Theme 3: Development Is Both Continuous and Discontinuous

Long before there was a scientific discipline of child development, philosophers and others interested in human nature argued about whether development is continuous or discontinuous. Current disputes between those who believe that development is continuous, such as social learning theorists, and those who believe it is discontinuous, such as stage theorists, thus have a long history. There is good reason why both positions have endured so long: each captures important truths about development, and neither captures the whole truth. Two particularly important issues in this longstanding debate involve continuity/discontinuity of individual differences and continuity/discontinuity of the standard course of development with age.

Continuity/Discontinuity of Individual Differences

One sense of continuity/discontinuity involves stability of individual differences over time. The basic question is whether children who initially are higher or lower than most peers in some quality continue to be higher or lower in that quality years later. It turns out that many individual differences in psychological properties are moderately stable over the course of development, but the stability is always far from 100%.

Consider the development of intelligence. Some stability is present from infancy onward. For example, the faster that infants habituate to repeated presentation of the same display, the higher their IQ scores tend to be 10 or more years later. Infants’ patterns of electrical brain activity also are related to their speed of processing and attention regulation more than 10 years later. The amount of stability increases with age. IQ scores show some stability from age 3 to age 13, considerable stability from age 5 to age 15, and substantial stability from age 8 to age 18.

Even in older children, however, IQ scores vary from occasion to occasion. For example, when the same children take IQ tests at ages 8 and 17, the two scores differ on average by 9 points. Part of this variability reflects random fluctuations in how sharp the person is on the day of testing and in the person’s knowledge of the particular questions on each test. Another part of the variability reflects the fact that even if two children start out with equal intelligence, one may show greater intellectual growth over time.

Individual differences in social and personality characteristics also show some continuity over time. Shy toddlers tend to grow into shy children, fearful toddlers into fearful children, aggressive children into aggressive adolescents, generous children into generous adults, and so on. The continuity also carries over into situations quite different from any that the children faced at the earlier time; for example, secure attachments in infancy predict positive romantic relationships in adolescence.

Although there is some continuity of individual differences in social, emotional, and personality development, the degree of continuity is generally lower than in intellectual development. For example, whereas children who are high in reading and math achievement in 5th grade generally remain so in 7th grade, children who are popular in 5th grade may or may not be popular in 7th grade. In addition, aspects of temperament such as fearfulness and shyness often change considerably over the course of early and middle childhood.

Regardless of whether the focus is on intellectual, social, or emotional development, the stability of individual differences is influenced by the stability of the environment. For instance, an infant’s attachment to his or her mother correlates positively with the infant’s long-term security, but the correlation is higher if the home environment stays consistent than if serious disruptions occur. Similarly, IQ scores are more stable if the home environment remains stable. Thus, continuities in individual differences reflect continuities in children’s environments as well as in their genes.

646

Continuity/Discontinuity of Overall Development: The Question of Stages

Many of the most prominent theories of development divide childhood and adolescence into a small number of discrete stages. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, Freud’s theory of psychosexual development, Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, and Kohlberg’s theory of moral development all describe development in this way. The enduring popularity of these stage approaches is easy to understand: they simplify the enormously complicated process of development by dividing it into a few distinct periods; they point to important characteristics of behavior during each period; and they impart an overall sense of coherence to the developmental process.

Although stage theories differ in their particulars, they share four key assumptions: (1) development progresses through a series of qualitatively distinct stages; (2) when children are in a given stage, a fairly broad range of their thinking and behavior exhibits the features characteristic of that stage; (3) the stages occur in the same order for all children; and (4) transitions between stages occur quickly.

Development turns out to be considerably less tidy than stage approaches imply, however. Children who exhibit preoperational reasoning on some tasks often exhibit concrete operational reasoning on others; children who reason in a preconventional way about some moral dilemmas often reason in a conventional way about others; and so on. Rarely is a sudden change evident across a broad range of tasks.

In addition, developmental processes often show a great deal of continuity. Throughout childhood and adolescence, there are continuous increases in the ability to regulate emotions, make friends, take other people’s perspectives, remember events, solve problems, and engage in many other activities.

This does not mean that there are no sudden jumps. When we consider specific tasks and processes, rather than broad domains, we see many discontinuities. Three-month-olds move from having almost no binocular depth perception to having adultlike levels within a week or two. Before age 7 months, infants rarely fear strangers, but thereafter, wariness of them develops quickly. Many toddlers move in a single day from being unable to walk without support to walking unsupported for a number of steps. After acquiring about one word per week between ages 12 and 18 months, toddlers undergo a vocabulary explosion, in which the number of words they know and use expands rapidly for years thereafter. Thus, although broad domains, such as intelligence and personality, rarely show discontinuous changes, specific aspects of development fairly often do.

Whether development appears to be continuous or discontinuous often varies with whether the focus is on behavior or on underlying processes. Behaviors that emerge or disappear quite suddenly may reflect continuous underlying processes. Recall the case of infants’ stepping reflex. For the first two months after birth, if infants are supported in an upright position with their feet touching the ground, they will first lift one leg and then the other in a pattern similar to walking. At around age 2 months, this reflex suddenly disappears. Underlying the abrupt change in behavior, however, are gradual changes in two dimensions that underlie the behavioral change—weight and leg strength. As babies grow, their gain in weight temporarily outstrips their gain in leg strength, and they become unable to lift their legs without help. Thus, when babies who have stopped exhibiting the stepping reflex are supported in a tank of water, making it easier for them to lift their legs, the stepping reflex reappears.

647

Whether development appears continuous or discontinuous also depends on the time scale being considered. Recall that when a child’s height was measured every 6 months from birth to 18 years, the growth looked continuous (see Figure 1.3). When height was measured daily, however, development looked discontinuous, with occasional “growth days” sprinkled among numerous days without growth.

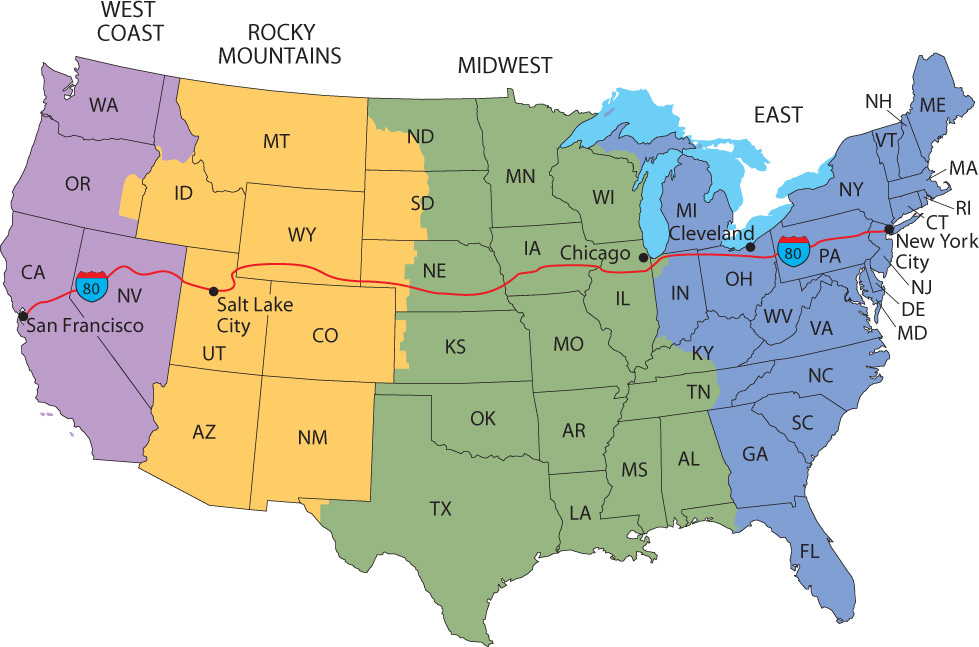

One useful framework for thinking about developmental continuities and discontinuities is to envision development as a road trip through the United States, from New York City to San Francisco. In one sense, the drive is a continuous progression westward along Interstate 80. In another sense, the drive starts in the East and then proceeds (in an invariant order, without the possibility of skipping a region) through the Midwest and the Rocky Mountains before reaching its end point in California. The East includes the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachians, and it tends to be hilly, cloudy, and green; the Midwest tends to be flatter, dryer, and sunnier; the Mountain States are dryer and sunnier still, with extensive mountainous areas; and most of California is dry and sunny, with both extensive flat and extensive mountainous areas. The differences between regions in climate, color, and topography are large and real, but the boundaries between them are arbitrary. Is Ohio the westernmost eastern state or the easternmost midwestern state? Is eastern Colorado part of the Midwest or part of the Rocky Mountain region?

The continuities and discontinuities in development are a lot like those on the road trip. Consider children’s conceptions of the self. At one level of analysis, the development of the self is continuous. Over the course of development, children (and adults) understand more and more about themselves. At another level of analysis, milestones characterize each period of development. During infancy, children come to distinguish between themselves and other people, but they rarely if ever see themselves from another person’s perspective. During the toddler period, children increasingly view themselves as others might, which allows them to feel such emotions as shame and embarrassment. During the preschool period, children realize that certain of their personal characteristics, such as their gender, are fundamental and permanent, and they use this knowledge to guide their behavior. During the elementary school years, children increasingly think of themselves in terms of their competencies relative to other children’s (intelligence, athletic skill, popularity, and so forth). During adolescence, they come to recognize how differently they themselves act in different situations.

648

Thus, any statement about when a given competency emerges is somewhat arbitrary, much like a statement about where a geographic region begins. Nonetheless, identifying the milestones helps us understand roughly where we are on the map.