9.4 Emotion

SHARK ATTACK For those longing for a quiet beach escape, Ocracoke Island on the North Carolina coast is hard to beat. Wrapped in 16 miles of pristine beach, Ocracoke is a perfect place for building sandcastles, collecting seashells, and riding waves. Circumstances are ideal for young children, except for the occasional rip current. Oh, and there’s one more thing: Beware of sharks.

SHARK ATTACK For those longing for a quiet beach escape, Ocracoke Island on the North Carolina coast is hard to beat. Wrapped in 16 miles of pristine beach, Ocracoke is a perfect place for building sandcastles, collecting seashells, and riding waves. Circumstances are ideal for young children, except for the occasional rip current. Oh, and there’s one more thing: Beware of sharks.

One summer night in 2011, 6-

Jordan did the right thing. She applied pressure to the gushing wound and called for help. Lucy’s father Craig, who happens to be an emergency room doctor, rushed over and looked at the wound. Right away, he knew it was severe and needed immediate medical attention (Stump, 2011, July 26). In the moments following the attack, Lucy was remarkably calm. “Am I going to die?” she asked her mom. “Absolutely not,” Jordan replied. “Am I going to walk?” Lucy asked. “Am I going to have a wheelchair?” It was too early to know (CBS News, 2011, July 26, para. 16).

What Is Emotion?

Lucy Mangum was just 6 years old when she was attacked by a shark in the shallow waters of Ocracoke Island in North Carolina.

Unprovoked shark attacks are extremely uncommon, occurring less than 100 times per year worldwide. And most attacks are not fatal. To put things in perspective, you are 75 times more likely to be killed by a bolt of lightning and 33 times more likely to be killed by a dog (Florida Museum of Natural History, 2014). Despite their rarity, shark attacks seem to be particularly fear provoking. Maybe the thought of becoming the prey of a wild creature reminds us that we are still, at some level, animals: vulnerable players in the game of natural selection.

Fear is an emotion you experience throughout your life. When you were a baby, you might have been afraid of the vacuum cleaner or the hair dryer. As you matured, your fears may have shifted to the dog next door or the monster in the closet. These days you might be scared of growing older, being diagnosed with a serious disease, or losing someone you love.

LO 12 Define emotions and explain how they are different from moods.

emotion A psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience, a physiological component, and a behavioral expression.

But what exactly is fear? That’s an easy question: Fear is an emotion. Now here’s the hard question: What is an emotion? An emotion is a psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience. In other words, emotion is intensely personal; we cannot actually feel each other’s emotions firsthand. Emotion also has a physiological component; it is not only “in our heads.” For example, anger can make you feel hot, anxiety might cause sweaty palms, and sadness may sap your physical energy. Finally, emotion entails a behavioral expression. We scream and run when frightened, gag in disgust, and shed tears of sadness. Think about the last time you felt joyous. What was your inner experience of that joy, how did your body react, and what would someone have noticed about your behavior?

Thus, emotion is a subjective psychological state that includes both physiological and behavioral components. But are these three elements—

MOODS VERSUS EMOTIONS Most psychologists agree that emotions are different from moods. Emotions are quite strong, but they don’t generally last as long as moods, and they are more likely to have an identifiable cause. An emotion is initiated by a stimulus, and it is more likely than a mood to motivate someone to action. Moods are longer-

Now let’s see how the three distinguishing characteristics of emotion (as opposed to moods) might apply to Lucy’s situation. When Lucy’s mother saw the wound from the shark bite, she remembers feeling “afraid” (CBS News, 2011, July 26). Her emotion (1) had a clear cause (the shark attacking her daughter), (2) likely produced a physiological reaction (heart racing, for example), and (3) motivated her to action (applying pressure to the wound and calling for help).

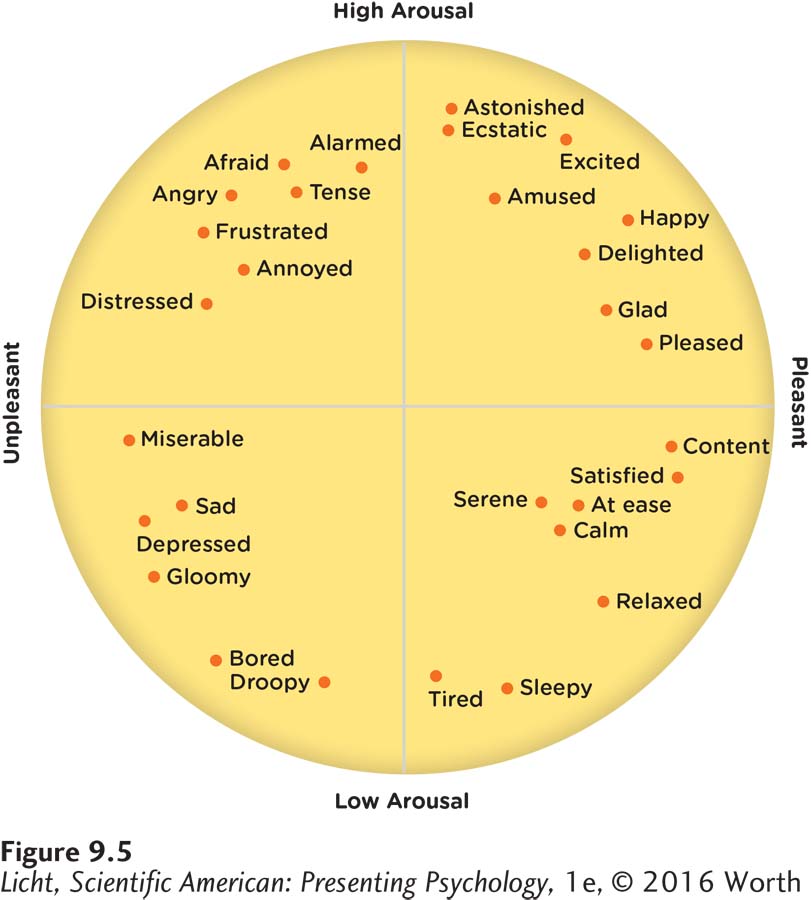

Emotions can be compared and contrasted according to their valence (how pleasant or unpleasant they are) and their arousal level.

© 1980 by the American Psychological Association. Adapted with permission from Russell (1980)

LANGUAGE AND EMOTION If you were Lucy’s mom, what words might you use to describe your fear—

Rather than focusing on words or labels, scholars typically characterize emotions along different dimensions. Izard (2007) suggests that we can describe emotions according to valence and arousal (Figure 9.5). The valence of an emotion refers to how pleasant or unpleasant it is. Happiness, joy, and satisfaction are on the pleasant end of the valence dimension; anger and disgust lie on the unpleasant end. The arousal level of an emotion describes how active, excited, and involved a person is while experiencing the emotion, as opposed to how calm, uninvolved, or passive she may be. With valence and arousal level, we can compare and contrast emotions. The emotion of ecstasy, for example, has a high arousal level and a positive valence. Feeling relaxed has a low arousal level and a positive valence. When Lucy looked down and saw the shark, she likely experienced an intense fear—

Emotion and Physiology

FIGHT BACK Within 35 minutes of the attack, Lucy was lifted off Ocracoke Island by helicopter and was on her way to a trauma center in Greenville, North Carolina. The damage to her leg was extensive, with large tears to the muscle and tendons. She would need two surgeries, extensive physical therapy, and a wheelchair for some time after leaving the hospital (WRAL.com, 2011, July 26).

FIGHT BACK Within 35 minutes of the attack, Lucy was lifted off Ocracoke Island by helicopter and was on her way to a trauma center in Greenville, North Carolina. The damage to her leg was extensive, with large tears to the muscle and tendons. She would need two surgeries, extensive physical therapy, and a wheelchair for some time after leaving the hospital (WRAL.com, 2011, July 26).

How did Lucy hold up during this period of extreme stress? According to lead surgeon Dr. Richard Zeri, the 6-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we explained how the sympathetic nervous system prepares the body to respond to an emergency, whereas the parasympathetic nervous system brings the body back to a noncrisis mode through the “rest-

Such acts of self-

LO 13 List the major theories of emotion and describe how they differ.

Does laughing make you happy? According to the James–

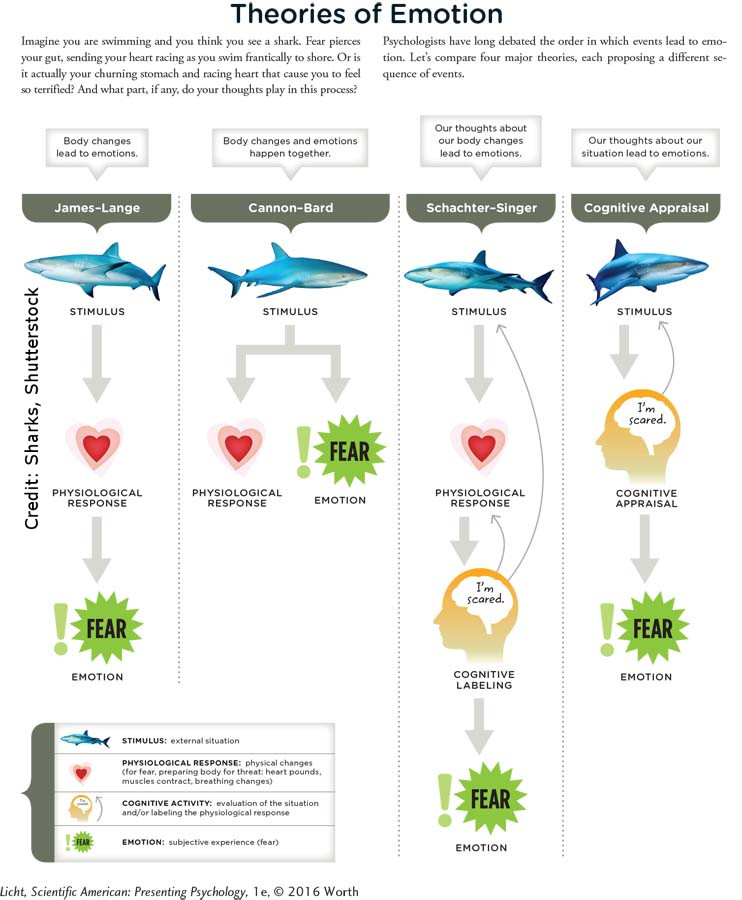

Most psychologists agree that emotions and physiology are deeply intertwined, but they have not always agreed on the precise order of events. What happens first: the body changes associated with emotion or the emotions themselves? That’s a no-

James–

JAMES–

INFOGRAPHIC 9.3

How might the James–

The implication of the James–

However, critics of the James–

Cannon–

Most people would be terrified to see a snake slithering across their bedsheets. Does the feeling of fear come before or after the heart starts racing and the body flinches? According to the Cannon–

CANNON–

Let’s use the Cannon–

When the neural information reaches the cortex and hypothalamus, several things could happen. First, the “thalamic–

Critics of the Cannon–

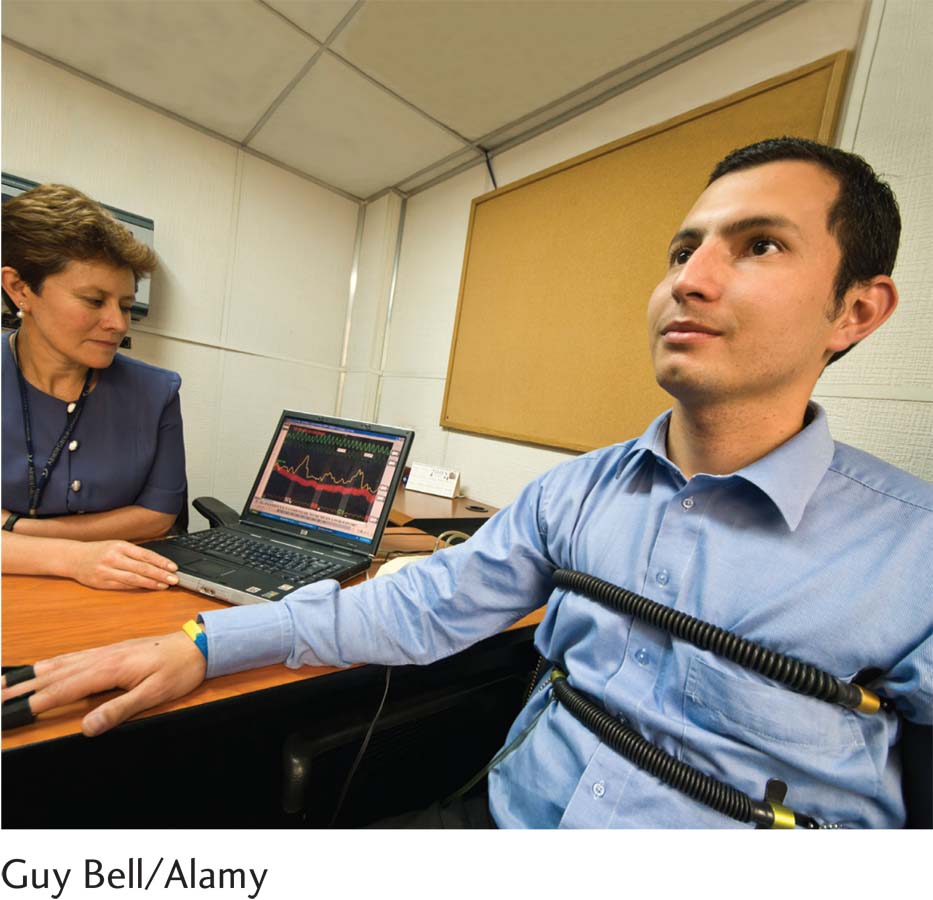

The polygraph, or so-

Cognition and Emotion

Schachter–

SCHACHTER–

To test their theory, Schachter and Singer injected participants (male college students) with either epinephrine to mimic physiological reactions of the sympathetic nervous system (such as increased blood pressure, respiration, and heart rate) or a placebo. The researchers also divided the participants into the following groups: those who were informed correctly about possible side effects (for example, tremors, palpitations, flushing, or accelerated breathing), those who were misinformed about side effects, and others who were told nothing about side effects.

The participants were left in a room with a “stooge,” a confederate secretly working for the researcher, who was either euphoric or angry. When the confederate behaved euphorically, the participants who had been given no explanation for their physiological arousal were more likely to report feeling happy or appeared happier. When the confederate behaved angrily, participants given no explanation for their arousal were more likely to appear or report feeling angry. Through observation and self-

Some have criticized the Schachter–

COGNITIVE APPRAISAL AND EMOTION Rejecting the notion that emotions result from cognitive labels of physiological arousal, Richard Lazarus (1984, 1991a) suggested that emotion is the result of the way people appraise or interpret interactions they have in their surroundings. It doesn’t matter if someone can label an emotion or not; he will experience the emotion nonetheless. We’ve all felt emotions such as happiness, anxiety, and shame, and we don’t need an agreed upon label or word to experience them. Babies, for example, can feel emotions long before they are able to label them with words.

cognitive appraisal approach Suggests that the appraisal or interpretation of interactions with surroundings causes an emotional reaction.

Lazarus also suggested that emotions are adaptive, because they help us cope with the surrounding world. In a continuous feedback loop, as an individual’s appraisal or interpretation of his environment changes, so do his emotions (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Lazarus, 1991b). Emotion is a very personal reaction to the environment. This notion became the foundation of the cognitive appraisal approach to emotion (Infographic 9.3), which suggests that the appraisal causes an emotional reaction. In contrast, Schachter–

Responding to the cognitive-

One of the main areas of disagreement among the theories just described concerns the role of cognition. Forgas (2008) proposed that the association between emotion and cognitive activity is complex and bidirectional: “Cognitive processes determine emotional reactions, and, in turn, affective states influence how people remember, perceive, and interpret social situations and execute interpersonal behaviors” (p. 99).

It’s Written All over Your Face

We now know that emotions are complex and closely related to cognition, physiology, and perception. But how do these internal changes affect a person’s appearance? Think about the clues you rely on when trying to “read” another person’s emotions. Where do you look for signs of anger, sadness, or surprise? It’s written all over his face, of course.

Despite the large cast on her leg, Lucy looks happy and healthy. Her shark-

FACE VALUE Lucy was lucky. With a 90% tear to the muscle and tendon and a severed artery, she could have easily lost her leg. But the surgeries went well. Just a week after the horrific incident, she was flashing a bashful grin on national television. Seated between mom and dad, Lucy played with her mother’s fingers, squirmed, and then nestled her head under her father’s arm. She looked as bright-

FACE VALUE Lucy was lucky. With a 90% tear to the muscle and tendon and a severed artery, she could have easily lost her leg. But the surgeries went well. Just a week after the horrific incident, she was flashing a bashful grin on national television. Seated between mom and dad, Lucy played with her mother’s fingers, squirmed, and then nestled her head under her father’s arm. She looked as bright-

“The prognosis is great,” Lucy’s father Craig told TODAY’s Ann Curry. “It’s going to take some time and some physical therapy, but she’s going to be, you know, back and running and playing like she should” (MSNBC.com, 2011, July 26). The look on Craig’s face was calm, happy. Jordan also appeared relieved. Their little girl was going to be okay.

Suppose you knew nothing about Lucy’s shark attack, and someone showed you an image of Lucy’s parents during that television interview. Would you be able to detect the relief in their facial expressions? How about someone from Nepal, Trinidad, or Bolivia: Would a cultural outsider also be able to “read” the emotions written across Craig and Jordan’s faces?

LO 14 Discuss evidence to support the idea that emotions are universal.

Writing in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872/2002), Charles Darwin suggested that interpreting facial expressions is not something we learn but rather is an innate ability that evolved because it promotes survival. Sharing the same facial expressions allows for communication. Being able to identify the emotions of others—

A smile in India (right) means the same thing as a smile in Lithuania (middle) or Kenya (left). Facial expressions associated with basic emotions like happiness, disgust, and anger are strikingly similar across cultures (Ekman & Friesen, 1971).

EKMAN’S FACES Some four decades ago, psychologist Paul Ekman traveled to a remote mountain region of New Guinea to study an isolated group of indigenous peoples. Ekman and his colleagues were very careful in selecting their participants, choosing only those who were unfamiliar with Western facial behaviors—

Further evidence for the universal nature of these facial expressions is apparent in children born blind; although they have never seen a human face demonstrating an emotion, their smiles and frowns are similar to those of sighted children (Galati, Scherer, & Ricci-

LO 15 Indicate how display rules influence the expression of emotion.

across the WORLD

Can You Feel the Culture?

Although the expression of some basic emotions appears to be universal, culture acts like a filter, determining the appropriate contexts in which to exhibit them. According to Mohamed (the Somali American we introduced earlier in the chapter), people from Somalia tend to be much less expressive than those born in the United States. “I have cousins who have just come to America, and even [now] when they have been here for about five years, they still like to keep to themselves about personal feelings,” says Mohamed. This is especially true when it comes to interacting with people outside the immediate family.

Although the expression of some basic emotions appears to be universal, culture acts like a filter, determining the appropriate contexts in which to exhibit them. According to Mohamed (the Somali American we introduced earlier in the chapter), people from Somalia tend to be much less expressive than those born in the United States. “I have cousins who have just come to America, and even [now] when they have been here for about five years, they still like to keep to themselves about personal feelings,” says Mohamed. This is especially true when it comes to interacting with people outside the immediate family.

display rules Framework or guidelines for when, how, and where an emotion is expressed.

WHEN TO REVEAL, WHEN TO CONCEAL

These differences Mohamed observes are probably reflections of display rules. A culture’s display rules provide the framework or guidelines for when, how, and where an emotion is expressed. Think about some of the display rules in American culture. Negative emotions such as anger are often hidden in social situations. Suppose you are furious at a friend for forgetting to return a textbook she borrowed last night. You probably won’t reveal your anger as you sit among other students. Other times display rules compel you to express an emotion you are not feeling. Your friend gives you a birthday gift that really isn’t you. Do you say, “This is not my style. I think I’ll exchange it for a store credit,” or “Thank you so much” and smile graciously?

Generally speaking, Americans tend to be fairly expressive. Showing emotion, particularly positive emotions, is socially acceptable. This is less the case in Japan, where people rarely reveal their feelings in public. One group of researchers secretly videotaped Japanese and American students while they were watching film clips that included surgeries, amputations, and other events commonly viewed as repulsive. Japanese and American participants showed no differences in their responses to the clips when they didn’t think researchers were watching. The great majority demonstrated similar facial expressions of disgust and emotional reactions in response to the stress-

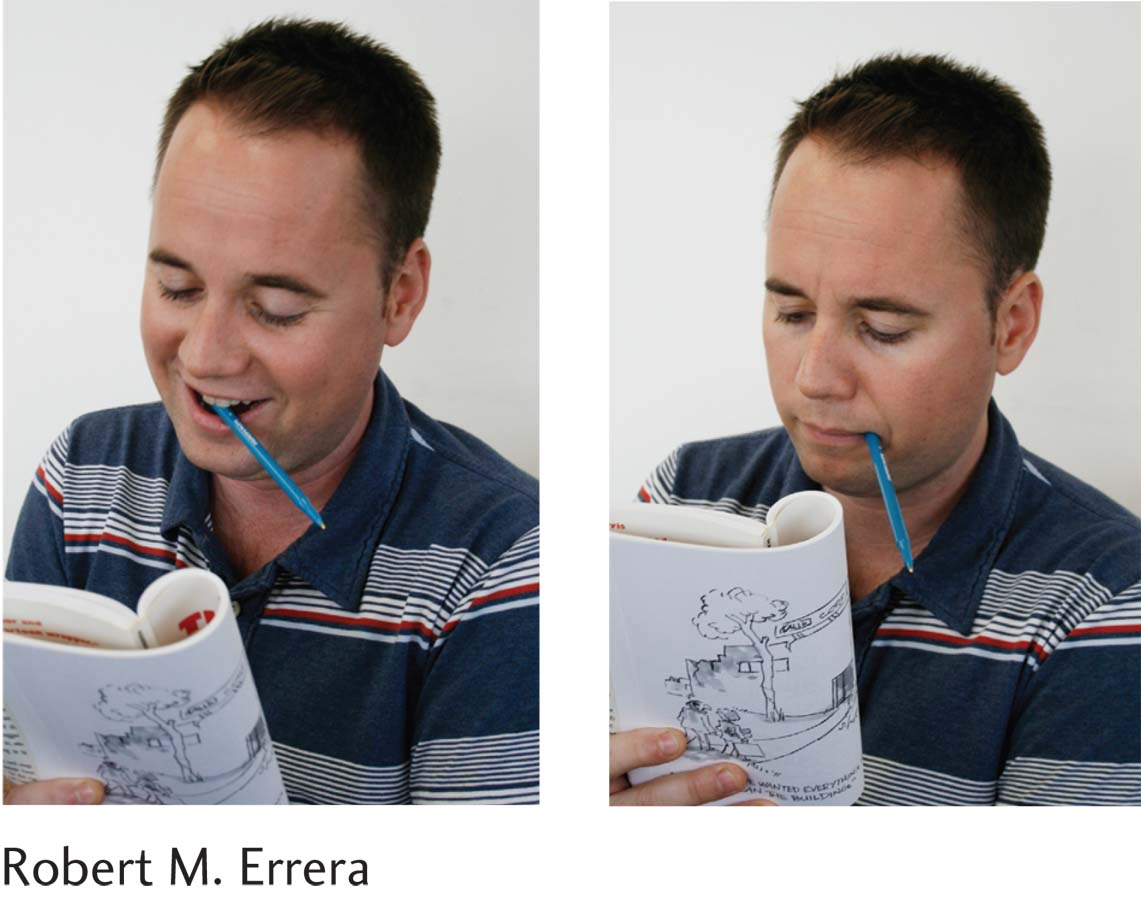

Holding a pencil between your teeth (left) will probably put you in a better mood than holding it with your lips closed (right). This is because the physical act of smiling, which occurs when you place the pencil in your teeth, promotes feelings of happiness. So next time you’re feeling low, don’t be afraid to flex those smile muscles!

FACIAL FEEDBACK HYPOTHESIS While we are on the topic of facial expressions, let’s take a brief detour back to the very beginning of the chapter when Mohamed arrived in his first-

facial feedback hypothesis The facial expression of an emotion can affect the experience of that emotion.

Believe it or not, the simple act of smiling can make a person feel happier. Although facial expressions are caused by the emotions themselves, they sometimes affect the experience of those emotions. This is known as the facial feedback hypothesis (Buck, 1980), and if it is correct, we should be able to manipulate our emotions through our facial activities. Try this for yourself.

Take a pen and put it between your teeth, with your mouth open for about half a minute. Now, consider how you are feeling. Next, hold the pen with your lips, making sure not to let it touch your teeth, for half a minute. Again, consider how you are feeling.

try this

If you are like the participants in a study conducted by Strack, Martin, and Stepper (1988), holding the pen in your teeth should result in your seeing the objects and events in your environment as funnier than if you hold the pen with your lips. Why would that be? Take a look at the photo to the right and note how the person holding the pen in his teeth seems to be smiling—

We are now nearing the end of this chapter—

show what you know

Question 1

1. ____________ is a psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience, physiological component, and behavioral expression.

Valence

Instinct

Mood

Emotion

d. Emotion

Question 2

2. On the way to a wedding, you get mud on your clothing. Describe how your emotion and mood would differ.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following definitions. Emotion is a psychological state that includes a subjective or inner experience. It also has a physiological component and entails a behavioral expression. Emotions are quite strong, but they don’t generally last as long as moods. In addition, emotions are more likely to have identifiable causes (that is, be reactions to stimuli that provoked them) and they are more likely to motivate a person to action. Moods are longer-

Question 3

3. The ____________ theory of emotion suggests that changes in the body and behavior lead to the experience of emotion.

James–

Question 4

4. ____________ of a culture provide a framework for when, how, and where an emotion is expressed.

Beliefs

Display rules

Feedback loops

Appraisals

b. Display rules

Question 5

5. Name two ways in which the Cannon–

Answers may vary. See Infographic 9.3. The Cannon–

Question 6

6. What evidence exists that emotions are universal?

Darwin suggested that interpreting facial expressions is not something we learn but rather is an innate ability that evolved because it promotes survival. Sharing the same facial expressions allows for communication. Research on an isolated group of indigenous peoples in New Guinea suggests that the same facial expressions represent the same basic emotions across cultures. In addition, the fact that children born deaf and blind have the same types of expressions of emotion as children who are not deaf or blind suggests the universal nature of these displays, and thus the emotions that trigger them.