Culture and Children’s Emotional Development

Although people in all cultures appear to experience most of the same basic emotions, there is considerable cultural variation in the degree to which certain emotions are expressed. One reason for this may be genetic, in that people in different racial or ethnic groups may tend, on average, to have somewhat different temperaments. This possibility has been tentatively suggested by cross-cultural studies that were conducted with young infants to minimize the potential for the results to be affected by socialization. One such study found that, in general, 11-month-old European American infants react more strongly to unfamiliar stimuli than do Chinese or Chinese American babies and cry or smile more in response to evocative events (e.g., scary toys or a vanishing object) (Freedman & Freedman, 1969). Another study found that, compared with Chinese infants, American infants also respond more quickly to negative emotion-inducing events such as having their arm held down so they cannot move it (Camras et al., 1998).

A more obvious contributor to cross-cultural differences in infants’ emotional expression is the diversity of parenting practices. In Central Africa, for example, the infants in an Ngandu community fuss and cry more than infants in an Aka community do. This may be attributable to differences in caregiving practices related to the contrasting lifestyles of these two groups. Aka infants are almost always within arm’s reach of someone who can feed or hold them when the need arises. The Ngandu leave their infants alone more often. Thus, Aka infants may cry and fuss less because they have more physical contact with caregivers and their needs are met more quickly (Hewlett et al., 1998).

The influence of cultural factors on emotional expression is strikingly revealed by a comparison of East Asian and American children. In one study, Japanese and American preschoolers were asked to say what they would do in hypothetical situations of conflict and distress, such as being hit or seeing a peer knock down a tower of blocks they had just built. American preschoolers expressed more anger and aggression in response to these vignettes than did Japanese children. This difference may have to do with the fact that American mothers appear to be more likely than Japanese mothers to encourage their children to express their emotions in situations such as these (Zahn-Waxler et al., 1996). These tendencies are in keeping with the high value European American culture places on independence, self-assertion, and expressing one’s emotions, even negative ones (Zahn-Waxler et al., 1996). In contrast, Japanese culture emphasizes interdependence, the subordination of oneself to one’s group, and, correspondingly, the importance of maintaining harmonious interpersonal relationships. A similar contrast is found in other East Asian cultures, such as in China, where mothers often discourage their children from expressing negative emotion, especially anger (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Matsumoto, 1996; Mesquita & Frijda, 1992). As a consequence, children in such societies learn not to communicate certain negative feelings (Raval & Martini, 2009).

415

Cultures also differ in the degree to which they promote or discourage specific emotions, and these differences are often reflected in parents’ socialization of emotion. For example, Chinese culture strongly emphasizes the need to be aware of oneself as embedded in a larger group and to maintain a positive image within that group. Thus, shame would be expected to be a powerful emotion—important for self-reflection and self-perfection (Fung, 1999; Fung & Chen, 2001) and particularly useful for inducing compliance in children. In fact, Chinese (Taiwanese) parents frequently try to induce shame in their preschool children when they transgress, typically pointing out that the child’s behavior is judged negatively by people outside the family and that the child’s shame is shared by other family members (Fung & Chen, 2001). Because of this cultural emphasis, it is likely that children in this society experience shame more frequently than do children in many Western cultures. Moreover, when children in Western cultures do experience shame or sadness, their mothers seem to be most concerned with helping them feel better about themselves. In contrast, Chinese mothers more often than Western mothers use the situation as an opportunity to teach proper conduct and help their child understand how to conform to social expectations and norms—for example, asking “Isn’t it wrong for you to get mad at Papa?” (Cheah & Rubin, 2004; Friedlmeier, Corapci, & Cole, 2011; Q. Wang & Fivush, 2005).

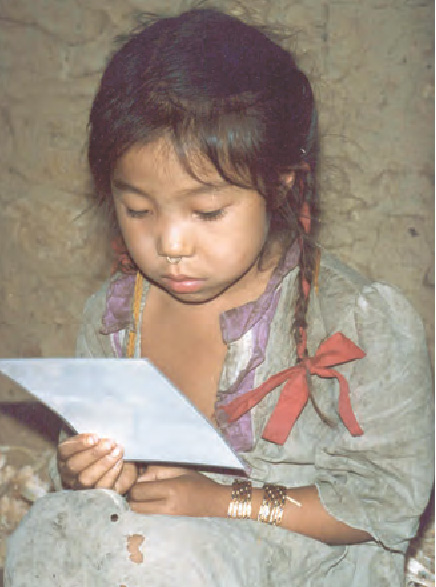

Another striking example of cultural influences on emotional socialization is provided by the Tamang in rural Nepal. The Tamang are Buddhists who place great value on keeping one’s sem (mind-heart) calm and clear of emotion, and they believe that people should not express much negative emotion because of its disruptive effects on interpersonal relationships. Consequently, although Tamang parents are responsive to the distress of infants, they often ignore or scold children older than age 2 when those children express anger, and they seldom offer explanations or support to reduce children’s anger. Such parental reactions are not typical of all Nepali groups, however; for example, parents of Brahman Nepali children respond to children’s anger with reasoning and yielding.

Of particular interest is the fact that although nonsupportive parental behavior comparable to that of the Tamang has been associated with low social competence in U.S. children, it does not seem to have a negative effect on the social competence of Tamang children. Because of the value placed on controlling the expression of emotion in Tamang culture, parental behaviors that would seem dismissive and punitive to American parents likely take on a different meaning for Tamang parents and children and probably have different consequences (P. M. Cole & Dennis, 1998; P. M. Cole et al., 2006).

416

Parents’ ideas about the usefulness of various emotions also vary in different cultural and regional groups within the United States. In a study of African American mothers living in dangerous neighborhoods, mothers valued and promoted their daughters’ readiness to express anger and aggressiveness in situations related to self-protection because they wanted their daughters to act quickly and decisively to defend themselves when necessary. One way they did this was to play-act the role of an adversary, teasing, insulting, or challenging their daughters in the midst of everyday interactions. An example of this is provided by Beth’s mother, who initiated a teasing event by challenging Beth (27 months old) to fight:

“Hahahaha, Hahaha. Hahahaha. [Provocative tone:] You wanna fight about it?” Beth laughed. Mother laughed. Mother twice reiterated her challenge and then called Beth an insulting name, “Come on, then, chicken.” Beth retorted by calling her mother a chicken. The two proceeded to trade insults through the next 13 turns, in the course of which Beth marked three of her utterances with teasing singsong intonation and aimed a shaming gesture (rubbing one index finger across the other) at her mother. The climax occurred after further mock provocation from the mother, when Beth finally raised her fists (to which both responded with laughter) and rushed toward her mother for an exchange of ritual blows.

(P. Miller & Sperry, 1987, pp. 20–21)

It is unlikely that mothers in a less difficult and dangerous neighborhood would try to promote the readiness to express aggression in their children, especially in their daughters. Thus, the norms, values, and circumstances of a culture or subcultural group likely contribute substantially to differences among groups in their expression of emotion.

review:

Children’s tendencies in regard to experiencing and regulating emotions may be affected by differences in temperament among different groups of people. These tendencies may also be influenced by differences in parenting practices, which in turn are often affected by cultural differences in beliefs about what emotions are valued, and when and where emotions should be expressed.