Theme 6: Individual Differences

Children differ on a huge number of dimensions—demographic characteristics (gender, race, ethnicity, SES), psychological characteristics (intellect, personality, artistic ability), experiences (where they grow up; whether their parents are divorced; whether they participate in plays, bands, or organized sports), and so on. How can we tell which individual differences are the crucial ones for understanding children and predicting their futures?

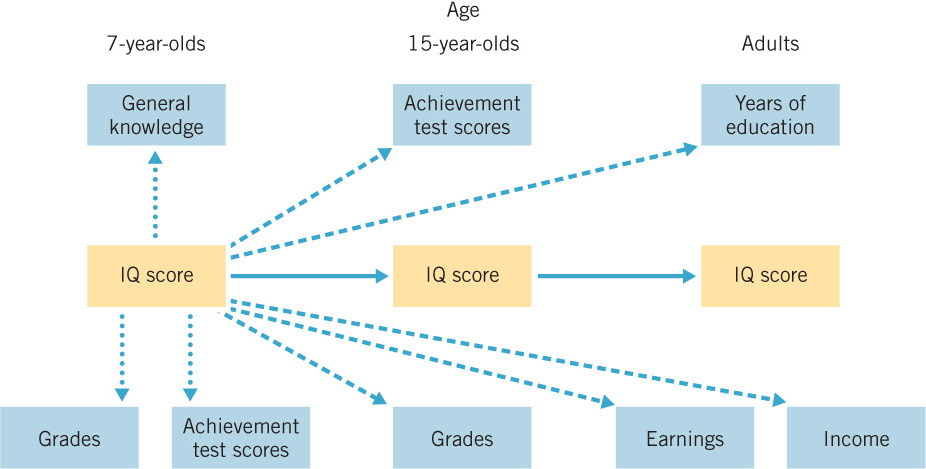

As illustrated in Figure 16.1, three characteristics—breadth of related characteristics, stability over time, and predictive value—are crucial in determining the importance of any dimension of individual differences. First, as shown by the dotted vertical arrows, children’s status on the most important dimensions is associated with their status at that time on other important dimensions. Thus, one reason why intelligence is considered a central individual difference is that the higher a child’s IQ at a given age, the higher the child’s grades, achievement test scores, and general knowledge tend to be at the same time (the dotted arrows in Figure 16.1). A second key characteristic is stability over time (the solid arrows in Figure 16.1). A dimension of individual differences is of greater interest if the higher or lower that children score on it early in development, the higher or lower they are likely to score on it later. Thus, another reason for interest in IQ is that children with high (or low) IQs usually grow into adults with high (or low) IQs. A third characteristic of major dimensions of individual differences is that a child’s status on the dimension predicts outcomes on other important characteristics in the future (the dashed arrows in Figure 16.1). Thus, a third reason for interest in IQ scores is that a person’s IQ during middle childhood and adolescence predicts that person’s later earnings, occupational status, and years of education.

657

These three characteristics make clear why demographic variables such as gender, race, ethnicity, and SES are studied so often. Consider gender, for example. Gender differences are related to a wide variety of other differences. Boys tend to be larger, stronger, more physically active, and more aggressive; to play in larger groups; to be better at some forms of spatial thinking; and more often to have ADHD and math or reading disabilities. Girls tend to be more verbal, quicker to perceive emotions, better at writing, and more likely to express sympathy and empathy for people in distress. Being male or female obviously is also stable over time. Finally, being male or female predicts future individual differences. If a newborn is female, it is likely that, compared with males, she will be more self-revealing with friends, more vulnerable to depression, more inclined to prosocial behavior, and more disposed to using relational aggression.

We next consider the extent to which several other variables show these three key characteristics of major individual differences.

Breadth of Individual Differences at a Given Time

Individual differences are not randomly distributed. Children who are high on one dimension also tend to be high on other, conceptually related dimensions. Thus, children who do well on one measure of intellect—language, memory, conceptual understanding, problem solving, reading, or mathematics—tend to do well on others. Similarly, children who do well on one measure of social or emotional functioning—relations with parents, relations with peers, relations with teachers, self-esteem, prosocial behavior, and lack of aggression and lying—also tend to do well on others. Sometimes, as with the relation between intelligence and school achievement, the connections are very strong. More often, the relations are moderate. Thus, although children who get along well with their parents also tend to get along well with peers, there are many exceptions.

658

Beyond intelligence and gender, two other crucial dimensions of individual differences are attachment and self-esteem. Compared with their insecurely attached peers, toddlers who are securely attached to their mother tend to be more enthusiastic and positive about solving problems with her, to comply more often with her directives, and to obey her requests even when she isn’t present. Such children also tend to get along better with other toddlers and to be more sociable and more socially competent. Similarly, children and adolescents who are high in self-esteem also tend to be strong on many other dimensions of social and emotional functioning. They tend to be generally hopeful and popular, to have many friends, and to have good academic and self-regulation skills. In contrast, those with low self-esteem tend to feel hopeless and to be prone to problems such as depression, aggression, and social withdrawal.

Stability Over Time

Many individual differences show moderate stability over time. For instance, people who have easy temperaments during infancy tend to continue to have easy temperaments in middle and later childhood. Similarly, elementary school children with ADHD, reading disabilities, or mathematics disabilities usually have lifelong difficulties in those areas.

The reasons for such stability of psychological characteristics are to be found in the stability of both genes and environment. A child’s genotype remains identical over the course of development (though particular genes switch on and off at different times). Most children’s environments remain fairly stable as well. Families that are middle-class when a child is born tend to remain middle-class; families that value education when the child is born usually continue to value education; families that are sensitive and supportive generally remain that way; and so on. Major changes, such as divorce and unemployment, do occur, and they affect children’s happiness, self-esteem, and other characteristics. Nonetheless, the stability of children’s environments, like the stability of their genes, contributes to the stability over time of their psychological functioning.

Predicting Future Individual Differences on Other Dimensions

Individual differences on some dimensions are related not only to future status on that dimension but also to future status on other dimensions. For example, children who are securely attached as infants tend as toddlers and preschoolers to have more social ties to their peers than do children who were insecurely attached as infants. When they reach school age, they tend to understand other children’s emotions relatively well and to be relatively skilled in resolving conflicts. When they reach adolescence and adulthood, they tend to form close attachments with romantic partners. All of these outcomes are consistent with the view that secure early attachment provides a working model that influences subsequent relationships with other people.

659

As with stability over time of a single dimension, the relative stability of most children’s environments contributes to these long-term continuities of psychological functioning. If children’s environments change in important ways, the typical continuities may be disrupted accordingly. Thus, stressful events such as divorce reduce the likelihood that children who were securely attached during infancy will continue to show the positive relations with peers usually associated with secure attachment.

Determinants of Individual Differences

Individual differences, like all aspects of development, are ultimately attributable to the interaction of children’s genes and the environments they encounter.

Genetics

For a number of important characteristics—including IQ, prosocial behavior, and empathy—about 50% of the differences among individuals in a given population are attributable to differences in genetic inheritance. The degree of genetic influence on individual differences tends to increase over the course of development. For example, correlations between the IQs of adopted children and their biological parents steadily increase over the course of childhood and adolescence, even if the children never meet or have any contact with their biological parents. One reason for this is that many genes related to intellectual functioning do not exercise their effects until late childhood or adolescence. Another reason is that over the course of development, children become increasingly free to choose environments that are in accord with their genetic predispositions.

Experience

Individual differences reflect children’s experiences as well as their genes. Consider just one major environmental influence: the parents who raise the children. The more speech that parents address to their toddlers, the more rapidly the toddlers recognize familiar words and learn new ones. The more that parents aim their scaffolding at, but not beyond, the upper end of their children’s capabilities, the greater the improvement in their children’s problem solving. The more stimulating and responsive the home intellectual environment, the higher children’s IQ tends to be.

Parents exert at least as large an influence on their children’s social and emotional development as on their intellectual development. For example, the likelihood that children will adopt their parents’ standards and values appears to be influenced by the type of discipline their parents use with them. Similarly, parents influence their children’s willingness to share, especially if they discuss the reasons for sharing with their children and have good relationships with them.

The effect of different types of parenting, like the effects of children’s other experiences, depends on the child. One example of this involves the development of conscience. For fearful children, the key factor determining whether the child internalizes the parents’ moral values is gentle discipline. Fearful children may become so anxious in the face of rigorous discipline that they cannot focus on the moral values that the parents are trying to instill. For fearless children, on the other hand, the key factor is a positive relationship with one’s parents. Such fearless children often do not respond to gentle discipline; they tend to internalize the parents’ values only if they feel close to them. As an old adage states, “It’s a wise parent who knows his child.”

660