8.5 Adulthood

A WORK IN PROGRESS At the very beginning of this chapter, we introduced Chloe Ojeah, a 22-

A WORK IN PROGRESS At the very beginning of this chapter, we introduced Chloe Ojeah, a 22-

Chloe’s grandfather, J. M. Richard, enjoys breakfast with his wife of six decades. Mr. Richard says that his greatest accomplishment was marrying Mrs. Richard, whom he still loves deeply. Mrs. Richard struggles with Alzheimer’s disease, but her impaired memory does not stop her from enjoying many daily activities.

Like many young adults, Chloe is also beginning to explore her capacity to form deep and loving relationships. Her first serious romantic relationship evolved out of a close friendship she had established while living in Houston. Chloe trusted this boyfriend; she was committed to him; she even loved him, though she wouldn’t say she was “in love” with him. “More than anything,” Chloe insists, “we just enjoyed being around each other.” But spending time together was not much of an option when Chloe relocated to Austin to care for her grandparents. Since they parted ways, Chloe has remained on good terms with her ex-

As Chloe is just beginning to experience her first meaningful relationships, her grandfather, J. M. Richard, is enjoying his 61st year of married life. When you ask Mr. Richard what he considers his most important achievements, the first thing he says is “marrying my wife.” The last few years have been trying, given her battle with Alzheimer’s disease, but Mr. Richard continues to be deeply committed to her. As he himself offers, “We still love each other.”

Looking back on nearly nine decades of life, Mr. Richard says he feels satisfied: “I am happy with my life, and I am happy with my accomplishments.” His fulfillment does not just stem from marriage and fatherhood. “I am also deep into the Baptist church,” Mr. Richard notes. “The other thing I have been blessed with up until a year ago was good health.” Before the stroke, Mr. Richard was able to drive his car, which allowed him the freedom to take care of business at his funeral home, maintain the various buildings he rents out to tenants, and oversee building projects on his properties. Now he has nerve damage on the left side of his body, which causes persistent pain. He walks with a cane, is visually impaired, and can no longer drive.

But Mr. Richard hasn’t thrown in the towel. With the help of an occupational therapist, he hopes to get behind the wheel again one day. And unlike many people, even those who are half his age, he spends 30 to 40 minutes pedaling on his exercise bike each day. Mr. Richard also maintains a vibrant intellectual life, and he continues to talk on the phone with his employees at the funeral home several times a day.

Whatever you want from life, you are most likely to pursue and attain it during the developmental stage known as adulthood. Developmental psychologists have identified various stages of this long period, each corresponding to an approximate age group: early adulthood spans the twenties and thirties, middle adulthood the forties to mid-

Physical Development

LO 17 Name some of the physical changes that occur across adulthood.

The most obvious signs of aging tend to be physical in nature. Often you can estimate a person’s age just by looking at his hands or facial lines. Let’s get a sense of some of the basic body changes that occur through adulthood.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we described causes for hearing impairment. Damage to the hair cells or the auditory nerve is called sensorineural deafness. Conduction hearing impairment results from damage to the eardrum or the middle-

EARLY ADULTHOOD During early adulthood, our sensory systems are sharp, and we are at the height of our muscular and cardiovascular ability. But some systems have already begun their downhill journey. Hearing, for instance, often starts to decline as a result of noise-

As we head toward our late thirties, fertility-

Exercise is one of the best ways to fight the aging process. Working out on a regular basis improves cardiovascular health, bone and muscle strength, and mood. A study of more than 400,000 people in Taiwan found that those who exercised just 15 minutes a day lived an average of 3 years longer than their sedentary peers (Wen et al., 2011).

MIDDLE ADULTHOOD In middle adulthood, the skin wrinkles and sags due to loss of collagen and elastin, and skin spots may appear (Bulpitt, Markowe, & Shipley, 2001). Hair starts to turn gray and may fall out. Hearing loss continues and may be exacerbated by exposure to loud noises (Kujawa & Liberman, 2006). Eyesight may decline. The bones weaken. Oh, and did we mention you might shrink? But do not despair. There are measures you can take to slow the aging process. For example, genes influence height and bone mass, but research suggests we can limit the shrinking process through continued exercise. In one study, researchers followed over 2,000 people for three decades. Everyone in the study got shorter (the average height loss being 4 centimeters, or about 1.6 inches), but those who had engaged in “moderate vigorous aerobic” exercise lost significantly less (Sagiv, Vogelaere, Soudry, & Ehrsam, 2000). To maintain your stature and overall physique, you would be wise to participate in lifelong moderate endurance activities such as jogging, walking, and swimming.

menopause The time when a woman no longer ovulates, her menstrual cycle stops, and she is no longer capable of reproduction.

For women, middle adulthood is a time of major physical change. Estrogen production decreases, the uterus shrinks, and menstruation no longer follows a regular pattern. This marks the transition toward menopause, the time when ovulation and menstruation cease, and reproduction is no longer possible. Menopausal women can experience hot flashes, sweating, vaginal dryness, and breast tenderness (Newton et al., 2006). These symptoms may sound unpleasant, but many women consider menopause to be a temporary inconvenience, reporting a sense of relief following the cessation of their menstrual periods, as well as increased interest in sexual activity (Etaugh, 2008).

Men experience their own constellation of midlife physical changes, sometimes referred to as male menopause or andropause. Some suggest calling it androgen decline, as there is a reduction in testosterone production, not an end to it (Morales, Heaton, & Carson, 2000). Men in middle adulthood may complain of depression, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties, which might be associated with lower testosterone. But research suggests this link between hormones and behavior is evident in only a tiny proportion of aging men (Pines, 2011).

LATE ADULTHOOD Late adulthood, which begins around 65, is also characterized by the decline of many physical and psychological functions. Eye problems, such as cataracts and impaired night vision, are common. Hearing continues on a downhill course, and reaction time increases (Fozard, 1990). The brain processes information more slowly, and brain regions responsible for memory deteriorate (Eckert, Keren, Roberts, Calhoun, & Harris, 2010).

Apply This

Move It or Lose It

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we reported that studies with nonhuman animals and humans have shown that some areas of the brain are constantly generating new neurons, in a process known as neurogenesis. As we age, this production of new neurons seems to be supported by physical exercise.

Some physical decline is inevitable with age, but it is possible to grow old gracefully. One of the best ways to fight aging is to get your body moving. Aerobic exercise improves bone density and muscle strength, and lowers the risk for cardiovascular disease and obesity. It’s good for your brain too. “A single bout of moderate [aerobic] exercise” seems to provide a short-

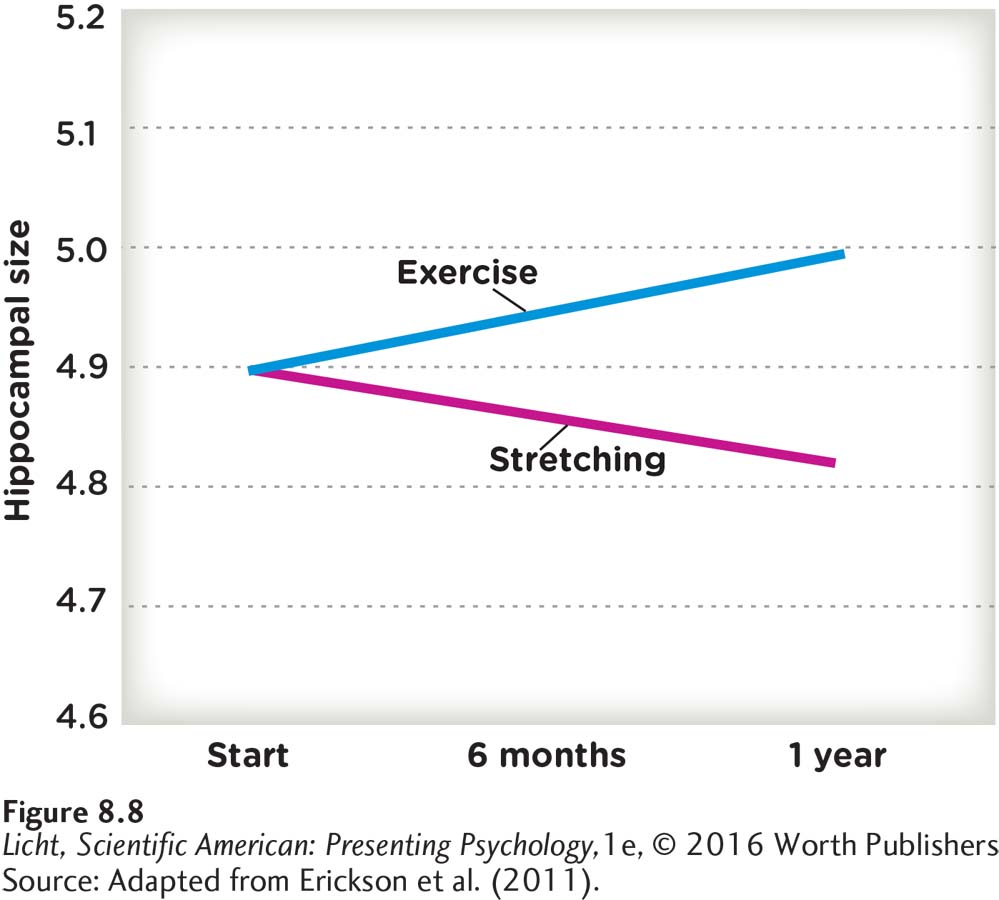

Researchers interested in the effects of exercise on the aging brain randomly assigned participants to two groups: One group engaged in a program of gentle stretching exercises, and the other began doing more aerobic activity. During the course of the yearlong study, the researchers found typical levels of age-

Cognitive Development

What’s going on in the brain as we pass through the various stages of adulthood, and how do these changes affect our ability to function? Let’s explore cognitive development in adulthood.

LO 18 Identify some of the cognitive changes that occur across adulthood.

EARLY ADULTHOOD Measures of aptitude, such as intelligence tests, indicate that cognitive ability remains stable from early to middle adulthood (Larsen, Hartmann, & Nyborg, 2008), though processing speed begins to decline (Schaie, 1993). Young adults are theoretically in Piaget’s formal operational stage, which means they can think logically and systematically, but some researchers estimate that only 50% of adults ever exhibit formal operational thinking (Arlin, 1975).

MIDDLE AND LATE ADULTHOOD Much of the discussion of middle adulthood has focused on decline: declining skin elasticity, testosterone, cardiovascular health, and so on. Yet cognitive function does not necessarily decrease during middle adulthood. Longitudinal studies by Schaie and colleagues indicate that decreases in cognitive abilities cannot be reliably measured before 60 (Gerstorf, Ram, Hoppmann, Willis, & Schaie, 2011; Schaie, 1993, 2008). There are some exceptions, however. Midlife is a time when information processing and memory can decline, particularly the ability to remember past events (Ren, Wu, Chan, & Yan, 2013).

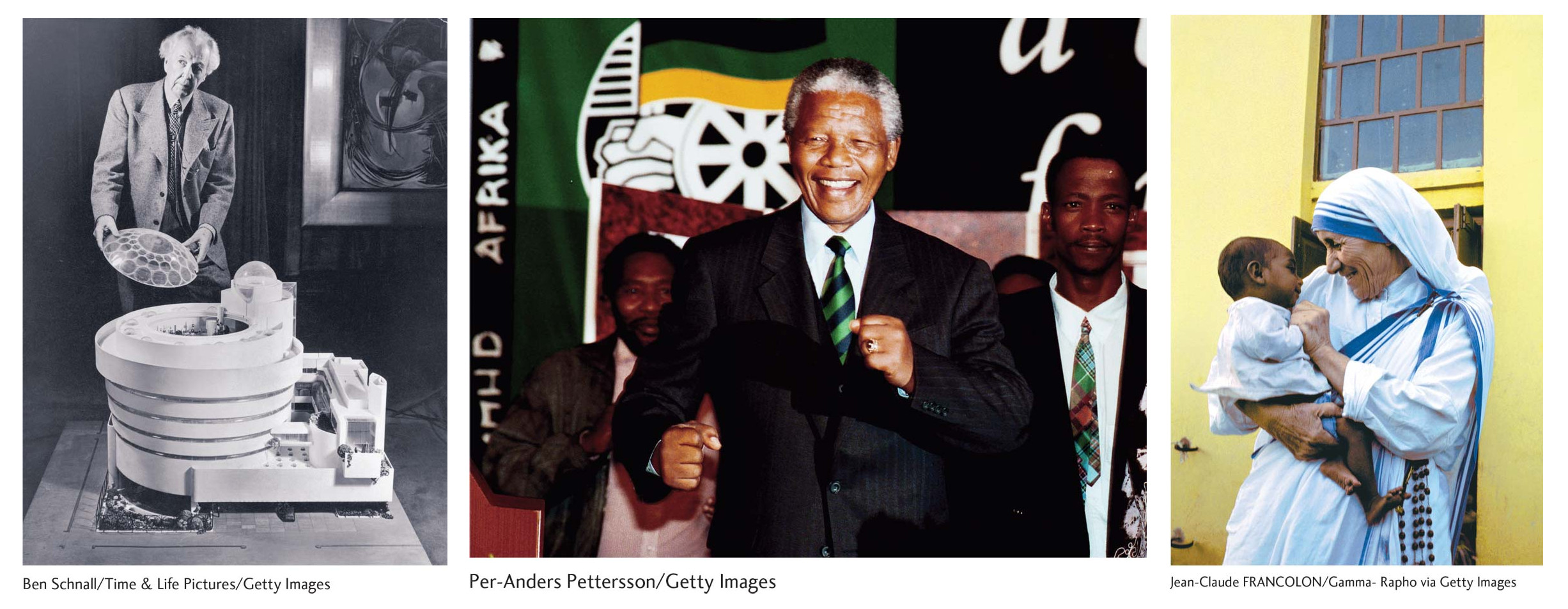

Old age can be a time of great artistic, intellectual, and humanitarian achievement. Frank Lloyd Wright (left) was 89 when he completed the design for New York’s Guggenheim Museum; Nelson Mandela (middle) was 76 when he became the first Black president of South Africa; and Mother Teresa (right) was 69 when she received the Nobel Peace Prize.

After the age of 70, cognitive decline is more apparent. The Seattle Longitudinal Study has shown that the cognitive performance of today’s 70-

Some types of cognitive skills diminish in old age and others become more refined. Older people may not remember all of their academic knowledge, but their practical abilities seem to grow. Life experiences allow people to develop a more balanced understanding of the world around them, one that only comes with age (Sternberg & Grigorenko, 2005).

crystallized intelligence Knowledge gained through learning and experience.

fluid intelligence The ability to think in the abstract and create associations among concepts.

When studying cognitive changes across the life span, psychologists frequently describe two types of intelligence: crystallized intelligence, the knowledge we gain through learning and experience, and fluid intelligence, the ability to think in the abstract and create associations among concepts. As we age, the speed with which we acquire new material and create associations decreases (von Stumm & Deary, 2012). In one study, researchers examined performance on fluid and crystallized intelligence tasks in adults between the ages of 20 and 78. Crystallized abilities increased with age, whereas fluid abilities increased from 20 to 30 years of age and remained stable until age 50 (Cornelius & Caspi, 1987). Working memory, the active processing component of short-

CONNECTIONS

Here, we are reminded of an issue presented in Chapter 1: We must be careful not to equate correlation with causation. In this case, if you experience a decline in cognitive ability, you are less likely to work. Thus, it is the cognitive decline that would lead to the lack of work.

Earlier we mentioned that physical exercise provides a cognitive boost. The same appears to be true of mental exercises, such as those required for playing a musical instrument (Hanna-

Socioemotional Development

Socioemotional development does not always occur in a neat, stepwise fashion. Some of us become parents as teenagers, others not until our forties. This next section describes a host of social and emotional transformations that typically occur during adulthood.

LO 19 Explain some of the socioemotional changes that occur across adulthood.

ERIKSON AND ADULTHOOD Earlier we described Erikson’s approach to explaining socioemotional development from infancy through adolescence, noting that unsuccessful resolution of prior stages has implications for the stages that follow (see Table 8.3). During young adulthood (twenties to forties), people are challenged by intimacy versus isolation. Young adults tend to focus on creating meaningful, deep relationships, and failing at this endeavor may lead to a life of isolation. Erikson also believed that we are unable to form these relationships if identity has not been clearly established in the identity versus role confusion of adolescence.

Moving into middle adulthood (forties to mid-

In late adulthood, we look back on life and evaluate how we have done, a crisis of integrity versus despair (mid-

Before we further explore socioemotional development in adulthood, we must note that Erikson’s theory, though very important in the field of developmental psychology, has provided more framework than substantive research findings. His theory was based on case studies, with limited supporting research. In addition, the developmental tasks of Erikson’s stages might not be limited to the particular time frame proposed. For example, creating an adult identity is not limited to adolescence, as this stage may resurface at any point in adulthood (Schwartz, 2001).

ROMANCE AND RELATIONSHIPS Young adulthood is a time when romantic relationships move in a new direction. The focus shifts away from fun-

PARENTING Do you ever find yourself watching parent-

authoritarian parenting A rigid parenting style characterized by strict rules and poor communication skills.

Parents who insist on rigid boundaries, show little warmth, and expect high control exhibit authoritarian parenting. They want things done in a certain way, no questions asked. “Because I said so” is a common justification used by such parents. Authoritarian parents are extremely strict and demonstrate poor communication skills with their children. Their kids, in turn, tend to have lower self-

authoritative parenting A parenting style characterized by high expectations, strong support, and respect for children.

Authoritative parenting may sound similar to authoritarian parenting, but it is very different. Parents who practice authoritative parenting set high expectations, demonstrate a warm attitude, and are responsive to their children’s needs. Being supported and respected, children of authoritative parents are quite responsive to their parents’ expectations. They also tend to be self-

permissive parenting A parenting style characterized by low demands of children and few limitations.

With permissive parenting, the parent demands little of the child and imposes few limitations. These parents are very warm but often make next to no effort to control their children. Ultimately, their children tend to lack self-

uninvolved parenting A parenting style characterized by a parent’s indifference to a child, including a lack of emotional involvement.

Uninvolved parenting describes parents who seem indifferent to their children. Emotionally detached, these parents exhibit minimal warmth and devote little time to their children, although they do provide for their children’s basic needs. Children raised by uninvolved parents tend to exhibit behavioral problems, poor academic performance, and immaturity (Baumrind, 1991).

Keep in mind that the great majority of research on these parenting styles has been conducted in the United States, which should make us wonder how applicable these categories are in other countries and cultures (Grusec, Goodnow, & Kuczynski, 2000). Additional factors to consider include the home environment, the child’s personality and development, and the unique parent–

GROWING OLD WITH GRACE When many people think of growing older, they imagine a frail old woman (or man) sitting in a bathrobe and staring out the window, unable to care for herself. This stereotype is not accurate. As of 2000, fewer than 5% of Americans older than 65 lived in a nursing home (Hetzel & Smith, 2001). Most older adults in the United States enjoy active, healthy, independent lives. They are involved in their communities, faiths, and social lives, and contrary to popular belief—

Older people might feel happy because they no longer care about proving themselves in the world, they are pleased with the outcome of their lives, or they have developed a strong sense of emotional equilibrium (Jeste et al., 2012). Research suggests that older adults who are healthy, independent, and engaged in social activities also report being happy, and there is some evidence that this increased happiness may result in a longer life (Oerlemans, Bakker, & Veenhoven, 2011). Americans are now living longer than ever, with the average life expectancy of women being 81.1 years and men 76.3 years (Hoyert & Xu, 2012). Could happiness be one of the factors driving this increase in life span?

Death and Dying

We have spent this entire chapter discussing life. Many of the stages and changes described occur at different times for different people, sometimes overlapping, other times skipped altogether. When it comes to life, nothing is certain—

LO 20 Describe Kübler-

Apart from sex, few topics are as difficult to address as death and dying. Psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-

Denial: In the denial stage, a person may react to the news with shock and disbelief, perhaps even suggesting the doctors are wrong. Unable to accept the diagnosis, he may seek other medical advice.

Anger: A dying person may feel anger toward others who are healthy, or toward the doctor who does not have the cure. Why me? she may wonder, projecting her anger and irritability in a seemingly random fashion.

Bargaining: This stage may involve negotiating with God, doctors, or other powerful figures for a way out. Usually, this involves some sort of time frame: Let me live to see my firstborn get married, or Just give me one more month to get my finances in order.

Depression: There comes a point when a dying person can no longer ignore the inevitable. Depression may be due to the symptoms of the patient’s actual illness, but it can also result from the overwhelming sense of loss—

the loss of the future. Acceptance: Eventually, a dying person accepts the finality of his predicament; death is inevitable, and it is coming soon. This stage can deeply impact family and close friends, who, in some respects, may need more support than the person who is dying. According to one oncologist, the timing of acceptance is quite variable. For some people, it occurs in the final moments before death; for others, soon after they learn there is no chance of recovery from their illness (Lyckholm, 2004).

Kübler-

across the WORLD

Death in Different Cultures

What does death mean to you? Some of us believe death marks the beginning of a peaceful afterlife. Others see it as a crossing over from one life to another. Still others believe death is like turning off the lights; once you’re gone, it’s all over.

What does death mean to you? Some of us believe death marks the beginning of a peaceful afterlife. Others see it as a crossing over from one life to another. Still others believe death is like turning off the lights; once you’re gone, it’s all over.

Views of death are very much related to religion and culture. A common belief among Indian Hindus, for example, is that one should spend a lifetime preparing for a “good death” (su-

EVERY CULTURE HAS ITS OWN IDEAS ABOUT DEATH.

In Japan and other parts of East Asia, families often make medical decisions for the dying person (Matsumura et al., 2002). They may avoid using words like “cancer” to shield them from the bad news, believing this knowledge may cause them to lose hope and deteriorate further (Koenig & Gates-

Interesting as these findings may be, remember they are only cultural trends. Like any developmental step, the experience of death is shaped by countless social, psychological, and biological factors.

A mariachi band plays at a cemetery in Mexico’s Michoacan state on Dia de los Muertos, “Day of the Dead.” During this holiday, people in Mexico and other parts of Latin America celebrate the lives of the deceased. Music is played, feasts are prepared, and graves are adorned with flowers to welcome back the spirits of relatives who have passed. In this cultural context, death is not something to be feared or dreaded, but rather a part of life that is embraced (National Geographic, 2015).

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS Do you wonder what became of Jasmine Mitchell and Chloe Ojeah? Both women continue to stay busy, pursuing careers and looking after their families. Chloe is still studying hard and caring for her grandparents. Jasmine graduated from Waubonsee Community College, went on to study social work at Aurora University, and is now earning her Master’s degree in social work at Aurora. Eddie is busy practicing baseball and mixed martial arts, while Jocelyn juggles her honors classes with college preparation and church youth group activities.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS Do you wonder what became of Jasmine Mitchell and Chloe Ojeah? Both women continue to stay busy, pursuing careers and looking after their families. Chloe is still studying hard and caring for her grandparents. Jasmine graduated from Waubonsee Community College, went on to study social work at Aurora University, and is now earning her Master’s degree in social work at Aurora. Eddie is busy practicing baseball and mixed martial arts, while Jocelyn juggles her honors classes with college preparation and church youth group activities.

show what you know

Question 1

1. Physical changes during middle adulthood include declines in hearing, eyesight, and height. Research suggests which of the following can help limit the shrinking process?

physical exercise

elastin

andropause

collagen

a. physical exercise

Question 2

2. As we age, our _________ intelligence, or ability to think abstractly, decreases, but our knowledge gained through experience, our _________ intelligence, increases.

fluid; crystallized

Question 3

3. When faced with death, a person can go through five stages. The final stage is _________, and sometimes family members need more support during this stage than the dying person.

denial

anger

bargaining

acceptance

d. acceptance

Question 4

4. An aging relative in his mid-

integrity; despair