Ethnic Identity

ethnic identity  individuals’ sense of belonging to an ethnic or racial group, including the degree to which they associate their thinking, perceptions, feelings, and behavior with membership in that group

individuals’ sense of belonging to an ethnic or racial group, including the degree to which they associate their thinking, perceptions, feelings, and behavior with membership in that group

The development of identity can present special challenges for minority-group adolescents because it often involves complications related to ethnicity and/or race. In certain contexts, a legitimate distinction can be drawn between the concept of ethnicity (which refers to shared cultural traditions) (M. B. Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990) and the concept of race (which refers to a shared biological ancestry). In the context of identity formation, however, the two concepts are, for practical purposes, quite similar. Thus, for the present discussion, we will use the term ethnic identity to refer to the degree to which an individual has a sense of belonging to an ethnic or racial group and associates his or her thinking, feelings, and behavior with membership in that ethnic or racial group (Rotheram & Phinney, 1987).

450

Ethnic Identity in Childhood

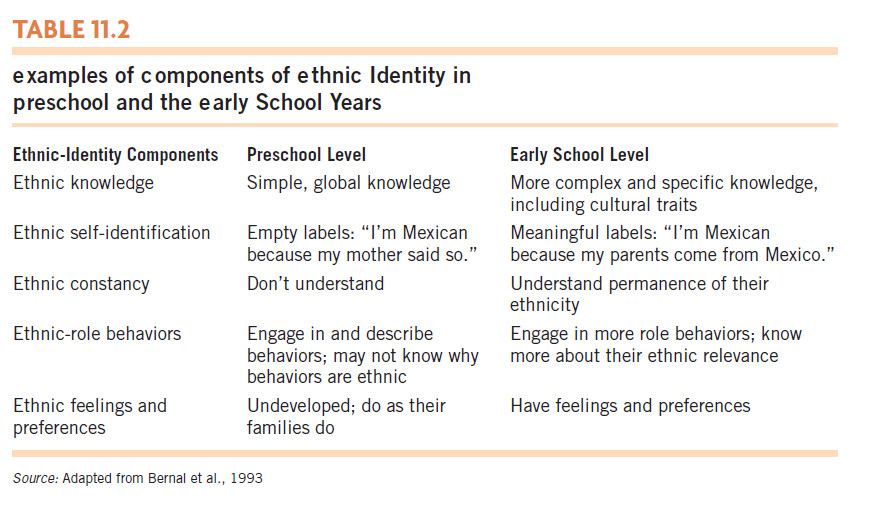

Children’s ethnic identity can be viewed as having five components (Bernal et al., 1993):

Ethnic knowledge. Children’s knowledge that their ethnic group has certain distinguishing characteristics—behaviors, traits, values, customs, styles, and language—that set it apart from other groups.

Ethnic knowledge. Children’s knowledge that their ethnic group has certain distinguishing characteristics—behaviors, traits, values, customs, styles, and language—that set it apart from other groups.

Ethnic self-identification. Children’s categorization of themselves as members of their ethnic group.

Ethnic self-identification. Children’s categorization of themselves as members of their ethnic group.

Ethnic constancy. Children’s understanding that the distinguishing characteristics of their ethnic group do not change across time and place and that they themselves will always be a member of their ethnic group.

Ethnic constancy. Children’s understanding that the distinguishing characteristics of their ethnic group do not change across time and place and that they themselves will always be a member of their ethnic group.

Ethnic-role behaviors. Children’s engagement in the behaviors that reflect the distinguishing characteristics of their ethnic group.

Ethnic-role behaviors. Children’s engagement in the behaviors that reflect the distinguishing characteristics of their ethnic group.

Ethnic feelings and preferences. Children’s feelings about belonging to their ethnic group and their preferences for the group’s members and the characteristics that distinguish the group.

Ethnic feelings and preferences. Children’s feelings about belonging to their ethnic group and their preferences for the group’s members and the characteristics that distinguish the group.

Ethnic identity develops gradually during childhood, although it does not develop for all ethnic-minority children. Preschool children do not really understand the significance of being a member of an ethnic group, although they may be able to label themselves as “Mexican,” “Native American,” “African American,” or the like. Even if they engage in behaviors that characterize their ethnic group and have some simple knowledge about the group, they do not understand that ethnicity is a lasting feature of the self (Bernal et al., 1993) (see Table 11.2).

451

By the early school years, ethnic-minority children know the common characteristics of their ethnic group, start to have feelings about being members of the group, and may have begun to form ethnically based preferences regarding foods, traditional holiday activities, language use, and so forth (Ocampo, Bernal, & Knight, 1993). Children tend to identify themselves according to their ethnic group between the ages of 5 and 8 and shortly thereafter begin to understand that their race or ethnicity is an unchanging feature of themselves (Bernal et al., 1990; Ocampo, Knight, & Bernal, 1997). By late elementary school, minority children in the United States often have a very positive view of their ethnic group (D. Hughes, Way, & Rivas-Drake, 2011).

The family and the larger social environment play a major role in the development of children’s ethnic identity. Parents and other family members and adults can be instrumental in teaching their children about the strengths and unique features of their ethnic culture and instilling them with ethnic pride (A. B. Evans et al., 2012; Hughes et al., 2006; Vera & Quintana, 2004). Such instruction can be especially important for the development of a positive ethnic identity when the child’s racial or ethnic group is the object of prejudice and discrimination in the larger society (Gaylord-Harden, Burrows, & Cunningham, 2012; M. B. Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990).

Ethnic Identity in Adolescence

The issue of ethnic or racial identity often becomes more central in adolescence, as young people try to forge their overall identity (S. E. French et al., 2006). Minority-group members in particular may be faced with difficult and painful decisions as they try to decide the degree to which they will adopt the values of their ethnic group or those of the dominant culture (Phinney, 1993; M. B. Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990).

One difficulty for ethnic-minority adolescents is that they are more likely than they were at younger ages to be aware of discrimination against their group and consequently may feel ambivalent about the group and their own ethnic status (M. L. Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; Seaton et al., 2008; Szalacha et al., 2003). Ethnic-minority children may also be faced with basic conflicts between the values of their ethnic group and those of the dominant culture (Parke & Buriel, 2006; Qin, 2009). For example, many ethnic groups place a premium on family obligation, including values and behaviors related to children’s assisting, supporting, and respecting members of the nuclear and extended family. Thus, adolescents in traditional Mexican American families, for instance, may be expected to spend after-school time helping take care of elderly or young family members or earning money for the family. At the same time, the majority culture may be urging them to participate in school-related activities—such as sports, clubs, or study groups—that can lead to expanded opportunities.

Extending the work of Erikson, Jean Phinney (Phinney & Kohatsu, 1997) has identified three phases of ethnic-identity development that minority youth often experience:

Ethnic-identity diffusion/foreclosure. In this phase, many ethnic-minority adolescents have not examined their ethnicity and are not particularly interested in it. Some others have internalized the majority society’s negative views of their ethnic group.

Ethnic-identity diffusion/foreclosure. In this phase, many ethnic-minority adolescents have not examined their ethnicity and are not particularly interested in it. Some others have internalized the majority society’s negative views of their ethnic group.

Ethnic-identity search/moratorium. Minority youth in this phase develop an interest in learning about their ethnic or racial culture and begin to consider the effects that their ethnicity may have on their life in the present and future. In some cases, this exploration eventually leads to the third phase, ethnic-identity achievement (K. A. Whitehead et al., 2009).

Ethnic-identity search/moratorium. Minority youth in this phase develop an interest in learning about their ethnic or racial culture and begin to consider the effects that their ethnicity may have on their life in the present and future. In some cases, this exploration eventually leads to the third phase, ethnic-identity achievement (K. A. Whitehead et al., 2009).

Ethnic-identity achievement. This phase is characterized by a more conscious awareness of, and commitment to, one’s ethnic group and ethnic identity (M. B. Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990).

Ethnic-identity achievement. This phase is characterized by a more conscious awareness of, and commitment to, one’s ethnic group and ethnic identity (M. B. Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990).

Research suggests that higher levels of ethnic identity are generally associated with high self-esteem, well-being, and low levels of emotional and behavior problems (Berkel et al., 2009; M. D. Jones & Galliher, 2007; Kiang et al., 2006; Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012). For example, advances in African American adolescents’ racial identity have been associated with a decline in their symptoms of depression (Mandara et al., 2009), and adolescents with a positive ethnic identity appear to be buffered from the negative effects of discrimination (Gaylord-Harden et al., 2012; Tynes et al., 2012). The benefits of high ethnic identification appear to hold more consistently for African American and Latino youth than for Asian American youth (Umaña-Taylor, 2011).

Most ethnic-minority adolescents either have stable ethnic identities or progress through the sequence of ethnic-identity development outlined above (Meeus, 2011; Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). The exploration of ethnic identity does not always follow this pattern, however. For some ethnic-minority adolescents, an identity search leads to an exploration of majority identities and a lessening of commitment to the ethnic group. Establishing a clear ethnic identification may be more difficult and less consistent for some adolescents, such as multiethnic youth, who could develop identifications with more than one ethnic or racial group (Marks et al., 2011; Nishina et al., 2010). However, when ethnic-minority parents actively socialize their children into their ethnic culture through teaching about the culture and instilling pride, children tend to have a more positive ethnic identity (Neblett et al., 2012; Umaña-Taylor, Bhanot, & Shin, 2006; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010) and are less susceptible to the negative effects of discrimination (Harris-Britt et al., 2007; Neblett et al., 2008; M. -T. Wang & Huguley, 2012).

453

In some cases, ethnic-minority youth develop a bicultural identity that includes a comfortable identification with both the majority culture and their own ethnic culture. Although trying to straddle two cultures can be stressful, it is not always so, and for some minority youths it can provide certain benefits, such as positive perceptions of opportunities in the majority society (Fuligni, Yip, & Tseng, 2002; Kiang & Harter, 2008; Kiang, Yip, & Fuligni, 2008; LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993). However, for adolescents in some traditional cultures (e.g., Canadian First Nations), a bicultural identity can be associated with lower levels of some strengths that are part of successful identity development, such as certain traditional values, as well as fidelity (loyalty and commitment) and wisdom (Gfellner & Armstrong, 2012).

review:

The development of identity may be especially complicated for many ethnic-minority youth because it involves incorporating ideas and feelings about their ethnicity and/or race. The development of an ethnic identity begins in childhood and involves acquiring knowledge about one’s ethnic group, identifying oneself as a member of that group, developing an understanding of ethnic constancy, engaging in ethnic-role behaviors, and developing feelings and preferences with regard to belonging to one’s ethnic group. Family and community influence these aspects of development.

The achievement of an identity during adolescence can be difficult and painful for minority youth due to their awareness of prejudice against their group. Possible clashes between the values and goals of the group and those of the majority culture can further complicate the process. In adolescence, some minority youth start to actively explore the meaning of their ethnicity and its role in their identity. As a result of this exploration, some adolescents embrace their ethnicity; others gravitate toward the majority culture; and still others identify with both cultures.