Children’s Understanding of Emotion

Another key influence on children’s emotional reactions and regulation of emotion is their understanding of emotion—that is, their understanding of how to identify emotions, as well as their understanding of what emotions mean, their social functions, and what factors affect emotional experience. Because an understanding of emotion affects social behavior, it is critical to the development of social competence. Children’s understanding of emotions is primitive in infancy but develops rapidly over the course of childhood.

Identifying the Emotions of Others

The first step in the development of emotional knowledge is the recognition of different emotions in others. By 3 months of age, infants can distinguish facial expressions of happiness, surprise, and anger (Grossmann, 2010; Serrano, Iglesias, & Loeches, 1993; Walker-Andrews & Dickson, 1997). If, for example, 3- or 4-month-olds are habituated to pictures of happy faces and then are presented with a picture of a face depicting surprise, they dishabituate, showing renewed interest by looking longer at the new picture. By 7 months of age, infants appear to discriminate a number of additional expressions such as fear, sadness, and interest (Grossmann, 2010). For example, 7-month-olds exhibit different patterns of brain waves when they observe fearful and angry facial expressions, a finding that suggests some ability to discriminate these emotions (Kobiella et al., 2008).

417

By this age or a bit earlier, infants also start to perceive others’ emotional expressions as meaningful. For example, if infants at this age are shown a video in which a person’s facial expression and voice are consistent in their emotional expression (e.g., a smiling face and a bubbly voice) and a video in which a person’s facial expression and voice are emotionally discrepant (e.g., a sad face and a bubbly voice), they will attend more to the presentation that is emotionally consistent (Walker-Andrews & Dickson, 1997). Infants much younger than 7 months generally do not seem to notice the difference between the two presentations.

social referencing  the use of a parent’s or other adult’s facial expression or vocal cues to decide how to deal with novel, ambiguous, or possibly threatening situations

the use of a parent’s or other adult’s facial expression or vocal cues to decide how to deal with novel, ambiguous, or possibly threatening situations

As discussed in Chapter 5, at about 5½ months of age, some children begin to demonstrate that they can relate facial expressions of emotion and emotional tones of voice to events in the environment, although this ability is often not seen until 7 to 12 months of age (Saarni et al., 2006; Vaillant-Molina & Bahrick, 2012). Such skills are evident in children’s social referencing—that is, their use of a parent’s or other adult’s facial expression or vocal cues to decide how to deal with novel, ambiguous, or possibly threatening situations. In laboratory studies of this phenomenon, infants are typically exposed to novel people or toys while their mother, at the experimenter’s direction, shows a happy, fearful, or neutral facial expression. In studies of this type, 12-month-olds tend to stay near their mother when she shows fear; to move toward the novel person or object if she expresses positive emotion; and to move partway toward the person or object if she shows no emotion (L. J. Carver & Vaccaro, 2007; Moses et al., 2001; Saarni et al., 2006). Similar results have been found in research on 12-month-olds’ ability to read their mother’s tone of voice. When prevented from seeing their mother’s face as they were being presented with novel toys, infants were more cautious and exhibited more fear when the mother’s voice was fearful than when it was neutral (Mumme, Fernald, & Herrera, 1996).

By 14 months of age, the emotion-related information obtained through social referencing has an effect on children’s touching of the object even an hour later (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004). Children seem to be better at social referencing if they receive both vocal and facial cues of emotion from the adult, and vocal cues seem to be more effective than just visual cues (Vaish & Striano, 2004; Valliant-Molina & Bahrick, 2012).

By the age of 3, children in laboratory studies demonstrate a rudimentary ability to label a fairly narrow range of emotional expressions displayed in pictures or on puppets’ faces (Bullock & Russell, 1985; Denham, 1986; J. A. Russell & Bullock, 1986). Young children—even 2-year-olds—are skilled at labeling happiness (usually by pointing to pictures of faces that reflect happiness; Michalson & Lewis, 1985). The ability to label anger, fear, and sadness emerges and increases in the next year or two, with the ability to label surprise and disgust gradually appearing in the late preschool and early school years (N. Eisenberg, Murphy, & Shepard, 1997; J. A. Russell & Widen, 2002; Widen & Russell, 2003, 2010a). Most children cannot label more complex emotions such as pride, shame, and guilt until early to mid-elementary school (Saarni et al., 2006), but the scope and accuracy of emotion labeling improve thereafter into adolescence (Montirosso et al., 2010).

The ability to discriminate and label different emotions helps children to respond appropriately to their own and others’ emotions. If a child understands that he or she is experiencing guilt, for example, the child may understand the need to make amends to diminish the guilt. Similarly, a child who can see that a peer is angry can devise ways to avoid or appease that peer. In fact, children who are more skilled than their peers at labeling and interpreting others’ emotions are also higher in social competence (Denham et al., 2003; R. S. Feldman, Philippot, & Custrini, 1991; Izard et al., 2008) and lower in behavior problems or social withdrawal (Alonso-Alberca et al., 2012; Fine et al., 2003; Schultz et al., 2001).

418

Understanding the Causes and Dynamics of Emotion

Knowing the causes of emotions is also important for understanding one’s own and others’ behavior and motives (Saarni et al., 2006). It likewise is key for regulating one’s own behavior and, hence, for social competence (Denham et al., 2003; Izard et al., 2008; Schultz et al., 2001). Consider, for example, a child who is being rebuffed or insulted by a friend whom the child has just bested in a game or on an exam. If the child understands that, in this situation, the friend may be lashing out not because the friend is nasty but because the friend feels threatened and inadequate, the child may be much better able to control his or her own response.

A variety of studies have shown rapid development over the preschool and school years in children’s understanding of the kinds of emotions that certain situations tend to evoke in others. In a typical study of this understanding, children are told short stories about characters in situations such as having a birthday party or losing a pet. Children are then asked how the character in the story feels. By age 3, children are quite good at identifying situations that make people feel happy. At age 4, they are fairly accurate at identifying situations that make people sad (Borke, 1971; Denham & Couchoud, 1990), and by age 5, they can identify situations likely to elicit anger, fear, or surprise (N. Eisenberg et al., 1997; Widen & Russell, 2010b).

Children’s ability to understand the circumstances that evoke complex social emotions such as pride, guilt, shame, embarrassment, and jealousy often emerges after age 7, and, according to cross-cultural research that involved children from both Western nations and a remote Himalayan village, this ability is considerable by late elementary school and early adolescence (P. L. Harris et al., 1987; Widen & Russell, 2010b; Wiggers & van Lieshout, 1985). From age 4 until at least age 10, children are generally better at identifying emotions from stories depicting the cause of an emotion than from pictures of facial expressions such as fear, disgust, embarrassment, and shame (an exception is for surprise) (Widen & Russell, 2010a). This is probably because facial expressions of emotions such as anger, fear, sadness, and disgust are often interpreted as indicating more than one emotion (Widen & Naab, 2012).

Another way to assess children’s understanding of the causes of emotions is to record what they say about emotions in their everyday conversations and to ask them to discuss and explain others’ emotions. In this kind of research, even 28-month-olds mention emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, fear, crying, and hurting in appropriate ways in their conversations (e.g., “You sad, Daddy?” or “Don’t be mad.”) and sometimes even mention their causes (e.g., “Santa will be happy if I pee in the potty.” or “Grandma mad. I wrote on wall.”) (Bretherton & Beeghly, 1982).

419

By age 4 to 6, children can give accurate explanations for why their peers expressed negative emotions in their preschool (e.g., because they were teased or lost the use of a toy) (Fabes et al., 1988). Children get more skilled at explaining the causes of emotion across the preschool and school years (Fabes et al., 1991; Sayfan & Lagattuta, 2009; Strayer, 1986). For example, 3rd- and 6th-graders are more likely than kindergartners to believe that someone caught being dishonest will be scared (Barden et al., 1980).

With age, children also come to understand that people can feel particular emotions brought on by reminders of past events. For instance, in one study, 3- to 5-year-olds were told stories about children who experienced a negative event and later saw reminders of that event. One story was about a girl named Mary who has a pet rabbit that lives in a typical rabbit cage. One day Mary’s rabbit is chased away by a dog and is never seen again. In different versions of the story, Mary later sees one of three reminders of her loss—the culprit dog, her rabbit’s cage, or a photograph of her rabbit. At this point, the children were told that Mary started to feel sad and were asked “Why did Mary start to feel sad right now?” On stories such as these, 39% of 3-year-olds, 83% of 4-year-olds, and 100% of 5-year-olds understood that the story characters were sad because a memory cue had made them think about a previous unhappy event (Lagattuta, Wellman, & Flavell, 1997). Similarly, from ages 3 to 5, children increasingly can explain that when people are in a situation that reminds them of a past negative event, they may worry and change their behavior to avoid future negative events (Lagattuta, 2007). Understanding that memory cues can trigger emotions associated with past events helps children to explain their own and others’ emotional reactions in situations that in themselves seem emotionally neutral.

In the elementary school years, children become increasingly sophisticated in their understanding about how, when, and why emotions occur. For example, they become more aware of cognitive processes related to regulating emotion and of the fact that emotional intensity wanes over time. They also come to recognize that people can experience more than one emotion at the same time, including both positive and negative emotions arising from the same source (P. L. Harris, 2006; Harter & Buddin, 1987; F. Pons & Harris, 2005). In addition, they increasingly understand how the mind can be used to both increase and reduce fears and that thinking positively can improve one’s emotion while thinking negatively can worsen it (Bamford & Lagattuta, 2012; Sayfan & Lagattuta, 2009). At around age 10, children begin to understand emotional ambivalence and realize that people can have mixed feelings about events, others, and themselves (Donaldson & Westerman, 1986; Reissland, 1985). Taken together, these developments allow children to better understand the complexities of emotional experience in context.

Children’s Understanding of Real and False Emotions

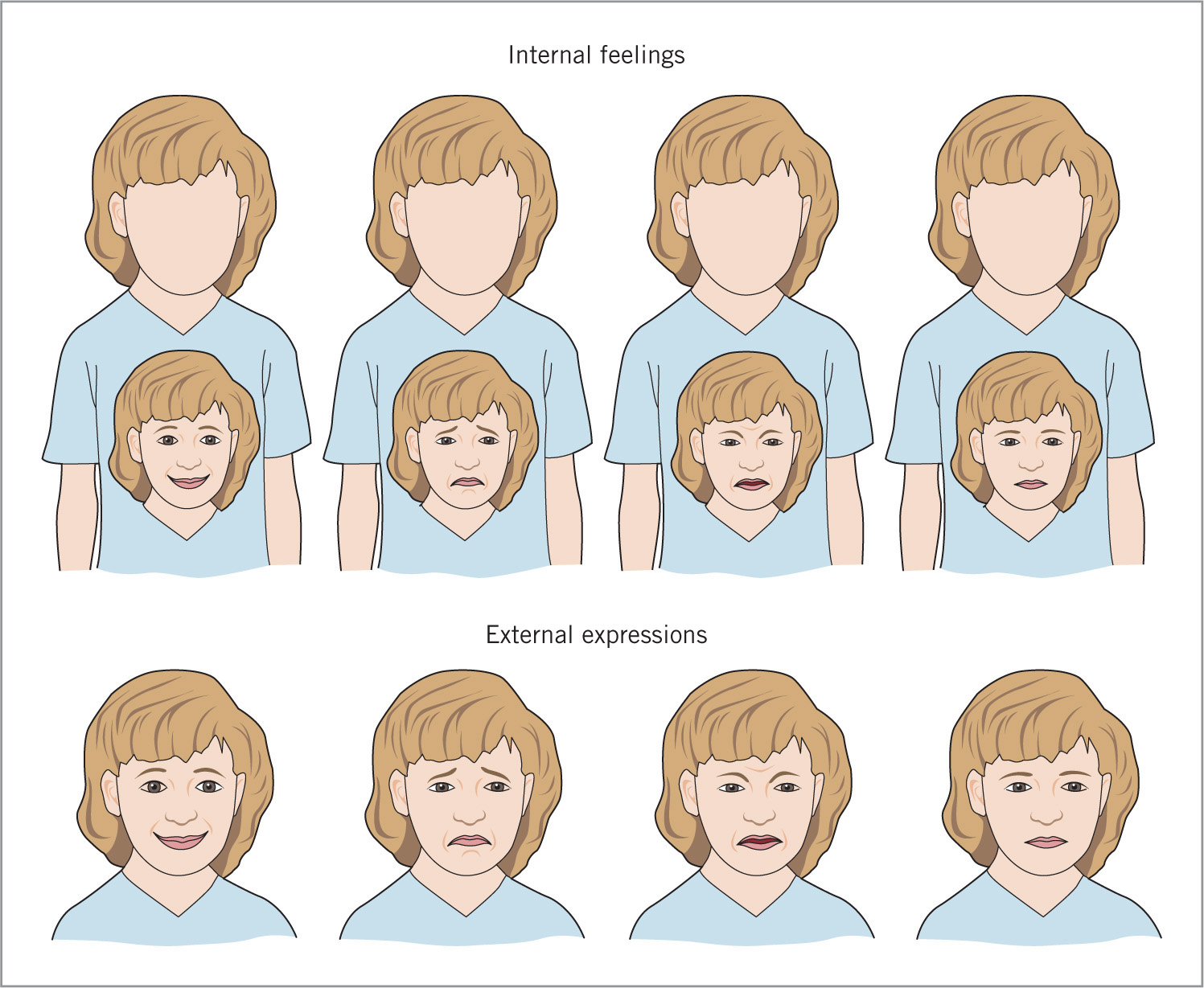

An important component in the development of emotional understanding is the realization that the emotions people express do not necessarily reflect their true feelings (Figure 10.4). The beginnings of this realization are seen in 3-year-olds’ occasional (and usually transparent) attempts to mask their negative emotions when they receive a disappointing gift or prize (P. M. Cole, 1986). By age 5, children’s understanding of false emotion has improved considerably, as demonstrated in a study that used six stories such as the following:

Michelle is sleeping over at her cousin Johnny’s house today. Michelle forgot her favorite teddy bear at home. Michelle is really sad that she forgot her teddy bear. But, she doesn’t want Johnny to see how sad she is because Johnny will call her a baby. So, Michelle tries to hide how she feels.

420

(M. Banerjee, 1997)

After children were questioned to ensure that they understood the story, they were presented with illustrations of various emotional expressions and given instructions such as “Show me the picture for how Michelle really feels” and “Show me the picture for how Michelle will try to look on her face.” Whereas about half of 3- and 4-year-olds chose the appropriate pictures on four or more of the stories, more than 80% of 5-year-olds chose correctly. Studies with both Japanese and Western children also confirm that between 4 and 6 years of age, children increasingly understand that people can be misled by others’ facial expressions (D. Gardner et al., 1988; D. Gross & Harris, 1988).

display rules  a social group’s informal norms about when, where, and how much one should show emotions and when and where displays of emotion should be suppressed or masked by displays of other emotions

a social group’s informal norms about when, where, and how much one should show emotions and when and where displays of emotion should be suppressed or masked by displays of other emotions

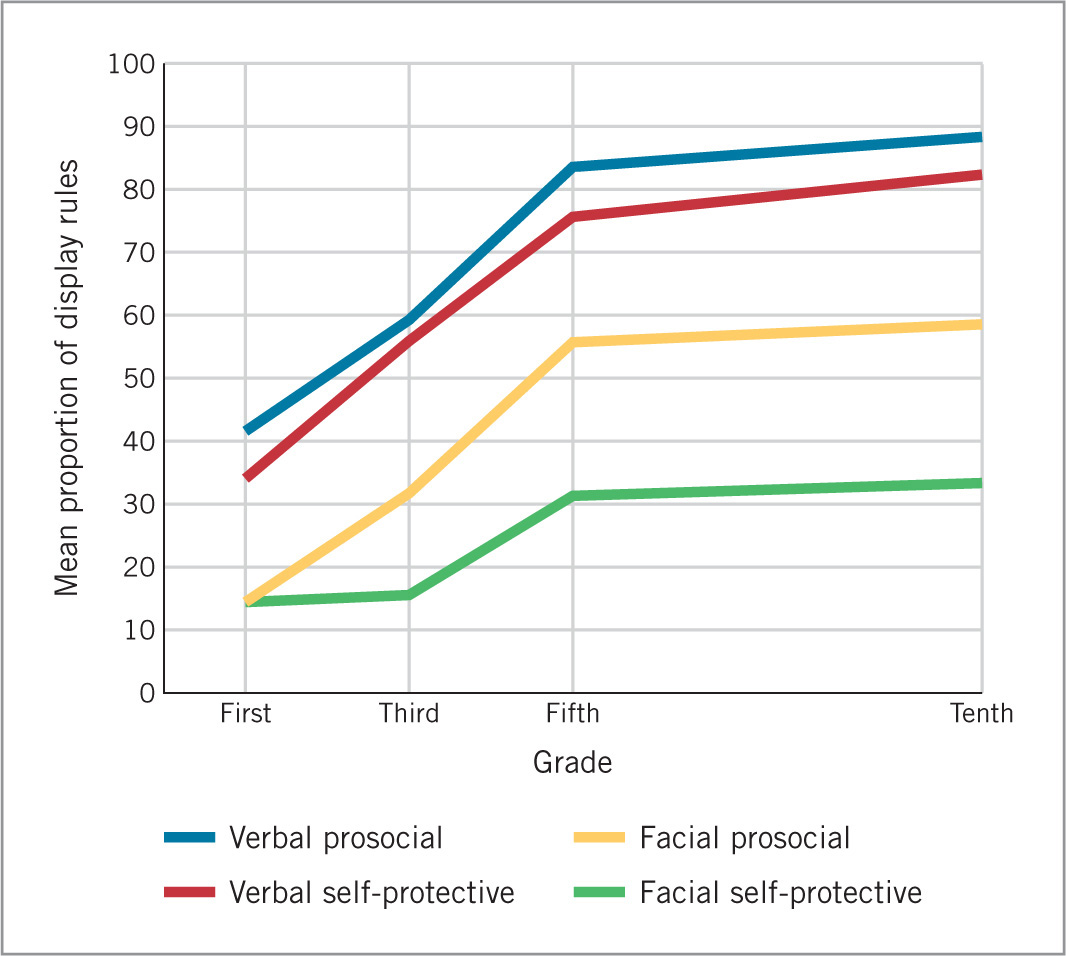

Part of the improvement in understanding false emotion involves a growing understanding of display rules—a social group’s informal norms about when, where, and how much one should show emotions and when and where displays of emotion should be suppressed or masked. Over the preschool and elementary school years, children develop a more refined understanding of when and why display rules are used (M. Banerjee, 1997; Rotenberg & Eisenberg, 1997; Saarni, 1979). They increasingly understand, for example, that people use verbal and facial display rules to protect others’ feelings or their own, as when they pretend to like someone’s cooking so as not to hurt the cook’s feelings (labeled a prosocial motive) or hide their emotions when they themselves are being teased or lose a contest (labeled a self-protective motive) (Gnepp & Hess, 1986). (Figure 10.5 shows age-related changes in these types of motives.) With age, children also better understand that people tend to break eye contact and avert their gaze when lying, and they are increasingly able to use this knowledge to conceal their own deception (McCarthy & Lee, 2009).

421

These age-related advances in children’s understanding of real versus false emotion and display rules are apparently linked to increases in children’s cognitive capacities (Flavell, 1986; P. L. Harris, 2000). However, social factors also seem to affect children’s understanding of display rules. For example, in most cultures, display rules are somewhat different for males and females and reflect societal beliefs about how males and females should feel and behave (Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006; van Beek, van Dolderen, & Demon Dubas, 2006). Elementary school girls in the United States, for instance, are more likely than boys to feel that openly expressing emotions such as pain is acceptable (Zeman & Garber, 1996). In most cultures, girls are also somewhat more attuned than boys to the need to inhibit emotional displays that might hurt others’ feelings (P. M. Cole, 1986; Saarni, 1984). This is especially true for girls from cultures such as India, in which females are expected to be deferential and to express only socially appropriate emotions (M. S. Joshi & MacLean, 1994). These findings obviously are consistent with the gender stereotypes that girls are more likely both to try to protect others’ feelings and to be more emotional than boys.

Parents’ beliefs and behaviors—which often reflect cultural beliefs—likely contribute to children’s understanding and use of display rules (Friedlmeier et al., 2011). As discussed earlier, the emphasis placed on controlling emotional displays in Nepal varies by subculture. Correspondingly, the degree to which Nepali children report masking negative emotions varies with the degree to which mothers in different Nepali subcultures report teaching their children how to manage emotions (P. M. Cole & Tamang, 1998). Thus, children seem to be attuned to display rules that are valued in their culture or that serve an important function in the family.

review:

Children’s understanding of emotions plays an important role in their emotional functioning. Although infants can detect differences in various emotional expressions such as happiness and surprise by 3 to 7 months of age, it is not until they are about 6 months of age that they start to treat others’ emotional expressions as meaningful. At about 5½ to 12 months of age, children begin to connect facial expressions of emotion or an emotional tone of voice with other events in the situation, as evidenced by their use of social referencing. By age 3, children demonstrate a rudimentary ability to label facial expressions and understand simple situations that are likely to cause happiness.

422

As children move through the preschool and elementary school years, their understanding of emotions and situations that cause emotions grows in range and complexity. In addition, they increasingly appreciate that the emotions people show may not reflect their true feelings.