written into the genes. Dyslexia is, to a certain extent, inherited. Some of the earliest dyslexia researchers noticed that the condition runs in families, and many studies have confirmed this observation (Fisher & DeFries, 2002). If you have dyslexia and you have children, there is a good chance one of your kids will develop it as well.

But genes aren’t the whole story. Your genetic code provides a blueprint for the development of a human brain and body—

DYSLEXIA CAN BE TRACED TO ATYPICAL CONNECTIONSIN THE BRAIN. . . .

The nurture side of the coin even has value for adults, whose brains are still receptive to training. Dyslexia can be traced to atypical connections in the brain, and, specifically, decreased activity in various areas, including the left parietotemporal region. fMRI research suggests this region can be awakened when a person with dyslexia receives intensive phonological training and learns to read more efficiently (Eden et al., 2004). The takeaway: Nature isn’t everything. With proper intervention (nurture), the brain of someone with dyslexia can begin to behave more like the brain of an average reader (Shaywitz, 2003).

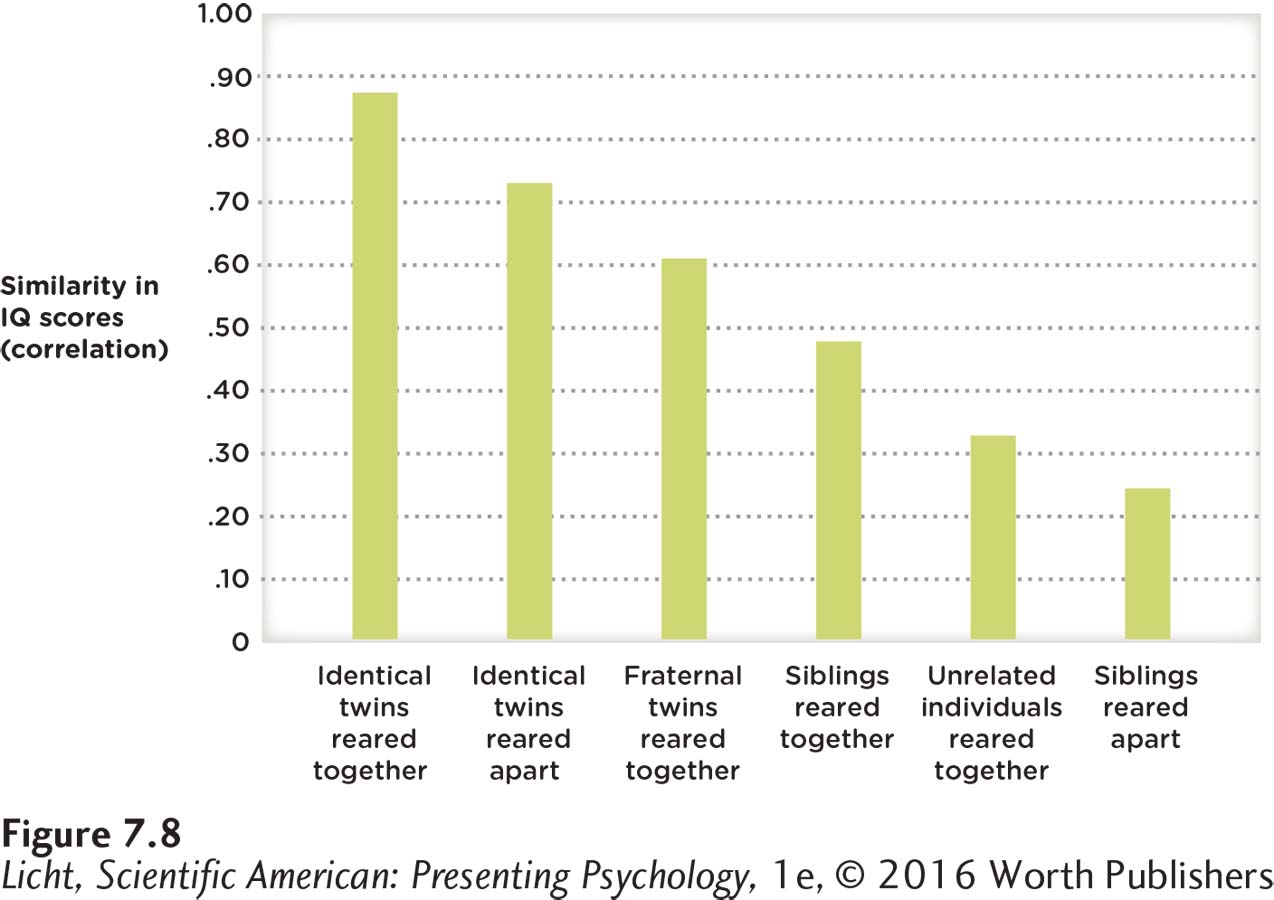

Origins of Intelligence

The most genetically similar people, identical twins, have the strongest correlation between their scores on IQ tests. This suggests that genes play a major role in determining intelligence. But if identical twins are raised in different environments, the correlation is slightly lower, showing some environmental effect (McGue et al., 1993).

Now let’s examine how nature and nurture impact intelligence in general. Twin studies (research involving identical and fraternal twins) are an excellent way to evaluate the relative weights of nature and nurture for virtually any psychological trait. The Minnesota twin studies (Johnson & Bouchard, 2011; McGue, Bouchard, Iacono, & Lykken, 1993) indicate there are strong correlations between the IQ scores of identical twins—

heritability The degree to which hereditary factors (genes) are responsible for a particular characteristic observed within a population; the proportion of variation in a characteristic attributed to genetic factors.

Heritability refers to the degree to which heredity is responsible for a particular characteristic or trait. As psychologists study the individual differences associated with a variety of traits, they try to determine the heritability of each one. Many traits have a high degree of heritability (for example, eye color, height, and other physical characteristics), but others are determined by the environments in which we are raised (for example, manners; Dickens & Flynn, 2001). Results from twin and adoption studies suggest that heritability for “general cognitive abilities” is about 50% (Plomin & DeFries, 1998; Plomin, DeFries, Knopik, & Niederhiser, 2013). In other words, about half of the variation in intellectual or cognitive ability can be attributed to genetic make-

It is important to emphasize that heritability applies to groups of people, not individuals. We cannot say, for example, that an individual’s intelligence level is 40% due to genes and 60% the result of environment. We can only make general predictions about groups and how they are influenced by genetic factors (Dickens & Flynn, 2001).

So where does gender figure into the intelligence equation? Despite differences in brain size and structure, males and females do not differ significantly in terms of general intelligence (Burgaleta et al., 2012; Halpern et al., 2007). Many researchers find this pairing remarkable: “Apparently, males and females can achieve similar levels of overall intellectual performance by using differently structured brains in different ways” (Deary, Penke, & Johnson, 2010, p. 209). Although researchers do find different patterns of neurological activity in males and females, these differences are not necessarily due to nature. The brain can change in response to experience (nurture), and sex differences may be due to changes in synaptic connections and neural networks that result from experiences of being male or female (Hyde, 2007).

We have now explored the various approaches to assessing and conceptualizing intelligence. Let’s shift our focus to a quality that is associated with intelligence but far more difficult to measure: creativity.

Creativity

LO 12 Define creativity and its associated characteristics.

creativity In problem solving, the ability to construct valuable results in innovative ways; the ability to generate original ideas.

Do you remember the last time you encountered a situation or problem that required you to “put on your thinking cap?” Sometimes it takes a little creativity to solve a problem. In a problem-

CHARACTERISTICS OF CREATIVITY Because creativity doesn’t present itself in a singular or uniform manner, it is difficult to measure. Most psychologists agree that there are several basic characteristics associated with creativity (Baer, 1993; Sternberg, 2006a, 2006b):

Originality: the ability to come up with unique solutions when trying to solve a problem

Fluency: the ability to create many potential solutions

Flexibility: the ability to use a variety of problem-

solving tactics to arrive at solutions Knowledge: a sufficient base of ideas and information

Thinking: the ability to see things in new ways, make connections, see patterns

Personality: characteristics of a risk taker, someone who perseveres and tolerates ambiguity

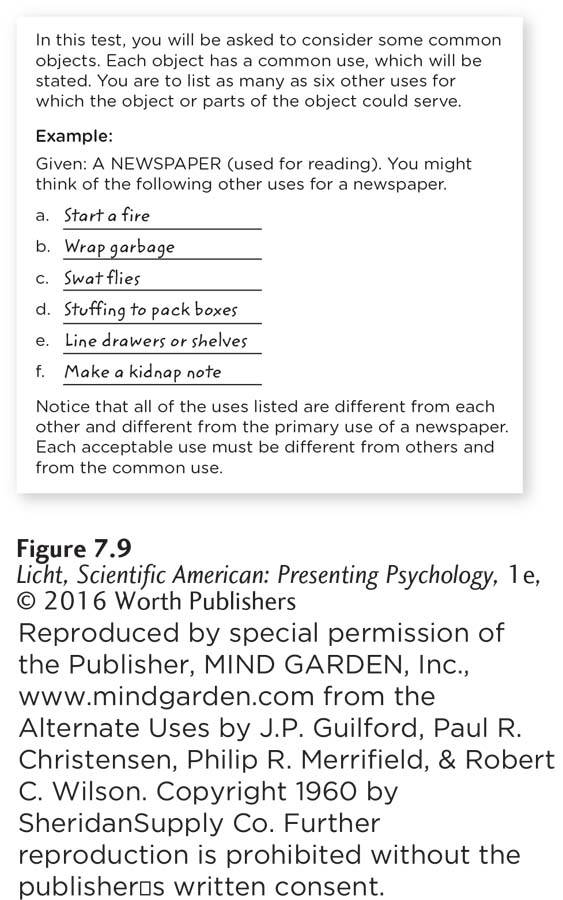

Instructions for Guilford’s Alternate Uses Task

Instructions for Guilford’s Alternate Uses Task

The sample question at right is from Guilford’s Alternate Uses Task, a revised version of the unusual uses test, which is designed to gauge creativity.Reproduced by special permission of the Publisher, MIND GARDEN, Inc., www.mindgarden.com from the Alternate Uses by J.P. Guilford, Paul R. Christensen, Philip R. Merrifield, & Robert C. Wilson. Copyright 1960 by SheridanSupply Co. Further reproduction is prohibited without the publisher’s written consent.Intrinsic motivation: influenced by internal rewards, motivated by the pleasure and challenge of work

divergent thinking The ability to devise many solutions to a problem; a component of creativity.

DIVERGENT AND CONVERGENT THINKING Divergent thinking is an important component of creativity. It refers to the ability to devise many solutions to a problem (Baer, 1993). A classic measure of divergent thinking is the unusual uses test (Guilford, 1967; Guilford, Christensen, Merrifield, & Wilson, 1960; Figure 7.9). A typical prompt would ask the test taker to come up with as many uses for a brick as she can imagine. (What ideas do you have? Paperweight? Shot put? Stepstool?) Remember that we often have difficulty thinking about how to use familiar objects in atypical ways because of functional fixedness.

convergent thinking A conventional approach to problem solving that focuses on finding a single best solution to a problem by using previous experience and knowledge.

In contrast to divergent thinking, convergent thinking focuses on finding a single best solution by converging on the correct answer. Here, we fall back on previous experience and knowledge. This conventional approach to problem solving leads to one solution, but, as we have noted, many problems have multiple solutions.

Creativity comes with many benefits. People with this ability tend to have a broader range of knowledge and interests. They are open to new experiences and often are less inhibited in their thoughts and behaviors (Feist, 2004; Simonton, 2000). The good news is that we can become more creative by practicing divergent thinking, taking risks, and looking for unusual connections between ideas (Baer, 1993).

Sometimes finding those new connections takes a little relaxing on the part of the brain. Let’s see how this phenomenon might come into play by peering into the brain of a rapper.

didn’t SEE that coming

Inside the Brain of a Rapper

Generating rap lyrics on the spot appears to involve a slowdown of activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), a part of the brain thought to play a role in deciding which intentions are transformed into actions (Liu et al., 2012). This loosening of inhibition may facilitate creative expression.

How long would it take you to come up with a rhyme that looks something like this?

How long would it take you to come up with a rhyme that looks something like this?

I shine and glow, even in the dark,

Stay smart, stay sharp, as a harp,

Played by a musician in this position,

Feel blessed to make the whole world listen,

And just glisten without even trying

Even when I die, I won’t stay dead,

And it’s straight off the head,

And it’s straight out the lungs,

Looking fly, fresh, old man, so young

(Mos Def, 2011, February 28)

Hip-

MOS DEFINITELY CREATIVE!

Researchers have studied the brains of freestyle rappers as they “flow,” or “spit rhymes,” and they have discovered an interesting pattern of excitement and calmness in different areas of the brain. Using fMRI, Siyuan Liu and colleagues (2012) compared the brain activity of rappers as they freestyled and performed lyrics they had rehearsed. Freestyle sessions were correlated with greater activity in language-

DR. JILL’S NEWFOUND INTELLIGENCE It took Dr. Jill 8 years to recuperate from what she now calls her “stroke of insight,” and it was not smooth sailing. Regaining her physical and cognitive strength required steadfast determination and painstaking effort. “Recovery was a decision I had to make a million times a day,” she writes (Taylor, 2006, p. 115). She also had many people cheering her on—

DR. JILL’S NEWFOUND INTELLIGENCE It took Dr. Jill 8 years to recuperate from what she now calls her “stroke of insight,” and it was not smooth sailing. Regaining her physical and cognitive strength required steadfast determination and painstaking effort. “Recovery was a decision I had to make a million times a day,” she writes (Taylor, 2006, p. 115). She also had many people cheering her on—

If stroke victims fail to regain all faculties by 6 months, they never will. At least that is what Dr. Jill remembers hearing her doctors say. But she proved all the naysayers wrong. Within 2 years, Dr. Jill was living back in her home state of Indiana and teaching college courses in anatomy/physiology and neuroscience. Four years after the operation, she had retrained her body to walk gracefully and her brain to multitask. By Year 5, she could solve math problems, and by Year 7, she had accepted another teaching position, this time at Indiana University (Taylor, 2006).

Dr. Jill currently serves as the national spokesperson for the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center, where scientists conduct research on brain tissue from cadavers. It took 8 years for Dr. Jill to recover from her stroke. Her bestselling book My Stroke of Insight is being adapted for the big screen by Sony Pictures and Imagine Entertainment (drjilltaylor.com, 2010; IMDB, 2015).

Today, Dr. Jill is working on various projects to increase awareness and understanding of the brain, overseeing her nonprofit organization Jill Bolte Taylor BRAINS, and collaborating with the HAWN Foundation to create a high school curriculum, among other things (drjilltaylor.com, 2010). Dr. Jill finds she has become more open to new experiences and ways of thinking (a prerequisite for creativity), and that she has emerged from her ordeal more empathetic and emotionally aware.

show what you know

Question 1

1. Sternberg believed that intelligence is made up of three types of competencies, including:

linguistic, spatial, musical.

intrapersonal, interpersonal, existential.

analytic, creative, practical.

achievement, triarchic, prototype.

c. analytic, creative, practical.

Question 2

2. Some tests of intelligence measure _________, or a person’s potential for learning, and other tests measure _________, or acquired knowledge.

aptitude; achievement

Question 3

3. Define IQ. How is it derived?

The intelligence quotient (IQ) is a score from an intelligence assessment; it provides a way to compare levels of intelligence across ages. Originally, an IQ score was derived by dividing mental age by chronological age and multiplying that number by 100. Modern intelligence tests still assign a numerical score, although they no longer use the actual quotient score.

Question 4

4. An artist friend of yours easily comes up with unique solutions when trying to solve problems. This _________ is one of the defining characteristics of creativity.

originality