4.1 Geospatial Lab ApplicationGPS Applications

4.1 Geospatial Lab ApplicationGPS Applications

This chapter’s lab will examine the use of the Global Positioning System in a variety of activities. The big caveat is that the lab can’t assume that you have access to a GPS receiver unit and that you’re able to use it in your immediate area (and unfortunately, we can’t issue you a receiver with this book). It would also be useless to describe exercises involving you running around (for instance) Boston, Massachusetts, collecting GPS data, when you may not live anywhere near Boston.

This lab will therefore use the free Trimble Planning Software for examining GPS satellite positions and other planning factors for the use of GPS for data collection. In addition, some sample Web resources will be used to examine related GPS concepts for your local area.

For some good introductory information about Trimble Planning Software (whose info helped guide the development of this lab), check out an article by Leszek Pawlowicz entitled “Determining Local GPS Satellite Geometry Effects On Position Accuracy.” This article is available online at http://freegeographytools.com/2007/determining-local-gps-satellite-geometryeffects-on-position-accuracy.

Important note: Though this lab is short, it can be significantly expanded if you have access to GPS receivers. If you do, some of the geocaching exercises described in Section 4.5 of this lab can be implemented. Alternatively, rather than just examining cache locations on the Web (as in Section 4.4), you can use the GPS equipment to hunt for the caches themselves.

Objectives

The goals for you to take away from this lab are:

to examine satellite visibility charts to determine how many satellites are available in a particular geographic location, and to find out when during the day these satellites are available.

to examine satellite visibility charts to determine how many satellites are available in a particular geographic location, and to find out when during the day these satellites are available. to read a DOP chart to determine what times of day have higher and lower values for DOP for a particular geographic location.

to read a DOP chart to determine what times of day have higher and lower values for DOP for a particular geographic location. to explore some Web resources to see where publicly available geocaches or permanent marker sites are that you can track down with a GPS receiver.

to explore some Web resources to see where publicly available geocaches or permanent marker sites are that you can track down with a GPS receiver.

101

Using Geospatial Technologies

The concepts you’ll be working with in this lab are used in a variety of real-world applications, including:

precision agriculture, in which farmers utilize GPS to find more efficient means of maintaining crops through having access to very accurate crop locations.

precision agriculture, in which farmers utilize GPS to find more efficient means of maintaining crops through having access to very accurate crop locations. geologists use GPS for collecting location data while in the field, like the precise coordinates of groundwater wells.

geologists use GPS for collecting location data while in the field, like the precise coordinates of groundwater wells.

Obtaining Software

The current version of Trimble Planning Software (2.9) is available for free download at http://ww2.trimble.com/planningsoftware_ts.asp.

Important note: Software and online resources sometimes change fast. This lab was designed with the most recently available version of the software at the time of writing. However, if the software or Websites have significantly changed between then and now, an updated version of this lab (using the newest versions) is available online at http://www.whfreeman.com/shellito2e.

Lab Data

There is no data to copy in this lab. All data comes as part of the Trimble Planning Software that is installed with the program or can be downloaded as part of the lab.

Localizing This Lab

Note: This lab uses one location and one date to keep information consistent. Although this lab looks at GPS sky conditions in Orlando, Florida, there are many more geographic locations that can be selected using Trimble Planning Software. Its purpose is to be able to evaluate local conditions for GPS planning—so rather than selecting Orlando, find the closest city to your location and examine that data instead. You can also use today’s date rather than the one used in the lab.

102

Similarly, in Section 4.4 of the lab, you’ll be examining Web resources for geocaching locations in Orlando, Florida. Use your own zip code rather than the one for Orlando and see what’s near your home or school instead.

4.1 Trimble Planning Software Setup

- Start the Trimble Planning Software program—the default install folder is called Trimble Office—and then look inside the Utilities folder where you will find an icon called Planning. This will launch the program.

- The first thing to do is download a copy of the most current almanac file. This can be done by going to Trimble’s Website at http://ww2.trimble.com/gpsdataresources.shtml and selecting the option for GPS/GLONASS almanac in Trimble Planning file format. Download the file (it’s a small text file) by right-clicking on the hyperlink (GPS/GLONASS almanac in Trimble Planning file format) and click on Save Link As… from the dialog box. Click on the Save button and the file “almanac.alm”; will be downloaded to your computer.

- In the Planning program, select Load from the Almanac pull-down menu. In the Almanac Files dialog box, navigate to the location where you saved the almanac.alm file, select it, and then click Open. A summary of the satellite information contained in the file will appear on the screen and the almanac information will be loaded.

4.2 Local Area GPS Information

The visibility of GPS satellites will change with the time of day and your position on Earth. The Trimble Planning program will allow you to examine data from stations around Earth to determine GPS information.

- From the File pull-down menu, select Station. You could also select the Station icon from the toolbar:

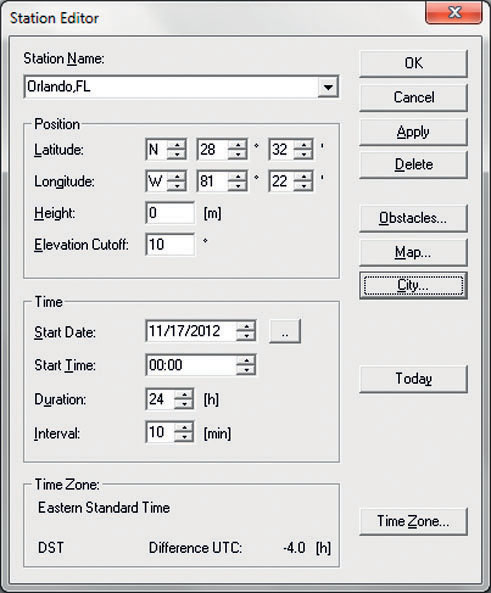

The Station Editor dialog box will open.

(Source: Trimble)

(Source: Trimble)

(Source: Trimble)

(Source: Trimble) - The Station Editor allows you to select any station across the world. For this portion of the lab, we’ll be examining GPS satellite visibility near Orlando, Florida.

- To select an area, click on the City… button on the right. From the pull-down list, choose Orlando, FL.

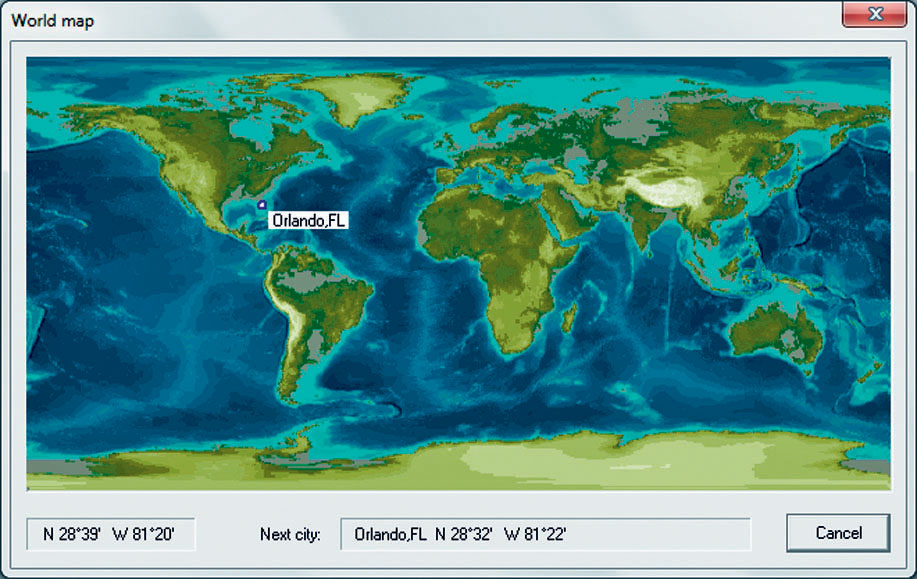

Important note: An alternate method for selecting a location is to click on the Map… button. A world map will appear that allows you to select based on a geographic location—scroll the mouse across the map to see what options are available, and then double-click on the city you want. (Source: Trimble)

(Source: Trimble) - Make sure the Time Zone is set to Eastern Time (US & Canada).

- You can also enter values for time and date. Change the date for this lab to 11/17/2012 (as this is the date used for measurements).

- When the settings are correct, click OK.

- The Trimble Planning Software will now report back satellite information in relation to Orlando.

4.3 Satellite Visibility Information

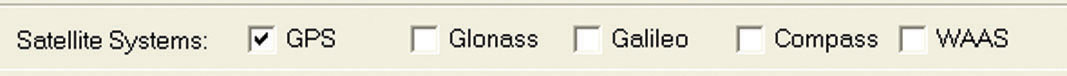

- Trimble Planning Software allows you to examine satellite visibility (and other factors) from a local area at various times throughout the day. To choose which group of satellites you’re examining, put checkmarks in the Satellite Systems boxes below the toolbar:

Source: Trimble)

Source: Trimble) - For now, only select the GPS box.

- First, we’ll examine the number of GPS satellites potentially visible from Orlando at various points of the day. From the Graphs pull-down menu, select Number of Satellites. You could also choose the Number of Satellites icon from the toolbar:

Source: Trimble)

Source: Trimble) - The number of satellites visibility graph will appear, showing the number of visible satellites on the y-axis and a 24-hour time frame on the x-axis.

Question 4.1

At what times of day are the maximum number of GPS satellites visible? What is this maximum number?

Question 4.2

At what times of day are the minimum number of GPS satellites visible? What is this minimum number?

- To determine which satellites are visible at specific times, go to the Graphs pull-down menu, choose Visible Satellites, and then choose General Visibility. You could also choose the Visibility icon from the toolbar:

Source: Trimble)

Source: Trimble) - The Visibility graph will appear, showing the specific GPS satellite number on the y-axis and a 24-hour time frame on the x-axis.

Question 4.3

Which satellites are visible from Orlando at noon?

Question 4.4

Which satellites are visible from Orlando at 4:00 pm?

- To examine the Position Dilution of Precision (PDOP) at a particular time of day, from the Graphs pull-down menu select DOP, then select All Together. You could also choose the DOPs icon from the toolbar:

(Source: Trimble)

(Source: Trimble) - The graph for Dilution of Precision will appear, showing the values for DOP on the y-axis and a 24-hour time frame on the x-axis.

Question 4.5

At what time(s) of day will the maximum values for DOP be encountered? What is this maximum value?

Question 4.6

At what time(s) of day will the minimum values for DOP be encountered? What is this minimum value?

- Take a look at all the graphs and answer Question 4.7.

Question 4.7

Just based on satellite visibility and DOP calculations, what would be some of the “best” (i.e., peak) times to perform GPS field measurements in Orlando? What would be some of the “worst” times?

- Close all the graphs, then uncheck the GPS box in Satellite Systems and place a checkmark in the WAAS box instead.

- Examine the Visibility chart for the available WAAS satellites.

Question 4.8

How many WAAS Satellites does Trimble Planning say are available? At what times are they available? Why is this?

- Next, examine the Sky Plot (a chart showing the position of the satellites in orbit) for these WAAS satellites. From the Graphs pull-down menu, select Sky Plot. You could also choose the Sky Plot icon from the toolbar:

(Source: Trimble)

(Source: Trimble)Question 4.9

Based on the information from the visibility chart and the sky plot, what satellites are these? (Hint: The software says “WAAS,” but are they all strictly functional WAAS satellites? You may have to look up some names.)

- At this point, you can close all windows and exit the Trimble Planning Software.

106

4.4 GPS and Geocaching Web Resources

With some preliminary planning information available from Trimble Planning, you can get ready to head out with a GPS receiver. For some starting points for GPS usage, try the following:

- Open a Web browser and go to http://www.geocaching.com. This Website is home to several hundred thousand geocaches at locations throughout the world. The Website will list the coordinates of geocaches (small hidden items) so that you can use a GPS to track them down.

- On the main page of the Website, enter 32801 (one of Orlando’s many ZIP codes) in the box that asks for a ZIP code. Several potential geocaches should appear on the next Web page.

- You can also search for benchmarks (permanent survey markers set into the ground) by using the Website’s Find A Benchmark option (at the time of writing, it was listed at the bottom of the Webpage). On the benchmark page, input 32801 for the ZIP code to search for.

Question 4.10

How many benchmarks can be located within less than one mile of the Orlando 32801 ZIP code? What are the coordinates of the closest one to the origin of the ZIP code?

4.5 GPS and Geocaching Applications

As we touched on back in the introduction, there’s a lot more that can be done application-wise if you have access to a GPS receiver. For starters, you can find the positions of some nearby caches or benchmarks by visiting http://www.groundspeak.com or http://www.geocaching.com and then tracking them down using the receiver and your land navigation skills. However, there are a number of different ways that geocaching concepts can be adapted so that they can be explored in a classroom setting.

The first of these is based on material developed by Dr. Mandy Munro-Stasiuk and published in her article “Introducing Teachers and University Students to GPS Technology and Its Importance in Remote Sensing Through GPS Treasure Hunts” (see the online chapter references for the full citation of the article). Like geocaching, the coordinates of locations have been determined ahead of time by the instructor and given to the participants (such as university students or K–12 teachers attending a workshop) along with a GPS receiver. Having only sets of latitude/longitude or UTM coordinates, the participants break into groups and set out to find the items (such as statues, monuments, building entrances, or other objects around their campus or local area). The students are required to take a photo of each object they find, and all participants must be present in the photo (this usually results in some highly creative picture taking). The last twist is that the “treasure hunt” is a timed competition with the team that returns first (and having found all the correct items) earning some sort of reward, such as extra credit in the class, or—at the very least—bragging rights for the remainder of the class. In this way, participants learn how to use the GPS receivers, how to tie coordinates to real-world locations, and they also get to improve their land navigation skills by reinforcing their familiarity with concepts such as how northings and eastings work in UTM.

107

A similar version of this GPS activity is utilized during the OhioView SATELLITES Teacher Institutes (see Chapter 15 for more information on this program). Again, participants break up into groups with GPS receivers, but this time each group is given a set of small trinkets (such as small toys or plastic animal figures) and instructed to hide each one, registering the coordinates of the hiding place with their GPS receiver, and writing them on a sheet of paper. When the groups reconvene, the papers with the coordinates are switched with another group, and each group now has to find the others’ hidden objects. In this way, each group sets up its own “geocaches” and then gets challenged to find another group’s caches. Like before, this is a timed lab with a reward awaiting the team of participants that successfully finds all of the hidden items at the coordinates they’ve been given. This activity helps to reinforce not only GPS usage and land navigation, but also the ties between real-world locations and the coordinates being recorded and read by a GPS receiver. Both of these activities have proven highly successful in reinforcing these concepts to the participants involved.

However you get involved with geocaching, a helpful utility for managing geocached data and waypoints from different software packages is the Geocaching Swiss Army Knife, available for free download at http://www.gsak.net. This utility comes with a free trial.

Closing Time

This lab illustrated some initial planning concepts and some directions in which to take GPS field work (as well as some caches and benchmarks that are out there waiting for you to find), to help demonstrate some of the concepts delineated in the chapter. The two geocaching field exercises described above can also be adapted for classroom use to help expand the computer portion of this lab with some GPS field work as well.

Starting with Chapter 5, you’ll begin to integrate some new concepts of geographic information systems to your geospatial repertoire.

108