9.3 Sexual Motivation

sexuality Sexual activities, attitudes, and behaviors.

It’s obvious we need food, water, and sleep to survive. But where does sex fit into the needs hierarchy? “Sex may be studied as a purely physiological need,” according to Maslow, “[but] ordinarily sexual behavior is multi-

The Birds and the Bees

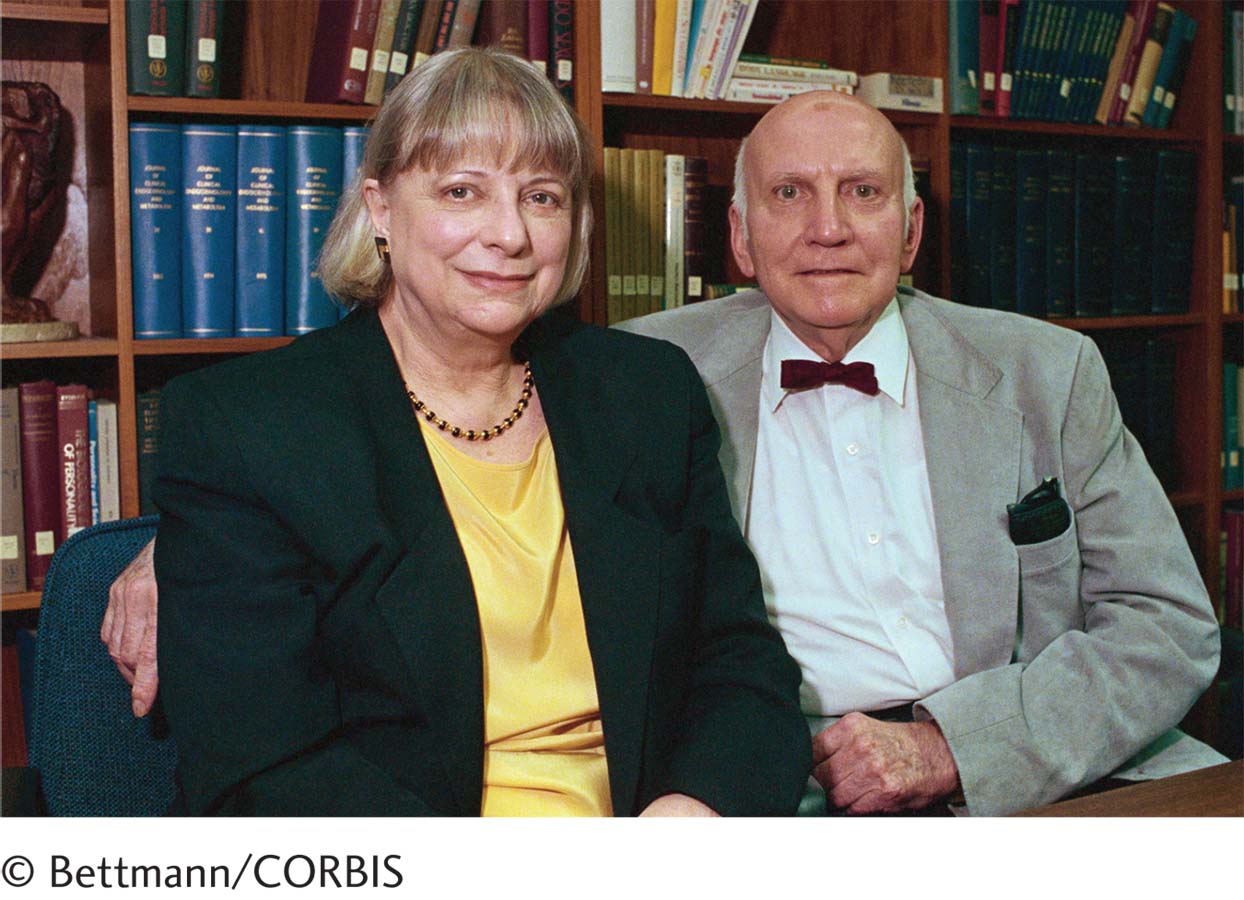

To grasp the complexity of human sexuality, we must understand the basic physiology of the sexual response. Enter William Masters and Virginia Johnson and their pioneering laboratory research, which included the study of approximately 10,000 distinct sexual responses of 312 male and 382 female participants (Masters & Johnson, 1966).

LO 9 Describe the human sexual response as identified by Masters and Johnson.

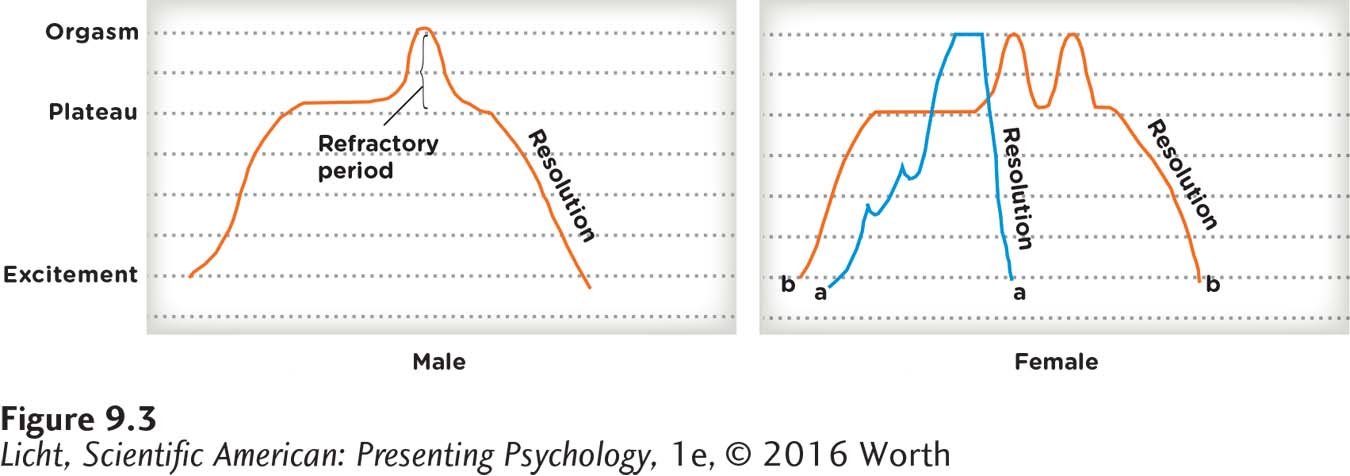

HUMAN SEXUAL RESPONSE CYCLE Masters and Johnson began their research in 1954, not exactly a time when sex was thought to be an acceptable subject for dinner conversation. Nevertheless, almost 700 people volunteered to participate in their study, which lasted a little more than a decade (Masters & Johnson, 1966). Using a variety of instruments to measure blood flow, body temperature, muscular changes, and heart rate, they discovered that most people experience a similar physiological sexual response, which can result from oral stimulation, manual stimulation, vaginal intercourse, or masturbation. Men and women tend to follow a similar pattern or cycle: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution (Figure 9.3). These phases vary in duration for different people.

376

In the male sexual response (left), excitement is typically followed by a brief plateau, orgasm, and then a refractory period during which another orgasm is not possible. In the female sexual response (right), there is no refractory period. Orgasm is typically followed by resolution (a) or, if sexual stimulation continues, additional orgasms (b).

In the mid-

Sexual arousal begins during the excitement phase. This is when physical changes start to become evident. Muscles tense, the heartbeat quickens, breathing accelerates, the nipples become firm, and blood pressure rises a bit. In men, the penis becomes erect, the scrotum constricts, and the testes pull up toward the body. In women, the vagina lubricates and the clitoris swells (Levin, 2008).

Next is the plateau phase. There are no clear physiological signs to mark the beginning of the plateau, but it is the natural progression from the excitement phase. During the plateau phase, the muscles continue to tense, breathing and heart rate increase, and the genitals begin to change color as blood fills the area. This phase is usually quite short-

orgasm A powerful combination of extremely gratifying sensations and a series of rhythmic muscular contractions.

The shortest phase of the sexual response cycle is the orgasm phase. As the peak of sexual response is reached, an orgasm occurs, which is a powerful combination of extremely gratifying sensations and a series of rhythmic muscular contractions. When men and women are asked to describe their orgasmic experiences, it is very difficult to differentiate between them. Brain activity observed via PET scans is also quite similar (Georgiadis, Reinders, Paans, Renken, & Kortekaas, 2009; Mah & Binik, 2001).

refractory period An interval of time during which a man cannot attain another orgasm.

The final phase of the sexual response cycle, according to Masters and Johnson, is the resolution phase. This is when bodies return to a relaxed state. Without further sexual arousal, the blood flows out of the genitals, and blood pressure, heart rate, and breathing return to normal. Men lose their erection, the testes move down, and the skin of the scrotum loosens. Men will also experience a refractory period, an interval during which they cannot attain another orgasm. This can last from minutes to hours, and typically the older a man is, the longer the refractory period lasts. For women, the resolution phase is characterized by a decrease in clitoral swelling and a return to the normal labia color. Women do not experience a refractory period, and if sexual stimulation continues, some are capable of having multiple orgasms.

Masters and Johnson’s landmark research has led to further studies of the physiological aspects of the sexual response cycle, and although their basic model is viewed as valid, research suggests there may be the need for “correction or modification, or additional explanation” (Levin, 2008, p. 2). As mentioned, sex is different for every person, and not everyone fits neatly into the same model. This idea applies not only to the physical experience of sex, but to all aspects of sexuality, including sexual orientation.

Sexual Orientation

377

LO 10 Define sexual orientation and summarize how it develops.

sexual orientation A person’s enduring sexual interest in individuals of the same sex, opposite sex, or both sexes.

heterosexual Attraction to members of the opposite sex.

homosexual Attraction to members of the same sex.

bisexual Attraction to members of both the same and opposite sex.

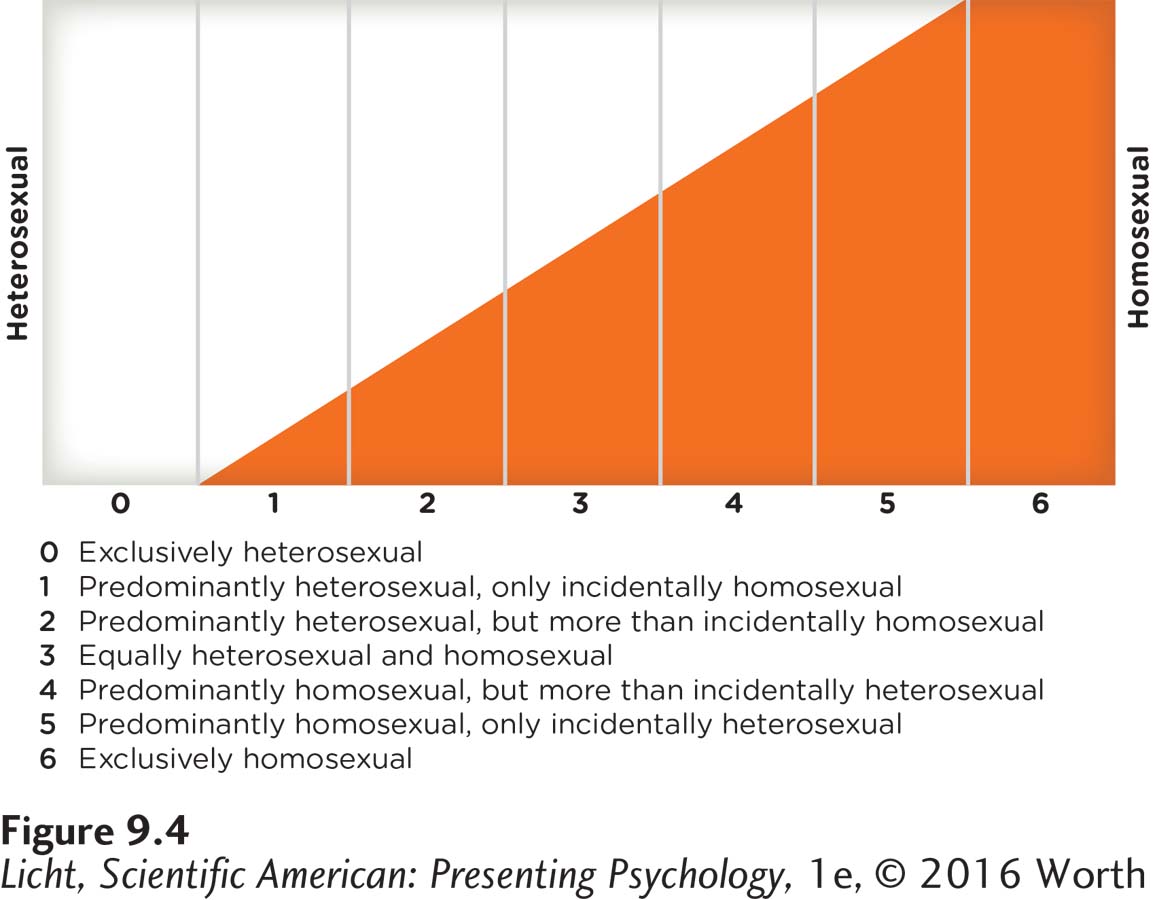

When interviewing people for a study on human sexuality, Alfred Kinsey and his colleagues (1948) discovered that people were not always exclusively heterosexual or homosexual. Instead, some described thoughts and behaviors that put them somewhere in between. This finding led the Kinsey team to develop the scale below, which shows that sexual orientation lies on a continuum.

Reprinted by permission of the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, Inc.

Sexual orientation is the “enduring pattern” of sexual, romantic, and emotional attraction that individuals exhibit toward the same sex, opposite sex, or both sexes (APA, 2008). When attracted to members of the opposite sex, sexual orientation is heterosexual. When attracted to members of the same sex, sexual orientation is homosexual, commonly referred to as “lesbian” for women and “gay” for men (APA, 2008). When attracted to members of the same sex and members of the opposite sex, sexual orientation is bisexual, although most people tend to prefer one sex or the other. Those who do not feel sexually attracted to others are asexual. Lack of interest in sex does not necessarily prevent a person from maintaining relationships with spouses, partners, or friends, but little is known about the impact of asexuality because research on the topic is scarce.

WHAT’S IN A NUMBER? What percentage of the population is heterosexual? How about homosexual and bisexual? These questions may seem straightforward, but they are not easy to answer, partly because there are no clear-

How Sexual Orientation Develops

We are not sure how sexual orientation develops, although most research supports biological factors. Among professionals in the field, there is near agreement that human sexual orientation is not a matter of choice. Research has focused on everything from genetics to culture, but there is no strong evidence that sexual orientation is determined by one particular factor (or set of factors). Instead, it appears to result from an interaction between nature and nurture, but this is still under investigation, and may never be fully determined or understood (APA, 2008).

GENETICS AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION To determine the influence of biology in sexual orientation, we turn to twin studies, which are commonly used to examine the degree to which nature and nurture contribute to psychological traits. Since monozygotic twins share 100% of their genetic make-

378

Researchers have searched for specific genes that might influence sexual orientation. Some have suggested that genes associated with male homosexuality might be transmitted by the mother. In one key study, around 64% of male siblings who were both homosexual had a set of several hundred genes in common, and these genes were located on the X chromosome (Hamer, Hu, Magnuson, Hu, & Pattatucci, 1993). But critics suggest this research was flawed, and no replications of this “gay gene” finding have been published since the original study (O’Riordan, 2012). Despite numerous attempts to identify genetic markers for homosexuality, researchers have had very little success (Dar-

THE BRAIN AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION Researchers have also studied the brains of people across sexual orientations, and their findings are interesting. Neuroscientist Simon LeVay (1991) discovered that a “small group of neurons” in the hypothalamus of homosexual men was almost twice as big as that found in heterosexual men. He did not suggest this size difference was indicative of homosexuality, but he did find it intriguing. LeVay also noted that these differences could have been the result of factors unrelated to sexual orientation. More recently, researchers using MRI technology found the corpus callosum to be thicker in homosexual men (Witelson et al., 2008).

Comedian Wanda Sykes (left) and her wife, Alex Sykes, were married in 2008, when same-

HORMONES AND SEXUAL ORIENTATION How do such differences arise in the brain? They may emerge before birth; hormones (estrogen and androgens) secreted by the fetal gonads play a role in the development of reproductive anatomy. One hypothesis is that the presence of androgens (the hormones secreted primarily by the male gonads) influences the development of a sexual orientation toward women. This would lead to heterosexual orientation in men, but homosexual orientation in women (Mustanski, Chivers, & Bailey, 2002). Because it would be unethical to manipulate hormone levels in pregnant women, researchers rely on cases in which hormones are elevated because of a genetic abnormality or medication taken by a mother. For example, high levels of androgens early in a pregnancy may cause girls to be more “male-

Interestingly, having older brothers in the family seems to be associated with homosexuality in men (Blanchard, 2008). Why is this so? Evolutionary theory would suggest that the more males there are in a family, the more potential for “unproductive competition” among the male siblings. A homosexual younger brother would present less competition for older brothers in terms of securing mates and resources to support offspring.

BIAS Although differences in sexual orientation are universal and have been evident throughout recorded history, individuals identified as members of the nonheterosexual minority have been subjected to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. Nonheterosexual people in the United States, for example, have been, and continue to be, subjected to harassment, violence, and unfair practices related to housing and employment.

EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY AND SEX What is the purpose of sex? Evolutionary psychology would suggest that humans have sex to make babies and ensure the survival of the species (Buss, 1995). But if this were the only reason, then why would so many people choose same-

379

There are other reasons to believe that there is more to human sex than making babies. If sex were purely for reproduction, we would expect to see sexual activity occurring only during the fertile period of the female cycle. Obviously, this is not the case. People have sex throughout a woman’s monthly cycle and long after she goes through menopause. Sex is for feeling pleasure, expressing affection, and forming social bonds.

The Sex We Have

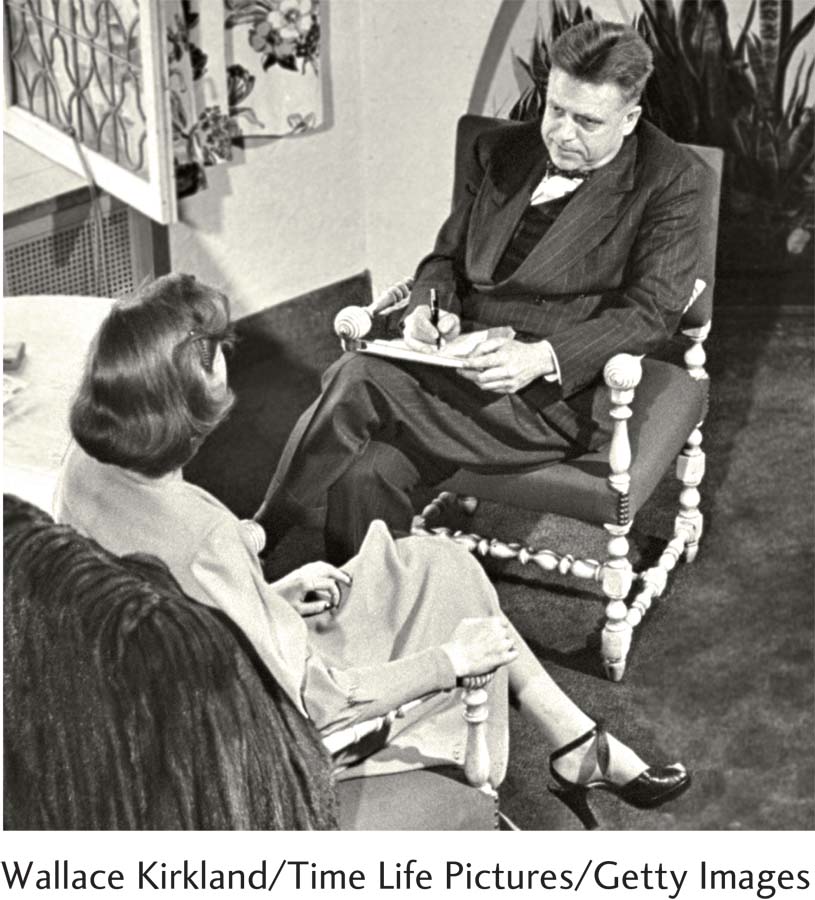

Alfred Kinsey meets with an interview subject in his office at the Institute for Sex Research, now The Kinsey Institute. Kinsey began investigating human sexuality in the 1930s, when talking about sex was taboo. He started gathering data with surveys, but then switched to personal interviews, which he believed to be more effective. These interviews often went on for hours and included hundreds of questions (Public Broadcasting Service [PBS], 2005, January 27).

It is only natural for us to wonder if what we are doing between the sheets (or elsewhere) is typical or healthy. Is it normal to masturbate? Is it normal to fantasize about sex with strangers? The answers to these types of questions depend somewhat on cultural context. Most of us unknowingly learn sexual scripts, or cultural rules that tell us what types of activities are “appropriate” and don’t interfere with healthy sexual intimacy. In some cultures, the sexual script suggests that women should have minimal, if any, sexual experience before marriage, but men are expected to explore their sexuality, or “sow their wild oats.” Of course, not everyone follows the sexual scripts they are assigned.

KINSEY BREAKS GROUND When did researchers begin exploring sexuality in a systematic way? Alfred Kinsey and colleagues were among the first to try to scientifically and objectively examine human sexuality in America (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, & Gebhard, 1953). Using the survey method, Kinsey and his team collected data on the sexual behaviors of 5,300 White males and 5,940 White females. Their findings were surprising; both men and women masturbated, and participants had experiences with premarital sex, adultery, and sexual activity with someone of the same sex. Perhaps more shocking was the fact that so many people were willing to talk about their personal sexual behavior in post–

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we emphasized that representative samples enable us to generalize findings to populations. Here we see that inferences about sexual behaviors for groups other than White, well-

The Kinsey study was groundbreaking in terms of its data content and methodology, which included accuracy checks and assurances of confidentiality. The data have served as a valuable reference for researchers studying how sexual behaviors have evolved over time. However, Kinsey’s work was not without limitations. For example, Kinsey and colleagues (1948, 1953) utilized a biased sampling technique that resulted in a group of participants that was not representative of the population. It was a completely White sample, with an overrepresentation of well-

SEXUAL ACTIVITY IN RELATIONSHIPS Subsequent research has been better designed, using samples that are more representative of the population (Herbenick et al., 2010; Michael, Laumann, Kolata, & Gagnon, 1994). Some of the findings may surprise you, others probably not. Around 77% of adults in the United States report they engaged in intercourse by age 20, regardless of cultural background or ethnicity. By the age of 44, 95% of adults have had intercourse. And the overwhelming majority did not wait for marriage (Finer, 2007). However, married people do have more sex than those who are unmarried (Laumann, Gagnon, Micheal, & Michaels, 1994). According to a large study of Swedish adults, the frequency of penile–

380

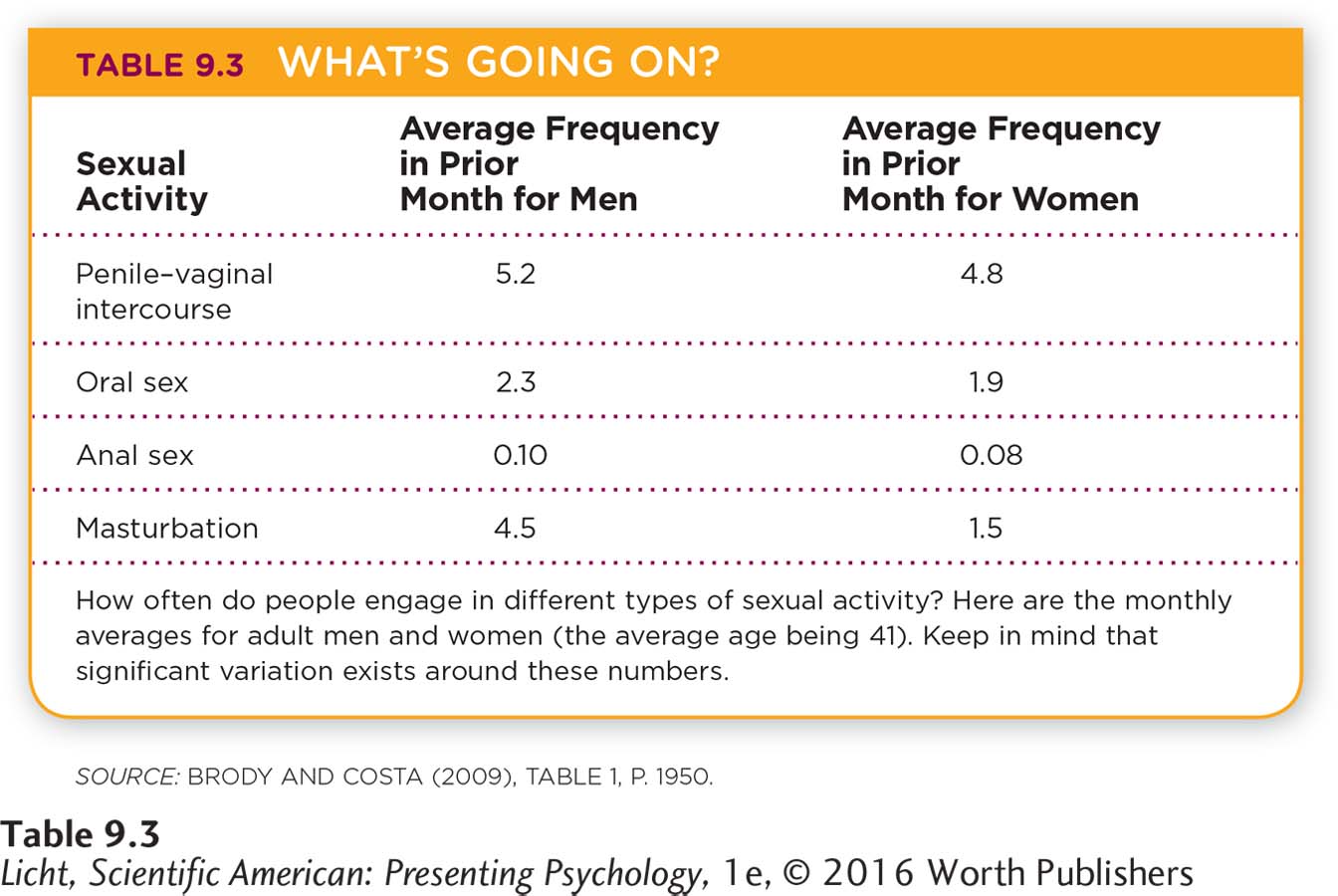

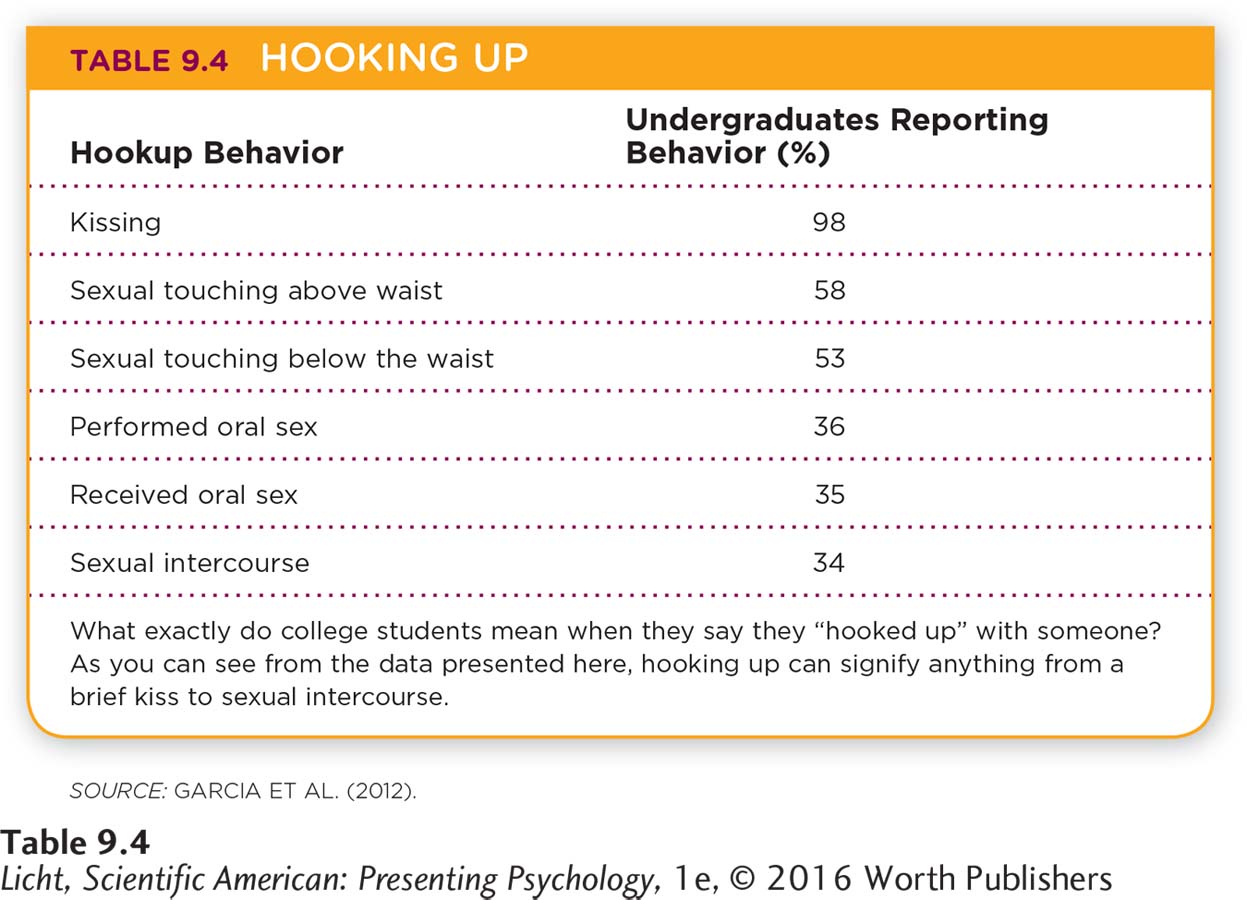

SEXUAL ACTIVITY AND GENDER DIFFERENCES As stereotypes might suggest, men think about sex more often than women (Laumann et al., 1994), and they consistently report a higher frequency of masturbation (Peplau, 2003; see Table 9.3 for reported gender differences in frequency of sexual activity). Men in the United States tend to be more tolerant than women when it comes to casual sex before marriage, as well as more permissive in their attitudes about extramarital sex (Laumann et al., 1994). But these attitude differences are not apparent in heterosexual teenagers and young adults (Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriwether, 2012). For these young people, attitudes about casual sex are apparent in their “hookup” behavior (Table 9.4).

381

THINK again

Sext You Later

What kinds of factors do you think encourage casual attitudes about sex among teens? Most adolescents have cell phones these days (78%, according to one survey; Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, 2013), and a large number of those young people are using their phones to exchange text messages with sexually explicit words or images. In other words, today’s teenagers are doing a lot of sexting. One study found that 20% of high school students have used their cell phones to share sexual pictures of themselves, and twice as many have received such images from others (Strassberg, McKinnon, Sustaíta, & Rullo, 2013). Teens who sext are more likely to have sex and take sexual risks, such as having unprotected sex (Rice et al., 2012).

What kinds of factors do you think encourage casual attitudes about sex among teens? Most adolescents have cell phones these days (78%, according to one survey; Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, 2013), and a large number of those young people are using their phones to exchange text messages with sexually explicit words or images. In other words, today’s teenagers are doing a lot of sexting. One study found that 20% of high school students have used their cell phones to share sexual pictures of themselves, and twice as many have received such images from others (Strassberg, McKinnon, Sustaíta, & Rullo, 2013). Teens who sext are more likely to have sex and take sexual risks, such as having unprotected sex (Rice et al., 2012).

ARE TEENS WHO SEXT MORE LIKELY TO HAVE SEX?

Sexting carries another set of risks for those who are married or in committed relationships. As many people see it, sexting outside a relationship is a genuine form of cheating. And because text messages can be saved and forwarded, it becomes an easy and effective way to damage the reputations of people, sometimes famous ones. Perhaps you have read about the sexting scandals associated with golfer Tiger Woods, ex-

Now that’s a lot of bad news about sexting. But can it also occur in the absence of negative behaviors and outcomes? When sexting is between two consenting, or shall we say “consexting,” adults, it may be completely harmless (provided no infidelity is involved). According to one survey of young adults, sexting was not linked to unsafe sex or psychological problems such as depression and low self-

Sending sexually explicit text messages, or “sexting,” has become increasingly popular among young people. Although it may seem casual and fun, sexting can have serious repercussions. When 18-

SEX EDUCATION One way to learn about this relatively new phenomenon of sexting—

Teenagers who are provided a thorough education on sexual activity, including information on how to prevent pregnancy, are less likely to become pregnant (or get someone pregnant). Research shows that formal sex education increases safe-

SEXUAL ACTIVITY AND AGE Now let’s look at some data comparing the sexual behaviors of people at various stages of life. Would you expect to see major differences among people young, old, and in-

382

across the WORLD

Nearly half (44%) of adults participating in the Global Sex Survey said they were happy with their sex lives. Men were more likely than women to say they wanted to have sex more often (Global Sex Survey, 2005).

What They Are Doing in Bed . . . or Elsewhere

How often do people in New Zealand have sex? How many lovers has the average Israeli had? And are Chileans happy with the amount of lovemaking they do? These are just a few of the questions answered by the Global Sex Survey (2005), which, we dare to say, is one of the sexiest scientific studies out there (and which was sponsored by Durex, a condom manufacturer). We cannot report all the survey results, but here is a roundup of those we found most interesting:

How often do people in New Zealand have sex? How many lovers has the average Israeli had? And are Chileans happy with the amount of lovemaking they do? These are just a few of the questions answered by the Global Sex Survey (2005), which, we dare to say, is one of the sexiest scientific studies out there (and which was sponsored by Durex, a condom manufacturer). We cannot report all the survey results, but here is a roundup of those we found most interesting:

PEOPLE IN GREECE ARE HAVING THE MOST SEX.

People in Greece have the most sex—

an average of 138 times per year, or 2 to 3 times per week. People in Japan have the least amount of sex—

an average of 45 times per year, or a little less than once per week. The average age for losing one’s virginity is lowest among Icelanders (between 15 and 16) and highest for those from India (between 19 and 20).

Across nations, the average number of sexual partners is 9. If gender is taken into account, that number is a little higher for men (11) and lower for women (7).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed limitations of using self-

report surveys. People often resist revealing attitudes or behaviors related to sensitive topics, such as sexual activity. The risk is gathering data that do not accurately represent participants’ attitudes and beliefs, particularly with face- to- face interviews. Of respondents, 50% reported having sex in cars, 39% in bathrooms, and 2% in airplanes.

Nearly half the people around the world are happy with their sex lives.

As you reflect on these results, remember that surveys have limitations. People are not always honest when it comes to answering questions about personal issues (like sex), and the wording of questions can influence responses. Even if responses are accurate, we can only speculate about the beliefs and attitudes underlying them.

Sexual Dysfunction

sexual dysfunction A significant disturbance in the ability to respond sexually or to gain pleasure from sex.

When there is a “significant disturbance” in the ability to respond sexually or to gain pleasure from sex, we call this sexual dysfunction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In the National Health and Social Life Survey, researchers found 43% of women and 31% of men suffered from some sort of sexual dysfunction (Laumann, Paik, & Rosen, 1999). Temporary sexual difficulties may be caused by everyday stressors or situational issues but can be resolved once the stress or the situation has passed. Longer-

DESIRE Situational issues such as illness, fatigue, or frustration with one’s partner can lead to temporary problems with desire. In some cases, however, lack of desire is persistent and distressing. Although either sex can be affected, women tend to report desire problems more frequently than men (Brotto, 2010; Heiman, 2002).

383

AROUSAL Problems with arousal occur when the psychological desire to engage in sexual behavior is there, but the body does not cooperate. Men may have trouble getting or maintaining an erection, or they may experience a decrease in rigidity, which is called erectile disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). More than half of all men report they have occasionally experienced problems with erections (Hock, 2012). Women can also struggle with arousal. Female sexual interest/arousal disorder is apparent in reduced interest in sex, lack of initiation of sexual activities, reduced excitement, or decreased genital sensations during sexual activity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

ORGASM Female orgasmic disorder is diagnosed when a woman is consistently unable to reach orgasm, has reduced orgasmic intensity, or does not reach orgasm quickly enough during sexual activity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Men who experience frequent delay or inability to ejaculate might have a condition known as delayed ejaculation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Segraves, 2010). With this disorder, the ability to achieve orgasm and ejaculate is inhibited or delayed during partnered sexual activity. Men who have trouble controlling when they ejaculate (particularly during vaginal sex) may suffer from premature (early) ejaculation (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

PAIN Women typically report more problems with intercourse-

Sexually Transmitted Infections

LO 11 Identify the most common sexually transmitted infections.

sexually transmitted infections (STIs) Diseases or illnesses transmitted through sexual activity.

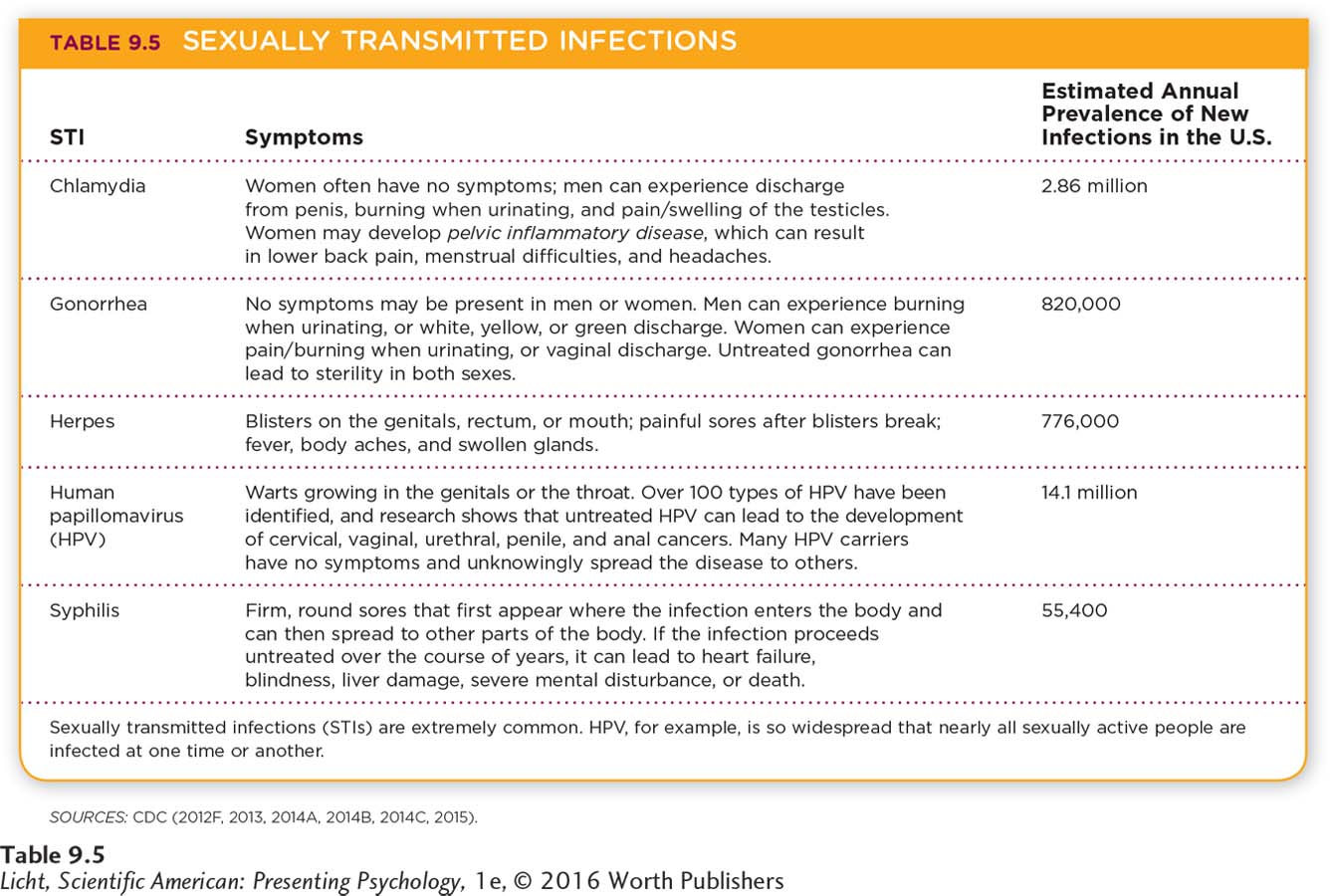

Although sex is pleasurable and exciting for most, it is not without risks. Many people carry sexually transmitted infections (STIs)—diseases or illnesses passed on through sexual activity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012f). There are many causes of STIs, but most are bacterial or viral (see Table 9.5, below for data on their prevalence). Bacterial infections such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia often clear up with antibiotics. Viral infections like genital herpes and human papillomavirus (HPV) have no cure, only treatments to reduce symptoms.

Apply This

PROTECT YOURSELF

The more sexual partners you have, the greater your risk of acquiring an STI. But you can lower your risk by communicating with your partner. People who know that their partners have had (or are having) sex with others face a lower risk of acquiring an STI than those who do not know. Why is this so? If you are aware of your partner’s activities, you may be more likely to take preventative measures, such as using condoms. Of course, there is always the possibility that your sexual partner (or you) has a disease but doesn’t know it. Some people with STIs are asymptomatic, meaning they have no symptoms. Others know they are infected but lie because they are ashamed, in denial, afraid of rejection, or for any number of reasons. Given all these unknowns, your best bet is to play it safe and use protection.

384

We have now explored many facets of motivation, from basic physiological drives to transcendent needs for achievement. As you may have guessed from the title of this chapter, motivations are intimately tied to emotions. In the sections to come, we will explore the complex world of human emotion, with a focus on fear and happiness.

show what you know

Question 1

1. Masters and Johnson studied the physiological changes that accompany sexual activity. They determined that men and women experience a similar sexual response cycle, including the following ordered phases:

excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution.

plateau, excitement, orgasm, and relaxation.

excitement, plateau, and orgasm.

excitement, orgasm, and resolution.

a. excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution.

Question 2

2. Explain how twin studies have been used to explore the development of sexual orientation.

Because monozygotic twins share 100% of their genetic make-

Question 3

3. ____________ and ____________ are both bacterial infections that are spread through unprotected sexual activity.

Syphilis; gonorrhea

Pelvic inflammatory disease; herpes

Human papillomavirus; herpes

Syphilis; acquired immune deficiency syndrome

a. Syphilis; gonorrhea