Theme 5: The Sociocultural Context Shapes Development

Children develop within a personal context of other people: families, friends, neighbors, teachers, and classmates. They also develop within an impersonal context of historical, economic, technological, and political forces, as well as societal beliefs, attitudes, and values. The impersonal context is as important as the personal one in shaping development. There is little reason to think that parents in developed societies in the twenty-first century love their children more than parents of the past did. Yet their children die less often, get sick less often, eat a more nutritious diet, and receive more formal schooling than did children from even the wealthiest families of 100 or 200 years ago. Thus, when and where children grow up profoundly influences their lives.

Growing Up in Societies with Different Practices and Values

Values and practices that people within a society take for granted as “natural” often vary substantially among societies. These variations considerably influence the rate and form of development. Throughout the book, you encountered examples of this in every aspect of development, including in domains that are commonly thought of as governed entirely by maturation. For example, people often assume that the timing of walking and other motor skills in infancy is determined solely by biology, but babies who grow up in African tribes that strongly encourage infants’ motor development tend to walk and reach other motor milestones earlier than do infants in the United States. Similarly, infants in societies where babies sleep with their mothers for several years exhibit less fear at bedtime than do children in the United States, where babies rarely sleep with their mothers, or even in the same room with them, for more than 6 months.

654

Emotional reactions provide another example of how cultural practices and values influence behavior, even when we might not expect them to do so. Infants in all societies that have been studied show the same attachment patterns, but the frequency of occurrence of each pattern varies with the values of the society. Relative to babies in the United States, for instance, Japanese babies who are placed in the Strange Situation more often become very upset, showing the insecure-resistant attachment pattern. These differences in attachment patterns appear to be due to differing cultural values and practices. Japanese mothers traditionally encourage dependence in children and rarely leave their babies alone, which may lead the babies to become especially upset when they are left alone in the Strange Situation. In contrast, U.S. parents emphasize independence to a greater degree and more often leave babies alone in a room or with other people.

Cultural influences such as these continue well beyond infancy. Japanese culture, for example, places a higher value on hiding negative emotions, especially anger, than does American culture, and Japanese mothers discourage their children from expressing negative emotions. Quite likely because of these cultural influences, Japanese preschoolers and school-age children less often express anger and other negative emotions than do U.S. peers. Similarly, child rearing in rural Mexican villages emphasizes cooperation and caring about others, and children raised in these villages are more likely to share their possessions than are children from Mexican cities or the United States.

Culture influences not only parents’ actions but also children’s interpretations of those actions. For example, Chinese American mothers use a great deal of scolding and guilt to control their children. In the broader U.S. population, use of this disciplinary approach is associated with negative outcomes, but the association is not present among Chinese American children. The differing effectiveness of the disciplinary approaches may reflect children’s interpretations of their parents’ behavior. If children believe that scolding or authoritarian parenting is in their best interest, the behaviors can be effective. However, if children see such disciplinary approaches as reflecting negative parental feelings toward them, the discipline tends to be ineffective or harmful.

Sociocultural differences exert a similar influence on cognitive development. They help determine which skills and knowledge children acquire—for instance, whether children learn to operate abacuses, iPads, or both. They also influence how well children learn skills that everyone acquires to some degree; for example, Australian Aboriginal children, whose lives will eventually depend on their ability to trek through the desert to distant oases, develop spatial skills superior to those of urban Australian children. Finally, cultural values influence the educational system, which in turn influences what and how deeply children learn. For example, students in community-of-learners classrooms learn about fewer scientific topics than do children in traditional classrooms, but they learn about them in greater depth.

655

Growing Up in Different Times and Places

When and where children grow up profoundly influences their development. As noted earlier, in modern societies, children’s lives are greatly improved over what they were in the past, in terms of health, nutrition, shelter, and so on. Not all of the changes in modern societies have promoted children’s well-being, however. For example, in North America and Europe, far more children grow up with divorced parents than in the past, and these children are at risk for many problems. On average, they are more prone to sadness and depression, have lower self-esteem, do less well in school, and are less socially competent than peers who live in intact families. Although most children from divorced families do not have serious problems, a minority do: engaging in delinquent activities, dropping out of school, and having children out of wedlock all are more common among children whose parents are divorced.

Other historical changes may result in children’s lives being different, but neither better nor worse. The great expansion of child care outside the home represents one such case. In the United States, about half of infants and three-fourths of 4-year-olds currently receive child care outside their homes—five times the rates in 1965. As this change was occurring, many people feared that such care would weaken attachment between babies and mothers. Others expressed hopes that such care would greatly stimulate cognitive development, especially of children from impoverished backgrounds, because of the greater opportunities for interaction with other children and adults. In fact, the data indicate that neither the fears nor the hopes were justified. In almost all respects, children who receive care outside the home tend to develop similarly, both emotionally and cognitively, to those who do not.

More generally, the same cultural or technological change can bring either positive or negative effects, depending on who the child is and how the innovation is used. For instance, the Internet can be used to communicate with friends, which tends to strengthen friendships, but it can also be used for cyberbullying. Playing certain Internet games stimulates development of attention, but very high frequency of playing Internet games can harm the quality of friendships. Thus, in terms of health, comfort, and material well-being, children growing up today in modern societies are, on the whole, better off than those who grew up in the past—but in other ways, the picture is more mixed.

Growing Up in Different Circumstances Within a Society

Even among children growing up at the same time in the same society, differences in economic circumstances, family relationships, and peer groups lead to large differences in children’s lives.

Economic Influences

In every society, the economic circumstances of a child’s family considerably influence the child’s life. However, the degree of economic inequality within each society influences just how large a difference the economic circumstances make. In societies with large income inequalities, such as the United States, poor children’s academic achievement is far lower than that of children from wealthier families. In societies with smaller inequalities, such as Japan and Sweden, children from affluent families also do better academically than children from poorer families, but the differences are smaller.

656

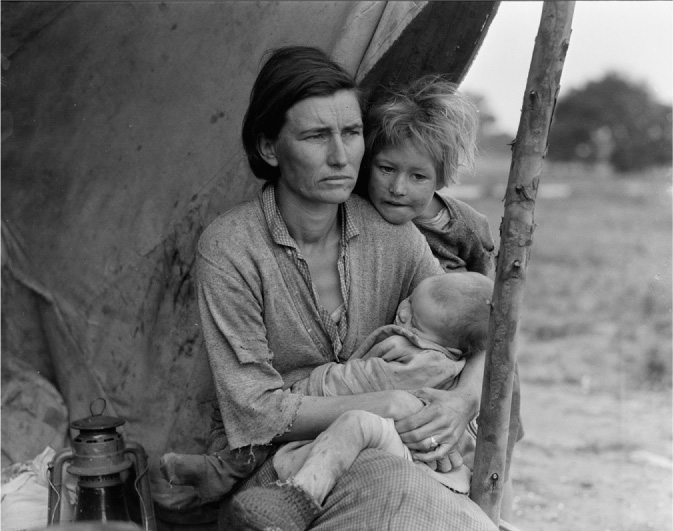

It is not just academic achievement that is influenced by economic circumstances; all aspects of development are. Infants from impoverished families more often are insecurely attached to their mothers. Children and adolescents from impoverished families more often are rejected as friends and more often are lonely. Illegal substance use, crime, and depression also are more common among poor adolescents than among peers from wealthier backgrounds.

These negative outcomes are unsurprising, given the many disadvantages that poor children face. Relative to children who grow up in more affluent environments, poor children more often live in dangerous neighborhoods; grow up in homes with one or no biological parents; attend inferior day-care centers and schools; and have few books, magazines, and other intellectually stimulating material in their homes. The cumulative burden of these disadvantages, rather than any one of them, poses the greatest obstacle to successful development.

Influences of Family and Peers

Families and peer groups vary considerably in ways other than income, and many of these differences also have a substantial influence on development. In some families, regardless of income, parents are sensitive to babies’ needs and form close attachments with them; in others, this does not occur. In some families, again regardless of income, parents read to their children each night, thus helping the children to learn to read; in others, this practice does not occur.

The influence of friends, other peers, teachers, and other adults varies in as many ways as that of families. Friends, for example, can provide companionship and feedback, contribute to self-esteem, and serve as a buffer against stress; during adolescence, they can be particularly important sources of sympathy and support. On the other hand, friends can also have a negative influence, drawing children and adolescents into reckless and aggressive behavior, including crime, drinking, and drug use. Thus, personal relationships, like economic circumstances, culture, and technology, definitely influence development, but the effects of these influences vary with the particulars.