Maternal Employment and Child Care

Paralleling many of the other changes that have occurred in the U. S. family over the past half century, the employment rate for mothers has increased more than fourfold. In 1955, only 18% of mothers with children younger than 6 were employed outside the home (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). In 2011, 56% of mothers with infants younger than 1 year, 64% of mothers with children younger than 6, and 76% of mothers with children aged 6 to 17 years old worked outside the home (U.S. Department of Labor, 2013). These changes in the rates of maternal employment reflect a variety of factors, including greater acceptance of mothers who work outside the home, more opportunities in the workplace for women, and increased financial need, often brought about by single motherhood or divorce.

The dramatic rise in the number of mothers working outside the home raised a variety of concerns. Some experts predicted that maternal employment, especially in an infant’s first year, would seriously diminish the quality of maternal caregiving and that the mother–child relationship would suffer accordingly. Others worried that “latchkey” children who were left to their own devices after school would get into serious trouble, academically and socially. Over the past two decades, much research has been devoted to addressing such concerns. For the most part, the findings have been reassuring.

The Effects of Maternal Employment

Taken as a whole, research does not support the idea that maternal employment per se has negative effects on children’s development. There is little consistent evidence, for example, that the quality of mothers’ interactions with their children necessarily diminishes substantially as a result of their employment (Gottfried, Gottfried, & Bathurst, 2002; Huston & Aronson, 2005; Paulson, 1996). Although working mothers typically spend less time with their children than do nonworking mothers, the difference is largely offset by the fact that, compared with nonworking mothers, working mothers spend a greater portion of their child-care time engaged in social interactions with their infants rather than in straightforward caregiving activities (Huston & Aronson, 2005).

Even in the area of greatest debate—the effects of maternal employment on infants in their first year of life—when negative relations between maternal work and children’s cognitive or social behavior have been found, the results have not been consistent across studies, ethnic groups, or the type of analyses applied to the data (L. Berger et al., 2008; Brooks-Gunn, Han, & Waldfogel, 2010; Burchinal & Clarke-Stewart, 2007). For example, some research suggests that early maternal employment is associated with better adjustment at age 7 for children in low-income African American families, whereas no such effect was found for those in a study of low-income Hispanic American families (R. L. Coley & Lombardi, 2013).

499

Overall, what the evidence does suggest is that maternal employment may be associated with negative outcomes for some children under certain circumstances and that it may be associated with positive outcomes in other circumstances. As will be discussed shortly, the quality of child care provided while mothers work is undoubtedly a critical factor affecting whether maternal employment is associated with cognitive, language, or social problems in young children. In addition, if children are not adequately supervised and monitored after school, their academic performance may suffer (Muller, 1995). However, if employed mothers are involved with their children and arrange for their after-school supervision, the children tend to do as well in school as children of mothers who are not employed outside the home (Beyer, 1995).

Studies of maternal employment extending beyond infancy also reveal contextual variation in the effects that maternal employment can have on children’s development. For instance, a study of 3- to 5-year-olds found that those whose mother worked a night shift (starting at 9:00 p.m. or later) tended to exhibit more aggressive behavior, anxiety, and depressive symptoms than did the children whose mothers worked a typical daytime schedule (Dunifon et al., 2013). In another study, researchers found that mothers who worked more often at night (starting at 9:00 p.m. or later) spent less time with their adolescents, and that their adolescents had a lower-quality home environment (e.g., in terms of the quality of mother–child interactions, the cleanliness and safety of the home, and so on), which in turn predicted higher levels of adolescents’ risky behaviors. These effects were especially strong for boys in low-income families. However, similar negative effects were not found in the case of mothers who worked evening shifts that ended by midnight or who had other nonstandard work schedules (e.g., those with varying hours) that allowed them greater knowledge of their children’s whereabouts (Han, Miller, & Waldfogel, 2010).

There appear to be costs and benefits of maternal employment for low-income families, depending on the circumstances. Adolescents in single-parent, mother-headed families report feeling more positive emotions and higher self-esteem if their mothers are employed full time (Duckett & Richards, 1995), perhaps because maternal employment is critical for pulling mother-headed, poor families out of poverty (Harvey, 1999; Lichter & Lansdale, 1995). Nonetheless, there is also some evidence that unmarried mothers with poor-paying jobs may become less supportive of their children and provide a less stimulating home environment after they start working, compared with when they were at home full time (Menaghan & Parcel, 1995). This drop in supportiveness is no doubt linked to the fact that single mothers with low-paying jobs are particularly likely to be stressed, unhappy with their jobs, and unable to afford services to assist them with child rearing.

Maternal employment may have specific benefits for girls. Children of employed mothers are more likely than children of nonemployed mothers to reject the confining aspects of traditional gender roles, and they are more likely to believe that women are as competent as men (L. W. Hoffman, 1984, 1989). Children of employed mothers are also more likely to be exposed to egalitarian parental roles in the family, and this experience seems to affect girls’ feelings of effectiveness (L. W. Hoffman & Youngblade, 1999). In addition, compared with peers whose mothers are not employed, daughters of employed mothers tend to have higher aspirations (Gottfried et al., 2002) and, in African American, working-class families, are more likely to stay in school (Wolfer & Moen, 1996).

500

The impact that maternal employment—or the lack thereof—can have on children also depends in part on how the mother is affected by her employment status (Kalil & Ziol-Guest, 2005). For example, mothers who want to work but do not are sometimes depressed (Gove & Zeiss, 1987), whereas for those who want to work and do, employment can have a positive effect on their mood and sense of effectiveness (L. W. Hoffman & Youngblade, 1999), which would be expected to affect the quality of their parenting (Bugental & Johnston, 2000).

For many mothers, part-time work may be ideal. Recent research on mothers who were employed full-time, part-time, or not at all indicates that compared with unemployed mothers, mothers who worked part-time had fewer depressive symptoms and better health. And compared with mothers who worked full-time, mothers who worked part-time showed more sensitive parenting during the preschool years, were more involved in their children’s schooling and learning in general, and their children exhibited fewer externalizing problems (Brooks-Gunn et al., 2010; Buehler & O’Brien, 2011).

As already noted, a factor that is key to how maternal employment affects children’s development is the nature and quality of the day care children receive. But there, too, the effects vary as a function of the context and the individuals involved.

The Effects of Child Care

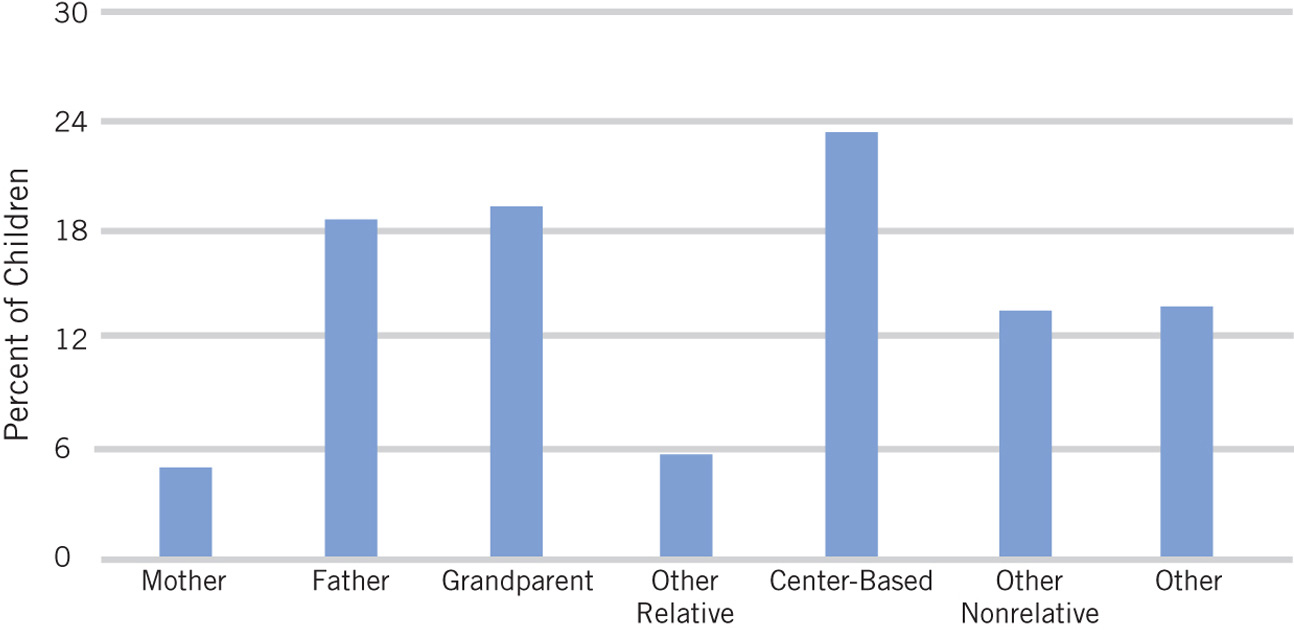

Because so many mothers work outside the home, a large number of infants and young children receive care on a regular basis from someone besides their parents. In the United States in 2010, 48% of children 4 years or younger with employed mothers were cared for primarily by a parent or another relative; nearly 24% were mostly in center-based child care; and 13.5% were cared for by a nonrelative in a home environment (e.g., babysitter, family day-care provider, nanny) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2013; see Figure 12.6).

In regard to the debate over potential risks and benefits of nonparental child care, some experts have argued that, especially for children from deprived backgrounds, group care, with its wide variety of activities, can provide greater cognitive stimulation than care at home (Consortium for Longitudinal Studies, 1983). Some have also suggested that children in group care learn important social skills through their interactions with peers (Clarke-Stewart, 1981; Volling & Feagans, 1995). Critics counter that enriched cognitive stimulation is provided only by high-quality child care and that much of the child care that is currently available does not provide as much stimulation as care by a parent at home does. Critics also point out that although children in child care may learn social skills from interactions with their peers, they also learn negative behaviors, such as aggression, because of the need to assert oneself in the group setting (J. E. Bates et al., 1994; Haskins, 1985).

501

Probably the greatest concern about child care initially was that it might undermine the early mother–child relationship (e.g., Belsky, 1986). For example, on the basis of attachment theory (see Chapter 11), it has been argued that young children who are frequently separated from their mothers are more likely to develop insecure attachments to their mothers than are children whose daily care is provided by their mothers. As you will now see, that concern is largely unwarranted.

Attachment and the Parent–Child Relationship

The issue of whether nonparental child care in the early years interferes with children’s attachment relationships to their parents has been examined in many studies. A variety of those involving infants and preschoolers show no evidence overall that children in child care are less securely attached than other children or that they display less positive behavior in interactions with their mothers (Erel, Oberman, & Yirmiya, 2000). Other research indicates that in a small minority of cases, extensive child care is associated with negative effects on attachment, but these cases tend to involve other care-related risk factors, such as frequent turnover in outside caregivers, a high ratio of infants per caregiver, and poor-quality care at home (M. E. Lamb, 1998; Sagi et al, 2002).

Similar findings have been shown in a major in-depth study funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) that has followed the development of approximately 1300 children in various child-care arrangements and in elementary school. This study, begun in 1991, includes families who are from 10 locations around the United States and who vary considerably in their economic status, ethnicity, and race. The study measures (1) characteristics of the families and the child-care setting, (2) children’s attachment to, and interactions with, their mothers, and (3) their social behavior, cognitive development, and health status.

502

A particularly important finding in this study is that how children fare in a nonmaternal care situation is much more strongly related to characteristics of the family—such as level of income, maternal education, maternal sensitivity, and the like—than to the nature of the child care itself. Moreover, any effects, positive or negative, that child care might have on development appear to be very limited in magnitude. Indeed, insecure attachments of a notable degree were predicted only when two conditions existed simultaneously—that is, (1) when the children experienced poor-quality child care, had 10 or more hours of child care per week, or had more than one child-care arrangement; and (2) when their mothers were not very sensitive or responsive to them (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997a).

When children were 24 and 36 months old, the quality of mother–child interaction was, to a slight degree, predicted by the number of hours in child care. Compared with mothers who did not use child care or who put their child in care for fewer hours, mothers of children who were in day care for longer hours tended to be less sensitive with their children, and their children tended to be less positive in interactions with them (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999). Even in these circumstances, the magnitudes of the effects were small.

Adjustment and Social Behavior

The possible effects of child care on children’s self-control, compliance, and social behavior have also been a focus of much concern and research. Here, the findings are mixed and sometimes depend on the specific mode of analysis (e.g., Crosby et al., 2010) and the country in which the research was conducted. A number of investigators have found that children who are in child care do not differ in problem behavior from those reared at home (Barnes et al., 2010; Erel et al., 2000; M. E. Lamb, 1998). Indeed, in two recent large studies in Norway, a country in which the quality of child care is uniformly high, researchers found little consistent relation between amount of time in child care and children’s externalizing problems, such as aggression and noncompliance, or social competence (Solheim et al., 2013; Zachrisson et al., 2013).

These findings are in notable contrast to those from the NICHD study in the United States, where the quality of child care is more variable. The NICHD study indicates that many hours a day in child care or a number of changes in caregivers in the first 2 years of life predicted lower social competence and more noncompliance with adults at age 2 (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1998a). At 4½ years of age, children in extensive child care were viewed by care providers (but not by mothers) as exhibiting more problem behaviors, such as aggression, noncompliance, and anxiety/depression (NICHD Early Child Care Network, 2006). The relation between more hours in center care and teacher-reported externalizing problems (e.g., aggression, defiance) was also found in the elementary school years but generally was not significant by 6th grade (Belsky et al., 2007). However, more hours of nonrelative care predicted greater risk taking and impulsivity at age 15 (Vandell et al., 2010).

Significantly, the finding that greater time in child care is related to increased risk for adjustment problems appears not to apply to children from very low-income, high-risk families (Côté et al., 2008). In fact, longer time in child care has been found to be positively related to the better adjustment of such children, unless the quality of care is very poor (Votruba-Drzal, Coley, & Chase-Lansdale, 2004). Similarly, in a large study of children from high-risk families in Canada, physical aggression was less common among children who were in group day care than among those who were looked after by their own families (Borge et al., 2004). High-quality child care that involves programs designed to promote children’s later success at school may be especially beneficial for disadvantaged children. As in the case of Project Head Start, discussed in Chapter 8, children who experience these programs show improvements in their social competence and declines in conduct problems (Keys et al., 2013; M. E. Lamb, 1998; Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001; Webster-Stratton, 1998; Zhai, Brooks-Gunn, & Waldfogel, 2011).

503

Thus, it appears that most children in child care never develop significant behavior problems, but for some, the risk that they will develop such problems increases with an increase in hours spent in child care, especially center care (R. L. Coley et al., 2013). In the NICHD study, this risk was higher when children spent many hours with a large group of peers and in low-quality child care (the overall risk was modest and was not due to the characteristics of children who are put in child care for longer hours) (McCartney et al., 2010). More generally, higher-quality child care in the NICHD study was related to fewer externalizing problems in the early years (McCartney et al., 2010) and at age 15 (Vandell et al., 2010)—a relation primarily seen in children and adolescents who were prone to negative emotion (Belsky & Pluess, 2012; Pluess & Belsky, 2010) or who had a particular variant of gene DRD4, which, as discussed in Chapter 11, is associated with being susceptible to the effects of the environment (Belsky & Pluess, 2013).

In addition, it must be remembered that the background characteristics (e.g., family income, parental education, parental personality) of children who are in day care for long hours likely differ in a variety of ways from those of children in day care for fewer hours. Therefore, cause-and-effect relations cannot be assumed, even when the effects of some of these factors are taken into account (Bolger & Scarr, 1995; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1997b). Furthermore, the number of hours spent in child care is less relevant than the quality of child care provided: no matter what their SES background, children in high-quality child-care programs tend to be well adjusted and to develop social competencies (Love et al., 2003; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2003; Votruba-Drzal et al., 2004).

As noted earlier, another factor related to the effects of child care on children’s adjustment is the number of changes in the child care provided to children. In the NICHD study, increases in the number of nonparental child-care arrangements were associated with increases in children’s problem behaviors and lower levels of positive behavior such as compliance and constructive expression of emotion (Morrissey, 2009). Instability of child care was also related to poorer adjustment in an Australian study (Love et al., 2003).

Cognitive and Language Development

The possible effects of child care on children’s cognitive and language performance are of particular concern to educators as well as to parents. Research suggests that high-quality child care can have a modest, positive effect on these aspects of children’s functioning (Keys et al., 2013), although the effects sometimes weaken over time (Côté et al., 2013). The NICHD study found that, overall, the number of hours in child care did not correlate with cognitive or language development when demographic variables such as family income were taken into account. However, higher-quality child care that included specific efforts to stimulate children’s language development was linked to better cognitive and language development in the first 3 years of life (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2000b). Children in higher-quality child care (especially center care) scored higher on tests of preacademic cognitive skills, language abilities, and attention than did those in lower-quality care (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002, 2006; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network & Duncan, 2003). Higher- quality care also predicted mothers’ greater involvement in their children’s schooling when the children were in kindergarten. This would be expected to foster children’s school performance (Crosnoe et al., 2012); promote higher vocabulary (but not reading and math) scores in elementary school (Belsky et al., 2007); and cultivate higher cognitive and academic achievement at age 15 (Vandell et al., 2010). Moreover, for children in high-quality care, low income was less likely to predict underachievement at 4½ to 11 years of age (Dearing et al., 2009).

504

Other research also suggests that child care may have positive effects on cognition and that these effects are larger for higher-quality centers (Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001). For instance, in Sweden and the United States, a number of researchers have found that children enrolled in out-of-home child care perform better on cognitive tasks, even in elementary school (Erel et al., 2000; M. E. Lamb, 1998). In addition, children from low-income families who spend long hours in child care, compared with those who spend fewer hours, tend to show increases in quantitative skills (Votruba-Drzal et al., 2004). It is likely that child care, unless it is of low quality, provides greater cognitive stimulation than is available in some low-income homes.

Quality of Child Care

It is not surprising that the quality of child care children receive outside the home is related to some aspects of their development. Unfortunately, most child-care centers in the United States do not meet the recommended minimal standards established by such organizations as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Public Health Association. These minimum standards include:

A child-to-caregiver ratio of 3:1 for children aged 12 months or less; 4:1 for 13- to 35-month-olds; 7:1 for 3-year-olds; and 8:1 for 4-and 5-year-olds

A child-to-caregiver ratio of 3:1 for children aged 12 months or less; 4:1 for 13- to 35-month-olds; 7:1 for 3-year-olds; and 8:1 for 4-and 5-year-olds Maximum group sizes of 6 for 12-months-olds and younger; 8 for 13- to 35-month-olds; 14 for 3-year-olds; and 16 for 4- and 5-year-olds

Maximum group sizes of 6 for 12-months-olds and younger; 8 for 13- to 35-month-olds; 14 for 3-year-olds; and 16 for 4- and 5-year-olds Formal training for caregivers, with lead teachers having (1) a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education, school-age care, child development, social work, nursing, or other child-related field, or an associate’s degree in early childhood education and currently working toward a bachelor’s degree; (2) at least one year of on-the-job training in providing a nurturing environment and meeting children’s out-of-home needs (American Academy of Pediatrics et al., 2011).

Formal training for caregivers, with lead teachers having (1) a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education, school-age care, child development, social work, nursing, or other child-related field, or an associate’s degree in early childhood education and currently working toward a bachelor’s degree; (2) at least one year of on-the-job training in providing a nurturing environment and meeting children’s out-of-home needs (American Academy of Pediatrics et al., 2011).

For child-care facilities in homes, the recommended minimum standards are more stringent; for example, the child–caregiver ratios are 2:1 for children 23 months and younger, 3:1 for 24- to 35-month-olds, 7:1 for 4-year-olds, and 8:1 for 5-year-olds, with maximum group size of 6, 8, 12, and 12 for these age groups, respectively.

In the NICHD study, children in a form of day care that met more of these guidelines tended to score higher on tests of language comprehension and readiness for school, and they had fewer behavior problems at age 36 months. The more standards that were met, the better the children performed at 3 years of age (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1998b). (See Table 12.1 for quality standards set by an early-education association for quality child care.) Quality was generally highest in nonprofit centers that were not religiously affiliated; intermediate in nonprofit religiously affiliated centers and in for-profit independent centers; and lowest in for-profit chains (Sosinsky, Lord, & Zigler, 2007).

505

506

review:

The bulk of recent research on maternal employment indicates that it often benefits children and mothers and that it has few negative effects on children if they are in child care of acceptable quality and are supervised and monitored. Unfortunately, however, in low-income families, especially those headed by a single parent, adequate child care and supervision may not always be possible.

Because so many mothers work, a large proportion of children receive some care from adults other than their parents. Recent research on child care indicates that, on the whole, nonmaternal care has small, if any, effect on the quality of the mother–child relationship. Children who spend long hours in centers tend to exhibit more aggressive behavior at schools, but the effects are modest and likely are nonsignificant for high-quality child care. High-quality care does appear to have some modest benefits for cognitive development and especially language development. Whether child care has positive or negative effects on children’s functioning probably depends on the characteristics of the child, the number of hours in care, the quality of parenting at home, and the quality of the care situation.