The Role of Parental Socialization

Socialization is the process through which children acquire the values, standards, skills, knowledge, and behaviors that are regarded as appropriate for their present and future roles in their particular culture. Parents typically contribute to their children’s socialization in at least three different ways (Parke & Buriel, 1998, 2006):

Parents as direct instructors. Parents may directly teach their children skills, rules, and strategies and explicitly inform or advise them on various issues.

Parents as direct instructors. Parents may directly teach their children skills, rules, and strategies and explicitly inform or advise them on various issues. Parents as indirect socializers. Parents provide indirect socialization through their own behaviors with and around their children. For example, in everyday actions, parents unintentionally demonstrate skills, communicate information and rules, and model attitudes and behaviors toward others.

Parents as indirect socializers. Parents provide indirect socialization through their own behaviors with and around their children. For example, in everyday actions, parents unintentionally demonstrate skills, communicate information and rules, and model attitudes and behaviors toward others. Parents as social managers. Parents manage their children’s experiences and social lives, including their exposure to various people, activities, and information, especially when children are young. If parents decide to place their child in day care, for example, the child’s daily experience with peers and adult caregivers will likely differ dramatically from that of children whose daily care is provided at home.

Parents as social managers. Parents manage their children’s experiences and social lives, including their exposure to various people, activities, and information, especially when children are young. If parents decide to place their child in day care, for example, the child’s daily experience with peers and adult caregivers will likely differ dramatically from that of children whose daily care is provided at home.

Parents use all these ways of socializing their children’s behavior and development. However, as you will see, parents differ considerably in how they do so.

Parenting Styles and Practices

parenting styles  parenting behaviors and attitudes that set the emotional climate in regard to parent–child interactions, such as parental responsiveness and demandingness

parenting behaviors and attitudes that set the emotional climate in regard to parent–child interactions, such as parental responsiveness and demandingness

As you undoubtedly recognize from your own experience, parents in different families exhibit quite different parenting styles, that is, parenting behaviors and attitudes that set the emotional climate of parent–child interactions. Some parents, for example, are strict rule setters who expect complete and immediate compliance from their children. Others are more likely to allow their children some leeway in following the standards they have set for them. Still others seem oblivious to what their children do. Parents also differ in the overall emotional tone they bring to their parenting, especially with regard to the warmth and support they convey to their children. In trying to understand the impact that parents can have on children’s development, researchers have identified two dimensions of parenting style that are particularly important: (1) the degree of parental warmth, support, and acceptance, and (2) the degree of parenting control and demandingness (Maccoby & Martin, 1983).

473

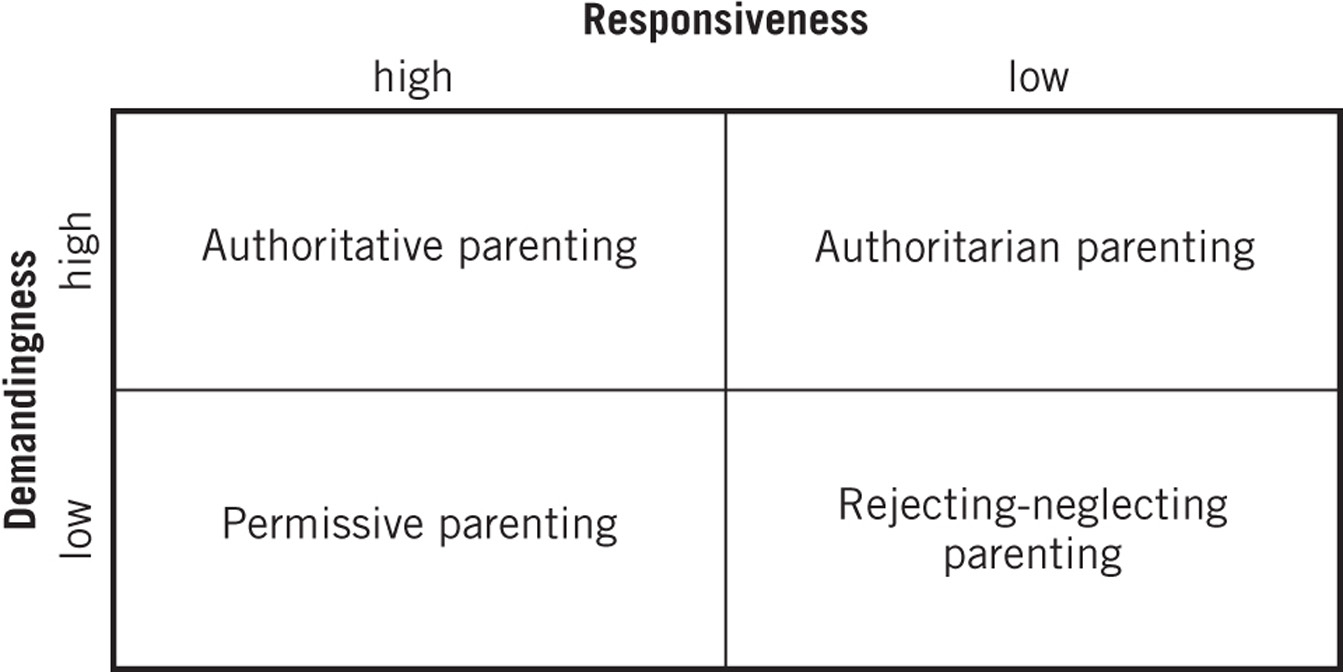

The pioneering research on parenting style was conducted by Diana Baumrind (1973), who differentiated among four styles of parenting related to the dimensions of support and control. These styles are referred to as authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and rejecting-neglecting (Baumrind, 1973, 1991b) (Figure 12.1). The differences in these parenting styles are reflected in the following examples, which depict the way four different mothers respond when they observe their child taking away another child’s toy.

- Authoritative. When Kareem takes away Troy’s toy, Kareem’s mother takes him aside and points out that the toy belongs to Troy and that Kareem has made Troy upset. She also says, “Remember our rule about taking other peoples’ things. Now think about how to make things right with Troy.” Her tone is firm but not hostile, and she waits to see if Kareem returns the toy.

- Authoritarian. When Elene takes Mark’s toy, Elene’s mother comes over, grabs her arm, and says in an angry voice, “Haven’t I warned you about taking other people’s things? Return that toy now or you will not be able to watch TV tonight. I’m tired of you disobeying me!”

- Permissive. When Jeff takes away Angelina’s toy, Jeff’s mother does not intervene. She doesn’t like to discipline her son and usually does not try to control his actions. However, she is not detached as a parent and is affectionate with him in other situations.

- Rejecting-neglecting. When Heather takes away Alonzo’s toy, Heather’s mother, as she does in most situations, pays no attention. She generally is not very involved with her child. Even when Heather behaves well, her mother rarely hugs her or expresses approval of Heather or her behavior.

According to Baumrind, authoritative parents, like Kareem’s mother, tend to be demanding but also warm and responsive. They set clear standards and limits for their children, monitor their children’s behavior, and are firm about enforcing important limits. However, they allow their children considerable autonomy within those limits, are not restrictive or intrusive, and are able to engage in calm conversation and reasoning with their children. They are attentive to their children’s concerns and needs and communicate openly with their children about them. They are also measured and consistent, rather than harsh or arbitrary, in disciplining them. Authoritative parents usually want their children to be socially responsible, assertive, and self-controlled. Baumrind found that children of authoritative parents tend to be competent, self-assured, and popular with peers. They are also able to behave in accordance with adults’ expectations and are low in antisocial behavior. As adolescents, they tend to be relatively high in social and academic competence, self-reliance, and coping skills, and relatively low in drug use and problem behavior (Baumrind, 1991a; Driscoll, Russell, & Crockett, 2008; Hoeve et al., 2011; Lamborn et al., 1991).

474

authoritarian parenting  a parenting style that is high in demandingness and low in responsiveness. Authoritarian parents are nonresponsive to their children’s needs and tend to enforce their demands through the exercise of parental power and the use of threats and punishment. They are oriented toward obedience and authority and expect their children to comply with their demands without question or explanation.

a parenting style that is high in demandingness and low in responsiveness. Authoritarian parents are nonresponsive to their children’s needs and tend to enforce their demands through the exercise of parental power and the use of threats and punishment. They are oriented toward obedience and authority and expect their children to comply with their demands without question or explanation.

Authoritarian parents, much like Elene’s mother, tend to be cold and unresponsive to their children’s needs. They are also high in control and demandingness and expect their children to comply with their demands without question. Authoritarian parents tend to enforce their demands through the exercise of parental power, especially the use of threats and punishment. Children of authoritarian parents tend to be relatively low in social and academic competence, unhappy and unfriendly, and low in self-confidence, with boys being more negatively affected than girls in early childhood (Baumrind, 1991b). High levels of authoritarian parenting are associated with youths’ experiencing negative events at school (e.g., being teased by peers, doing poorly on tests) and ineffective coping with everyday stressors (Zhou et al., 2008), along with depression, aggression, delinquency, and alcohol problems (Bolkan et al., 2010; Driscoll et al., 2008; Kerr, Stattin, & Özdemir, 2012; Rinaldi & Howe, 2012).

permissive parenting  a parenting style that is high in responsiveness but low in demandingness. Permissive parents are responsive to their children’s needs and do not require their children to regulate themselves or act in appropriate or mature ways.

a parenting style that is high in responsiveness but low in demandingness. Permissive parents are responsive to their children’s needs and do not require their children to regulate themselves or act in appropriate or mature ways.

In studies by Baumrind and many others, parents’ control of children’s behavior has been measured mostly in terms of the setting and enforcing of limits. Another type of control is psychological control—control that constrains, invalidates, and manipulates children’s psychological and emotional experience and expression. Examples include parents’ cutting off children when they want to express themselves, threatening to withdraw love and attention if they do not behave as expected, exploiting children’s sense of guilt, belittling their worth, and discounting or misinterpreting their feelings. These kinds of psychological control are more likely to be reported by children in relatively poor families. Their use by parents predicts children’s depression in late middle childhood and adolescence, as well as externalizing problems (e.g., aggression and delinquency) (Barber, 1996; Kuppens et al., 2012; Li, Putallaz, & Su, 2011; Soenens et al., 2008). However, parental use of psychological control may not always be a causal factor in children’s problem behaviors. For example, some adolescents who exhibit high levels of problem behaviors also engage in high levels of conflict with their mothers, which in turn, appears to elicit mothers’ use of psychological control (Steeger & Gondoli, 2013).

Permissive parents are responsive to their children’s needs and wishes and are lenient with them. Like Jeff’s mother, they do not require their children to regulate themselves or act in appropriate ways. Their children tend to be impulsive, lacking in self-control, prone to externalizing problems, and low in school achievement (Baumrind, 1973, 1991a, 1991b; Rinaldi & Howe, 2012). As adolescents, they engage in more school misconduct and drug or alcohol use than do peers with authoritative parents (Driscoll et al., 2008; Lamborn et al., 1991).

rejecting-neglecting parenting  a disengaged parenting style that is low in both responsiveness and demandingness. Rejecting-neglecting parents do not set limits for or monitor their children’s behavior, are not supportive of them, and sometimes are rejecting or neglectful. They tend to be focused on their own needs rather than their children’s needs.

a disengaged parenting style that is low in both responsiveness and demandingness. Rejecting-neglecting parents do not set limits for or monitor their children’s behavior, are not supportive of them, and sometimes are rejecting or neglectful. They tend to be focused on their own needs rather than their children’s needs.

Rejecting-neglecting parents, such as Heather’s mother, are disengaged parents, low in both demandingness and responsiveness to their children. They do not set limits for them or monitor their behavior and are not supportive of them. Sometimes they are rejecting or neglectful of their children altogether. These parents are focused on their own needs rather than their children’s. Children who experience rejecting-neglecting parenting tend to have disturbed attachment relationships when they are infants or toddlers and problems with peer relationships as children (Parke & Buriel, 1998; R. A. Thompson, 1998). In adolescence, they tend to exhibit a wide range of problems, from antisocial behavior and low academic competence to internalizing problems (e.g., depression, social withdrawal), substance abuse, and risky or promiscuous sexual behavior (Baumrind, 1991a, 1991b; Driscoll et al., 2008; Hoeve et al., 2011; Lamborn et al., 1991). The negative effects of this type of parenting appear to continue to accumulate and worsen over the course of adolescence (Steinberg et al., 1994).

475

In addition to the broad effects that different parenting styles seem to have for children, they also establish an emotional climate that affects the impact of whatever specific parenting practices may be employed (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). For example, children are more likely to view punishment as being justified and indicating serious misbehavior when it comes from an authoritative parent than when it comes from a parent who generally is punitive and hostile. Moreover, parenting style affects children’s receptiveness to parents’ practices. Children are more likely to listen to, and care about, their parents’ preferences and demands if their parents are generally supportive and reasonable than if they are distant, neglectful, or expect obedience in all situations (Grusec, Goodnow, & Kuczynski, 2000; M. L. Hoffman, 1983).

Although parenting style appears to have an effect on children’s adjustment, it is important to keep in mind that children’s behavior sometimes shapes parents’ typical parenting style. In a recent study, adolescents’ reports of relatively high levels of externalizing problems (e.g., delinquency, loitering, and intoxication) and internalizing problems (e.g., low self-esteem, depressive symptoms) predicted a decline in parents’ authoritative parenting styles (as reported by the youths) 2 years later, whereas an increase or decline in authoritative parenting over the same 2 years did not predict a change in the adolescents’ adjustment (Kerr et al., 2012). As noted previously, the family is a dynamic system, with each member having an effect on other members.

Ethnic and Cultural Influences on Parenting

In keeping with our theme of the sociocultural context, it is important to note that the effects of different parenting styles and practices may vary somewhat across ethnic or racial groups in the United States. Consider findings regarding restrictive, highly controlling parenting. In contrast to the negative findings for European American children, researchers have found that for African American children, especially those in low-income families, this kind of parenting (e.g., involving intrusiveness or unilaternal decision making) is associated with positive developmental outcomes such as high academic competence and low levels of deviant behavior (Dearing, 2004; Ispa et al., 2004; Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Steinberg, 1996; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008). Moreover, whereas parental use of physical discipline has been associated with high levels of problem behaviors for European American youths, such punishment is associated with relatively low levels for African American youths (Deater-Deckard et al., 1996; Lansford et al., 2004), especially when African American mothers believe measured physical punishment is an appropriate method for correcting misbehavior (McLoyd et al., 2007).

One possible explanation for these findings is that many caring African American parents may feel the need to use authoritarian control to protect their children from special dangers, ranging from the risks found in crime-ridden neighborhoods to the prejudice experienced in predominantly affluent European American communities (Kelley, Sanchez-Hucles, & Walker, 1993; Parke & Buriel, 2006; Smetana, 2011). In turn, African American youth may recognize the protective motive in their parents’ controlling practices and, consequently, respond relatively positively to their parents’ demands. This may be especially true in lower-income African American communities, where controlling, intrusive parenting is more normative than in many middle-class European American communities (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011) and may be interpreted in a benign manner by African American children, especially if their parents are warm in other situations (Ispa et al., 2004; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008).

476

Indeed, particular parenting styles and practices may also have different meanings, and different effects, in different cultures. For example, in European American families, authoritative parenting, as noted, seems to be associated with a close relationship between parent and child and with children’s positive psychological adjustment and academic success. Although a somewhat similar relation between authoritative parenting and adjustment has been found in China, it tends to be weaker (Chang et al., 2004; Cheah et al., 2009; C. A. Nelson, Thomas, & de Haan, 2006; Zhou et al., 2004, 2008). In fact, some features of parenting that are considered appropriate in traditional Chinese culture are more characteristic of authoritarian parenting than of authoritative parenting. Compared with European American mothers, for example, Chinese American mothers are more likely to believe that children owe unquestioning obedience to their parents and thus use scolding, shame, and guilt to control them (Chao, 1994). Although such a pattern of parental control generally fits the category of authoritarian parenting, it appears to have few negative effects for Chinese American and Chinese children, at least prior to adolescence. Rather, for younger Chinese children, it is primarily physical punishment that is related to negative outcomes (N. Eisenberg, Chang et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2004, 2008).

A likely explanation is that in Chinese culture, children (but perhaps not adolescents) view parental strictness and emphasis on obedience as signs of parental involvement and caring, and as important for family harmony (Chao, 1994; Yau & Smetana, 1996). Consistent with this idea, parents’ directiveness with their preschoolers—for example, telling the child what to do—is positively related to parental warmth/acceptance in China, whereas it is negatively related to this dimension in the United States (Wu et al., 2002). However, it is interesting to note that in some urban areas of China today, parental use of control appears to be relatively low compared with that in a number of other cultures (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011), probably as a result of exposure to Western child-rearing values.

Cultural variation in the relation of parental warmth to parental control was highlighted by a study of families in the United States and 12 other countries. In this study, high levels of both warmth and control were found in African American and Hispanic American families, as well as in a number of other cultures in countries such as Italy, Kenya, Sweden, Colombia, Jordan, the Philippines, and Thailand. In contrast, European American families were characterized by moderately high warmth and low control, and these two dimensions of parenting were not correlated with each other. Although it is not clear why high warmth and high control go together in all the different groups mentioned above except European Americans, it is likely related to differences in the degree to which various cultures value high levels of parental control (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011).

Because of variations such as these, findings regarding parenting styles in U.S. families—especially findings that involve primarily European American middle-class families—cannot automatically be generalized to other cultures or subcultures. Rather, the relation of parenting to children’s development must be considered in terms of the cultural context in which it occurs. Nonetheless, it should be noted that there are probably more similarities than differences in the parenting values and behaviors of various ethnic groups in the United States, as is strongly suggested by research that controls for socioeconomic status (e.g., N. E. Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003; Julian, McKenry, & McKelvey, 1994; Whiteside-Mansell et al., 2003).

477

The Child as an Influence on Parenting

Among the strongest influences on parents’ parenting style and practices are the characteristics of their children, such as their appearance, behavior, and attitudes. Thus, individual differences in children contribute to the parenting they receive, which, in turn, contributes to differences among children in their behavior and personalities.

Attractiveness

Although you might not want to think it is true, children’s physical appearance can influence the way their parents respond to them. For example, mothers of very attractive infants are more affectionate and playful with their infants than are mothers of infants with unappealing faces. Moreover, mothers of unappealing infants, compared with mothers of appealing ones, are more likely to report that their infants interfere with their lives (Langlois et al., 1995). Thus, from the first months of life, unattractive infants may experience somewhat different parenting than attractive infants. And this pattern continues throughout childhood, with attractive children tending to elicit more positive responses from adults than unattractive children do (Langlois et al., 2000).

Children’s Behaviors and Temperaments

Children’s influence on parenting through their appearance is, of course, a passive contribution. Consistent with the theme of the active child, children also actively shape the parenting process through their behavior and expressions of temperament. Children who are disobedient, angry, or challenging, for example, make it more difficult for parents to use authoritative parenting than do children who are compliant and positive in their behavior (Cook, Kenny, & Goldstein, 1991; Crouter & Booth, 2003; Kerr et al., 2012).

Differences in children’s behavior with their parents—including the degree to which they are emotionally negative, unregulated, and disobedient—can be due to a number of factors. The most prominent of these are genetic factors related to temperament (Saudino & Wang, 2012). At the same time, studies with twins indicate that environmental factors, likely including social interactions with family members, also affect infants’ and children’s temperament (Rasbash et al., 2011; Roisman & Fraley, 2006; Saudino & Wang, 2012). In addition, there appear to be genetically based differences in how children respond to their environment, including their parents’ caregiving. In line with our discussion of differential susceptibility in Chapter 10, some children may be more reactive to the quality of parenting they receive than are others. For example, children with a difficult temperament often react worse (e.g., have more problems with adjustment or are less socially competent) when they receive nonsupportive or nonoptimal parenting; however, these same children sometimes respond better when they receive supportive parenting (Beach et al., 2012; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011; Pluess & Belsky, 2010).

478

Children’s noncompliance and externalizing problems offer further insight into the complex ways in which children can affect their parents’ behavior toward them. In resisting their parents’ demands, for example, children may become so whiny, aggressive, or hysterical that their parents back down, leading the children to resort to the same behavior to resist future demands (G. R. Patterson, 1982). By adolescence, those youths who are noncompliant and acting out, in part due to their heredity, appear to evoke negativity from their parents to a greater degree than their parents’ negativity affects the youths’ externalizing problems (Marceau et al., 2013).

bidirectionality of parent–child interactions  the idea that parents and their children are mutually affected by one another’s characteristics and behaviors

the idea that parents and their children are mutually affected by one another’s characteristics and behaviors

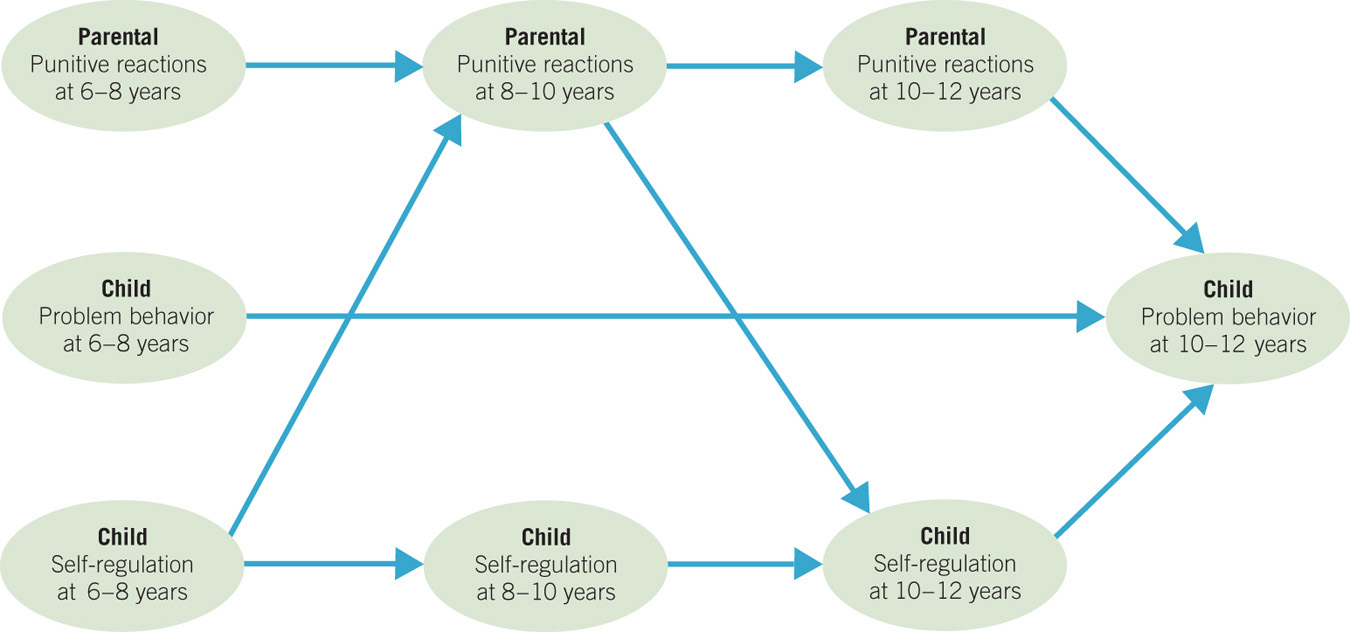

Over time, the mutual influence, or bidirectionality, of parent–child interactions reinforces and perpetuates each party’s behavior (Combs-Ronto et al., 2009; Morelen & Suveg, 2012). One study, for example, found that children’s low self-regulation at age 6 to 8 (which may have been influenced by maternal behaviors at an earlier age) predicted mothers’ punitive reactions (e.g., scolding and rejection) to their children’s expressions of negative emotion at age 8 to 10. In turn, mothers’ punitive reactions when their children were age 8 to 10 predicted low levels of self-regulation in the children at age 10 to 12 (N. Eisenberg, Fabes et al., 1999) (Figure 12.2).

A similar self-reinforcing and escalating negative pattern is common when parents are hostile and inconsistent in enforcing standards of conduct with their adolescent children; their children, in turn, are hostile, insensitive, disruptive, and inflexible with them (Conger & Ge, 1999; Rueter & Conger, 1998) and exhibit increased levels of problem behaviors (Roche et al., 2010; Scaramella et al., 2008). Bidirectional interaction is also a likely key factor in parent–child relationships that exhibit a pattern of cooperation, positive affect, harmonious communication, and coordinated behavior, with the positive behavior of each partner eliciting analogous positive behavior from the other (Aksan, Kochanska, & Ortmann, 2006; Denissen et al., 2009).

479

Socioeconomic Influences on Parenting

Another factor that is associated with parenting styles and practices is socioeconomic status. Parents with low SES are more likely than higher-SES parents to use an authoritarian and punitive child-rearing style; higher-SES parents tend to use a style that is more authoritative, accepting, and democratic (Pinderhughes et al., 2000; D. S. Shaw et al., 2004). Higher-SES mothers, for example, are less likely than low-SES mothers to be controlling, restrictive, and disapproving in their interactions with their young children (Jansen et al., 2012), even in African American families (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2008) and non-Western cultures (X. Chen, Dong, & Zhou, 1997; von der Lippe, 1999). In addition, as discussed in Chapter 6, higher-SES mothers talk more to their children, including about emotion (Garrett-Peters et al., 2008, 2011). They also elicit more talk from their children, and they follow up more directly on what their children say. This greater use of language by higher-SES mothers may foster better communication between parent and child, as well as promote the child’s verbal skills (B. Hart & Risley, 1995; E. Hoff, Laursen, & Tardif, 2002).

Some of the SES differences in parenting style and practices are related to differences in parental beliefs and values (Bornstein & Bradley, 2003; E. A. Skinner, 1985). Higher-SES parents are more likely than lower-SES parents to view themselves as teachers rather than as providers or disciplinarians (S. A. Hill & Sprague, 1999) and to feel more capable as young parents (Jahromi et al., 2012). Both in the United States and in other Western countries, parents from lower-SES families often promote conformity in children’s behavior, whereas higher-SES parents are more likely to want their children to become self-directed and autonomous (Alwin, 1984; Luster, Rhoades, & Haas, 1989).

It is likely that level of education is an important aspect of SES associated with differences in parental values and knowledge. Highly educated parents have more knowledge about parenting (Bornstein et al., 2010) and tend to hold a more complex view of development than do parents with less education. They are more likely, for example, to view children as active participants in their own learning and development (J. Johnson & Martin, 1985; E. A. Skinner, 1985). Such a view may make high-SES parents more inclined to allow children to have a say in matters that involve them, such as family rules and the consequences for breaking them.

It is important to recognize that SES differences in parenting styles and practices may partly reflect differences in the environments in which families live. As we have noted, many low-SES parents may adopt a controlling, authoritarian parenting style to protect their children from harm in poor, unsafe neighborhoods, especially those with high rates of violence and substance abuse. Correspondingly, it may be that higher-SES parents—being less economically stressed and freer of the need to protect their children from violence—have more time and energy to focus on complex issues in child rearing and may be in a better position to adopt an authoritative style, interacting with their children in a controlled yet flexible and stimulating manner (Hoff-Ginsberg & Tardif, 1995).

480

Economic Stress and Parenting

Protracted economic stress is a strong predictor of quality of parenting, familial interactions, and children’s adjustment, and the outcome for each is generally negative (McLoyd, 1998; Valenzuela, 1997). Moreover, economic pressures tend to increase the likelihood of marital conflict and parental depression, which, in turn, make parents more likely to be uninvolved with, or hostile to, their children (Benner & Kim, 2010; Conger et al., 2002; Parke et al., 2004) and less likely to cooperate and support each other’s parenting (L. F. Katz & Low, 2004; Margolin, Gordis, & John, 2001; J. P. McHale et al., 2004). For both children and adolescents, the nonsupportive, inconsistent parenting associated with economic hardship and living in a poor neighborhood correlates with increased risk for depression, loneliness, unregulated behavior, delinquency, academic problems, and substance use (Benner & Kim, 2010; Doan, Fuller-Rowell, & Evans, 2012; Kohen et al., 2008; Scaramella et al., 2008).

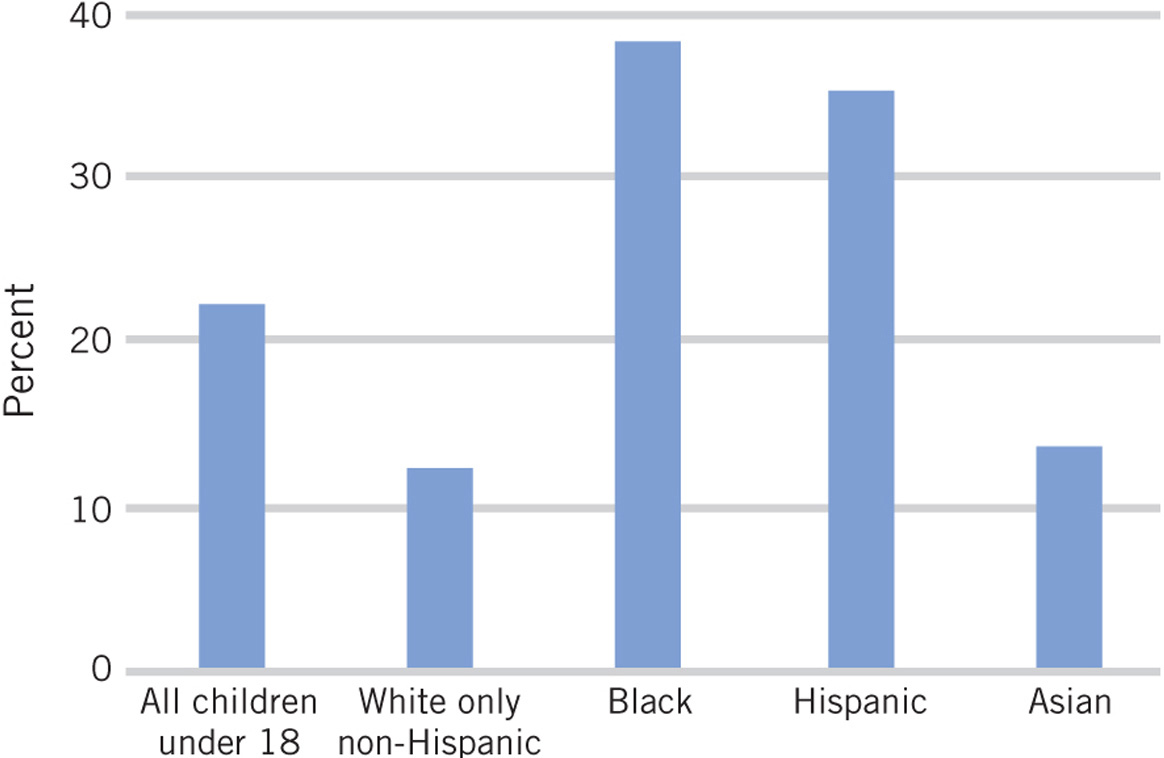

The quality of parenting and family interactions is especially likely to be compromised for families at the poverty level, which in 2010 included 32% of U.S. single-parent families headed by mothers and 6.2% of families headed by married adults. All told, about 22% of children younger than 18 years lived in poverty in the United States in 2010, the highest rate of child poverty among industrialized, Western countries (National Poverty Center, 2013). (As Figure 12.3 shows, minority children are the most likely to be among this population.) At one time or another, a substantial number of families in poverty experience homelessness, which obviously makes effective parenting extremely difficult (see Box 12.2).

One factor that can help moderate the potential impact of economic stress on parenting is having supportive relationships with relatives, friends, neighbors, or others who can provide material assistance, child care, advice, approval, or a sympathetic ear. Such positive connections can help parents feel more successful and satisfied as parents and actually be better parents (C.-Y. Lee et al., 2011; MacPhee et al., 1996; McConnell et al., 2011). Although social support for parents is generally associated with better parental functioning and child outcomes (Cardoso, Padilla, & Sampson, 2010; R. Feldman & Masalha, 2007; R. D. Taylor, Seaton, & Dominguez, 2008), it may be less beneficial for low-income parents in the poorest, most dangerous neighborhoods (Ceballo & McLoyd, 2002) and for depressed parents (R. Taylor, 2011).

In considering the effects of economic stress on parenting, it is important to bear in mind that individuals contribute to their own socioeconomic situation through their traits, dispositions, and goals, and these same traits, dispositions, and goals are likely to influence their relations with their children and their children’s behavior. For example, when investigators took into account adolescents’ initial level of socioeconomic status, they found that youths with personality characteristics that reflected positive social skills, regulation, goal-setting, and hard work were more likely to attain a higher income and educational level at an older age than were youths who lacked those traits; and their children, in turn, exhibited high levels of positive development (Schofield et al., 2011). Similarly, adolescents with lower levels of problem behavior tended, over time, to attain higher socioeconomic status and to be more emotionally invested in their children, and their children, in turn, exhibited fewer problem behaviors (M. J. Martin et al., 2010). Such findings support an interactionist model of socioeconomic influence on human development, in which the association between SES and developmental outcomes reflects both social causation (SES influences developmental outcomes) and social selection (individual characteristics influence SES) (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010).

481

Box 12.2: a closer look

HOMELESSNESS

It is impossible to know the precise number of homeless children and families in the United States, much less in the world. In some countries, such as India and Brazil, the figure is in the millions (Diversi, Filho, & Morelli, 1999; Verma, 1999). In the United States, it is estimated that 3 million people are homeless at some point over the course of a given year, including 1.6 million children (1 in 45), approximately 650,000 of whom are younger than 6. Many homeless children are in the care of at least one parent, most often a single mother (National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty, 2012; United States Conference of Mayors, 2009).

Homeless children are at risk in a variety of ways. At the most basic level, they are often malnourished and lack adequate medical care. Frequently, they are also exposed to the chaotic and unsafe conditions found in many shelters. They are also at increased risk both of being sexually abused (Buckner et al., 1999) and of ending up in foster care (Zlotnick et al., 1998). As might be expected, homeless children’s school performance tends to be poor and is commonly accompanied by absenteeism and serious behavioral problems (Masten et al., 1997; Obradovic´ et al., 2009; Tyler et al., 2003). Exceptions to this pattern tend to include children who have a close relationship with their parents, especially if their parents are involved in their education (Masten & Sesma, 1999; Miliotis et al., 1999), and children who are temperamentally well regulated (Obradovic´, 2010). Compared with poor children who are not homeless, homeless children also experience more internalizing problems, such as depression, social withdrawal, and low self-esteem (Buckner et al., 1999; DiBiase & Waddell, 1995; Rafferty & Shinn, 1991). However, those who are well regulated tend to be better adjusted and to get along better with peers (Obradovic´, 2010).

In adolescence, numerous youths either choose to leave their homes or are kicked out, and many of them live on the streets. Estimates of homeless, runaway, or “thrown away” adolescents in the United States (many of whom may not be included in homeless statistics) range from about 575,000 to more than 1.6 million (e.g., Urbina, 2009). Predictors of youths’ running away include their living in lower-income families and neighborhoods, living in a home without two biological parents, and experiencing peer victimization and school suspension (Tyler & Bersani, 2008; Tyler, Hagewen, & Melander, 2011). In comparison with other adolescents from the same neighborhoods, these homeless youths generally report having experienced more conflict with, and rejection by, their parents and more parental maltreatment, including physical abuse, not infrequently due to their sexual orientation. They also often exhibited problem behaviors when they were at home (Tyler et al., 2011). However, these differences seem to be based in part on differences in the parents’ behavior toward the children or in levels of stress in the home; they do not seem to be due merely to the homeless children’s having had more problems of adjustment (American Psychological Association, 2013; Tyler et al., 2011; Wolfe, Toro, & McCaskill, 1999).

In many third-world countries, homeless children often live with other children on the streets and report doing so because of the loss of their parents or because of sexual, mental, or physical abuse at home (Aptekar & Ciano-Federoff, 1999). In many cases, children living on the streets reside at least part of the time with a parent or other relative (Diversi et al., 1999; Verma, 1999). Some youths report that they stay on the streets in order to enjoy freedom with their friends (J. J. Campos et al., 1994; Sampa, 1997).

Life on the streets in most third-world countries is even riskier than it is in the United States. In one study of Brazilian street youth, 75% were engaged in illegal activities such as stealing and prostitution (J. J. Campos et al., 1994). The longer these children were on the streets, the more likely they were to be involved in illegal activities. Compared with peers who hung out on the street but usually slept in homes, street children also were at greater risk for drug abuse and began sexual activities at a younger age. Thus, it is clear that homelessness, wherever it occurs, takes a tremendous toll on the welfare of children and on the larger society.

482

review:

Styles of parenting are associated with important developmental outcomes. Researchers have delineated four basic parenting styles varying in parental warmth and control: authoritative (relatively high in control and high in warmth); authoritarian (high in control but low in warmth); permissive (high in warmth and low in control); and rejecting-neglecting (low in both warmth and control). Particular styles of parenting can affect the meaning and impact of specific parenting practices, as well as children’s receptiveness to these practices. In addition, the significance and effects of different parenting styles or practices may vary somewhat across cultures.

Education and income are associated with variations in parenting. Economic stressors can undermine the quality of marital interactions and parent–child interactions. Children in poor and homeless families are more at risk for serious adjustment problems, such as depression, academic failure, disruptive behavior at school, and drug use.