Sexual Identity or Orientation

sexual orientation  a person’s preference in regard to males or females as objects of erotic feelings

a person’s preference in regard to males or females as objects of erotic feelings

In childhood and especially adolescence, an individual’s identity includes his or her sexual orientation—that is, a person’s preference in regard to erotic feelings toward males or females. The majority of youth are attracted to individuals of the other sex; a sizable minority is not. Dealing with new feelings of sexuality can be a difficult experience for any adolescent, but the issue of establishing a sexual identity is much harder for some adolescents than for others.

The Origins of Youths’ Sexual Identity

Puberty, during which there are large rises in gonadal hormones (Buchanan, Eccles, & Becker, 1992; C. T. Halpern, Udry, & Suchindran, 1997), is the most likely time for youth to begin experiencing feelings of sexual attraction to others. Most current theorists believe that whether those feelings are inspired by members of the other sex or one’s own is based primarily on biological factors, although the environment may also be a contributing factor (Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2004). Twin and adoption studies, as well as DNA studies, indicate that a person’s sexual orientation is at least partly hereditary: identical twins, for example, are more likely to exhibit similar sexual orientations than are fraternal twins (J. Bailey & Pillard, 1991; J. Bailey et al., 1993; Hamer et al., 1993).

454

Sexual Identity in Sexual-Minority Youth

sexual-minority youth  young people who experience same-sex attractions

young people who experience same-sex attractions

For the majority of youth everywhere, the question of personal sexual orientation never arises, at least at a conscious level. They feel themselves to be unquestioningly heterosexual. For a minority of youth, however, the question of personal sexual identity is a vital one that, initially at least, is often confusing and painful. These are the sexual-minority youth, who experience same-sex attractions.

It is difficult to know precisely how many youths are in this category. Although current estimates indicate that only 2% to 4% of high school students in the United States identify themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007), the number of youths with same-sex attractions is considerably larger because many sexual-minority youth do not identify themselves as such until early adulthood or later (Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007). It is true that, growing up, sexual-minority youth often feel “different” (a difference possibly reflected in their frequently being labeled sissies or tomboys) (Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2007), and some even display cross-gender behavior—for example, in regard to preferences for toys, clothes, or leisure activities—from a relatively early age (Drummond et al., 2008). However, it sometimes takes them a long time to recognize that they are lesbian, gay, or bisexual.

Another complicating fact is that, especially for females, there is considerable instability in adolescents’ and young adults’ reports of same-sex attraction or sexual behavior (Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007). By college age, for example, a notable number of young women identify themselves as “mostly straight”—that is, mostly heterosexual but somewhat attracted to females (E. M. Thompson & Morgan, 2008). One longitudinal study that followed 79 lesbian, bisexual, and unlabeled (those with some same-sex involvement who were unwilling to attach a label to their sexuality) women aged 18 to 25 found that, over a 10-year period, two-thirds changed the identity labels they had claimed at the beginning of the study and one-third changed labels two or more times (L. M. Diamond, 2008). Overall, females are more likely to describe themselves as bisexual or “mostly heterosexual” than are males (Saewyc, 2011). Male youth who have engaged in same-sex sexual experiences show an increasing preference for males from adolescence to early adulthood (Smiler et al., 2011).

In most ways, sexual-minority children and adolescents are developmentally indistinguishable from their heterosexual peers: they deal with many of the same family and identity issues in adolescence and generally function just as well. However, they do face some special challenges. Because being gay, lesbian, or bisexual is viewed negatively by many members of society, it is often difficult for sexual-minority youth to recognize or accept their own sexual preferences. It is usually even more difficult for them to reveal their sexual identity to others—that is, to “come out.” However, with the media’s increasing attention to, and positive portrayals of, sexual-minority people, as well as increasing legal and cultural acceptance of sexual minorities, more sexual-minority youths in the United States are coming out today than did any previous cohort (Savin-Williams, 2005).

The Process of Coming Out

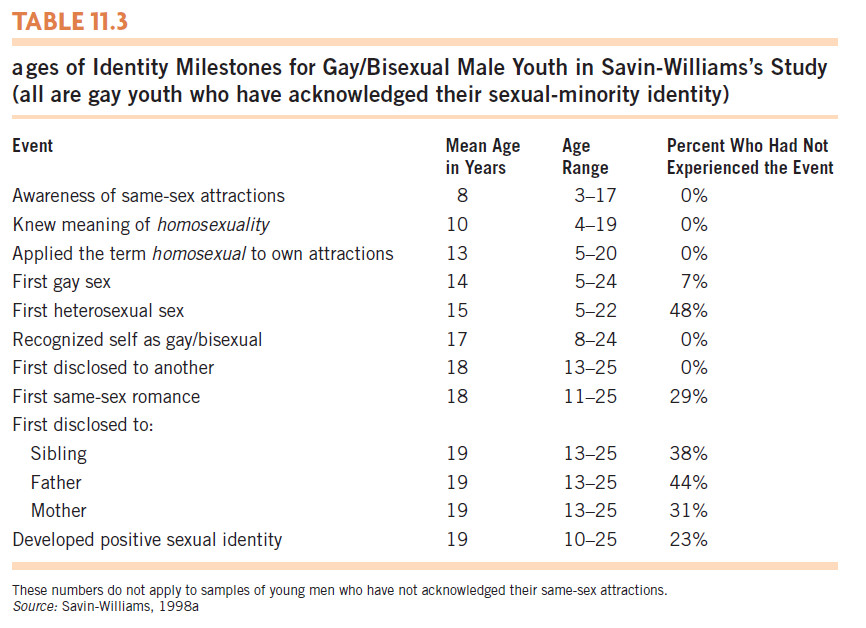

In many cases, the coming-out process for sexual-minority youth involves several developmental phases, some of which occur in varying sequences. It begins with the first recognition—an initial realization that one is somewhat different from others, accompanied by feelings of alienation from oneself and others. At this point, there generally is some awareness that same-sex attractions may be the relevant issue, but the individual does not reveal this to others. A number of sexual-minority youth have some awareness of their sexual attractions by middle childhood (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000; see Table 11.3). As one gay male reported:

455

Maybe it was the third grade and there was an ad in the paper about an all-male cast for a movie. This confused me but fascinated—intrigued—me, so I asked the librarian and she looked all flustered, even mortified, and mumbled that I ought to ask my parents.

(Quoted in Savin-Williams, 1998a, p. 24)

However, there is great variability in the age at which same-sex attractions are first noticed. In one recent study of a large sample of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults, researchers differentiated three age groups for initial recognition of same-sex attraction (Calzo et al., 2011). The largest group, labeled the early-onset group (75% of the sample), reported, on average, that their first same-sex attraction was at about 12 to 14 years of age, with roughly 30% of this group reporting initial same-sex attractions at 7 or 8 years of age. The second largest group, labeled the middle group (19% of the sample), reported that their first same-sex attraction occurred in late adolescence. The third group, labeled the late-onset group (6% of the sample), reported same-sex attractions beginning at an average age of 29 years for men and 34 years for women. Women were much more likely than men to be in the middle and late-onset groups, and within each of these onset groups, women reported somewhat later onset of same-sex attractions. In all three groups, the initial same-sex attractions reported by bisexuals occurred about 1 or 2 years later than those reported by gay and lesbian individuals.

The length of time between recognition of same-sex attractions and self-identification as gay, lesbian, or bisexual varies. For the early-onset group in the study just mentioned, the identification typically occurred about 4 years after the initial recognition of same-sex attractions; for the other two groups, it occurred between 5 and 8 years after initial recognition (see Table 11.3).

456

Sometimes self-identification as gay, lesbian, or bisexual does not occur until after the individual has engaged in same-sex sexual activities. During this period, referred to as test and exploration, the individual may feel ambivalent about his or her same-sex attractions but eventually has limited sexual contact with gays or lesbians and starts to feel alienated from heterosexuality (Savin-Williams, 1998a). This contact may eventually lead to identity acceptance, which is marked by a preference for social and sexual interaction with other sexual-minority individuals and the person’s coming to feel more positive about his or her sexual identity and disclosing it for the first time to heterosexuals (e.g., family or friends). (As noted, this latter stage, which involves self-identification, sometimes precedes sexual exploration.)

Evidence regarding the sequencing of self-identification as a sexual-minority member and the commencement of same-sex sexual activity is mixed. The majority of individuals in all three groups in the above study self-identified prior to engaging in same-sex sexual activities. However, in a large study of gay men, same-sex sexual encounters were more likely to precede self-identification as gay (M. S. Friedman et al., 2008). Moreover, for many gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth and young adults, especially females, heterosexual activities occur prior to, or overlapping with, same-sex activities (L. M. Diamond, Savin-Williams, & Dube, 1999), which might affect the age of self-identification.

The final step for some youth and adults is identity integration, in which gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals firmly view themselves as such, feel pride in themselves and their particular sexual community, and publicly come out to many people. Often, arrival at this milestone is accompanied by anger over society’s prejudice against members of sexual minorities (Savin-Williams, 1996; Sophie, 1986).

Of course, not all individuals go through all these steps or go through them in the same order; some never fully accept their own sexuality or discuss it with others. Others—about one-third in one study—are “discovered” by their parents and do not disclose their sexual identity by choice (Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001).

Consequences of Coming Out

For the most part, sexual-minority youth typically do not disclose their same-sex preferences until late adolescence or a few years later (see Table 11.3; Calzo et al., 2011; M. S. Friedman et al., 2008), with only a minority revealing their sexual orientation before the age of 19 (D’Augelli & Hershberger, 1993; Herdt & Boxer, 1993; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). When they do come out, sexual-minority youths usually disclose their same-sex preferences to a best friend (typically a sexual-minority friend), to a peer to whom they are attracted, or to a sibling, and they do not tell their parents until a year or more later, if at all (Savin-Williams, 1998b). If they do reveal their sexual identity to their parents, they usually tell their mothers before telling their fathers, often because the mother asked or because they wanted to share that aspect of their life with their mother (Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003a).

If sexual-minority youths are from communities or religious or ethnic backgrounds that are relatively low in acceptance of same-sex attractions, they are less likely than other sexual-minority youth to disclose their sexual preference to family members. For example, there is some evidence that non-White families in the United States, including Latino and Asian American families, are less accepting of same-sex attractions than are European American families (Dube et al., 2001). The effects of such low cultural acceptance are reflected in this statement from a young Asian American man:

457

I am first generation from Southeast Asia. I am still very culturally bound and my…mother can’t fathom homosexuality, and many of our friends are the same. So I can’t express myself to my culture or to my family. It probably delayed my coming out. I wish I could have done it in high school like other kids.

(Quoted in Savin-Williams, 1998a, pp. 216–217)

Although many parents react in a supportive or only slightly negative manner to their children’s coming out, there is good reason for many sexual-minority youth to fear disclosing their sexual identity to their family. It is not unusual for parents to initially respond to such a disclosure with anger, disappointment, and especially denial (Heatherington & Lavner, 2008; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003a). Surveys indicate that a substantial portion of sexual-minority youth experience threats or insults from relatives when they reveal their sexual orientation, and a small percent experience physical violence (Berrill, 1990; D’Augelli, 1998). Sexual-minority youth who disclose their sexual identity at a relatively early age, and those who are publicly open about their sexual identity, are often subjected to abuse in the home or community (Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995). As might be expected, sexual-minority youth whose parents are accepting of their child’s sexual orientation report higher self-esteem and lower levels of depression and anxiety (Floyd et al., 1999; Savin-Williams, 1989a, b).

Fear of being harassed or rejected outside the home is one reason many sexual-minority youth hide their sexual identity from heterosexual peers. In fact, many heterosexual adolescents are unaccepting of same-sex preferences in their peers (Bos et al., 2008; L. M. Diamond & Lucas, 2004; Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995) and many sexual-minority youth report that having sexual-minority friends is important in providing social support and acceptance (Savin-Williams, 1994, 1998a).

For a variety of reasons, sexual-minority youth are vulnerable to a number of social and psychological problems. They are prone to experience negative affect, depression, low self-esteem, and low feelings of control in their romantic relationships (Bos et al., 2008; Coker, Austin, & Schuster, 2010; L. M. Diamond & Lucas, 2004). They also report higher levels of school-related problems and substance abuse than do other youth (Bos et al., 2008; Marshal et al., 2008). They are also more likely to be homeless or involved in street life, frequently because they have run away from, or been kicked out of, their home (Coker et al., 2010). Finally, sexual-minority youth have higher reported rates of attempted suicide than do their heterosexual peers (D’Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington, 2001; M. S. Friedman et al., 2011; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003b).

Some of these problems appear to be at least partly due to factors we have already noted, including poor relationships with, and sometimes physical abuse from, family members (Bos et al., 2008; M. S. Friedman et al., 2011; Ryan, 2009), along with victimization and harassment by peers and others in the community (Coker et al., 2010; M. S. Friedman et al., 2011; Martin-Storey & Crosnoe, 2012; Toomey et al., 2010). Additional contributing factors range from sexual abuse in childhood (M. S. Friedman et al., 2011) and discrimination (e.g., bullying from peers) (Saewyc, 2011) to a heightened tendency to engage in behaviors that pose a health threat (e.g., substance use, eating disorders, and, among those who are sexually active, unprotected sex) (Busseri et al., 2008; Coker et al., 2010; Savin-Williams, 2006). Thus, it is likely that what contributes to these social and psychological problems can be attributed to the consequences of being in the sexual minority rather than to same-sex attraction in itself.

It must be noted, however, that the seemingly high rates of problems experienced by sexual-minority youth may be misrepresentative because they are often derived from studies of youth who openly identify themselves as gay and who therefore, as mentioned earlier, are at increased risk of abuse or rejection by their family or community. In fact, estimates of suicide and other problems of adjustment are considerably lower in samples representative of sexual-minority youth overall (Savin-Williams, 2008) and in samples of youth who are attracted to same-sex individuals but have not yet identified themselves as gay (Savin-Williams, 2001a). Moreover, it is important to realize that, despite increased exposure to discrimination, abuses, and victimization, most sexual-minority youth achieve levels of adjustment similar to those of their heterosexual peers (Saewyc, 2011).

458

review:

Although in most respects, sexual-minority youths differ little from their peers, they may face special challenges in regard to their identity and disclosing their same-sex preferences to others. Typically, but not always, they move through the milestones of first recognition, test and exploration, identity acceptance (the order of the second and third milestones varies), and identity integration. Most sexual-minority youth have a sense of their sexual attractions by late adolescence, although some individuals report that they first experienced same-sex attractions in middle childhood or as late as their 30s. Because many sexual-minority youth initially have difficulty accepting their sexuality and fear revealing their sexual identity to others, they often do not tell others about their sexual preferences until mid-to-late adolescence or older.

Parents sometimes have difficulty accepting their children’s same-sex orientation, and a minority of parents abuse or reject their children for this reason. Although sexual-minority youth usually come out first to a friend, they often fear harassment from peers. Perhaps because of the pressures associated with adjusting to their sexual identity, sexual-minority youth who have openly identified themselves as such to others appear to be more likely than other youth to attempt suicide, to be depressed, and to engage in risky behavior.