Self-Esteem

self-esteem  one’s overall evaluation of the worth of the self and the feelings that this evaluation engenders

one’s overall evaluation of the worth of the self and the feelings that this evaluation engenders

A key element of self-concept is self-esteem, or one’s overall evaluation of the self and the feelings engendered by that evaluation (Crocker, 2001). Self-esteem is important because it is related to how satisfied people are with their lives and their overall outlook. Individuals with high self-esteem tend to feel good about themselves and hopeful in general, whereas individuals with low self-esteem tend to feel worthless and hopeless (Harter, 1999). In particular, low self-esteem in childhood and adolescence is associated with problems such as aggression, depression, substance abuse, social withdrawal, suicidal ideation (Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2008; Donnellan et al., 2005; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009; Sowislo & Orth, 2013), and cyberbullying (Modecki, Barber, & Vernon, 2013; S. J. Yang et al., 2013).

Low self-esteem also predicts certain problems in adulthood, including mental health problems, substance abuse and dependence, criminal behavior, weak economic prospects, and low levels of satisfaction with life and with relationships (Boden et al., 2008; Orth, Robins, & Roberts 2008; Trzesniewski et al., 2006). However, it is not entirely clear if low self-esteem actually causes such problems or if both are due to a third factor. For instance, low self-esteem in children is often associated with their parents’ having such characteristics as low education, low income, and teenage maternity, as well as a history of alcohol or illicit drug use and criminal behavior. It may be that these parental characteristics, perhaps partly based on heredity, underlie both the children’s low self-esteem and their high rates of behavioral and psychological problems (Boden et al., 2008).

It should also be noted that high self-esteem, especially if not based on positive self-attributes, may have costs for children and youths (K. Lee & Lee, 2012). For example, high self-esteem in aggressive children is associated with their increasingly valuing the rewards that they derive from their aggression and their belittlement of victims (Menon et al., 2007). The combination of high self-esteem and narcissism—grandiose views of the self, inflated feelings of superiority and entitlement, and exploitative interpersonal attitudes—has been associated with especially high levels of aggression in young adolescents (Thomaes et al., 2008).

459

Sources of Self-Esteem

A number of factors are related to the development of children’s self-esteem. These include their genetic inheritance, the quality of their relationships with others, their appearance and competence, their school and neighborhood, and various cultural factors that impinge on their lives. In addition, how children think about themselves in a wide variety of contexts contributes to their feelings of overall self-worth. Thus, the development of self-esteem offers a highly transparent example of the interaction of nature and nurture, including the sociocultural context. Moreover, it is a domain of functioning marked by large individual differences.

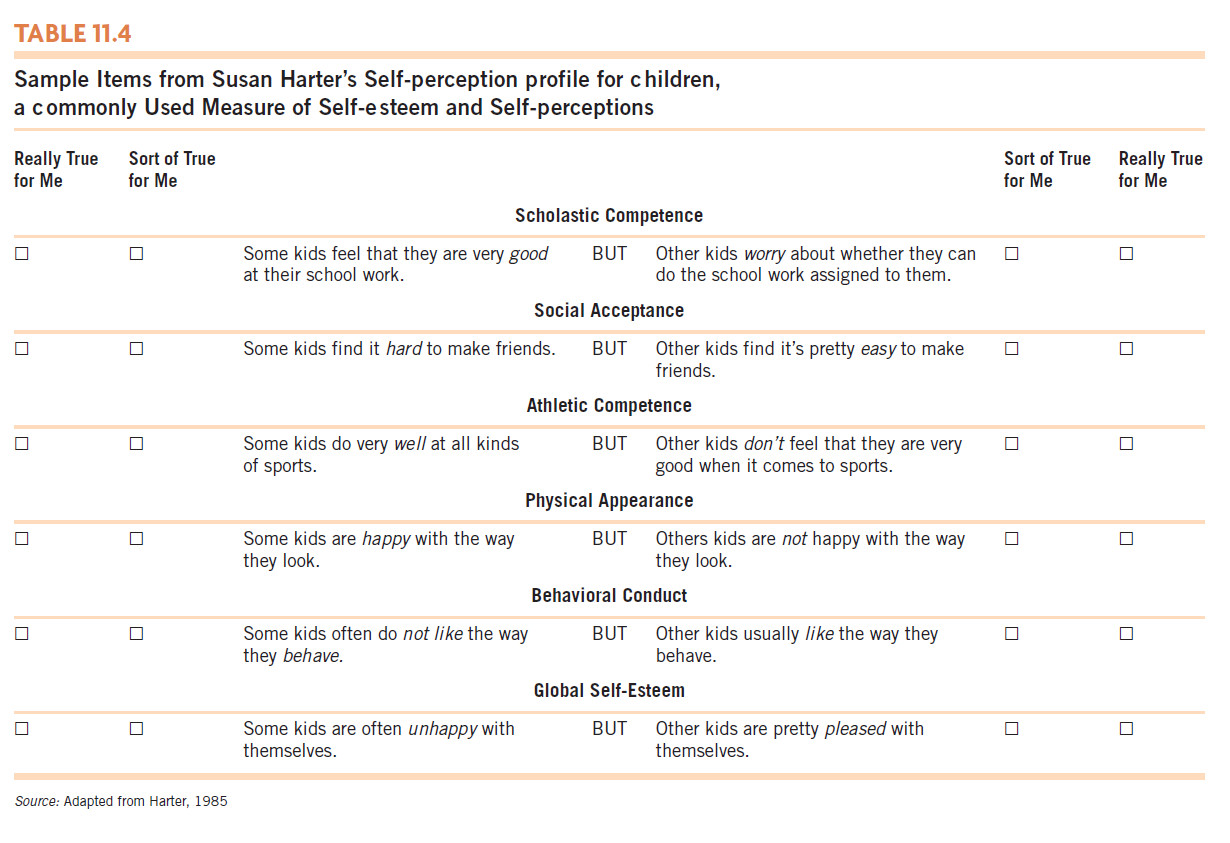

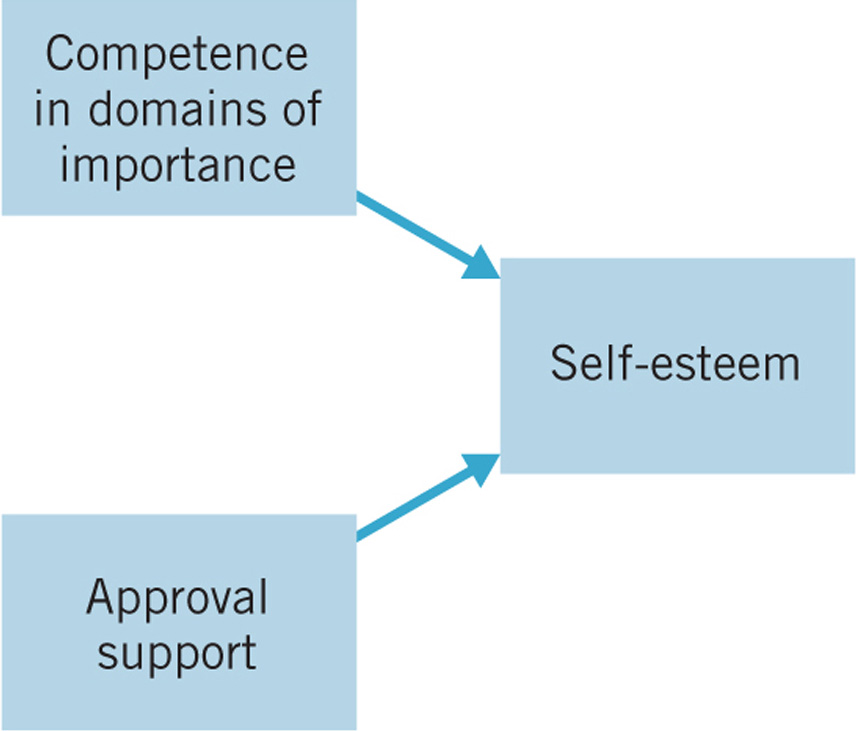

To measure children’s self-esteem, researchers ask children, verbally or by questionnaire, about their perceptions of themselves. As reflected in Table 11.4, the questions assess children’s sense of their own physical attractiveness, athletic competence, social acceptance, scholastic ability, and the appropriateness of their behavior. In addition, the researchers ask children about their global self-esteem—how they feel about themselves in general.

460

Heredity

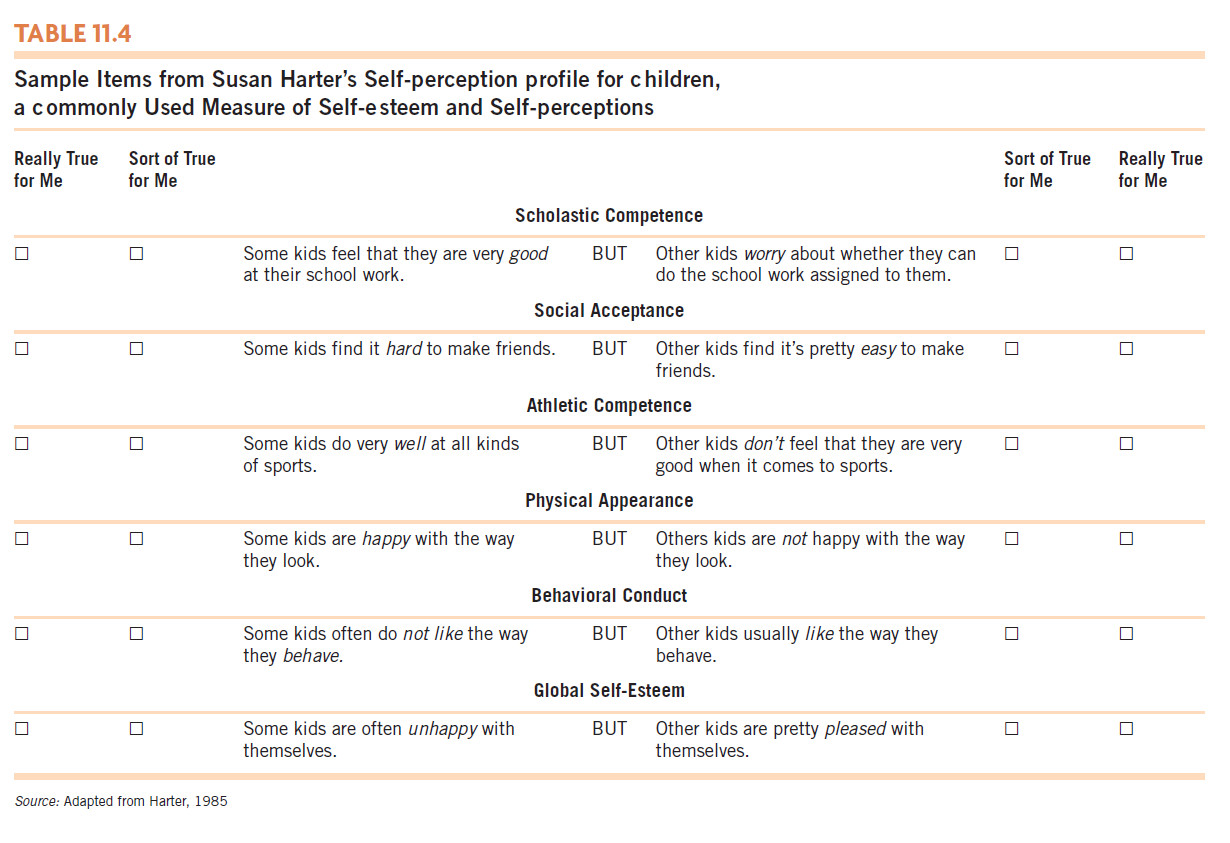

Heredity contributes to children’s sense of self-worth in several ways. The most obvious of these involve physical appearance and athletic ability, both of which are strongly related to self-esteem. In childhood and adolescence, attractive individuals are much more likely to report high self-esteem than are those who are less attractive (Erkut et al., 1998; Harter, 2012), possibly because attractive people are viewed more positively by others and are treated better than unattractive people. Perhaps as a consequence, attractive people behave in more socially competent ways and are well-adjusted, which likely enhances their appeal to others (Langlois et al., 2000). The association between self-esteem and attractiveness may be stronger for girls than for boys, particularly in late childhood and adolescence, because girls are much more likely to report concerns about their appearance (see Figure 11.3). This gender difference may partly explain why boys report slightly higher self-esteem than do girls, especially in late adolescence (Kling et al., 1999).

In addition, genetically based intellectual abilities and aspects of personality, such as sociability, no doubt play a part in academic and social self-esteem (Harter, 1983; E. A. Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Connell, 1998), although self-esteem may also affect academic competence (X. Chen, He, & Li, 2004). The hereditary contribution to self-esteem is underscored by the fact that on a variety of dimensions, self-esteem is more similar in identical twins than in fraternal twins and in nontwin siblings than in stepsiblings (McGuire et al., 1994).

Interestingly, the genetic contribution to self-esteem appears to be stronger for boys than for girls (Raevuori et al., 2007), perhaps, in part, because of the power and pervasiveness of certain environmental influences on girls’ self-esteem. Chief among these are the social norms and media messages regarding the importance of female beauty (Harter, 2012). A telling example of this is the emphasis that the media and peers put on the desirability of thinness, an emphasis that appears to contribute to some girls’ dissatisfaction with their bodies and themselves by the age of 8 (Dohnt & Tiggemann, 2006).

Others’ Contributions to Self-Esteem

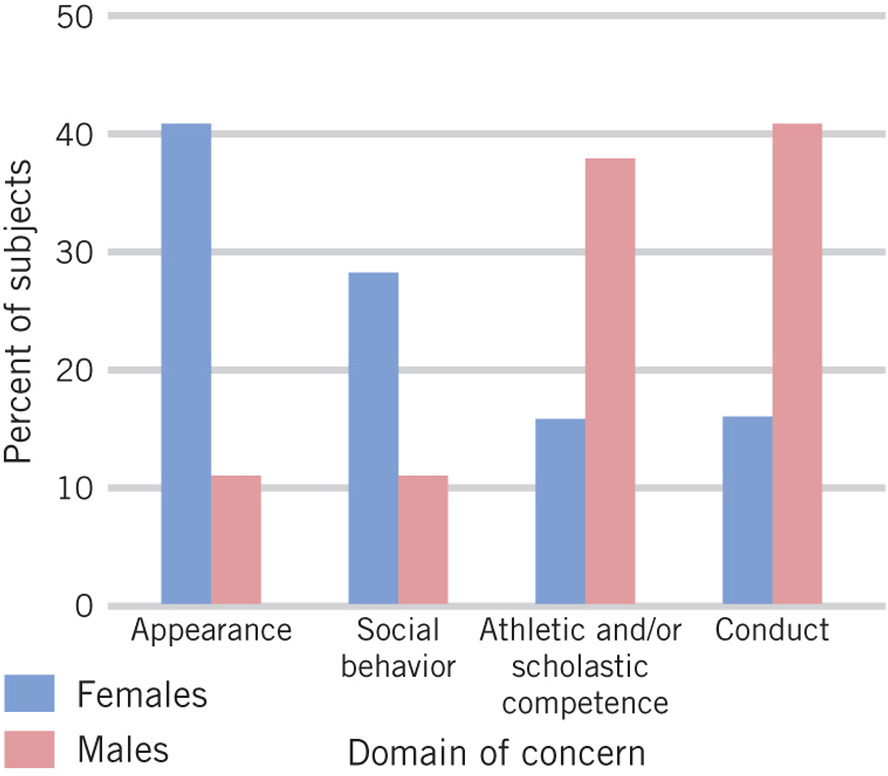

One of the most important influences on children’s self-esteem is the approval and support they receive from others. This idea goes back more than a century to Charles Cooley’s (1902) proposal of the “looking glass self,” the concept that people’s self-esteem is a reflection of what others think of them (see Figure 11.4). More specifically, Cooley maintained that we develop our sense of self-esteem by internalizing the views that important others have of us.

Similar ideas were proposed by Erikson (1950) and Bowlby (1969), who argued that children’s sense of self is grounded in the quality of their relationships with others. If children feel loved when young, they come to believe that they are lovable and worthy of others’ love; if they feel unloved when young, they come to believe the opposite. This view is supported by links between attachment status and children’s self-esteem or positive self-perceptions (Boden et al., 2008; Cassidy et al., 2003; Verschueren, Marcoen, & Schoefs, 1996). Moreover, parents who tend to be accepting and involved with their children and who use supportive yet firm child-rearing practices tend to have children and adolescents with high self-esteem (Awong, Grusec, & Sorenson, 2008; Behnke et al., 2011; S. M. Cooper & McLoyd, 2011; Lamborn et al., 1991). Support from nonparental adults such as teachers has likewise been associated with higher self-esteem in adolescents (Sterrett et al., 2011). In contrast, parents who regularly react to their children’s unacceptable behavior with belittlement or rejection—in effect, condemning the child rather than the behavior—are likely to instill in their children a sense of worthlessness and of being loved only to the extent that they meet parental standards (Harter, 1999, 2006; Heaven & Ciarrochi, 2008).

461

Over the course of childhood, children’s self-esteem is increasingly affected by peer acceptance (Harter, 1999). Indeed, in late childhood, children’s feelings of competence about their appearance, athletic ability, and likability may be affected more by their peers’ evaluations than by their parents’. This tendency to evaluate the self on the basis of peers’ perceptions has been associated with a preoccupation with approval, fluctuations in self-esteem, lower levels of peer approval, and lower self-esteem (Harter, 2012). At the same time, children’s self-esteem likely affects how peers respond to them. Youth who see themselves as competent in their peer relationships tend to be well liked (M. S. Caldwell et al., 2004), perhaps because their behavior is confident and socially engaging.

In contrast to children, adolescents increasingly evaluate themselves on the basis of their own internalized standards rather than on the approval of others (Connell & Wellborn, 1991; Higgins, 1991). Adolescent girls’ self-esteem, for example, is increasingly linked to their feeling that they can have relationship authenticity—that is, that they can be themselves in terms of their thoughts and feelings in their social interactions (Impett et al., 2008). Experts agree that adolescents who continue to base their self-evaluations on others’ standards and approval are at risk for psychological problems, at least in Western industrialized cultures where an autonomous, relatively stable sense of self is valued (Damon & Hart, 1988; Harter, 2012; Higgins, 1991).

School and Neighborhood

Children’s and adolescents’ self-esteem can also be affected by their school and neighborhood environments. The effect of the school environment is most apparent in the decline in self-esteem that is associated with the transition from elementary school to junior high (Eccles et al., 1989). The junior high environment often is not a good developmental match for 11- and 12-year-olds because many children of that age are distressed by the switch from having one teacher whom they know well and who is well acquainted with their skills and weaknesses to having many teachers who know little about them. In addition, the transition to junior high forces students to enter a new group of peers and to go from the top of one school’s pecking order to the bottom of another’s. Especially in poor, overcrowded, urban schools, young adolescents often do not receive the attention, support, and friendship they need to do well and to feel good about themselves (Seidman et al., 1994; Wigfield et al., 2006).

That children’s self-esteem can be affected by their neighborhood is suggested by the evidence that living in poverty in an urban environment, especially in violent neighborhoods, is associated with lower self-esteem among adolescents in the United States (Behnke et al., 2011; Ewart & Suchday, 2002; Paschall & Hubbard, 1998; Turley, 2003). This may be due to high levels of stress that undermine the quality of parenting, prejudice from more affluent peers and adults, and inadequate material and psychological resources (Behnke et al., 2011; K. Walker et al., 1995).

462

Self-Esteem in Minority Children

Minority children in the United States generally are more likely than majority (European American) children to live in “undesirable,” impoverished neighborhoods and to be subjected to prejudice from both adults and peers, which can undermine children’s self-esteem (e.g., M. L. Greene et al., 2006; Seaton & Yip, 2009). Because children’s self-esteem is strongly influenced by the evaluations of others, it often is assumed that minority children, especially African American and Latino children, have lower self-esteem than do European American children.

In fact, this is not always true. Although the self-esteem of young European American children tends to be higher than that of their African American peers, after age 10, the trend reverses slightly. This shift most likely occurs because (1) African Americans tend to identify more with their racial group than do European Americans, and (2) African American culture, more than European American culture, emphasizes desirable aspects of the group’s distinctiveness (as reflected in the popular slogan from the 1960s and 1970s, “Black is beautiful”). Because ethnic identity is an important aspect of self-concept for many African Americans, this emphasis on the positive features of being African American may enhance African American adolescents’ and adults’ self-esteem (Gray-Little & Hafdahl, 2000; Herman, 2004).

Less is known about the self-esteem of Latino and other minority children. Because of the poverty and prejudice that many Latino Americans experience, one might expect their self-esteem to be consistently much lower than that of European Americans at all ages, and it is, at least through elementary school. Beginning in adolescence, however, the difference becomes much smaller (Twenge & Crocker, 2002). In part, this change may be due to the fact that Latino (e.g., Mexican American) parents encourage their children’s identification with the family and with the larger ethnic group (Parke & Buriel, 2006), which can provide a buffer against some of the negative effects that poverty and prejudice often have on self-esteem. Increases in Latino adolescents’ self-esteem are also associated with growth in their exploration of their ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009). Especially in communities where Latinos are in the majority, Latino youth who identify with their ethnic group, in comparison with those who do not, tend to have higher self-esteem (Umaña-Taylor, Diversi, & Fine, 2002).

Other minority groups in the United States show different patterns of self-esteem. Asian American children, for instance, report higher self-esteem in elementary school than do European Americans and African Americans, but by high school their reported self-esteem is lower than that of European Americans (Herman, 2004; Twenge & Crocker, 2002). In fact, in one recent study, Asian Americans were lower in self-esteem by sixth grade (Witherspoon et al., 2009). As we discuss in the next section, cultural factors may contribute to the lower levels of self-esteem reported in some ethnic-minority groups.

Although discrimination can have a negative effect on adolescents’ self-esteem, how minority children and adolescents think about themselves is influenced much more strongly by acceptance from their family, neighbors, and friends than by reactions from strangers and the society at large (Galliher, Jones, & Dahl, 2011; Seaton, Yip, & Sellers, 2009). Thus, minority-group parents can help their children develop high self-esteem and a sense of well-being by instilling them with pride in their culture and by being generally supportive (Bámaca et al., 2005; Berkel et al., 2009; S. M. Cooper & McLoyd, 2011). For example, African American adolescents whose mothers support them and help them cope with problems hold more positive attitudes toward their race and express greater pride in being African American than do adolescents with less supportive mothers. In turn, this greater pride predicts lower levels of perceived stress and, consequently, better adjustment (C. H. Caldwell et al., 2002). Having positive peer and adult role models from their own ethnic group also contributes to children’s positive feelings about themselves and their ethnicity (A. R. Fischer & Shaw, 1999; K. Walker et al., 1995).

463

Culture and Self-Esteem

In various cultures, the sources of self-esteem, as well as its form and function, may be different, and the criteria that children use to evaluate themselves may vary accordingly. Between Asian and Western cultures, for example, there are fundamental differences that appear to affect the very meaning of self-esteem. In Western cultures, it is argued, self-esteem is related to individual accomplishments and self-promotion. In contrast, in Asian societies such as Japan and China, which traditionally have had a collectivist (or group) orientation, self-esteem is believed to be more related to contributing to the welfare of the larger group and affirming the norms of social interdependence. In this cultural context, self-criticism and efforts at self-improvement may be viewed as evidence of commitment to the group (Heine et al., 1999). But in terms of standard measures of self-esteem (i.e., those used by U.S. researchers), this motivation toward self-criticism is reflected as lower self-evaluation (Harter, 2012).

It is not surprising, then, that scores on standard measures of self-esteem vary considerably across these cultures. Except perhaps in the area of social competence, for instance, self-esteem scores tend to be lower in China, Japan, and Korea than in the United States, Canada, Australia, and some parts of Europe (Harter, 1999). These differences seem to be partly due to the greater emphasis that the Asian cultures place on modesty and self-effacement—which results in less positive self-descriptions (Cai et al., 2007; Suzuki, Davis, & Greenfield, 2008; Q. Wang, 2004). Indeed, the fact that European American and African American adolescents tend to be more comfortable with being praised and with events that make them look good and cause them to stand out than are Asian American and Latino adolescents (Suzuki et al., 2008) could affect the degree to which they report high self-esteem, and hence account for the pattern of ethnic differences in self-esteem (Harter, 2012).

464

In addition, in some Asian societies, people tend to be more comfortable acknowledging discrepancies in themselves—for example, the existence of both good and bad personal characteristics—than are people in Western cultures, and this tendency results in reports of lower self-esteem in late adolescence and early adulthood (Hamamura, Heine, & Paulhus, 2008; Spencer-Rodgers et al., 2004). The same types of cultural influences may affect measures of self-esteem in U.S. subcultures that have maintained traditional non-Western ideas about the self and its relation to other people.

review:

Many factors affect children’s and adolescents’ self-esteem. Genetic predispositions, the support and approval of parents and peers, physical attractiveness, academic competence, and social factors such as the neighborhood and school environments all affect how children and youth feel about themselves. Although minority children in the United States often are exposed to prejudice and poverty, supportive families and communities can buffer and even enhance their self-esteem. The sources of self-esteem, as well as its form and function, may differ across cultures, and self-evaluations may differ accordingly.